DISCUSSION GUIDE Table of Contents Using This Guide 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock and Roll Rockandrollismyaddiction.Wordpress.Com

The Band, Ten Years After , Keef Hartley Band , Doris Troy, John Lennon ,George Harrison, Leslie West, Grant Green, Eagles, Paul Pena, Bruce Springsteen, Peter Green, Rory Gallagher, Stephen Stills, KGB, Fenton Robinson, Jesse “Ed” Davis, Chicken Shack, Alan Haynes,Stone The Crows, Buffalo Springfield, Jimmy Johnson Band, The Outlaws, Jerry Lee Lewis, The Byrds , Willie Dixon, Free, Herbie Mann, Grateful Dead, Buddy Guy & Junior Wells, Colosseum, Bo Diddley, Taste Iron Butterfly, Buddy Miles, Nirvana, Grand Funk Railroad, Jimi Hendrix, The Allman Brothers, Delaney & Bonnie & Friends Rolling Stones , Pink Floyd, J.J. Cale, Doors, Jefferson Airplane, Humble Pie, Otis Spann Freddie King, Mike Fleetwood Mac, Aretha Bloomfield, Al Kooper Franklin , ZZ Top, Steve Stills, Johnny Cash The Charlie Daniels Band Wilson Pickett, Scorpions Black Sabbath, Iron Butterfly, Buddy Bachman-Turner Overdrive Miles, Nirvana, Son Seals, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton John Mayall, Neil Young Cream, Elliott Murphy, Años Creedence Clearwater Bob Dylan Thin Lizzy Albert King 2 Deep Purple B.B. King Años Blodwyn Pig The Faces De Rock And Roll rockandrollismyaddiction.wordpress.com 1 2012 - 2013 Cuando decidimos dedicar varios meses de nuestras vidas a escribir este segundo libro recopilatorio de más de 100 páginas, en realidad no pensamos que tendríamos que dar las gracias a tantas personas. En primer lugar, es de justicia que agradezcamos a toda la gente que sigue nuestro blog, la paciencia que han tenido con nosotros a lo largo de estos dos años. En segundo lugar, agradecer a todos los que en determinados momentos nos han criticado, ya que de ellas se aprende. Quizás, en ocasiones pecamos de pasión desmedida por un arte al que llaman rock and roll. -

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Office of Diversity Presents

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Office of Diversity presents Friday Film Series 2012-2013: Exploring Social Justice Through Film All films begin at 12:00 pm on the Chicago campus. Due to the length of most features, we begin promptly at noon! All films screened in Daniel Hale Williams Auditorium, McGaw Pavilion. Lunch provided for attendees. September 14 – Reel Injun by Neil Diamond (Cree) http://www.reelinjunthemovie.com/site/ Reel Injun is an entertaining and insightful look at the Hollywood Indian, exploring the portrayal of North American Natives through a century of cinema. Travelling through the heartland of America and into the Canadian North, Cree filmmaker Neil Diamond looks at how the myth of “the Injun” has influenced the world’s understanding – and misunderstanding – of Natives. With clips from hundreds of classic and recent films, and candid interviews with celebrated Native and non-Native directors, writers, actors, and activists including Clint Eastwood, Robbie Robertson, Graham Greene, Adam Beach, and Zacharias Kunuk, Reel Injun traces the evolution of cinema’s depiction of Native people from the silent film era to present day. October 19 – Becoming Chaz by Fenton Bailey & Randy Barbato http://www.chazbono.net/becomingchaz.html Growing up with famous parents, constantly in the public eye would be hard for anyone. Now imagine that all those images people have seen of you are lies about how you actually felt. Chaz Bono grew up as Sonny and Cher’s adorable golden-haired daughter and felt trapped in a female shell. Becoming Chaz is a bracingly intimate portrait of a person in transition and the relationships that must evolve with him. -

29 WP30 Craig Proofed JR

#30 2018 ISSN 1715-0094 Craig, C. (2018). John Trudell and the Spirit of Life. Workplace, 30, 394-404. CHRISTOPHER CRAIG JOHN TRUDELL AND THE SPIRIT OF LIFE “My ride showed up.” —Posted to John Trudell’s Facebook page just after he passed. The Santee Sioux activist, political philosopher, and poet/musician John Trudell died of cancer on December 8th, 2015. I was sitting in my office when I read the news. His death had been reported erroneously four days before, so it didn’t come as a complete surprise. Nevertheless, I experienced the same kind of sadness I felt when John Lennon died, as though, somehow, I had lost someone close to me even though we had never met. Trudell’s work had inspired me. He fought fearlessly for tribal rights. He also reached across class, gender, and racial lines in order to draw public attention to the oppressive treatment of indigenous people as a symptom of a larger ruling class imperative to colonize the western world. In numerous poems, speeches, and songs, he argues that western society has lost touch with what he calls the “spirit of life.” Industrial capitalism has led to the fall of western society’s natural relationship to the earth. The value of human life no longer resides in the reality that we are made of the earth. Instead it depends on advancing the interests of the very historical forces that had perpetrated our “spiritual genocide.” This learned disrespect for the earth cuts us off from the ancestral knowledge of what it means to be a human being. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

