Outside the Bottle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2230 Pine St. Redding

We know why high quality care means so very much. Since 1944, Mercy Medical Center Redding has been privileged to serve area physicians and their patients. We dedicate our work to continuing the healing ministry of Jesus in far Northern California by offering services that meet the needs of the community. We do this while adhering to the highest standards of patient safety, clinical quality and gracious service. Together with our more than 1700 employees and almost 500 volunteers, we offer advanced care and technology in a beautiful setting overlooking the City. Mercy Medical Center Redding is recognized for offering high quality patient care, locally. Designation as Blue Distinction Centers means these facilities’ overall experience and aggregate data met objective criteria established in collaboration with expert clinicians’ and leading professional organizations’ recommendations. Individual outcomes may vary. To find out which services are covered under your policy at any facilities, please contact your health plan. Mercy Heart Center | Mercy Regional Cancer Center | Center for Hip & Knee Replacement Mercy Wound Healing & Hyperbaric Medicine Center | Area’s designated Trauma Center | Family Health Center | Maternity Services/Center Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | Shasta Senior Nutrition Programs | Golden Umbrella | Home Health and Hospice | Patient Services Centers (Lab Draw Stations) 2175 Rosaline Ave. Redding, CA 96001 | 530.225.6000 | www.mercy.org Mercy is part of the Catholic Healthcare West North State ministry. Sister facilities in the North State are St. Elizabeth Community Hospital in Red Bluff and Mercy Medical Center Mt. Shasta in Mt. Shasta Welcome to the www.packersbay.com Shasta Lake area Clear, crisp air, superb fi shing, friendly people, beautiful scenery – these are just a few of the words used to describe the Shasta Lake area. -

California Regional Water Quality Control Board Central Valley Region

CALIFORNIA REGIONAL WATER QUALITY CONTROL BOARD CENTRAL VALLEY REGION MONITORING AND REPORTING PROGRAM NO. 5-01-233 FOR DANONE WATERS 6F NORTH AMERICA DANNONNATURAL SPRING WATERBOTTLING FACILITY SISKlYOU COUNTY EFFLUENT MONITORING The discharge of bottle rinse/floor wash w~tewater to the leachfield shatl b'e monitored as follows: Type of Sampling Parameter Units Sample Freg!!ency Flow gallons per day Flow meter Daily Specific Conductance f..Lmhos/cm Grab Weekly1 Total Dissolved Solids mg/1 Grab Weekly' pH units Grab Weekly' Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) mg/1 Grab Weekly' Total Coliform Organisms MPN/100 ml Grab Weekly' PrioritY Pollutants-Metals f..Lg/1 Grab Annually Priority Pollutants-Organics jlg/1 Grab Annually I The sampling frequency may be reduced to monthly after one year of sampling upon approval of the Executive Officer. GROUND WATER MONITORING Piezometers Each of the Piezometers within the leach field shall be monitored for depth to groundwater from the surface as follows: Type of Measurement Parameter Units measurement Frequency Depth beneath surface feet Visual Weekly --..,_ ' WASTE DISCHARGE REQUIREivfENTS ORDER NO. 5-01-233 -2- DAN ONE WATERS OF NORTH AMERICA NATURAL SPRING WATER BOTTLING FACILITY SISKIYOU COUNTY Monitoring Wells (MW-1, MW-2,.MW-3) Prior to sampling or purging, equilibrated groundwater elevations shall be measured to the nearest 0.01 foot. The wells shall be purged at least three well volumes until pH and electrical conductivity have stabilized. Sample co1lection shall follow standard analytical method protocols. -

Bottle Talk News Letter Subscriptions Continue to Grow Each Month

RALEIGH BOTTLE CLUB NEWS LETTER Editor: Marshall Clements MARCH, 2008 2008 BOTTLE CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT ____________________David Bunn VICE PRESIDENT ______________ Barton Weeks SECRETARY / TREASURER ______Robert Creech This extremely rare 1917 Pepsi lithograph by Rolf Armstrong is believed to be 'one of a kind.' It is from the collection of RBC member Sterling Mann. 1 THE RBC GALLERY THE The Colonial Grape Juice bottle shown above was made for the D. Pender Grocery Company. It was presented to the club by Robby Delius. The article below is from the web site groceteria.com. If you Show are interested in reading more about the evolvement from the neighborhood grocery to the large supermarket chains of today you might want to take a look at the web site. There are a lot of interesting pictures of early stores. Some of the pictures shown on the web site were provided by Robby. and tell David Pender, a native of Tarboro, N.C. came to Norfolk, Virginia in the 1890s, seeking his fortune, just as many young men who had left farms and small towns and traveled to cities in search of their future. Working in the retail grocery industry, Pender soon set out to establish his own store. That store was opened as the David Pender Grocery Company at the corner of Market Street and Monticello Avenue in Norfolk, Virginia in 1900. The store was a success, and Pender incorporated his company in January, 1901. Over the next 19 years the store prospered, offering the people of Norfolk the finest in groceries, meats and fresh produce. -

