Three Traditions in Christian Approach to Social Issues in the Context of Church’S Social Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

The Brothers Karamazov in the Prism of Hesychast Anthropology

V. THE UNEVEN PATH OF RUSSIAN SPIRITUALITY 176 The Brothers Karamazov in the Prism of Hesychast Anthropology Sergey Khoruzhy (Institute of Synergetic Anthropology, Moscow) Introduction: The Brothers Karamazov, The Elders and Hesychasm It might seem that everything that can be written on Feodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov has already been written long ago, but nevertheless everywhere in the world this novel continues to be studied and discussed again and again. There is no contradiction in this. We know that people will always turn to The Karamazovs and similar cultural phenomena, not so much for making great new discoveries about these works, as for getting help in discovering and understanding themselves. Such is the role or maybe even definition of truly classical phenomena: they are landmarks in the world of culture, which people of any time use in order to determine their own location in this world. Any time and any cultural community address classical phenomena in their own way. They put their own questions to these phenomena, the questions that are most essential for them and for their self-determination. Choosing my subject, I would like to choose it among these essential questions: What is important in The Karamazovs for our time, for present-day people? The present-day situation, both Russian and global, social and cultural, tells us that the focus of these problems is concentrated in what is happening to the human person: in anthropology. Cardinal changes are taking place, which diverge sharply from classical anthropology. Man shows strong will and irresistible drive to extreme experiences of all kinds, including dangerous, asocial and transgressive ones. -

Essays in the Russian Autocracy

ESSAYS IN THE RUSSIAN AUTOCRACY Vladimir Moss © Vladimir Moss: 2010. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................4 1. THE RISE OF THE RUSSIAN AUTOCRACY ................................................5 The Appeal to Riurik..............................................................................................5 St. Vladimir the Saint............................................................................................7 Church and State in Kievan Rus’..........................................................................8 The Breakup of Kievan Rus’ ................................................................................14 Autocracy restored: St. Andrew of Bogolyubovo.................................................16 2.THE RISE OF MUSCOVY................................................................................22 St. Alexander Nevsky ..........................................................................................22 St. Peter of Moscow .............................................................................................23 St. Alexis of Moscow ...........................................................................................24 St. Sergius of Radonezh.......................................................................................27 3. MOSCOW: THE THIRD ROME .....................................................................30 4.THE HERESY OF THE JUDAIZERS ..............................................................37 -

THE THEOLOGY of POLITICAL POWER an Historical Approach to the Relationship Between Religion and Politics

THE THEOLOGY OF POLITICAL POWER An Historical Approach to the Relationship between Religion and Politics PART 2: RUSSIA AND THE WEST (to 1789) Vladimir Moss © Copyright: Vladimir Moss, 2011. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................4 IV. THE RUSSIAN AUTOCRACY: KIEV AND MOSCOW .............................5 Church and State in Kievan Rus’ ..........................................................................5 The Breakup of Kievan Rus’ ................................................................................11 Autocracy restored: St. Andrew of Bogolyubovo.................................................14 Russia between the Hammer and the Anvil ........................................................19 The Rise of Muscovy............................................................................................21 Russia and the Council ........................................................................................27 The Third Rome ...................................................................................................30 The Heresy of the Judaizers..................................................................................38 Possessors and Non-Possessors ...........................................................................46 St. Maximus the Greek ........................................................................................50 Ivan the Terrible: (1) The Orthodox Tsar............................................................52 -

On the Correlation Between the Concepts of Sin, Seduction, Temptation and Charm in Orthodox Anthropology

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 5 (2015 8) 912-918 ~ ~ ~ УДК 2:242 + 141.333 + 101.8 On the Correlation Between the Concepts of Sin, Seduction, Temptation and Charm in Orthodox Anthropology Elena V. Melnikova* Ural Federal University named after the B. N. Yeltsin 51 Lenin, Ekaterinburg, 620083, Russia Received 22.01.2015, received in revised form 16.02.2015, accepted 19.03.2015 The article attempts to carry out the philosophical reflection of anthropological theological perspective, placing the question of correlation of religious categories on a fundamentally different level, which exceeds the scope of the religious content. The notions of temptation, seduction and charm are compared. The designated categories are considered as the graduation of the same state, taken in development stages: from ethical neutrality, emotional non-involvement, expressed in the category of “temptation” through the emotional preparedness to respond to external stimuli, which is a test of the moral qualities of the person (“seduction”) to willingness to substitute the essence of good – sin (“charm”). Keywords: religion, religious studies, God, temptation, seduction, charm, sin, intention, soul, morals, ethics, penance, theology. Research area: philosophy. In the era of postmodernism and of spirit, self-determination in the face of God, postsecularism the interaction of religious and etc.) and to clarify the issue of the relationship non-religious of conceptual fields is particularly between different aspects of the “body” and important. Those categories that have traditionally “soul” in their modern sense. (Stepanova) been used only in the framework of theology Although the problem of man has been and, moreover, under the pressure of scientistic given an important place in theological thought, and atheistic attitudes, were expelled from other the special, deep and complete treatment of areas, acquire vernacular meaning today. -

