Fashioning the Pious Self: Middle Class Religiosity in Colonial India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd, MS/Mphil BS/Bsc (Hons) 2021-22 GCU

PhD, MS/MPhil BS/BSc (Hons) GCU GCU To Welcome 2021-22 A forward-looking institution committed to generating and disseminating cutting- GCUedge knowledge! Our vision is to provide students with the best educational opportunities and resources to thrive on and excel in their careers as well as in shaping the future. We believe that courage and integrity in the pursuit of knowledge have the power to influence and transform the world. Khayaali Production Government College University Press All Rights Reserved Disclaimer Any part of this prospectus shall not be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from Government CONTENTS College University Press Lahore. University Rules, Regulations, Policies, Courses of Study, Subject Combinations and University Dues etc., mentioned in this Prospectus may be withdrawn or amended by the University authorities at any time without any notice. The students shall have to follow the amended or revised Rules, Regulations, Policies, Syllabi, Subject Combinations and pay University Dues. Welcome To GCU 2 Department of History 198 Vice Chancellor’s Message 6 Department of Management Studies 206 Our Historic Old Campus 8 Department of Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Studies 214 GCU’s New Campus 10 Department of Political Science 222 Department of Sociology 232 (Located at Kala Shah Kaku) 10 Journey from Government College to Government College Faculty of Languages, Islamic and Oriental Learning University, Lahore 12 Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies 242 Legendary Alumni 13 Department of -

International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding (IJMMU) Vol

Comparative Study of Post-Marriage Nationality Of Women in Legal Systems of Different Countries http://ijmmu.com [email protected] International Journal of Multicultural ISSN 2364-5369 Volume 2, Issue 6 and Multireligious Understanding December, 2015 Pages: 41-57 Public Perception on Calligraphic Woodcarving Ornamentations of Mosques; a Comparison between East Coast and Southwest of Peninsula Malaysia Ahmadreza Saberi1; Esmawee Hj Endut1; Sabarinah Sh Ahmad1; Shervin Motamedi2,3; Shahab Kariminia4; Roslan Hashim2,3 1 Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, 40450, Malaysia Email: [email protected] 2 Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 3 Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences (IOES), University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 4 Department of Architecture, Faculty of Art, Architecture and Urban Planning, Najafabad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Najafabad, Isfahan, Iran Abstract Woodcarving ornamentation is considered as, a national heritage and can be found in many Malaysian mosques. Woodcarvings are mostly displayed in three different motifs, namely floral, geometry and calligraphy. The application of floral and geometry motifs is to convey an abstract meaning of Islamic teachings to the viewers. However, the calligraphic decorations directly express the messages of Allah almighty or the sayings of the prophets to the congregations. Muslims are the main users of mosques as these are places for prayers as well as other religious and community activities. Therefore, the assessment of users’ opinion about this type of decoration needs to be investigated. This paper aims to evaluate the perception of two groups of mosque users on the calligraphic woodcarving ornamentations from two regions, namely the East Coast and Southwest of Peninsula Malaysia. -

HAJ COMMITTEE of INDIA Annual Report CONTENTS

HAJ COMMITTEE OF INDIA Annual Report 2014-15 CONTENTS I. Introduction ...................................................................................................1-2 II. Constitution of Haj Committee of India......................................................... 3-5 1. Notification 2. Composition III. Standing / Sub Committees............................................................................ 6-7 IV. Establishment...............................................................................................8-10 V. Meetings and Conference.........................................................................11-12 VI. Haj Policy 2013-2017..................................................................................13-21 VII. Haj Action Plan............................................................................................22-25 VIII. Norms for Haj-2014....................................................................................26-35 1. Haj Application Forms for Haj-2014 2. Distribution of Quota 3. Qurrah (Draw Of Lots) 4. Advance Haj Amount 5. Processing of International Passports 6. Computerization of Data 7. Selection of Pilgrims and Waiting-List Confirmation IX. Visit of Delegation.......................................................................................36-37 1. Building Selection Work For Haj-2014 2. Renting Delegation X. Orientation / Training of Pilgrims for Haj-2014..........................................38-39 XI. Other Arrangements for Pilgrims of Haj-2014............................................40-42 -