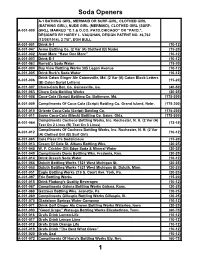

Soda Handbook

Soda Openers A-1 BATHING GIRL, MERMAID OR SURF-GIRL, CLOTHED GIRL (BATHING GIRL), NUDE GIRL (MERMAID), CLOTHED GIRL (SURF- A-001-000 GIRL), MARKED “C.T.& O.CO. PATD.CHICAGO” OR “PATD.”, DESIGNED BY HARRY L. VAUGHAN, DESIGN PATENT NO. 46,762 (12/08/1914), 2 7/8”, DON BULL A-001-001 Drink A-1 (10-12) A-001-047 Acme Bottling Co. (2 Var (A) Clothed (B) Nude) (15-20) A-001-002 Avon More “Have One More” (10-12) A-001-003 Drink B-1 (10-12) A-001-062 Barrett's Soda Water (15-20) A-001-004 Bay View Bottling Works 305 Logan Avenue (10-12) A-001-005 Drink Burk's Soda Water (10-12) Drink Caton Ginger Ale Catonsville, Md. (2 Var (A) Caton Block Letters A-001-006 (15-20) (B) Caton Script Letters) A-001-007 Chero-Cola Bot. Co. Gainesville, Ga. (40-50) A-001-063 Chero Cola Bottling Works (20-25) A-001-008 Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Baltimore, Md. (175-200) A-001-009 Compliments Of Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. Grand Island, Nebr. (175-200) A-001-010 Oriente Coca-Cola (Script) Bottling Co. (175-200) A-001-011 Sayre Coca-Cola (Block) Bottling Co. Sayre, Okla. (175-200) Compliments Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var (A) A-001-064 (12-15) Text On 2 Lines (B) Text On 3 Lines) Compliments Of Cocheco Bottling Works, Inc. Rochester, N. H. (2 Var A-001-012 (10-12) (A) Clothed Girl (B) Surf Girl) A-001-065 Cola Pleez It's Sodalicious (15-20) A-001-013 Cream Of Cola St. -

CAFFEINE? Department of Nutritional Services Brand Names Listed Are Not Intended to Be © 1986, Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, Endorsements of These Products

CAFFEINE CONTENT OF BEVERAGES, FOODS AND DRUGS Coffee Orange Soda 0 Drip, regular 106-164 mg/5 oz. Grape Soda 0 Percolated, regular 93-134 mg/5oz. Instant, regular 47-68 mg/5 oz. Non-prescription Drugs Decaffeinated 2-5 mg/5 oz. Stimulants (standard dose) Caffedrine capsules 200 mg Tea NoDoz Tablets 200 mg WHAT DO YOU 1 minute brew 21-33 mg/5oz. Vivarin Tablets 200 mg 3 minute brew 35-46 mg/5 oz. KNOW ABOUT 5 minute brew 39-50 mg/5 oz. Pain relievers (standard dose) Canned iced tea 22-36 mg/12 oz. Anacin Analgesic, Anacin Mix Strength, Anacin-3 64 mg Cocoa and Chocolate Cope 32 mg/tablet Cocoa Beverage Bufferin 0 (water mix) 2-8 mg/6 oz. Excedrin 130 mg Milk chocolate 6 mg/1 oz. Midol 64 mg Baking chocolate 35 mg/1 oz. Plain Aspirin, any brand 0 Sweet (dark) chocolate 20 mg/1 oz. Tylenol 0 Ovaltine 0 Vanquish 66 mg Postum 0 Diuretics (standard dose) Sodas mg/12 oz. can Aqua-Ban 200 mg Mr. Pibb, Diet 57 Fluidex 0 Mountain Dew 54 Permathene Water Off 200 mg Coca Cola, Diet Coke, Tab 45 Pre-Mens Forte 100 mg Shasta Cola, Regular and Diet 44 Mr. Pibb 41 Cold Remedies (standard dose) Dr. Pepper, Regular and Diet 40 Actifed 0 Pepsi Cola 38 Contac 0 Pepsi Light, Diet Pepsi 36 Comtrex 0 Diet Rite Cola 36 Coryban-D 30 mg Dristan 30 mg Royal Crown Cola 36 Royal Crown Cola, Diet 33 Neo-Synephrine Compounds 15 mg Cragmont Cola Trace Sudafed 0 7-up, Regular and Diet 0 Tr iaminicin 30 mg Sprite, Regular and Diet 0 Prescription Drugs Fanta 0 Cafergot Fresca 0 (migraine headaches) 100 mg/tablet Root Beer 0 Darvon Compound Club Soda 0 (pain reliever) 32 mg/tablet Ginger Ale 0 Fiorinal (headaches) 40 mg/tablet Tonic Water 0 Migrol (headaches) 50 mg/tablet CAFFEINE? Department of Nutritional Services Brand names listed are not intended to be © 1986, Kaiser Foundation Hospitals, endorsements of these products. -