The Wednesday Weekly

The Wednesday Weekly November 04, 2020 His Beatitude our Primate Marc with some of our monks and clergy in France Holy Presence Monastery at St. Dolay in France Our Lady of the Sign Church, St. Dolay, France 1 Monastery seen from the woods Monastery seen from the fields 1) Comments a) Father Leonard Hollands – History has far too many cases of ‘religious’ intolerance, persecution, and so-called ‘holy wars.’ The massacre of Christians continues today, and, sadly, probably always will. And, of course, the Church itself has been guilty of such ‘religious’ hatred. It is frightening to look at the history of the Church for that and many other reasons. We must make sure that we personally never allow religious or denominational prejudice to dwell in our hearts. There is no place for it in the Christian Faith as there is no place for class, cultural, racial, disability or any other kind of prejudice. Jesus’ bidding that we should love one another must not be watered down to loving just those who think, talk and behave like us. We are even to love our enemies! Our Lord certainly set the bar high for us! b) Mwrog Hermit – Bishop Paul, thank you so much for this week’s wonderful News: filled with inspirational and enlightening content! Duw bendith! God bless. 2) Recommended Reading – The Northern Thebaïd, Monastic Saints of the Russian North * The Solovetsky Monastery, founded in 1436, is a fortified monastery located on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea in northern Russia. It was one of the largest Christian citadels in northern Russia before it was converted into a Soviet prison and labor camp in 1926–39, and served as a prototype for the camps of the Gulag system. -

The Theophaneia School: Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism

The Theophaneia School: Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 08:05:26AM via free access Scrinium: Revue de patrologie, d’hagiographie critique et d’histoire ecclésiastique 3 Editorial Committee B. Lourié (Editor-in-Chief), St. Pétersbourg D. Nosnitsin (Secretary), Hamburg D. Kashtanov, Moscow S. Mikheev, Moscow A. Orlov, Milwaukee T. Senina, St. Pétersbourg D. Y. Shapira, Jérusalem S. Shoemaker, Oregon Secretariat T. Senina, St. Pétersbourg E. Bormotova, Montréal Scrinium. Revue de patrologie, d’hagiographie critique et d’histoire ecclésiastique, established in 2005, is an international multilingual scholarly series devoted to patristics, critical hagiography, and Church history. Each volume is dedicated to a theme in early church history, with a particular emphasis on Eastern Christianity, while not excluding developments in the western church. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 08:05:26AM via free access The Theophaneia School: Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism Edited by Basil Lourié Andrei Orlov 9 342009 Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 08:05:26AM via free access Gorgias Press LLC, 180 Centennial Ave., Piscataway, NJ, 08854, USA www.gorgiaspress.com Copyright © 2009 by Gorgias Press LLC Originally published in 2007 All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise without the prior written permission of Gorgias Press LLC. 2009 ܕ 9 ISBN 978-1-60724-083-9 ISSN 1817-7530 Scrinium 3 was originally published by Byzantinorossica, St. -

Mystics of the Christian Tradition

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen MYSTICS OF THE CHRISTIAN TRADITION From divine visions to self-tortures, some strange mystical experiences have shaped the Christian tradition as we know it. Full of colorful detail, Mystics of the Christian Tradition examines the mystical experiences that have determined the history of Christianity over two thousand years, and reveals the often sexual nature of these encounters with the divine. In this fascinating account, Fanning reveals how God’s direct revelation to St. Fran- cis of Assisi led to his living with lepers and kissing their sores, and describes the mystical life of Margery Kempe who “took weeping to new decibel levels.” Through presenting the lives of almost a hundred mystics, this broad survey invites us to consider what it means to be a mystic and to explore how people such as Joan of Arc had their lives deter- mined by divine visions. Mystics of the Christian Tradition is a comprehensive guide to discovering what mysticism means and who the mystics of the Christian tradition actually were. This lively and authoritative introduction to mysticism is a valuable survey for students and the general reader alike. Steven Fanning is Associate Professor of History at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is the author of A Bishop and His World Before the Gregorian Reform, Hubert of An- gers, 1006–1047 (1988), as well as almost a dozen articles on late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Mystics of the Christian Tradition 22 February 2001 09:18:47 Color profile: Disabled Composite -

