Download PDF -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

Senza Titolo-1

copertina_CILENTO2012_Layout 1 01/02/12 12:45 Pagina 1 C IL ENT O E E VA LLO D I DIANO www.incampania.com CILENTO AND THE VALLO DI DIANO Assessorato al Turismo e ai Beni Culturali CILENTO E VALLO DI DIANO CILENTO AND THE VALLO DI DIANO Regione Campania Assessorato al Turismo e ai Beni Culturali www.incampania.com EPT Salerno Via Velia, 15 - 84125 tel. 089 230 411 www.eptsalerno.it Foto Banca immagini Regione Campania Gruppo Associati Pubblitaf Massimo Pica, Pio Peruzzini Salerno CILENTO E VALLO DI DIANO CILENTO AND THE VALLO DI DIANO SOMMARIO / INDEX 7. INTRODUZIONE: CILENTO E VALLO DI DIANO PREFACE: CILENTO AND THE VALLO DI DIANO 11. DA PAESTUM AD ASCEA FROM PAESTUM TO ASCEA 37. DA PISCIOTTA A PUNTA DEGLI INFRESCHI FROM PISCIOTTA TO PUNTA DEGLI INFRESCHI 47. DA SAN GIOVANNI A PIRO AI PAESI DELL’ALTO GOLFO DI POLICASTRO FROM SAN GIOVANNI A PIRO TO THE UPPER POLICASTRO GULF 61. IL CILENTO INTERNO THE HINTERLAND OF CILENTO 83. DALLE GOLE DEL CALORE ALLA CATENA MONTUOSA DEGLI ALBURNI FROM THE GORGE OF THE RIVER CALORE TO THE ALBURNI MOUNTAIN RANGE 97. IL VALLO DI DIANO THE VALLO DI DIANO 117.. ENOGASTRONOMIA FOOD AND WINE 121.. INFORMAZIONI UTILI USEFUL INFORMATION Primula di Palinuro CILENTO E VALLO DI DIANO CILENTO AND THE VALLO DI DIANO Terra antichissima – l’attuale conforma- The current geomorphological forma- zione geo-morfologica viene fatta risalire tion of Cilento, an ancient land that is a dagli esperti a 500.000 anni fa – il Cilento veritable treasure trove, is estimated by è un autentico scrigno di tesori. -

Salerno and Cilento

Salerno and Cilento 106 Arconte Cove 107 Salerno is a fascinating synthesis of what the Mediterranean can offer to those who want to know i it better. The city is continuously improving to better host tourists and visitors from all over the world. Its province is the largest of the Campania. Together with the Amalfi Coast, the archaeological areas of Paestum and the uncontaminated Cilento, it also Ente Provinciale per il includes the high plains crossed by the Sele River, Turismo di Salerno its tributaries and the Vallo di Diano. via Velia 15 tel. 089 230411 www.eptsalerno.it informazioni e acc. turistica piazza Vittorio Veneto,1 tel. 089 231432 Azienda Autonoma di Cura Soggiorno e Turismo di Salerno Lungomare Trieste 7/9 tel. 089 224916 www.aziendaturismo.sa.it Azienda Autonoma di Cura Soggiorno e Turismo di Cava de’ Tirreni Corso Umberto I 208 tel. 089 341605 www.cavaturismo.sa.it Azienda Autonoma di Cura Soggiorno e Turismo di Paestum via Magna Grecia 887 tel. 0828 811016 www.infopaestum.it Ente Parco del Cilento e del Vallo di Diano piazza Santa Caterina, 8 Vallo della Lucania tel. 0974 719911 www.cilentoediano.it Comunità Montana Monti Picentini via Santa Maria a Vico Giffoni Valle Piana tel. 089 866160 Cava de’ Tirreni the School of Medicine then universities of Bologna and Complesso dell’ Abbazia functioning at Velia. In the Padova were founded. della SS Trinità - via Morcaldi 6 13 th century it obtained the The School continued to tel. 089 463922 right to be the only School function until 1812, when it was finally closed by Paestum the School of Medicine of Medicine of the realm Joachim Murat. -

