'Just Leave Me Alone': Social Isolation and Civic Disengagement for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defence Strategic Communications

Defence Strategic Communications | Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DEFENCE STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS DEFENCE STRATEGIC 12 Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DEFENCE STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS The official journal of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence AUTUMN 2018 The Acoustic World of Influence: How Musicology Illuminates Strategic Communications Hostile Gatekeeping: the Strategy of Engaging With Journalists in Extremism Reporting The ‘Fake News’ Label and Politicisation of Malaysia’s Elections Brand Putin: an Analysis of Vladimir Putin’s Projected Images What Does it Mean for a Communication to be Trusted? Strategic Communications at the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics: a Groundwork Study ISSN: 2500-9486 DOI: 10.30966/2018.RIGA.5. Defence Strategic Communications | Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DOI 10.30966/2018.RIGA.5.5 WHAT DOES IT MEAN 171 FOR A COMMUNICATION TO BE TRUSTED? Francesca Granelli Abstract Despite following best practice, most governments fail in their strategic communications. There is a missing ‘X’ factor: trust. This offers a quick win to strategic communicators, provided they understand what the phenomenon involves. Moreover, it allows practitioners to avoid the risk of citizens feeling betrayed when their government fails to deliver. Keywords: trust, communications, impersonal trust, distrust, reliance, co-operation, strategic communications About the author Dr Francesca Granelli is a Teaching Fellow at King’s College London, where her research focuses on trust. Her forthcoming book is Trust, Politics and Revolution: A European History. Defence Strategic Communications | Volume 5 | Autumn 2018 DOI 10.30966/2018.RIGA.5.5 172 Introduction Governments, politicians, and commentators are worried. The ‘crisis of trust’ is now a common refrain, which draws upon a mountain of apparent evidence.1 Edelman’s Trust Barometer, for instance, points to declining levels of trust in governments, NGOs, businesses, and the media across most countries each year. -

An Analysis of Low-Income Black Students and Educational Outcomes

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 What's "Black" Got to Do With It: An Analysis of Low-Income Black Students and Educational Outcomes Derrick E. Griffith Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/568 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] WHAT’S “BLACK” GOT TO DO WITH IT? AN ANALYSIS OF LOW-INCOME BLACK STUDENTS AND EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES by DERRICK EUGENE GRIFFITH A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Urban Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York (2015) © 2015 Derrick E. Griffith All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the graduate Faculty in Urban Education in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Juan Battle ________________________ _________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Anthony Picciano _________________________ _________________________ Date Executive Officer Anthony Picciano Nicholas Michelli Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT WHAT’S “BLACK” GOT TO DO WITH IT? AN ANALYSIS OF LOW-INCOME BLACK STUDENTS AND EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES by Derrick Eugene Griffith Adviser: Professor Juan Battle Well-known social scientist William Wilson notes the Black underclass is particularly at risk of developing behaviors and attitudes that promote educational and social isolation. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

A Phenomenological Research on Bajo Tribe's Social Life in Bone

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 2, Ver. 3 (February. 2018) PP 86-91 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A Disadvantaged Tribe in Bajoe Village, Bone Regency: A Phenomenological Research on Bajo Tribe’s Social Life in Bone Regency, South Sulawesi Andi Djalante, Andi Agustang; Suradi Tahmir, Jumadi Sahabuddin, Department of Sociology, Universitas Negeri Makassar Indonesia Abstract: The aims of this research are: (1) to reveal the dimensions of life within Bajo Tribe at Bajoe Village, Bone Regency; (2) to reveal the dimensions of disadvantaged social life within Bajo tribe at Bajoe Village, Bone Regency; (3) to find the right solution for changing the condition of the disadvantaged Bajo Tribe. The approach used in this research is qualitative method, specifically a phenomenological research on nine informants taken by purposive sampling. All data obtained through in-depth interview and observation are then analyzed inductively. The research findings include: (1) the discovery of real disadvantaged condition within the life of Bajo Tribe concerning the fulfillment of daily needs such as: the discrepancy within the expectation achievement and the shifting of social order and culture; (2) the discovery of each pattern’s relation and ways of thinking in Bajo Tribe which controlled by the custom; (3) the repairment effort of theoretical solution against two conditions, the first is controlling the social consciousness of Bajo Tribe toward the tendency in current survival, the second is how to enhance Bajo Tribe with active participation and put every activity on rational choice. The theoretical solution in the first condition is dealt with the theory of awareness control by Herbert Blumer, while the second condition is dealt with the theory of rational choice by James Samuel Coleman. -