PBS Series Independent Lens Unveils Reel Injun at Summer 2010 Television Critics Association Press Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] Visit the PBS pressroom for more information and/or downloadable images: http://www.pbs.org/pressroom/ PBS Series Independent Lens Unveils Reel Injun at Summer 2010 Television Critics Association Press Tour A Provocative and Entertaining Look at the Portrayal of Native Americans in Cinema to Air November 2010 During Native American Heritage Month (San Francisco, CA)—Cree filmmaker Neil Diamond takes an entertaining, insightful, and often humorous look at the Hollywood Indian, exploring the portrayal of North American Natives through a century of cinema and examining the ways that the myth of “the Injun” has influenced the world’s understanding—and misunderstanding—of Natives. Narrated by Diamond with infectious enthusiasm and good humor, Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian is a loving look at cinema through the eyes of the people who appeared in its very first flickering images and have survived to tell their stories their own way. Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian will air nationally on the upcoming season of the Emmy® Award-winning PBS series Independent Lens in November 2010. Tracing the evolution of cinema’s depiction of Native people from the silent film era to today, Diamond takes the audience on a journey across America to some of cinema’s most iconic landscapes, including Monument Valley, the setting for Hollywood’s greatest Westerns, and the Black Hills of South Dakota, home to Crazy Horse and countless movie legends. -

Neville Brothers -- the first Family of New Orleans Music -- Has Vowed Not to Return to New Orleans

Dec. 15, 2005-- Cyril Neville boarded Amtrak's City of New Orleans train with a full head of steam. He joined singer-songwriter Arlo Guthrie earlier this month for the first leg of a 12-day journey from Chicago to New Orleans, playing concerts along the way to raise funds for victims of Hurricane Katrina. Neville, however, won't be on the train when it rolls into his old hometown. He won't be going home at all. Neville, 56, percussionist-vocalist and youngest member of the Neville Brothers -- the first family of New Orleans music -- has vowed not to return to New Orleans. During a heartfelt conversation before embarking on the train journey, Neville explained he and his wife, Gaynielle, have bought a home in Austin, Texas. Cyril Neville joins his nephew Ivan Neville, as well as the Radiators and the Iguanas as popular New Orleans acts who have settled in Austin. Some even perform in an ad hoc band known as the Texiles. They sing a different song about the promised recovery of New Orleans. "Would I go back to live?" Neville asked. "There's nothing there. And the situation for musicians was a joke. People thought there was a New Orleans music scene -- there wasn't. You worked two times a year: Mardi Gras and Jazz Fest. The only musicians I knew who made a living playing music in New Orleans were Kermit Ruffins and Pete Fountain. Everyone else had to have a day job or go on tour. I have worked more in two months in Austin than I worked in two years in New Orleans. -

KCET/PBS Socal Merger

CONTACT: Ariel Carpenter for KCETLink Media Group [email protected] or 747-201-5243 Jennifer Vides for PBS SoCal [email protected] or 310-237-4516 KCETLINK MEDIA GROUP AND PBS SOCAL ANNOUNCE MERGER New Organization Will Advance PBS Flagship Station in Southern California and Expand Original Content Creation and Innovation for Public Media Locally, and Across the Nation LOS ANGELES, April 25, 2018 – KCETLink Media Group (KCET), a leading national independent broadcast and digital network, and PBS SoCal (KOCE), the flagship PBS organization for Southern California, today announced an agreement to merge the two companies. The merger of equals creates a center for public media innovation and creativity that serves the more than 18 million people living in the Southern California region. The name of the new organization will be announced with the closing of the merger, which is expected to be completed in the first half of 2018. Establishing a powerful PBS flagship organization on the West Coast, the historic union of these two storied institutions creates the opportunity to produce more original programs for multiple channels and platforms that address the diverse community in Southern California and the nation, and innovate new community engagement experiences that educate, inform, entertain, and empower. KCET Board of Directors Chairman Dick Cook will serve as Board Chair, and PBS SoCal President and CEO Andrew Russell will be President and CEO of the new entity, which will be governed by a 32-person Board of Trustees composed of the 14 members from each of the boards of KCETLink and PBS SoCal, as well as four new Board appointees. -