Chapter 1 Multiple Choice 1. an Important Series of Caves With

Chapter 1 Multiple Choice 1. An important series of caves with paintings from the Paleolithic period is located in ________. a. Italy b. England c. Germany d. France Answer: d 2. Which of the following describes the Venus of Willendorf? a. It is a large Neolithic tomb figure of a woman b. It is a small Paleolithic engraving of a woman c. It is a large Paleolithic rockcut relief of a woman d. It is a small Paleolithic figurine of a woman Answer: d 3. Which of the following animals appears less frequently in the Lascaux cave paintings? a. bison b. horse c. bull d. bear Answer: d 4. In style and concept the mural of the Deer Hunt from Çatal Höyük is a world apart from the wall paintings of the Paleolithic period. Which of the following statements best supports this assertion? a. the domesticated animals depicted b. the subject of the hunt itself c. the regular appearance of the human figure and the coherent groupings d. the combination of men and women depicted Answer: c 5. Which of the following works of art was created first? a. Venus of Willendorf b. Animal frieze at Lascaux c. Apollo 11 Cave plaque d. Chauvet Cave Answer: d 6. One of the suggested purposes for the cave paintings at Altamira is thought to have been: a. decoration for the cave b. insurance for the survival of the herd c. the creation myth of the tribal chief d. a record of the previous season’s kills Answer: b 7. The convention of representing animals' horns in twisted perspective in cave paintings or allowing the viewer to see the head in profile and the horns from the front is termed __________. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Achilles (subject) 42–43, 140, 156, 161, 170, 291; Arches Basilica 81 Figs. 2.23, 6.26, 10.19 Arc de Triomphe, Paris 359–360; Aemilia 135–136; Fig. 5.22 acroterion 33, 37, 39; Fig. 2.14 Fig. 12.26 Constantine, Trier 338–339; Figs. 12.4–12.5 Actaeon (subject) 176, 241; Figs. 6.33, 8.34 Arcus Novus, Rome 311 Nova, Rome 340; Figs. 12.6–12.7 Adamclisi, Tropaeum Traiani 229–230; of Argentarii, Rome 287; Figs. 10.14, 10.15 Pompeii 81–83; Figs. 4.5, 4.6 Figs. 8.20–8.21 of Constantine, Rome 341–346; Severan, Lepcis Magna 296, 299; adlocutio 116, 232, 256; Figs. 5.2, 8.24, 9.13 Figs. 12.8–12.11 Figs. 10.26–10.27 adventus 63, 203, 228, 256, 313, 350; of Galerius, Thessalonica 314–315; Ulpia, Rome 216; Fig. 8.5 Figs. 7.25, 8.23 Figs. 11.15–11.16 Baths aedicular niche 133; Fig. 5.20 of Marcus Aurelius, Rome 256; Fig. 9.13 of Agrippa, Rome 118, 185, 279 aedile 12 of Septimius Severus, Lepcis of Caracalla, Rome 279–283; Aemilius Paullus 16, 65, 126 Magna 298–299; Figs. 10.28, 10.29 Figs. 10.7–10.10 Victory Monument 16, 107–108; of Septimius Severus, Rome 284–286; of Cart Drivers, Ostia 242–244; Fig. 8.37 Figs. 4.30, 4.31 Figs. 10.11–10.13 of Diocletian, Rome 320–322; Aeneas 27, 121, 122, 126, 127, 135, 140, 156, of Titus, Rome 201–203; Figs. 7.22–7.24 Figs. -

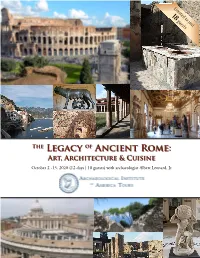

The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 2 -13, 2020 (12 Days | 18 Guests) with Archaeologist Albert Leonard, Jr

Limited to just Limited to just 18 18 travelers guests © Derbrauni The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 2 -13, 2020 (12 days | 18 guests) with archaeologist Albert Leonard, Jr. Dear Traveler, Next October, when the weather is typically perfect, discover the glorious legacy of ancient Rome with the AIA’s Dr. Al Leonard, recipient of many awards and a popular AIA Tours lecturer and host. With expert local guides plus a professional tour manager to handle all of the logistics, you can relax and immerse yourself in learning and experiencing ancient and Renaissance art and architecture, including numerous UNESCO World Heritage sites. Enjoy delicious food and wine, and excellent, 4-star hotels, perfectly located for exploring on your own during free time: five nights in central Rome, two nights in Naples overlooking the Bay of Naples, and three nights in Amalfi overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea. © Carla Tavares Highlights are many and include: • The Roman Forum, with a private visit to the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina; and special entry to the Colosseum's upper levels; • Stunning paintings and mosaics at the House of Augustus on the Palatine Hill; • The Capitoline Museums, with their magnificent Classical and Renaissance art; • Outstanding Renaissance sculptures and paintings at the Borghese Gallery; • A day trip to Tivoli for visits to Hadrian’s Villa, a 2nd-century A.D. complex; and Villa d’Este, a superb Renaissance palace. • Breakfast within the Vatican Museums, before entering the Sistine Chapel © Intel Free -