The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924)

The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924) The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924) * Turab-ul-Hassan Sargana **Khalil Ahmed ***Shahid Hassan Rizvi Abstract The main objective of the present study is to explain the role of the Deobandi faction of scholars in Indian Freedom Movement. In fact, there had been different schools of thought who supported the Movement and their works and achievements cannot be forgotten. Historically, Ulema played a key role in the politics of subcontinent and the contribution of Dar ul Uloom Deoband, Mazahir-ul- Uloom (Saharanpur), Madrassa Qasim-ul-Uloom( Muradabad), famous madaris of Deobandi faction is a settled fact. Their role became both effective and emphatic with the passage of time when they sided with the All India Muslim League. Their role and services in this historic episode is the focus of the study in hand. Keywords: Deoband, Aligarh Movement, Khilafat, Muslim League, Congress Ulama in Politics: Retrospect: Besides performing their religious obligations, the religious ulema also took part in the War of Freedom 1857, similar to the other Indians, and it was only due to their active participation that the movement became in line and determined. These ulema used the pen and sword to fight against the British and it is also a fact that ordinary causes of 1857 War were blazed by these ulema. Mian Muhammad Shafi writes: Who says that the fire lit by Sayyid Ahmad was extinguished or it had cooled down? These were the people who encouraged Muslims and the Hindus to fight against the British in 1857. -

Muslim Personal Law in India a Select Bibliography 1949-74

MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 1949-74 SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Master of Library Science, 1973-74 DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIEVCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH. Ishrat All QureshI ROLL No. 5 ENROLMENT No. C 2282 20 OCT 1987 DS1018 IMH- ti ^' mux^ ^mCTSSDmSi MUSLIM PERSONAL LAW IN INDIA -19I4.9 « i97l<. A SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRSMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DESIEE OF MASTER .OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, 1973-7^ DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE, ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY, ALIGARH ,^.SHRAT ALI QURESHI Roll No.5 Enrolment Nb.C 2282 «*Z know tbt QUaa of Itlui elaiJi fliullty for tho popular sohools of Mohunodan Lav though thoj noror found it potslbla to dany the thaorotloal peasl^Ultj of a eoqplota Ijtlhad. Z hava triad to azplain tha oauaaa ¥hieh,in my opinion, dataminad tbia attitudo of tlia laaaaibut ainca thinga hcra ehangad and tha world of Ulan is today oonfrontad and affaetad bj nav foroaa sat fraa by tha extraordinary davalopaant of huaan thought in all ita diraetiona, I see no reason why thia attitude should be •aintainad any longer* Did tha foundera of our sehools ever elala finality for their reaaoninga and interpreti^ tionaT Navar* The elaii of tha pxasaat generation of Muslia liberala to raintexprat the foundational legal prineipleay in the light of their ovn ej^arla^oe and the altered eonditlona of aodarn lifs is,in wj opinion, perfectly Justified* Xhe teaehing of the Quran that life is a proeasa of progressiva eraation naeaaaltatas that eaoh generation, guided b&t unhampered by the vork of its predeoessors,should be peraittad to solve its own pxbbleas." ZQ BA L '*W« cannot n»gl«ct or ignoi* th« stupandoits vox^ dont by the aarly jurists but «• cannot b« bound by it; v« must go back to tha original sources 9 th« (^ran and tba Sunna. -

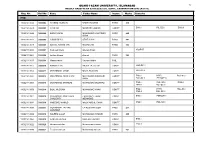

QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD 15 RESULT GAZETTE of B.A/B.Sc/B.Com