The Seminole Tribune Interviews John Trudell

www.seminoletribe.com Volume XXVII • Number 13 September 21, 2006 What’s New Photo Exhibit ‘A Native View’ Opens Newly Crowned Inside Seminole Tribal Citizens’ Work on Display at Okalee Royalty Debut By Felix DoBosz HOLLYWOOD— On Sept. at Schemitzun 11, the new “A Native View” photo- graphic exhibit opened to the public at By Iretta Tiger the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum at Okalee NORTH STONINGTON, CT — Village. The photographic exhibit fea- For the Seminole Tribe, the Schemitzun tured approximately 60 pieces of Pow wow, the Pequot Tribe’s annual pow assorted black and white and colored wow, has become an important first step Hurricane Preparedness photo images. for the newly crowned Miss Seminole and “We have a brand new exhibit Junior Miss Seminole. Each year this is Meeting opening here today, photographs put where the two ladies make their debut at Page 3 together by myself, Mr. Oliver this nationally known pow wow. Wareham and Ms. Corinne Zepeda, so you’ll see various photographs of peo- ple, places, things, events, we have a little bit of everything,” Brian Zepeda, curator, community outreach coordina- tor and citizen of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, for the Ah-Tha-Thi-Ki Museum, said. “We even have some of the Kissimmee Slough from Big Cypress, we have pictures from Taos, New Mexico, and we also have tribal members that are in the photographs, so we have a little bit for everybody. Friend of Tribe, John “These photos were taken over the process of present day and going Abney, Honored back about five or six years. -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Johnny Burnette TITLE Johnny Burnette And The Rock ’n’ Roll Trio LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BAF 18012 PRICE-CODE BAF EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy180125z FORMAT VINYL album 180g Vinyl • Pressed by Pallas Direct Metal Mastering: H.J. Maucksch at PaulerAcoustics GENRE Rock ‘n’ Roll G One of the first and maybe the greatest rockabilly albums ever! G Includes The Train Kept A'Rollin' – later recorded by the Yardbirds, Aerosmith and many others! G Includes many of the greatest guitar solos from the early days of rock 'n' roll! INFORMATION Johnny Burnette died in 1964 after scoring several pop hits in the early Sixties, including Dreamin', You're Sixteen, and Little Boy Sad. If, in the days or weeks before his death, he had been asked how he would be remembered, he would probably have said for those hits or for the songs he'd written for Ricky Nelson. And he would have been wrong. Today, Johnny Burnette is chiefly remembered for some sessions he cut in 1956 that resulted in no hits, but just about defined rockabilly as an art-form – in fact as a new musical life-form. This album, one of the first-ever rockabilly LPs, is still the best-ever rockabilly LP. From the early 1960s, collectors were paying big money for it. When musicologists and musicians deconstruct rockabilly and when revivalists reconstruct it, they're trying to unravel the magic of Johnny Burnette and the Rock 'n' Roll Trio. -

Billboard-1997-08-30

$6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) $5.95 (U.S.), IN MUSIC NEWS BBXHCCVR *****xX 3 -DIGIT 908 ;90807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 595 001 032898 2 126 1212 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Hall & Oates Return With New Push Records Set PAGE 1 2 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 30, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS 4th -Qtr. Prospects Bright, WMG Assesses Its Future Though Challenges Remain Despite Setbacks, Daly Sees Turnaround BY CRAIG ROSEN be an up year, and I think we are on Retail, Labels Hopeful Indies See Better Sales, the right roll," he says. LOS ANGELES -Warner Music That sense of guarded optimism About New Releases But Returns Still High Group (WMG) co- chairman Bob Daly was reflected at the annual WEA NOT YOUR BY DON JEFFREY BY CHRIS MORRIS looks at 1997 as a transitional year for marketing managers meeting in late and DOUG REECE the company, July. When WEA TYPICAL LOS ANGELES -The consensus which has endured chairman /CEO NEW YORK- Record labels and among independent labels and distribu- a spate of negative m David Mount retailers are looking forward to this tors is that the worst is over as they look press in the last addressed atten- OPEN AND year's all- important fourth quarter forward to a good holiday season. But few years. Despite WARNER MUSI C GROUP INC. dees, the mood with reactions rang- some express con- a disappointing was not one of SHUT CASE. ing from excited to NEWS ANALYSIS cern about contin- second quarter that saw Warner panic or defeat, but clear -eyed vision cautiously opti- ued high returns Music's earnings drop 24% from last mixed with some frustration. -

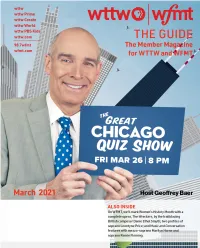

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Mary Lugo 770

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x244 [email protected] Pressroom for more information and/or downloadable images: http://www.itvs.org/pressroom/ Program companion website: http://www.pbs.org/catsofmirikitani Independent Lens: THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI TO HAVE ITS TELEVISION PREMIERE ON PBS, TUESDAY, MAY 8 AT 10:30 PM (Check Local Listings) “THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI is, quite simply, breathtaking — one of the most surprising and unshakable documentaries I can recall.” — New York Sun (San Francisco, CA) — “Make art not war” is Jimmy Mirikitani's motto. The 80-year-old artist was born in Sacramento, California, raised in Hiroshima, Japan, traveled to the U.S. and even cooked for artist Jackson Pollock. But by 2001, Mirikitani was homeless, living on the streets of New York City. As tourists and shoppers hurried past, Mirikitani sat alone on a windy corner in New York’s SoHo, drawing pictures of whimsical cats, bleak internment camps and the angry red flames of the atomic bomb. When local filmmaker Linda Hattendorf stopped to ask about his art, a friendship—detailed in THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI—began that changed both their lives. THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI will have its television premiere on the Emmy® Award-winning PBS series Independent Lens, hosted by Terrence Howard, on Tuesday, May 8 at 10:30 PM (check local listings). In sunshine, rain and snow, Hattendorf returned to document Mirikitani’s drawings, trying to decipher the stories behind them.