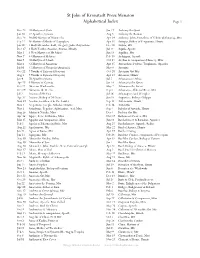

St John of Kronstadt Press Menaion Alphabetical Index Page 1

St John of Kronstadt Press Menaion Alphabetical Index Page 1 Dec 23 10 Martyrs of Crete Jan 17 Anthony the Great Jun 30 12 Apostles, Synaxis Aug 3 Anthony the Roman Dec 28 20,000 Martyrs of Nicomedia Apr 14 Anthony, John, Eustathius of Vilnius (Lithuania), Mtrs Sep 22 26 Martyred Monks of Zographou Apr 11 Antypas, Bishop of Pergamum, Hrmtr Jan 30 3 Holy Hierarchs: Basil, Gregory, John Chrysostom Dec 30 Anysia, Mtr Dec 17 3 Holy Youths (Ananias, Azarias, Misail) Jul 14 Aquila, Apostle May 1 3 New Martyrs of Mt Athos Jun 13 Aquilina, Mtr Nov 7 33 Martyrs of Melitene Feb 19 Archippus, Apostle Mar 9 40 Martyrs of Sebaste Oct 24 Arethas & companions (Homer), Mtrs Mar 6 42 Martyrs of Amorium Apr 15 Aristarchus, Pudens, Trophimus, Apostles Jul 10 45 Martyrs of Nicopolis (Armenia) May 8 Arsenius Oct 22 7 Youths of Ephesus (Sleepers) Oct 20 Artemius Grt Mtr Aug 4 7 Youths of Ephesus (Sleepers) Apr 13 Artemon, Hrmtr Jan 4 70 Apostles Synaxis Jul 5 Athanasius of Athos Apr 29 9 Martyrs of Cyzicus Jan 18 Athanasius the Great Oct 22 Abercius Wnderwrkr May 2 Athanasius the Great Oct 29 Abramius the Recluse Sep 5 Athanasius, Abbot of Brest, Mtr Jul 7 Acacius of Mt Sinai Jul 16 Athenogenes and Disciples Apr 17 Acacius, Bishop of Melitene Jun 15 Augustine, Bishop of Hippo Nov 29 Acacius, mentioned in The Ladder Sep 11 Autonomus, Hrmtr Nov 3 Acepsimus, Joseph, Aithalas, Hrmtrs Feb 14 Auxentius Nov 2 Acindynus, Pegasius, Aphthonius, et al, Mtrs Sep 4 Babylas of Antioch, Hrmtr Aug 26 Adrian & Natalia, Mtrs Dec 4 Barbara Grt Mtr Apr 16 Agape, Irene & Chionia, -

The Russian Orthodox Church As a Symbol of Right Order: a Voegelinian Analysis

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 The Russian Orthodox Church as a Symbol of Right Order: a Voegelinian Analysis. Lee David Trepanier Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Trepanier, Lee David, "The Russian Orthodox Church as a Symbol of Right Order: a Voegelinian Analysis." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Theology of Ritual and the Russian Old Rite: ‘The Art of Christian Living’

The Theology of Ritual and the Russian Old Rite: ‘The Art of Christian Living’ Submitted by Robert William Button to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Masters by Research in Theology and Religion in October 2015. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Robert William Button 1 Abstract This thesis is a study of the theology of ritual in the Russian Old Rite; in the characteristic worship and piety of the Russian Church prior to the Nikonian reforms in the mid-seventeenth century which led to the Great Schism in the Russian Church. In the context of the lifting of the anathemas against the Old Rite by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1971, this thesis sets out from the premise of the wholly Orthodox and salvific nature of the pre-Nikonian ritual and rite. It focusses on rite as not merely a specific mode of worship, but as a whole way of life, an existential-experiential phenomena, and it examines the notion of the ‘art of Christian living’ and the role of the rhythm of the ritual order in the synergistic striving for salvation. It argues that the ritualised and ordered Orthopraxis of the Old Rite represents, in principle, a translation of the notion of typikon or ustav into the life of the laity, and constitutes a hierotopic creativity with a distinctly salvific goal on both the collective and personal levels. -

Authority and Tradition in Contemporary Understandings of Hesychasm and the Jesus Prayer

Authority and Tradition in Contemporary Understandings of Hesychasm and the Jesus Prayer Christopher David Leonard Johnson Ph.D. The University of Edinburgh 2009 Abstract In today’s global religious landscape, many beliefs and practices have been dislocated and thrust into unfamiliar cultural environments and have been forced to adapt to these new settings. There has been a significant amount of research on this phenomenon as it appears in various contexts, much of it centred on the concepts of globalisation/localisation and appropriation. In this dissertation, the same process is explored in relation to the traditions of contemplative prayer from within Eastern Orthodox Christianity known as the Jesus Prayer and hesychasm. These prayer practices have traveled from a primarily monastic Orthodox Christian setting, into general Orthodox Christian usage, and finally into wider contemporary Western culture. As a result of this geographic shift from a local to a global setting, due mainly to immigration and dissemination of relevant texts, there has been a parallel shift of interpretation. This shift of interpretation involves the way the practices are understood in relation to general conceptions of authority and tradition. The present work attempts to explain the divergence of interpretations of these practices by reference to the major themes of authority and tradition, and to several secondary themes such as appropriation, cultural transmission, “glocalisation,” memory, and Orientalism. By looking at accounts of the Jesus Prayer and hesychasm from a variety of sources and perspectives, the contentious issues between accounts will be put into a wider perspective that considers fundamental differences in worldviews. ii Acknowledgments There have been countless friends and colleagues that have directly or indirectly aided me in the research and writing of this thesis.