15 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc/B.Com. SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2016 (Part-II) Reg. No. Roll No. Name Father Name Status Marks Remarks (002) 110021410024 3000002 NAVEED HUSSAIN NADIR HUSSAIN PASS 395 110021410025 3000003 AYAZ ALI MUMTAZ HUSSAIN COMPT. ENG:I ISL-EDU ENG:II GEO:II 110021410040 3000004 BABAR KHAN MUHAMMAD KHURSHID PASS 465 KHAN 110021410017 3000005 AYMIM SHAH AFIAT KHAN PASS 441 110021410015 3000006 SOHAIL AHMAD JAN MADAD JAN PASS 362 110021310042 3000007 Shahzad Shabir Ghulam Shabir ABSENT 110021310064 3000008 Ashfaq Ahmed Ahmed PASS 389 110021310035 3000009 Waqar Haider Ghulam Haider FAIL 110021410077 3000010 RAHIM U DIN HAJI ALLA UD DIN COMPT. PER(OPT) 110021410055 3000011 MUHAMMAD JASIM MUSA HUSSAIN COMPT. POL-SC:II 110021410052 3000012 MUHAMMAD ASAD KHAN MUHAMMAD SIDDIQUE COMPT. ENG:I HPE:I POL-SC:I KHAN POL-SC:II PER(OPT) 110021410063 3000013 MUHAMMAD SHAHBAZ MUHAMMAD GULFRAZ COMPT. ENG:I POL-SC:I ENG:II HPE:II POL-SC:II 110021410056 3000014 BILAL HUSSAIN MUHAMMAD ANAR COMPT. ENG:I HPE:I POL-SC:I ENG:II POL-SC:II 110021410001 3000015 MUHAMMAD ASIM TAHIR CHAUDHRY TAHIR COMPT. ENG:I PER(OPT) CHAUDHRY MEHMOOD 110021410044 3000016 MAQSOOD AHMED MALIK ABDUL GHANI COMPT. ENG:I POL-SC:I 110021410093 3000017 MUHAMMAD TAYYAB CH AUS MANZOOR PASS 417 MANZOOR 110021410026 3000018 SALEEM ULLAH MUHAMMAD SHOAIB PASS 405 110021410062 3000019 ARSLAN HAIDER SARFRAZ AHMAD COMPT. ENG:I 110021310022 3000020 Muhammad Riaz Muhammad Hussain COMPT. ENG:II 110021310049 3000021 Zeeshan Saleem Muhammad Saleem PASS 427 16 QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY, ISLAMABAD RESULT GAZETTE OF B.A/B.Sc/B.Com. -

Report on Exploratory Study Into Honor Violence Measurement Methods

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Report on Exploratory Study into Honor Violence Measurement Methods Author(s): Cynthia Helba, Ph.D., Matthew Bernstein, Mariel Leonard, Erin Bauer Document No.: 248879 Date Received: May 2015 Award Number: N/A This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this federally funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Report on Exploratory Study into Honor Violence Measurement Methods Authors Cynthia Helba, Ph.D. Matthew Bernstein Mariel Leonard Erin Bauer November 26, 2014 U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics Prepared by: 810 Seventh Street, NW Westat Washington, DC 20531 An Employee-Owned Research Corporation® 1600 Research Boulevard Rockville, Maryland 20850-3129 (301) 251-1500 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Table of Contents Chapter Page 1 Introduction and Overview ............................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Summary of Findings ........................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Defining Honor Violence .................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Demographics of Honor Violence Victims ...................................... 1-5 1.4 Future of Honor Violence ................................................................... 1-6 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................... -