L'équilibre Général Comme Savoir (De Walras À Nos Jours)

Action Concertée Incitative (ACI) du CNRS Programme interdisciplinaire « Histoire des Savoirs » Projet de recherche « L’équilibre général comme savoir : de Walras à nos jours » (nom administratif : hds-lenfant.jean-sébastien) Date de finalisation : 17 mai 2004 Auteurs : Jean-Sébastien Lenfant (Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne) et Jérôme Lallement (Université Paris V) L’équilibre général comme savoir (de Walras à nos jours) Jérôme Lallement (GRESE, université Paris V) Jean-Sébastien Lenfant (GRESE, université Paris 1) Sommaire : Prologue Maquette 1. Matériaux sur le savoir et les savoirs 2. De l’objet “ équilibre général ” 3. L’équilibre général comme savoir : questions de méthode 4. Thèmes de recherche 5. Références bibliographiques Prologue Oslo, vers la fin du mois de juillet 1905. Les cinq membres du comité pour le prix Nobel de la paix reçoivent un courrier signé par trois professeurs des Facultés de Droit et des Lettres de l’Université de Lausanne. “ Messieurs, En vertu du droit que nous confère libéralement l’article 1 (nos. 5 et 6) des dispositions provisoires par vous arrêtées, nous nous permettons de vous présenter comme candidat pour le prix Nobel de la paix, M. Léon Walras, professeur honoraire d’économie politique à l’Université de Lausanne, en raison de son ouvrage en 3 volumes intitulés respectivement : Eléments d’économie politique pure ou Théorie de la richesse sociale. 4ème édition 1900 ; Etudes d’économie sociale (Théorie de la répartition de la richesse sociale). 1896 ; Etudes d’économie politique appliquée (Théorie de la production de la richesse sociale). 1898. ” (Jaffé, 1965, vol.3, lettre 1595, 270-271) Et les trois professeurs d’accompagner leur proposition d’un texte de Walras. -

The Rise and Fall of the United Teachers of New Orleans

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE UNITED TEACHERS OF NEW ORLEANS AN ABSTRACT SUBMITTED ON THE FIFTH DAY OF MARCH 2021 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CITY, CULTURE AND COMMUNITY-SOCIOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LIBERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JESSE CHANIN APPROVED: ______________________________ Patrick Rafail, Ph.D. Director ______________________________ Jana Lipman, Ph.D. ______________________________ Stephen Ostertag, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation tells the story of the United Teachers of New Orleans (UTNO) from 1965, when they first launched their collective bargaining campaign, until 2008, three years after the storm. I argue that UTNO was initially successful by drawing on the legacy and tactics of the civil rights movement and explicitly combining struggles for racial and economic justice. Throughout their history, UTNO remained committed to civil rights tactics, such as strong internal democracy, prioritizing disruptive action, developing Black and working class leadership, and aligning themselves with community-driven calls for equity. These were the keys to their success. By the early 1990s, as city demographics shifted, the public schools were serving a majority working class Black population. Though UTNO remained committed to some of their earlier civil rights-era strategies, the union became less radical and more bureaucratic. They also faced external threats from the business community with growing efforts to privatize schools, implement standardized testing regimes, and loosen union regulations. I argue that despite the real challenges UTNO faced, they continued to anchor a Black middle class political agenda, demand more for the public schools, and push the statewide labor movement to the left. -

Unequal Origins, Unequal Trajectories: Social Stratification Over the Life Course by Siwei Cheng

Unequal Origins, Unequal Trajectories: Social Stratification over the Life Course by Siwei Cheng A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Public Policy and Sociology) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Yu Xie, Co-Chair Professor Mary E. Corcoran, Co-Chair Professor Jennifer S. Barber Professor Jeffrey Andrew Smith i Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank my co-chair in Sociology, Yu Xie, for his invaluable guidance and support in the past six years. I am very grateful to him not just for teaching me lots of things, but also for teaching me how little I know. He taught me that it is exactly the knowledge of our “knowing nothing” that pushes scholars to be extremely careful and cautious in searching for the truth. This is indeed an important piece of advice that I will keep in mind for many years throughout my research career. I am greatly indebted to my co-chair in Public Policy, Mary Corcoran, for her endless encouragement and support. When I started my dissertation work, I was better at speaking in equations than I was better at speaking in English. Mary always teaches me how to “translate” equations and statistical methods into clear, strong, and meaningful language. My other committee members have been tremendously helpful and supportive as I progressed through my dissertation. Jennifer Barber taught me how to be a devoted researcher at work and an excellent teacher in class. Her expertise in family demography has always been a valuable asset to me. -

The Emerging Field of Video Gaming in India

Video Gaming Parlours: The Emerging Field of Video Gaming in India A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2016 Gagunjoat S. Chhina School of Social Sciences Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 4 The Emergence of Video Gaming in India......................................................................... 5 Declaration ............................................................................................................................. 6 Copyright statement ............................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1. Video gaming in India: The Emergence and Social Construction ....................... 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 8 Organisation of the Thesis .................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 2. Surveying the Field of Video Gaming................................................................ 21 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 21 Theoretical Debates: Narrative and Ludic Approaches -

Social Protection Under Authoritarianism: Politics and Policy of Social Health Insurance in China

Social Protection under Authoritarianism: Politics and Policy of Social Health Insurance in China Xian Huang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Science Columbia University 2014 © 2014 Xian Huang All rights reserved ABSTRACT Social Protection under Authoritarianism: Politics and Policy of Social Health Insurance in China Xian Huang Does authoritarian regime provide social protection to its people? What is the purpose of social welfare provision in an authoritarian regime? How is social welfare policy designed and enforced in the authoritarian and multilevel governance setting? Who gets what, when and how from the social welfare provision in an authoritarian regime? My dissertation investigates these questions through a detailed study of Chinese social health insurance from 1998 to 2010. I argue and empirically show that the Chinese social health insurance system is characterized by a nationwide stratification pattern as well as systematic regional differences in generosity and coverage of welfare benefits. I argue that the distribution of Chinese social welfare benefits is a strategic choice of the central leadership who intends to maintain particularly privileged provisions for the elites whom are considered important for social stability while pursuing broad and modest social welfare provisions for the masses. Provisions of the welfare benefits are put in practice, however, through an interaction between the central leaders who care most about regime stability and the local leaders who confront distinct constraints in local circumstances such as fiscal stringency and social risk. The dynamics of central-local interactions stands at the core of the politics of social welfare provision, and helps explain the remarkable subnational variation in social welfare under China’s authoritarian yet decentralized system. -

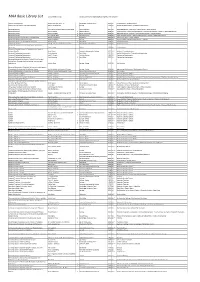

MAA Basic Library List Last Updated 1/23/18 Contact Darren Glass ([email protected]) with Questions

