Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15

Library of Congress Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15 Cutting Marsh (From photograph loaned by John N. Davidson.) Wisconsin State historical society. COLLECTIONS OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY. OF WISCONSIN EDITED AND ANNOTATED BY REUBEN GOLD THWAITES Secretary and Superintendent of the Society VOL. XV Published by Authority of Law MADISON DEMOCRAT PRINTING COMPANY, STATE PRINTER 1900 LC F576 .W81 2d set The Editor, both for the Society and for himself, disclaims responsibility for any statement made either in the historical documents published herein, or in articles contributed to this volume. 1036011 18 N43 LC CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS. Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Volume 15 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.7689d Library of Congress THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SERIAL RECORD NOV 22 1943 Copy 2 Page. Cutting Marsh Frontispiece. Officers of the Society, 1900 v Preface vii Some Wisconsin Indian Conveyances, 1793–1836. Introduction The Editor 1 Illustrative Documents: Land Cessions—To Dominique Ducharme, 1; to Jacob Franks, 3; to Stockbridge and Brothertown Indians, 6; to Charles Grignon, 19. Milling Sites—At Wisconsin River Rapids, 9; at Little Chute, 11; at Doty's Island, 14; on west shore of Green Bay, 16; on Waubunkeesippe River, 18. Miscellaneous—Contract to build a house, 4; treaty with Oneidas, 20. Illustrations: Totems—Accompanying Indian signatures, 2, 3, 4. Sketch of Cutting Marsh. John E. Chapin, D. D. 25 Documents Relating to the Stockbridge Mission, 1825–48. Notes by William Ward Wight and The Editor. 39 Illustrative Documents: Grant—Of Statesburg mission site, 39. Letters — Jesse Miner to Stockbridges, 41; Jeremiah Evarts to Miner, 43; [Augustus T. -

Trailblazing Native Journalist Paul Demain to Speak in Skokie November 10 for Mitchell Museum Event

Mitchell Museum of the American Indian Press contact: Nat Silverman 3001 Central Street. Nathan J. Silverman Co. Evanston, IL 60201 1830 Sherman Ave., Suite 401 (847) 475-1030 Evanston, IL 60201-3774 www.mitchellmuseum.org Phone (847) 328-4292 Fax (847) 328-4317 Email: [email protected] News For Approval Attn: Arts & Entertainment/Lectures Trailblazing Native Journalist Paul DeMain to Speak in Skokie November 10 for Mitchell Museum Event Award-Winning Investigative Reporter Will Analyze Power of Native Voters in National and State Elections Editor of ‘News from Indian Country’ to Deliver Museum’s Annual Montezuma Lecture EVANSTON, Ill., October 25, 2012 — American Indian journalist, entrepreneur, and political activist Paul DeMain of Hayward, Wis., will discuss what he sees as Native America’s growing impact on national and local politics and public policy at a lecture organized by the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian, to be held at 3:30 p.m. on Saturday, November 10, in the Petty Auditorium of the Skokie Public Library, 5215 Oakton Street, Skokie, Ill. An award-winning investigative reporter of Oneida and Ojibwe descent, DeMain will deliver the Mitchell Museum’s third annual Dr. Carlos Montezuma Honorary Lecture. The title of his talk is “American Indians and the Tipping Point: No Longer a Miner’s Canary.” “Native America has a bigger seat at all the tables now,” DeMain said in a telephone interview with the Mitchell Museum. “Tribes are something to be reckoned with.” In some states, counties, and districts, Native votes can determine the outcome of close elections, he said. DeMain said he can recall when political campaigns used to ignore Indian reservations. -

A NATIONAL MUSEUM of the Summer 2000 Celebrating Native

AmencanA NATIONAL MUSEUM of the Indiant ~ti • Summer 2000 Celebrating Native Traditions & Communities INDIAN JOURNALISM • THE JOHN WAYNE CLY STORY • COYOTE ON THE POWWOW TRAIL t 1 Smithsonian ^ National Museum of the American Indian DAVID S AIT Y JEWELRY 3s P I! t£ ' A A :% .p^i t* A LJ The largest and bestfôfltikfyi of Native American jewelry in the country, somçjmhem museum quality, featuring never-before-seen immrpieces of Hopi, Zuni and Navajo amsans. This collection has been featured in every major media including Vogue, Elle, Glamour, rr_ Harper’s Bazaar, Mirabella, •f Arnica, Mademoiselle, W V> Smithsonian Magazine, SHBSF - Th'NwYork N ± 1R6%V DIScbuNTDISCOUNT ^ WC ^ 450 Park Ave >XW\0 MEMBERS------------- AND television stations (bet. 56th/57th Sts) ' SUPPORTERS OF THE nationwide. 212.223.8125 NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE © CONTENTS Volume 1, Number 3, Summer 2000 10 Read\ tor Pa^JG One -MarkTrahantdescribeshowIndianjoumalistsHkeMattKelley, Kara Briggs, and Jodi Rave make a difference in today's newsrooms. Trahant says today's Native journalists build on the tradition of storytelling that began with Elias Boudinot, founder of the 19th century newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. 1 ^ WOVCn I hrOU^h Slone - Ben Winton describes how a man from Bolivia uses stone to connect with Seneca people in upstate New York. Stone has spiritual and utilitarian significance to indigeneous cultures across the Western Hemisphere. Roberto Ysais photographs Jose Montano and people from the Tonawanda Seneca Nation as they meet in upstate New York to build an apacheta, a Qulla cultural icon. 18 1 tie John Wayne Gly Story - John Wayne Cly's dream came true when he found his family after more than 40 years of separation. -