Exhibitions Director Archives Dept

Phone:2561412 rdi I I r 431, SECTOR 2. PANCHKULA-134 112 ; j K.L.Zakir HUA/2006-07/ Secretary Dafeci:")/.^ Subject:-1 Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle'i. Dearlpo ! I The Haryana Urdu Akademi, in collaboration with the District Administration Mewat, proposes to organize a Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle" in the 1st or 2^^ week of November,2006 at Nuh. It is a very important Seminar and everyone has appreciated this proposal. A special meeting was organized a couple of weeks back ,at Nuh. A list ojf the experts/Scholars/persons associated with the families of the freedom fighters was tentatively prepared in that meeting, who could be aiv requ 3Sted to present their papers in the Seminar. Your name is also in this list. therefore, request you to please intimate the title of the paper which you ^ould like to present in the Seminar. The Seminar is expected to be inaugurated by His Excellency the Governor of Haryana on the first day of the Seminar. On the Second day, papers will be presented by the scholars/experts/others and in tlie valedictory session, on the second day, a report of the Seminar will be presented along with the recommendations. I request you to see the possibility of putting up an exhibition during the Seminar at Nuh, in the Y.M.D. College, which would also be inaugurated by His Excellency on the first day and it would remain open for the students of the college ,other educational intuitions and general public, on the second day. -

Os Últimos Momentos Da Vida Dos Piedosos

: Os Últimos Momentos da Vida dos Piedosos Em nome de Allah, o Beneficente, o Misericordioso. Todos os louvores para Allah, o Senhor dos Mundos, e Bênçãos e Saudações sobre o Seu Mensageiro, Muhammad, uma Misericórdia para os Mundos. : Os Últimos Momentos da Vida dos Piedosos SHAIKUL HADITH MOULANA YUSUF MOTALA Todos os direitos reservados. Este livro não pode ser reproduzido, no todo ou em parte, por qualquer processo mecânico, fotográfico, eletrónico, ou por meio de gravação, nem ser introduzido numa base de dados, difundido ou de qualquer forma copiado para uso público ou privado - além do uso legal com o propósito educacional sem fins lucrativos ou breve citação em artigos – sem prévia e expressa autorização do editor. Versão Portuguesa: Ridwan D. Ismael Publicado por: Publicações FIP www.fip.org.pt [email protected] 2018 Distribuído por: Fundação Islâmica de Palmela ÍÍÍNDICE IIINTRODUÇÃO 171717 O carácter dos piedosos 17 A admiração dos Maláikah (Anjos) 18 A morte com o Imán é a maior dádiva 19 Os benefícios da preocupação acerca de Ákhirah (Vida Futura) 20 Este doente vê o amor mas não recupera 21 A referência de ‘Lá Takháfu Walá Tahzanu’ 22 A realidade do temor 23 Allah mostrou a verdade a todos os que têm visão 24 O grau de temor de Sayyiduna Atá Sulami 25 Ajuda! Ajuda! Ó Allah! 27 Ó Senhor, limpa a maldade do íntimo 28 A inquietação de Sayyiduna Sufiyán Çauri 29 O testamento de um Sádiq (verdadeiro) 30 A última ação 30 O temor é uma bênção 31 Outros tipos de temor 32 -

Siddique Phd Complete File for CD March 2020

RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHTS OF MAULANA WAHIDUDDIN KHAN By SIDDIQUE AHMAD SHAH PhD Thesis DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR Session: 2011-2012 RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHTS OF MAULANA WAHIDUDDIN KHAN A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, University of Peshawar in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By SIDDIQUE AHMAD SHAH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR Session: 2011-2012 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis entitled “Religio-Political Thoughts of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan” submitted by Siddique Ahmad Shah in partial fulfillment of requirements for award of Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History is hereby approved. __________________________ External Examiner __________________________ Supervisor Dr. Syed Waqar Ali Shah Department of History University of Peshawar _________________________ Chairman Department of History University of Peshawar DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled “Religio-Political Thoughts of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan” is the outcome of my individual research and it has not been submitted concurrently to any other university for any other degree. Siddique Ahmad Shah PhD Scholar FORWARDING SHEET The thesis entitled “Religio-Political Thoughts of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan ” submitted by Siddique Ahmad Shah , in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History has been completed under my guidance and supervision. I am satisfied with the quality of this research work. Dated: (Dr. Syed Waqar Ali Shah) (Supervisor) To My wife Table of Contents S. No Title Page No. 1. Glossary i 2. Acknowledgements vi 3. Abstract viii 4. Introduction 1-11 5. CHAPTER 1 12-36 Early Life, Education, Mission and Features of Personality 6. -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known.