Fueling the Bioeconomy

VOL. 3.1 Ford’s Legacy: FUELING THE BIOECONOMY “The fuel of the future…is going to come from fruit like that sumac out by the road, or from apples, weeds, sawdust – almost anything. There is fuel in every bit of vegetable matter that can be fermented.” –HENRY FORD, 1925 p11/ Cellulosic Biofuels Here at Last p27/ Aviation Biofuels on the Runway p33/ Wanted: Flex Fuel Vehicles PLUS Manipulating Extremophiles FROM BIO... TO FUEL JATROPHA: a newly engineered variety shows promise WHAT IS IT? however, has identified potentially WHAT’S NEXT? Jatropha is a hardy tropical plant whose high-yielding hybrid jatropha strains, Besides producing local jatropha name is derived from the Greek words combining years of intensive selective biodiesel, regions in some countries for “physician” and “nutrition.” Its breeding, high-throughput genotyping, are planting jatropha seeds for aviation leaves and seed pods are poisonous, but and agronomy. biofuel. One biofuel company has the plant has been used in medicines, deals in place to plant jatropha on mulch, and basket-weaving, made into WHERE DOES IT GROW? 250,000 acres in Brazil, India and organic fertilizer and rodent repellent, Originally from Central America, other countries that would produce an and as a cover crop to shelter other jatropha is most commonly found in estimated 70 million gallons of biofuel crops and prevent erosion. And inside Indonesia, the Philippines, Cambodia, a year. Jatropha can’t supply all the the pods are beans that can be crushed India, Mexico, and South America. fuel needed for aviation, since, as one and made into oil for soap, cosmetics, commentator has noted, the 1.6 billion lamps, and biofuels. -

Benzene Levels in Beverage Product Samples

Table 1: Benzene Levels in Beverage Product Samples FOUND, ppb PRODUCT METHOD METHOD 1 2 Products Safeway Select Diet Root Beer, lot 1 <1 Containing Safeway Select Diet Root Beer, lot 2 <1 Benzoate Safeway Select Diet Cola, lot 1 1.3 Only Safeway Select Diet Cola, lot 2 <1 Food Lion Caffeine Free Diet Cola with Splenda 1.1 Diet Dr. Pepper <1 Diet Coke Sweetened with Splenda <1 Diet Coke <1 Diet Pepsi, lot 1 <1 Diet Pepsi, lot 2 <1 Diet Rite Cola <1 A&W Root Beer n.d. Diet A&W Root Beer n.d. Dr. Pepper <1 Diet Cherry Vanilla Dr. Pepper <1 Diet Pepsi Lime n.d. Giant Diet Sun Pop Orange, lot 1 3.5 Giant Diet Sun Pop Orange, lot 2 <1 Giant Diet Sun Pop Orange, lot 3 n.d. Diet Sunkist Orange Soda, lot 1 <1 Diet Sunkist Orange Soda, lot 2 n.d. Faygo Creme Soda n.d. Faygo Orange <1 Sprite <1 Diet Sprite Zero n.d. Canada Dry Ginger Ale <1 Squirt Citrus Burst n.d. Diet Ruby Red Squirt Citrus Berry Burst n.d. Diet Rite Tangerine Soda n.d. Jones FuFu Berry Soda <1 Jones Sugar-Free Black Cherry Soda n.d. Canfield's Red Raspberry Sparkling Water Beverage n.d. <1 Fanta Orange n.d. Crush Orange <1 Safeway Select Clear Sugar Free Tropical Sparkling n.d. Water Nestea Cool Sweetened Lemon Iced Tea n.d. AquaCal Strawberry Flavored Water Beverage n.d. (reformulated) AquaCal Peach Mango Flavored Water Beverage n.d. (reformulated) American Fare Kiwi Strawberry Sparkling Water n.d. -

Bundaberg Ginger Beer, IZZE, Minute Maid Cherry Limeade Orig. & Light

The following beverages are NOT certified: Bundaberg Ginger Beer, IZZE, Minute Maid Cherry Limeade orig. & light, Dad’s Root Beer, Mike’s Hard Lemonade, Red Bull Cola, Snapple Fruit Punch, Monster Energy Drink, Kellogg’s Protein Water, Coke Products including Fanta bottled in Mexico, Hi-C Products in Cans, Bottles or Aseptic Packs. Additionally, this list is for fluid beverages only unless otherwise noted. There are many drink powders produced bearing commonly recognized names but are different formulations. Please Note: Reg. & diet are acceptable for any soda listed. This list is for soda produced and bottled in the USA only. 5- Hour Energy Drink - when bearing Star-K AHA - when bearing OU A&W - Cream Soda, Root Beer, Root Beer Ten, Root Beer w/ Aged Vanilla All Sport - when bearing OU America’s Choice - when bearing OU Aquafina (United States & Canada) Alive Enhance Water Sparkling - Black Cherry Dragonfruit, Lemon, Lemon Lime, Mango Pineapple, Orange Grapefruit, Peach Berry, Unsweetened Lemon, Unsweetened Lime, Unsweetened Raspberry, Unsweetened Strawberry, White Peach Apricot Arizona Iced Tea - when bearing OU Bai - when bearing OU Barq’s - French Vanilla Cream, Red Cream, Root Beer Ben & Jerry’s Milkshakes-when bearing KD (Dairy-non cholov yisroel) Cherry Garcia, Chocolate Fudge Brownie, Chunky Monkey Milkshake Big Red - Black Cherry, Blue, Cola, Lemon Lime, Orange, Peach, Pineapple, Red, Red Diet Caffeine free, Red Float, Root Beer Bubly Sparkling Water - Unsweetened Apple, Unsweetened Blackberry, Unsweetened Cherry, Unsweetened -

ENERGY DRINK CONTAINERS - Bottles & Cans by Cecil Munsey Copyright © 2006

52 Summer 2006 Bottles and Extras Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6 Fig. 7 Fig. 8 Fig. 9 Fig. 10 Fig. 11 Fig. 12 Fig. 13 Fig. 14 Fig. 15 Fig. 16 Fig. 17 Fig. 18 Fig. 19 Fig. 20 Fig. 21 Fig. 22 Fig. 23 Fig. 24 Fig. 25 Fig. 30 Fig. 31 Fig. 26 Fig. 27 Fig. 28 Fig. 29 Fig. 32 > < Fig. 33 Fig. 36 < Fig. 37 Fig. 35 Fig. 38 Fig. 34 > Bottles and Extras Summer 2006 53 ENERGY DRINK CONTAINERS - Bottles & Cans By Cecil Munsey Copyright © 2006 AUTHOR’S NOTE: This article can save you from making a mistake similar to one I made 35+ years ago. I look back now with melancholy at the time while completing the manuscript of my popular study of the Coca-Cola Company’s merchandising history – “The Illustrated Guide to the Collectibles of Cola” (Hawthorn Books, NY). – I consciously did not include a chapter on Coca- Cola cans. Why? I didn’t think that collectors would be interested in “rusty, old tin cans.” I overlooked the entire category except for a few of the early cone-top models and didn’t take into account the successful introduction of aluminum cans and bottles as attractive and long-lasting beverage containers. This article doesn’t make any such mistake; it glorifies a whole, relatively new, category of collectible containers, thus giving collectors the head-start information needed to begin a collection of energy drink cans and bottles. Thanks to eBay and other sources, the current beverages and even those products that didn’t make it in the fast- paced energy drink market, are still available. -

Caffeine: a Healthy Habit?