A Case Study of Oneida Resilience and Corn

Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development ISSN: 2152-0801 online https://www.foodsystemsjournal.org Kaˀtshatstʌ́ sla: “Strength of belief and Special JAFSCD Issue Indigenous Food Sovereignty in North America vision as a people”—A case study of sponsored by Oneida resilience and corn Lois L. Stevens a * and Joseph P. Brewer II b University of Kansas Submitted February 13, 2019 / Revised April 3 and June 3, 2019 / Accepted June 4, 2019 / Published online December 20, 2019 Citation: Stevens, L. L., & Brewer, J. P., II. (2019). Kaˀtshatstʌ́sla: “Strength of belief and vision as a people”—A case study of Oneida resilience and corn. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 9(Suppl. 2), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2019.09B.015 Copyright © 2019 by the Authors. Published by the Lyson Center for Civic Agriculture and Food Systems. Open access under CC-BY license. Abstract community has been geographically divided from The collective nations of the Haudenosaunee are all other Haudenosaunee nations, and even from governed by their shared ancestral knowledge of its members own Oneida kin, for nearly 200 years; creation. This storied knowledge tells of an intellec- however, this community was able to re-establish tual relationship with corn that has been cultivated its relationship with corn after years of disconnect. by the Haudenosaunee through generations and Oneida Nation community-driven projects in represents core values that are built into commu- Wisconsin have reshaped and enhanced the con- nity resilience, for the benefit of future generations. nection to corn, which places them at the forefront The Oneida, members of the Haudenosaunee Con- of the Indigenous food sovereignty movement. -

June 12, 2003 Official Newspaper of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin

KalihwisaksKalihwisaks “She Looks For News” June 12, 2003 Official Newspaper of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin www.oneidanation.org New health center is grand by Phil Wisneski dedication of many people art facility,” she said. “Finally!” That was the over the years, the fruition of Danforth also added that overwhelming response from a new health care facility had the number of patients that the community as the Oneida finally become a reality. are registered at the new facil- Community Health Center Oneida Chairwoman Tina ity exceeds 20,000. held it’s grand opening on Danforth, a former employee The new facility located at June 6. of the old health center, was on the corner of Airport Road Over a decade in the mak- filled with excitement. “This and Overland Road dwarfs ing, the brand new, 65,000 is a project the entire commu- the former site, which had square feet, the largest Indian nity can be proud of. We have only 22,850 square feet. The health care facility in the state always considered health care new site also houses all the formally welcomed commu- a priority and with the open- medical needs of the commu- nity members, local leaders ing of this new facility we can See Page 2 Photo by Phil Wisneski and others through it’s doors. continue to serve community Oneida Business Committee members and Health Center dignitaries cut the rib- With the hard work and members in this state of the Health Center bon at the grand opening of the 65,000 foot new health care facility Ho-Chunk Doyle, Potawatomi agree Nation proposes HatsHats ofofff toto graduatesgraduates large casino to changes in compact MILWAUKEE (AP) - Gov. -