The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 14 -25, 2021 (12 Days | 16 Guests) with Archaeologist Ingrid Rowland

Limited to just Limited to just 18 16 travelers guests © Derbrauni © operator The Legacy of Ancient Rome: Art, Architecture & Cuisine October 14 -25, 2021 (12 days | 16 guests) with archaeologist Ingrid Rowland © MrNo “The archaeological sites are the things that caused me to select Archaeological Institute of this tour. The great buildings and ensembles of architectural America Lecturer and Host interest were such a thrill that I will never forget.” - Charles, New York Ingrid Rowland first came to Italy on the ocean liner Leonardo da Vinci. With a Ph.D. in Greek ITALY Adriatic Sea and Classical Tivoli Archaeology 5 ROME from Bryn Mawr, Sperlonga she branched out into Renaissance Capua Herculaneum and Baroque NAPLES 3 studies, and Tyrrhenian Sea Capri 2 AMALFI recently into Paestum contemporary art. Ingrid has studied and Pompeii taught in Rome for many years, and is now Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame’s Rome Global Gateway. Prior to that appointment, she served as the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the = Flights Humanities at the American Academy in = Itinerary stops Rome (2001-05), and then Professor in the = Overnight stays Rome Program of the Notre Dame School of Architecture (2005-). A frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books, she has written more than a dozen books on Italian subjects, ranging from the ancient Etruscans to the present day, including The Divine Spark of Syracuse (2018), From Pompeii: The Afterlife of a Roman Town (2015), and, with Noah Charney, The Collector of Lives: Giorgio Vasari and the Invention of Art (2017). -

The Roman Banquet Images of Conviviality

P1: FCH/SPH P2: FCH/SPH QC: FCH/SPH T1: FCH CB568-FM CB568-Dunbabin-v3 June 28, 2003 11:19 The Roman Banquet Images of Conviviality Katherine M. D. Dunbabin McMaster University iii P1: FCH/SPH P2: FCH/SPH QC: FCH/SPH T1: FCH CB568-FM CB568-Dunbabin-v3 June 28, 2003 11:19 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB22RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Katherine M. D. Dunbabin 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typefaces Bembo 11/14 pt. and Cochin System LATEX 2ε [TB] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Dunbabin, Katherine M. D. The Roman banquet: images of conviviality / Katherine M. D. Dunbabin p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-521-82252-1 1. Gastronomy – Rome – History. 2. Dinners and dining – Rome – History. I. Title. TX641 .D85 2003 641.0130937 – dc21 2003043509 ISBN 0 521 82252 1 hardback iv P1: FCH/SPH P2: FCH/SPH QC: FCH/SPH T1: FCH CB568-FM CB568-Dunbabin-v3 June 28, 2003 11:19 Contents List of Illustrations.................................................................ix Preface.............................................................................xv Introduction ........................................................................1 Chapter 1. -

Rome & Bay of Naples 2 Centre Location Guide Classics

ROME & BAY OF NAPLES 2 CENTRE LOCATION GUIDE CLASSICS Exceptional Tours Expertly Delivered Our location guide offers you information on the range of visits available in the Bay of Naples. All visits are selected with your subject and the curriculum in mind, along with the most popular choices for sightseeing, culture and leisure in the area. The information in your location guide has been provided by our partners in the Bay of Naples who have expert on the ground knowledge of the area, combined with advice from education professionals so that the visits and information recommended are the most relevant to meet your learning objectives. Making Life Easier for You This location guide is not a catalogue of opening times. Our Tour Experts will design your itinerary with opening times and location in mind so that you can really maximise your time on tour. Our location guides are designed to give you the information that you really need, including what are the highlights of the visit, location, suitability and educational resources. We’ll give you top tips like when is the best time to go, dress code and extra local knowledge. Peace of Mind So that you don’t need to carry additional money around with you we will state in your initial quote letter, which visits are included within your inclusive tour price and if there is anything that can’t be pre-paid we will advise you of the entrance fees so that you know how much money to take along. You also have the added reassurance that, WST is a member of the STF and our featured visits are all covered as part of our externally verified Safety Management System. -

