Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

EDCN-806E-Education for Empowerment of Women.Pdf

EDUCATION FOR EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN MA [Education] Second Semester EDCN 806E [ENGLISH EDITION] Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY Reviewer Dr Sitesh Saraswat Reader, Bhagwati College of Education, Meerut Authors Dr Namrata Prasad: Units (1.0-1.3, 1.4, 1.6-1.10, 2.6.1) © Dr Namrata Prasad, 2016 Dr Md Arshad: Units (1.3.1, 1.5) © Dr Md Arshad, 2016 Vivek Kumar: Units (2.0-2.6, 2.7-2.11, 3) © Reserved, 2016 Paulie Jindal: Units ( 4 & 5) © Reserved, 2016 Books are developed, printed and published on behalf of Directorate of Distance Education, Tripura University by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material, protected by this copyright notice may not be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form of by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the DDE, Tripura University & Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio

SR NO First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 A SPRAKASH REDDY 25 A D REGIMENT C/O 56 APO AMBALA CANTT 133001 0000IN30047642435822 22.50 2 A THYAGRAJ 19 JAYA CHEDANAGAR CHEMBUR MUMBAI 400089 0000000000VQA0017773 135.00 3 A SRINIVAS FLAT NO 305 BUILDING NO 30 VSNL STAFF QTRS OSHIWARA JOGESHWARI MUMBAI 400102 0000IN30047641828243 1,800.00 4 A PURUSHOTHAM C/O SREE KRISHNA MURTY & SON MEDICAL STORES 9 10 32 D S TEMPLE STREET WARANGAL AP 506002 0000IN30102220028476 90.00 5 A VASUNDHARA 29-19-70 II FLR DORNAKAL ROAD VIJAYAWADA 520002 0000000000VQA0034395 405.00 6 A H SRINIVAS H NO 2-220, NEAR S B H, MADHURANAGAR, KAKINADA, 533004 0000IN30226910944446 112.50 7 A R BASHEER D. NO. 10-24-1038 JUMMA MASJID ROAD, BUNDER MANGALORE 575001 0000000000VQA0032687 135.00 8 A NATARAJAN ANUGRAHA 9 SUBADRAL STREET TRIPLICANE CHENNAI 600005 0000000000VQA0042317 135.00 9 A GAYATHRI BHASKARAAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041978 135.00 10 A VATSALA BHASKARAN 48/B16 GIRIAPPA ROAD T NAGAR CHENNAI 600017 0000000000VQA0041977 135.00 11 A DHEENADAYALAN 14 AND 15 BALASUBRAMANI STREET GAJAVINAYAGA CITY, VENKATAPURAM CHENNAI, TAMILNADU 600053 0000IN30154914678295 1,350.00 12 A AYINAN NO 34 JEEVANANDAM STREET VINAYAKAPURAM AMBATTUR CHENNAI 600053 0000000000VQA0042517 135.00 13 A RAJASHANMUGA SUNDARAM NO 5 THELUNGU STREET ORATHANADU POST AND TK THANJAVUR 614625 0000IN30177414782892 180.00 14 A PALANICHAMY 1 / 28B ANNA COLONY KONAR CHATRAM MALLIYAMPATTU POST TRICHY 620102 0000IN30108022454737 112.50 15 A Vasanthi W/o G -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 01.01.001 Z.P.BOYS JUNIOR COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 66 66 66 0 0 0 66 100.00 27050803901 ARTS 14 14 7 7 0 0 14 100.00 COMMERCE 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 100.00 TOTAL 81 81 74 7 0 0 81 100.00 01.01.002 GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AKOLA SCIENCE 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 27050117183 TOTAL 17 17 16 1 0 0 17 100.00 01.01.003 R.L.T. SCIENCE COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE SCIENCE 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 27050117184 TOTAL 544 544 543 1 0 0 544 100.00 01.01.004 SHRI.SHIVAJI ARTS COMMERCE & SCIENCE SCIENCE 238 238 238 0 0 0 238 100.00 27050117186 COLLEGE,AKOLA ARTS 160 160 60 100 0 0 160 100.00 COMMERCE 183 183 110 73 0 0 183 100.00 TOTAL 581 581 408 173 0 0 581 100.00 01.01.005 SMT L.R.T. COMMERCE COLLEGE , AKOLA COMMERCE 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 27050117187 TOTAL 761 761 748 12 1 0 761 100.00 01.01.006 SITABAI ARTS COLLEGE, AKOLA CIVIL LINE ROAD SCIENCE 7 7 7 0 0 0 7 100.00 27050119003 ARTS 111 111 47 61 3 0 111 100.00 COMMERCE 105 105 97 8 0 0 105 100.00 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC 2021 Candidates passed College No. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Chapter 5 - Architectural and Urban Patronage