Wisconsin Magazine of History

. .•:,.•,:.•!.«,.V,^",'-:,:,.V..?;V-"X';''- Wisconsin Magazine of History Theobald Otjcn and the United States 'Njivy CHARLES E. TWINING A Mission to the Menominee: Part Four ALFRED COPE E. A. Ross: The Progressive As Nativist .JULIUS WEINBERG A German's Letter From Territorial Wisconsin Edited by JACK j. DETZLER Published by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin / Vol. 50, No. 3 / Spring, 1967 THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN LESLIE H. FISHEL, JR., Director Officers SCOTT M. CUTLIP, President HERBERT V. KOHLER, Honorary Vice-President JOHN C. GEILFUSS, First Vice-President E. E. HOMSTAD, Treasurer CLIFFORD D. SWANSON, Second Vice-President LESLIE H. FISHEL, JR., Secretary Board of Curators Ex-Officio WARREN P. KNOWLES, Governor of the State MRS. DENA A. SMITH, State Treasurer ROBERT C. ZIMMERMAN, Secretary of State FRED H. HARRINGTON, President of the University WILLIAM C. KAHL, Superintendent of Public Instruction MRS. WILLIAM H. L. SMYTHE, President of the Women's Auxiliary Term Expires, 1967 THO.MAS H. BARLAND E. E. HOMSTAD MRS. RAYMOND J. KOLTES F. HARWOOD ORBISON Eau Claire Black River Falls Madison Appleton M. J. DYRUD MRS. CHARLES B. JACKSON CHARLES R. MCCALLUM DONALD C. SLIGHTER Prairie Du Chien Nashotah Hubertus Milwaukee JIM DAN HILL MRS. VINCENT W. KOCH FREDERICK I. OLSON DR. LOUIS C. SMITH Middleton Janesville Wauwatosa Lancaster Term Expires, 1968 GEORGE BANTA, JR. MRS. HENRY BALDWIN WILLIAM F. STARK CEDRIC A. VIG Menasha Wisconsin Rapids Pewaukee Rhinelander H. M. BENSTEAD ROBERT B. L. MURPHY MILO K. SWANTON CLARK WILKINSON Racine Madison Madison Baraboo KENNETH W. HAAGENSEN FREDERIC E. RISSER FREDERICK N. TROWBRIDGE STEVEN P. -

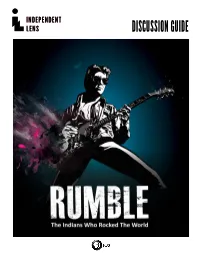

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents Using This Guide 3

DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents Using This Guide 3 Indie Lens Pop-Up We Are All Neighbors Theme 4 About the Film 5 From the Filmmakers 6 Artist Profiles 8 Background Information 13 What is Indigenous Music? 13 Exclusion and Expulsion 14 Music and Cultural Resilience 15 The Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee 16 Native and African American Alliances 17 Discussion 18 Conversation Starter 18 Post-Screening Discussion Questions 19 Engagement Ideas 20 Potential Partners and Speakers 20 Activities Beyond a Panel 21 Additional Resources 22 Credits 23 DISCUSSION GUIDE RUMBLE: THE INDIANS WHO ROCKED THE WORLD 2 USING THIS GUIDE This discussion guide is a resource to support organizations hosting Indie Lens Pop-Up events for the film RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World. Developed primarily for facilitators, this guide offers background information and engagement strategies designed to raise awareness and foster dialogue about the integral part Native Americans have played in the evolution of popular music. Viewers of the film can use this guide to think more deeply about the discussion started in RUMBLE and find ways to participate in the national conversation. RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World is an invitation to come together with neighbors and pay tribute to Native influences on America’s most celebrated music. The film makes its PBS broadcast premiere on the Independent Lens series on January 21, 2019. Indie Lens Pop-Up is a neighborhood series that brings people together for film screenings and community-driven conversations. Featuring documentaries seen on PBS’s Independent Lens, Indie Lens Pop-Up draws local residents, leaders, and organizations together to discuss what matters most, from newsworthy topics to family and relationships. -

A Report on the Case of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash

A Report on the Case of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash By: [email protected] February 2004 • Statements from AIM, Peltier, NYM & Graham Defense Committee • Excerpt from Agents of Repression Contents Report on the Case of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash Update & Background________________________________________ 2 Counter-Insurgency & COINTELPRO__________________________ 3 Once Were Warriors? AIM____________________________________ 5 FBI Version of Events_________________________________________ 6 Trial of Arlo Looking Cloud ___________________________________ 7 John Graham’s Version of Events_______________________________8 Position on Death of Anna Mae Aquash__________________________ 9 Position on Informants & Collaborators_________________________ 10 Conclusion__________________________________________________ 11 Statements AIM Colorado, April 3/03______________________________________12 Peltier on Graham Arrest Dec. 5/03_____________________________ 13 NYM on Graham, Feb. 7/04____________________________________ 14 Peltier on Kamook Banks, Feb. 10/04____________________________ 15 Graham Defense on Looking Cloud Trial, Feb. 9/04________________16 Peltier Lawyer on Looking Cloud Trial, Feb. 7/04__________________18 Excerpt: Agents of Repression, Chapter 7_________________________20 ________________________________________________________________________ For Info, contact: • freepeltier.org • grahamdefense.org ________________________________________________________________________ Note: Organizers should 3-hole punch this document and place in binder -

Anton Treuer Vitae

BOOKS The Language Warrior’s Manifesto: How to Keep Our Languages Alive No Matter the Odds Anton Treuer The Indian Wars: Battles, Bloodshed & the Fight for Freedom on the American Frontier Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask Author • Speaker • Trainer • Professor Warrior Nation: A History of the Red Lake Ojibwe Ojibwe in Minnesota The Assassination of Hole in the Day Living Our Language: Ojibwe Tales & Oral Histories Atlas of Indian Nations Mino-doodaading: Dibaajimowinan Ji-mino-ayaang Awesiinyensag: Dibaajimowinan Ji-gikinoo’amaageng Naadamaading: Dibaajomiwinan Ji-nisidotaading Ezhichigeng: Ojibwe Word List Wiijikiiwending Aaniin Ekidong: Ojibwe Vocabulary Project Omaa Akiing Akawe Niwii-tibaajim Nishiimeyinaanig Anooj Inaajimod Indian Nations of North America 40+ AWARDS & FELLOWSHIPS, INCLUDING American Philosophical Society National Endowment for the Humanities National Science Foundation Bush Foundation John Simon Guggenheim Foundation WORK Professor of Ojibwe, Bemidji State University, 8/2000-present Executive Director, American Indian Resource Center, Bemidji State University, 11/2012- 7/2015 Editor, Oshkaabewis Native Journal, Bemidji State University, 3/1995-present Assistant Professor of History, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 8/1996-6/2001 Anton Treuer (pronounced troy-er) is Professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji PRESENTATION EXPERIENCE State University and author of 19 Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask books. His equity, education, and Cultural Competence & Equity cultural work has put him on a path Strategies for Addressing the Achievement Gap of service around the region, the Tribal Sovereignty & History nation, and the world. Ojibwe Language & Culture EDUCATION http://antontreuer.com Ph.D.: History, University of Minnesota, 1997 B.A. -

Journalism in Indian Country: Story Telling That Makes Sense

The Howard Journal of Communications, 21:328–344, 2010 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1064-6175 print=1096-4649 online DOI: 10.1080/10646175.2010.519590 Journalism in Indian Country: Story Telling That Makes Sense SHARON M. MURPHY Emeritus Professor, Department of Communication, Bradley University, Peoria, Illinois, USA Despite its importance, Native American journalism is rarely included in histories of Native peoples or in most histories and analyses of American journalism. This article applies Carey’s theory of journalism as a state of consciousness to Native American jour- nalism. It explores approaches early Native American journalists took to apprehending and experiencing the cataclysmic changes taking place in their worlds, establishing written identities for their own communities and among their non-Indian neighbors, and adopting and adapting accepted conventions of American journal- ism. Further, it examines current Native media that work in and expand on the traditions that began in the early 19th century and amid some of the same challenges experienced then. KEYTERMS American Indian media, Elias Boudinot, Native American journalism, native broadcast, native story telling, tra- ditional cultures Over 180 years ago, community journalism among American Indians began in what is now Calhoun County, Georgia. The bilingual Cherokee Phoenix, printed in English and Cherokee, was the first regular newspaper published by Indian people, about Indian people, and for Indian people, as well as for a readership that stretched as far as London. During the succeeding 18 dec- ades of print, then electronic, and ultimately web-based media, reservation and urban journalists have used the press in building and reflecting on com- munity, championing Native American rights, correcting mistakes and misin- terpretations by mainstream media and preserving important traditions in Indian Country.1 Address correspondence to Dr. -

Peace, Power and Persistence: Presidents, Indians, and Protestant Missions in the American Midwest 1790-1860

PEACE, POWER AND PERSISTENCE: PRESIDENTS, INDIANS, AND PROTESTANT MISSIONS IN THE AMERICAN MIDWEST 1790-1860 By Rebecca Lynn Nutt A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History—Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT PEACE, POWER AND PERSISTENCE: PRESIDENTS, INDIANS, AND PROTESTANT MISSIONS IN THE AMERICAN MIDWEST 1790-1860 By Rebecca Lynn Nutt This dissertation explores the relationships between the Shawnee and Wyandot peoples in the Ohio River Valley and the Quaker and Methodist missionaries with whom they worked. Both of these Indian communities persisted in the Ohio Valley, in part, by the selective adoption of particular Euro-American farming techniques and educational methods as a means of keeping peace and remaining on their Ohio lands. The early years of Ohio statehood reveal a vibrant, active multi-cultural environment characterized by mutual exchange between these Indian nations, American missionaries, and Euro- and African-American settlers in the frontier-like environment of west-central Ohio. In particular, the relationships between the Wyandot and the Shawnee and their missionary friends continued from their time in the Ohio Valley through their removal to Indian Territory in Kansas in 1833 and 1843. While the relationships continued in the West, the missions themselves took on a different dynamic. The teaching methods became stricter, the instruction observed religious teaching more intensely, and the students primarily boarded at the school. The missionary schools began to more closely resemble the notorious government boarding schools of the late-nineteenth century as the missions became more and more entwined with the federal government.