Amalfi Coast Walking Tour + CAPRI & NAPLES EXTENSION

2015 Amalfi Coast Walking Tour + CAPRI & NAPLES EXTENSION 10 Azure seascapes and beautiful scenery await. DAYS American author John Steinbeck once wrote that Italy’s Amalfi Coast “is a dream place that isn’t quite real when you are there and becomes beckoningly real after you have gone.” This is one of those rare places 13 DAYS WITH EXTENSION where photographs simply don’t do its sights justice—you need to see them for yourself. On this walking Walking Tour tour through the seaside villages of the Amalfi Coast, you’ll do just that. Start planning today 1.800.206.9871 | goaheadtours.com/wam © 2015 EF Cultural Travel LTD 2015 Overview AMALFI COAST WALKING TOUR Let us handle the details Expert Local Handpicked Sightseeing with Private Personalized Tour Director cuisine hotels local guides transportation flight options Your tour includes Your tour highlights • 8 nights in hand-picked hotels • Pizza will never taste the same again • Breakfast daily, 3 three-course dinners with beer or wine • The stunning Villas Rufolo and Cimbrone and their beautiful gardens • Multilingual Tour Director • Leisure is a way of life on the Amalfi Coast • Private deluxe motor coach • Locals walk you through cities’ unseen treasures • 4 escorted walks • Views from atop Vesuvius to underground Naples • Guided sightseeing and select entrance fees • Stunning seaside Sorrento Where you’ll go OVERNIGHT STAYS 2 nights • Naples 6 nights • Sorrento ITALY Naples Pompeii Amalfi Coast + Capri & Naples Extension Sorrento MAXIMUM GROUP SIZE FOR THIS TOUR ABOUT YOUR HOTELS 28 With our Right Size Advantage, your group will never get in the way of Our 3- and 4-diamond accommodations are handpicked to your experience. -

Winter 2015 Sortes

Sortes ~ Winter 2015 December 1, 2015 Dear members of the Vergilian Society, As I near the end of my second year as President of the Vergilan Society I reflect both on the challenges with which we have been confronted in the past year, and also on the progress and sense of cooperation that is evi- dent in the work and contributions made by a number of people in the Society. I want to express my gratitude to members of the Board who have given freely and generously of their time; we are fortunate to have such commit- ted officers, particularly at a somewhat challenging time. At our 2014 Board meeting, the Treasurer reported a substantial operating loss. In my letter last year I accord- ingly began “I feel less cheerful about the current financial situation”, with details that justified that sense. I am pleased to report that there are grounds for mild optimism. Athough we had to cancel and issue refunds for our scheduled tour to Tunisia, the tours we did mount did reasonably well, while the summer’s Symposium Cuma- num on “Virgil and Roman Religion” was a great success intellectually, and also helped financially. At this year’s Board meeting the Treasurer noted modest yet real improvement in our financial situation: The Society recorded a net operating loss of $2,089 for the year, compared to the previous year’s net operating loss of $23,513. The budget for the year had projected a net loss of $43,725, so actual re- sults were $41,636 better than expected. -

From Greek Temples to Roman Holiday Homes: Sicily, Pompeii, and the Villa Oplontis May 28 – June 8, 2017

From Greek Temples to Roman Holiday Homes: Sicily, Pompeii, and the Villa Oplontis May 28 – June 8, 2017 The School for Advanced Research is able to offer a unique opportunity to its members in a place that has been the epicenter of archaeological travel since the eighteenth century. We begin in Sicily with the Greeks and their acropoli, temples, theaters, and fortresses, some rarely visited, others like the Fountains of Arethuse, revered over the centuries—from Pindar to Pope. We cross over into Reggio Calabria, see the famous Warriors of Riace, then on to Paestum, and then into the Roman world of Herculaneum, Pompeii, and the villas of the Bay of Naples. The capstone of the trip will be an utterly unique opportunity to join the site director for a custom tour during the final field season at the country home of one of Nero’s more notorious wives, Poppaea Sabina. Also known as the Villa Oplontis, the complex features extraordinary frescos rivaling those found elsewhere in the ancient world, and its overall condition has made it the subject of one of the most comprehensive 3D visualization projects in the world. This is an opportunity not only to explore some of the most intriguing and inspiring places in the ancient world in a new way, but to experience Italy in its most sublime season. Sunday, May 28: PALERMO (D) We arrive in Palermo on Sunday. During the evening we will have dinner and an opening lecture. Hotel: Mercure Excelsior Hotel, Palermo. Monday, May 29: PALERMO (B/L) Our touring begins at La Zisa, a Norman-Arab mansion housing the Museum of Islamic Art.