CHAPTER 5 - ARCHITECTURAL AND URBAN PATRONAGE In 1779 CE Ahilyābāī Hoḷkar sent a letter to Gopikābāī Peśvā, grandmother of the then Peśvā, Savāī Mādhavrāv and the wife of Nānāsāheb Peśvā. Some years before, Gopikābāī, who was staying at Nāśik, had constructed a kuṅda and ghāṭ on the Godāvarī River known respectively as Rāmkuṅda and Rāmghāṭ. Ahilyābāī wrote to Gopikābāī requesting for permission to repair and rebuild the same in a more artistic manner. Gopikābāī flatly refused any such permission saying that the kuṅda and ghāṭ were meant to preserve her memories which she did not want to be destroyed (Sathe, 2013, p. 143). Ahilyābāī retaliated by not sending the sarees that Gopikābāī had requested from Maheshwar. It was an act of what Bourdieu has termed as ‘symbolic violence’, a strategy employed by those having legitimacy in the social field to maintain their positions from any competition. Clearly, Gopikābāī saw Ahilyābāī’s intervention as a threat to her authority. This apparently simple event shows the acute awareness that patrons had, of the power of architecture in consolidating their social positions. They used architecture consciously to further their social and political aims. What purposes did the construction projects serve beyond the mere function? How were buildings used by the agents to assert authority and consolidate social positions? Can we trace any thematic continuity between the patronage of preceding centuries and the eighteenth century? This chapter attempts to answer such questions by focusing on patronage and matronage in the study area. Patronage and its relationship with architecture has been an important concern for a number of years in Historical studies. -

THE Tl1ird ENGLISH EMBASSY to POON~

THE Tl1IRD ENGLISH EMBASSY TO POON~ COMPRISING MOSTYN'S DIARY September, 1772-February, 1774 AND MOSTYN'S LETTERS February-177 4-Novembec- ~~:;, EDITED BY ]. H. GENSE, S. ]., PIL D. D. R. BANAJI, M. A., LL. B. BOMBAY: D. B. TARAPOREV ALA SONS & CO. " Treasure House of Books" HORNBY ROAD, FORT· COPYRIGHT l934'. 9 3 2 5.9 .. I I r\ l . 111 f, ,.! I ~rj . L.1, I \! ., ~ • I • ,. "' ' t.,. \' ~ • • ,_' Printed by 1L N. Kulkarni at the Katnatak Printing Pr6SS, "Karnatak House," Chira Bazar, Bombay 2, and Published by Jal H. D. Taraporevala, for D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Hornby Road, Fort, Bombay. PREFACE It is well known that for a hundred and fifty years after the foundation of the East India Company their representatives in ·India merely confined their activities to trade, and did not con· cern themselves with the game of building an empire in the East. But after the middle of the 18th century, a severe war broke out in Europe between England and France, now known as the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which soon affected all the colonies and trading centres which the two nations already possessed in various parts of the globe. In the end Britain came out victorious, having scored brilliant successes both in India and America. The British triumph in India was chiefly due to Clive's masterly strategy on the historic battlefields in the Presidencies of Madras and Bengal. It should be remembered in this connection that there was then not one common or supreme authority or control over the three British establishments or Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. -

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD and SATI One Unavoidable and Important

CHAPTER 5 WIDOWHOOD AND SATI One unavoidable and important consequence of child-inan iages and the practice of polygamy w as a \ iin’s premature widowhood. During the period under study, there was not a single house that did not had a /vidow. Pause, one of the noblemen, had at one time 57 widows (Bodhya which meant widows whose heads A’ere tonsured) in the household A widow's life became a cruel curse, the moment her husband died. Till her husband was alive, she was espected and if she had sons, she was revered for hei' motherhood. Although the deatli of tiie husband, was not ler fault, she was considered inauspicious, repellent, a creature to be avoided at every nook and comer. Most of he time, she was a child-widow, and therefore, unable to understand the implications of her widowhood. Nana hadnavis niiirried 9 wives for a inyle heir, he had none. Wlien he died, two wives survived him. One died 14 Jays after Nana’s death. The other, Jiubai was very beautiful and only 9 years old. She died at the age of 66 r'ears in 1775 A.D. Peshwa Nanasaheb man'ied Radhabai, daugliter of Savkar Wakhare, 6 months before he died, Radhabai vas 9 years old and many criticised Nanasaheb for being mentally derailed when he man ied Radhabai. Whatever lie reasons for this marriage, he was sui-vived by 2 widows In 1800 A.D., Sardai' Parshurarnbhau Patwardlian, one of the Peshwa generals, had a daughter , whose Msband died within few months of her marriage. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

Professional-Address.Pdf

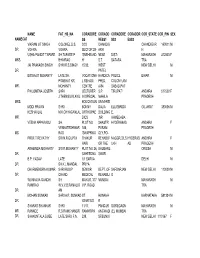

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR.