The Octant (Edited from Wikipedia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 03:43:06AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

'The Early Development of the Davis Quadrant', In: Bulletin of The

The Early Development of the Davis Quadrant Nicolàs de Hilster Introduction Observation Methods By the end of the 17th century one of the According to Atkinson the ‘... Instrument is most popular instruments for taking alti- rarely used otherwise than to observe the tudes of the sun was the Davis quadrant Sun’s Meridian Altitude...’.4 The alternate (Fig. 1), of which it is generally accepted use Atkinson referred to was perhaps the that it was fully developed by 1604.1 Over determination of longitude by lunar dis- the years during my research of early navi- tance as described in a work printed for J. gational instruments I found clues showing Wilford in 1726.5 For measuring the sun’s that 1604 was the start of its development meridian altitude the shadow vane was set rather than the end. The development went at a whole number of degrees, some 15-20 through several stages, relating to the frame, degrees lower than the expected zenith dis- the scales and the vanes. In addition to that tance of the meridian passage of the sun. also the name of the instrument changed While standing with his back towards the over time, not becoming ‘Davis quadrant’ sun – instruments used in this way were until the last quarter of the 17th century. henceforth given the general name ‘back- This article deals with the early develop- staff’ – the observer would align the slit in ment of the instrument and tries to provide the horizon vane with the horizon, while evidence that the instrument was not fully trying to coincide it with the upper edge of developed until the 1670s. -

The Spiegelboog (Mirror-Staff): a Reconstruction

The Spiegelboog (mirror-staff): a reconstruction N. de Hilster Introduction might lead to confusion in this article. I will The upper vane on the cross is called ‘shad- At the end of the 16th century one of the therefore refer to the instrument John Da- ow-vane’, the lower one ‘sight-vane’. They th principal instruments for celestial naviga- vis invented as back-staff and to the 17 had fixed positions, enforced by brass pins, tion at sea was the cross-staff (Fig. 1 A. The century development as Davis Quadrant. by which they can be pre-set at three differ- ent distances symmetrically from the staff others were the mariner’s astrolabe and The main difference between the hoek- the quadrant, but thanks to its accuracy along the cross. The sliding horizon-vane boog and the Davis Quadrant was that the could then be used with or without the (and price compared to the astrolabe) the scales on a hoekboog were engraved on cross-staff would eventually replace both mirror for backward observations. Without chords while on a Davis Quadrant they the mirror the shadow of the shadow-vane instruments. The cross-staff is a wooden were engraved on circle segments. Usu- instrument consisting of a square staff and was cast onto the horizon-vane, which had ally the smaller chord of the hoekboog was a rectangular hole through which the hori- up to four sliding transoms or vanes. For engraved in 10 degrees intervals while the each vane a scale was engraved on one of zon was seen. -

Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 04:24:08PM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

“Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 05:14:25AM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

Hadley's Octant (A. D. 1731)

HADLEY’S OCTANT (A. D. 1731). On the occasion of the second centenary of the invention of reflecting instruments and in accordance with the usual custom of reproducing in the Hydrographic Review documents of particular interest connected with the history of nautical and hydrographic science, the communication made by John Hadley to the Royal Society of London on 13th May, 1731, is repro duced hereafter in facsimile. This communication was published in N° 420 of the Philosophical Transactions. It appears that the oldest document in which allusion is made to the principle of reflection by plane mirrors, as applied to the measurement of angles, is the History of the Royal Society of London by B ir c h . In this book, under the date of 22nd August, 1666, it is stated “ Mr. H o o k mentionned a new astronomical instrument for making observations of distances by reflection”. In another place it may be read that on the 29th August of the same year, H o o k spoke of this instrument again, it being then under construction, to the members of the Society. They invited him to submit it as soon as possible and this was done on 12th September of that year. The instrument submitted by H o o k differed in important details from the modern sextant; it was provided with but one mirror and thus was a single reflecting instrument. This was the fundamental defect which made it impos sible for H o o k ’s invention to be a success. However, the idea of using reflection from a plane mirror for the measu rement of angles was not forgotten and, in spite of H o o k ’s want of success the principle was taken up by others who sought to correct the disadvantages of the instrument as first invented. -

“Navigational and Nautical Equipment”

“NAVIGATIONAL AND NAUTICAL EQUIPMENT” ΑΚΑΓΗΜΙΑΔΜΠΟΡΙΚΟΤΝΑΤΣΙΚΟΤ Α.Δ.Ν. ΜΑΚΔΓΟΝΙΑ ΔΠΙΒΛΔΠΩΝ ΚΑΘΗΓΗΣΡΙΑ: ΠΑΝΑΓΟΠΟΤΛΟΤ ΜΑΡΙΑ ΘΔΜΑ: NAVIGATIONAL AND NAUTICAL EQUIPMENT ΣΗ ΠΟΤΓΑΣΡΙΑ: ΚΔΠΔΣΑΡΗ ΙΩΑΝΝΑ Α.Γ.Μ: 3432 Ημεπομηνία ανάληψηρ ηηρ επγαζίαρ: Ημεπομηνία παπάδοζηρ ηηρ επγαζίαρ: Α/Α Ονομαηεπώνςμο Διδικόηηρ Αξιολόγηζη Τπογπαθή 1 2 3 ΣΔΛΙΚΗ ΑΞΙΟΛΟΓΗΗ Ο ΓΙΔΤΘΤΝΣΗ ΥΟΛΗ : Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1 - Charts and drafting instruments .................................................................. 5 1.1 Nautical chart ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1.1 Chart correction ............................................................................................. 7 Limitations .............................................................................................................. 7 1.1.2 Map projection, positions, and bearings ........................................................ 8 1.1.3 Electronic and paper charts ............................................................................ 9 Labeling nautical charts .......................................................................................... 9 1.1.4 Details on a nautical chart ........................................................................... 10 Pilotage information ............................................................................................ -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13. -

The Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Wish You a Very Happy Christmas and a Prosperous New Year News and Events Odette Buchanan, Friends’ Secretary

The Newsletter of the Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre Issue Number 12: November 2008 £2.00; free to members Christmas Number and Special issue to mark the 90th Anniversary of the World War One Armistice In memory of Frederick Charles Wellard, grandfather of the new FOMA Membership Secretary, Betty Cole. The wooden cross, pictured, is a rare image of how the war graves appeared before their replacement by the now familiar rows of white stone. Frederick was killed at Arras, France, in August 1917. The front line diary records, ‘16/8/17 Normal trench routine. Trenches deepened where necessary. Enemy active with pineapples. S. Major Wellard killed. C.Q.M.S. Blackstock wounded (afterwards died).’ Three days later the battalion was relieved. Fred left a widow and five young children, three of whom, including Betty’s mother, Ivy, were sent to orphanages. More of Frederick’s story can be read inside. The Friends of Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre wish you a very happy Christmas and a prosperous New Year News and Events Odette Buchanan, Friends’ Secretary At the 2008 FOMA AGM, it was decided that members should take on all the clerical responsibilities of the organisation, especially as we are all over the age of consent (some more so than others). In a moment of mental aberration I agreed to take on the role of Secretary. Aeons ago I had been paid to be the secretary to the Overseas Sales Director of a multi-national company and had had recent voluntary secretarial experience with another Friends group which I helped found. -

James Short and John Harrison: Personal Genius and Public Knowledge

Science Museum Group Journal James Short and John Harrison: personal genius and public knowledge Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Jim Bennett 10-09-2014 Cite as 10.15180; 140209 Research James Short and John Harrison: personal genius and public knowledge Published in Autumn 2014, Issue 02 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/140209 Abstract The instrument maker James Short, whose output was exclusively reflecting telescopes, was a sustained and consistent supporter of the clock and watch maker John Harrison. Short’s specialism placed his work in a tradition that derived from Newton’s Opticks, where the natural philosopher or mathematician might engage in the mechanical process of making mirrors, and a number of prominent astronomers followed this example in the eighteenth century. However, it proved difficult, if not impossible, to capture and communicate in words the manual skills they had acquired. Harrison’s biography has similarities with Short’s but, although he was well received and encouraged in London, unlike Short his mechanical practice did not place him at the centre of the astronomers’ agenda. Harrison became a small part of the growing public interest in experimental demonstration and display, and his timekeepers became objects of exhibition and resort. Lacking formal training, he himself came to be seen as a naive or intuitive mechanic, possessed of an individual and natural ‘genius’ for his work – an idea likely to be favoured by Short and his circle, and appropriate to Short’s intellectual roots in Edinburgh. The problem of capturing and communicating Harrison’s skill became acute once he was a serious candidate for a longitude award and was the burden of the specially appointed ‘Commissioners for the Discovery of Mr Harrison’s Watch’, whose members included Short. -

Defending Scilly

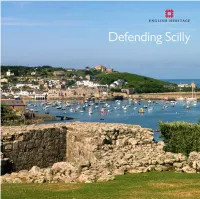

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England

The Ingenious Mr Dummer: Rationalizing the Royal Navy in Late Seventeenth-Century England Celina Fox In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Royal Navy constituted by far the greatest enterprise in the country. Naval operations in and around the royal dockyards dwarfed civilian industries on account of the capital investment required, running costs incurred and logistical problems encountered. Like most state services, the Navy was not famed as a model of efficiency and innovation. Its day-to-day running was in the hands of the Navy Board, while a small Admiralty Board secretariat dealt with discipline and strategy. The Navy Board was responsible for the industrial organization of the Navy including the six royal dockyards; the design, construction and repair of ships; and the supply of naval stores. In practice its systems more or less worked, although they were heavily dependent on personal relationships and there were endless opportunities for confusion, delay and corruption. The Surveyor of the Navy, invariably a former shipwright and supposedly responsible for the construction and maintenance of all the ships and dockyards, should have acted as a coordinator but rarely did so. The labour force worked mainly on day rates and so had no incentive to be efficient, although a certain esprit de corps could be relied upon in emergencies.1 It was long assumed that an English shipwright of the period learnt his art of building and repairing ships primarily through practical training and experience gained on an apprenticeship, in contrast to French naval architects whose education was grounded on science, above all, mathematics.