Amounts of Caffeine in Products TEA Instant/Brewed Tea (5 min. Brew) ...........................45 Caffeine: Instant Iced Tea (8 oz).............................................25 Food Milligrams Bottled Iced Teas (16 oz)................................. 15-100 A Healthy Habit? Snapple Iced Teas (16 oz)........................................42 DESSERTS/YOGURTS Green Tea ...............................................................30 Small chocolate bar....................................... up to 30 Celestial Seasonings Herbal (all).................................0 Coffee/cappuccino desserts and yogurts ..............8-85 Chocolate Brownie....................................................8 OTHER BEVERAGES Dark chocolate (1 oz)..............................................20 Hot Chocolate (8 oz).................................................5 Milk chocolate (1 oz) ................................................6 Chocolate flavored syrup (1 oz).................................4 COFFEE (6 oz) OVER THE COUNTER DRUGS ® Regular Brewed................................................60-175 Vivarin Tablets .....................................................200 ® Instant ...............................................................60-95 Dexatrim .............................................................200 ® Decaf Brewed.........................................................4.5 Nodoz .................................................................100 ® Instant Decaf.............................................................2 -

ENCORP PACIFIC (CANADA) Registered Brands

ENCORP PACIFIC (CANADA) Registered Brands 1 7 10 Cal Aquafina Plus Vitamins 7 select 10 YEARS OIL PATCH TOUGH LONGHORN 7 Select Café 100 Plus 7 UP 100PLUS 7 up Lemon 1181 7-Select 1818 Alberni 7-SELECT 7-Up 2 7-Up 2 Guys With Knives 7D Mango Nectar 2% 7SELECT 24 Hour Collision Center 7Select 24 Mantra Mango Juice 7SELECT Natural Spring Water 24K 7UP 27 North 7up 28 Black 7up Lemon Lemon Sparkling Lemonade 3 8 3 The Terraces Three 80 Degrees 33 Acres Of Heart 80 Degrees North 33 Acres of Mineral 33 Acres of Pacific 9 33 Acres of Sunrise 9 MM Energy Drink 365 A 365 Everyday Value A & W 365 Organic Lemonade A (Futura) 365 Organic Limeade A&W 365 Whole Foods Market A&W Apple Juice 4 A&W Orange Juice 49th Parallel Cascara A-Team Mortgages 49th Parallel Cold Brew A2Z Capital 49th Parallel Grocery Abbott Wealth Management 49th Parallel Iced Tea Aberfoyle Springs 49th Parallel Sparkling Green Tea Abhishek Mehta-MarforiGroup, Mr Home Inspector ABK Restoration Services 5 Abstract Creating Iconic Spaces 5 Hour Energy Abstract Developments 5 Hour Energy Acapulcoco 5 Hour Energy Extra Strength Accelerade 5-hour Energy Extra Strength Access Roadside Assistance 5-HOUR EXTRA STRENGTH Accompass 52 North Beverages Acme Analytical Laboratories Ltd. 52° North Acqua Di Aritzia 59th Street Food Co. Acqua Filette 6 Acqua Italia 6 Hour Power Acqua Panna 601 West Hastings ACTIVATE BALANCE - Fruit Punch ACTIVATE BEAUTY - Exotic Berry ACTIVATE CHARGED - Lemon Lime Wednesday, September 01, 2021 The General Identification Guidelines should be read along with this brand registry listing. -

Volume Grocery Chain in CCSW' S Territory

452 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION DECISIONS Initial Decision 118 FTC. IN THE MA TTER OF THE COCA-COLA BOTTLING COMPANY OF THE SOUTHWEST FINAL ORDER, OPINION, ETe. , IN REGARD TO ALLEGED VIOLATION OF SEe. 7 OF THE CLA YTON ACT AND SEe. 5 OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ACT Docket 9215, Complaint July 1988--Fina/ Order, lIug. , 1994 This final order requires Coca-Cola Bottling Company of the Southwest to divest within 12 months, the Dr Pepper franchise it acquired from San Antonio Dr Pepper Bottling. If the divestiture is not compJeted within that period, the Commission may appoint a trustee to complete it. In addition , the order re- quires the respondent to obtain Commission approval before acquiring any branded carbonated soft drink interests in any area in which it already makes distributes or sells branded concentrate or syrup, or branded carbonated soft drinks. Appearances For the Commission: James E. Elliott, Thomas B. Carter and Mary Lou Steptoe. For the respondent: Gregory Huffman , Thompson Knight Dallas, TX. INITIAL DECISION BY JAMES P. TIMONY. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE JUNE 14, 1991 BACKGROUND Companies and Persons 1. Respondent Coca-Cola Bottling Company of the Southwest CCSW" ) is a privately-held corporation with headquarters in San Antonio, Texas. (CX 980- U; RX 549-A.) Its sales in 1988 were $145,496 000. (CX 3806- * Complaint previously published 112 FTC 588 (1989). THE COCA COLA BOTTLING COMPANY OF THE SOUTHWEST 453 452 Initial Decision 2. In 1983 the Biedenharn family consolidated their holdings in Temple, Uvalde and San Antonio Coca-Cola Bottling Companies into CCSW, and established The Biedenharn Corporation to hold the stock of CCSW.