MAA Basic Library List Last Updated 1/23/18 Contact Darren Glass ([email protected]) with questions Additive Combinatorics Terence Tao and Van H. Vu Cambridge University Press 2010 BLL Combinatorics | Number Theory Additive Number Theory: The Classical Bases Melvyn B. Nathanson Springer 1996 BLL Analytic Number Theory | Additive Number Theory Advanced Calculus Lynn Harold Loomis and Shlomo Sternberg World Scientific 2014 BLL Advanced Calculus | Manifolds | Real Analysis | Vector Calculus Advanced Calculus Wilfred Kaplan 5 Addison Wesley 2002 BLL Vector Calculus | Single Variable Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Calculus | Advanced Calculus Advanced Calculus David V. Widder 2 Dover Publications 1989 BLL Advanced Calculus | Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Vector Calculus Advanced Calculus R. Creighton Buck 3 Waveland Press 2003 BLL* Single Variable Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Calculus | Advanced Calculus Advanced Calculus: A Differential Forms Approach Harold M. Edwards Birkhauser 2013 BLL** Differential Forms | Vector Calculus Advanced Calculus: A Geometric View James J. Callahan Springer 2010 BLL Vector Calculus | Multivariable Calculus | Calculus Advanced Calculus: An Introduction to Analysis Watson Fulks 3 John Wiley 1978 BLL Advanced Calculus Advanced Caluculus Lynn H. Loomis and Shlomo Sternberg Jones & Bartlett Publishers 1989 BLL Advanced Calculus Advanced Combinatorics: The Art of Finite and Infinite Expansions Louis Comtet Kluwer 1974 BLL Combinatorics Advanced Complex Analysis: A Comprehensive Course in Analysis, -

Sociological Theory SOC 302

COURSE MANUAL Types of Sociological Theory SOC 302 University of Ibadan Distance Learning Centre Open and Distance Learning Course Series Development i Copyright © 2016 by Distance Learning Centre, University of Ibadan, Ibadan. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN 978-021-519-0 General Editor : Prof. Bayo Okunade University of Ibadan Distance Learning Centre University of Ibadan, Nigeria Telex: 31128NG Tel: +234 (80775935727) E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.dlc.ui.edu.ng ii Vice-Chancellor’s Message The Distance Learning Centre is building on a solid tradition of over two decades of service in the provision of External Studies Programme and now Distance Learning Education in Nigeria and beyond. The Distance Learning mode to which we are committed is providing access to many deserving Nigerians in having access to higher education especially those who by the nature of their engagement do not have the luxury of full time education. Recently, it is contributing in no small measure to providing places for teeming Nigerian youths who for one reason or the other could not get admission into the conventional universities. These course materials have been written by writers specially trained in ODL course delivery. The writers have made great efforts to provide up to date information, knowledge and skills in the different disciplines and ensure that the materials are user- friendly. In addition to provision of course materials in print and e-format, a lot of Information Technology input has also gone into the deployment of course materials. -

103-123 Mackintosh

SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY IN THE SHADOW OF DURKHEIM’S REVOLT AGAINST ECONOMICS Kenneth H. Mackintosh* Having observed that analysis in the cultural sciences devel- ops only through “special and ‘one-sided’ viewpoints,” Max We- ber concluded that “knowledge of the universal . is never valu- able in itself.”1 And thus, however firmly the descriptive re- search which Weber encouraged, and to which he so amply con- tributed, may have established a disciplinary claim for sociolo- gy, it cannot be surprising that its standing as a theoretical sci- ence remains open to question.2 In one of the ironies of modern scholarship, Weber is presented to sociology students, in the com- pany of Durkheim and Marx, as preeminent among those who es- tablished a firm theoretical foundation for the discipline.3 But for the addition of Marx to his very short list, Parsons’s4 coup de theatre still finds its resonance in sociological theory. Over the span of one hundred and fifty years, dissatisfaction with one or more of the fundamental postulates of theoretical economics has given impetus to the development of new “theoret- ical” sciences. Depending upon one’s viewpoint, scientific social- ism, sociology, institutional economics, and so on may represent several such attempts, or they may represent a single multifac- eted effort. Whichever the case, the order of procedure in such undertakings is straightforward. The invention of a new theoret- ical social science can be accomplished by rejecting or otherwise vacating one of the basic postulates of theoretical economics. The starting point may be circumstantial, but if the task is carried forward with any attention to logical consistency, it will lead necessarily to the rejection of every postulate.