May the Circle Remain Unbroken 1 and Other Works with Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict

FRINGE REPORT FRINGE REPORT www.fringereport.com Black Hands / Dead Section Verdict: Springtime for Baader-Meinhof London - MacOwan Theatre - March 05 21-24, 29-31 March 05. 19:30 (22:30) MacOwan Theatre, Logan Place, W8 6QN Box Office 020 8834 0500 LAMDA Baader-Meinhof.com Black Hands / Dead Section is violent political drama about the Baader-Meinhof Gang. It runs for 3 hours in 2 acts with a 15 minute interval. There is a cast of 30 (18M, 12F). The Baader-Meinhof Gang rose during West Germany's years of fashionable middle-class student anarchy (1968-77). Intellectuals supported their politics - the Palestinian cause, anti-US bases in Germany, anti-Vietnam War. Popularity dwindled as they moved to bank robbery, kidnap and extortion. The play covers their rise and fall. It's based on a tight matrix of facts: http://www.fringereport.com/0503blackhandsdeadsection.shtml (1 of 7)11/20/2006 9:31:37 AM FRINGE REPORT Demonstrating student Benno Ohnesorg is shot dead by police (Berlin 2 June, 1967). Andreas Baader and lover Gudrun Ensslin firebomb Frankfurt's Kaufhaus Schneider department store (1968). Ulrike Meinhof springs them from jail (1970). They form the Red Army Faction aka Baader-Meinhof Gang. Key members - Baader, Meinhof, Ensslin, Jan- Carl Raspe, Holger Meins - are jailed (1972). Meins dies by hunger strike (1974). The rest commit suicide: Meinhof (1976), Baader, Ensslin, Raspe (18 October 1977). The play's own history sounds awful. Drama school LAMDA commissioned it as a piece of new writing (two words guaranteed to chill the blood) - for 30 graduating actors. -

Clare Bielby Bewaffnete Kämpferinnen Linksterrorismus, Frauen Und Die Waffe in Der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Von Den Späten 1970Er Jahren Bis Heute

thEma ■ ClarE BiElby Bewaffnete Kämpferinnen Linksterrorismus, Frauen und die Waffe in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland von den späten 1970er Jahren bis heute In Deutschland – wie andernorts – hat die Verbindung von Männlichkeit, Waffe und dem Politischen eine sehr lange Geschichte. Im langen neunzehnten Jahrhundert waren die Waffe 77 und die Gewaltbereitschaft sogar konstitutiv dafür, wie sowohl das Politische als auch die Männlichkeit gedacht wurden,1 und sie spielten eine zentrale diskursive Rolle darin, wie Frauen aus dem politischen Bereich ausgeschlossen wurden.2 Wie Sylvia Schraut dargelegt hat, hatte dieser Ausschluss von Frauen viel mit der Abwehr der Gewaltbereitschaft von Frauen zu tun. Solches Gedankengut scheint bis heute fortzuwirken.3 Es ist daher aufschluss- reich, nach der öffentlichen Wahrnehmung von Frauen zu fragen, die in der Bundesrepublik aus politischen Motiven zur Waffe griffen. In diesem Artikel beschäftige ich mich mit verschiedenen Diskursen über bewaffnete Linksterroristinnen von den 1970ern bis heute. Der Untersuchungszeitraum umfasst damit eine Phase, in der sich Geschlechterrollen radikal wandelten. Zu analysieren ist somit, ob die Veränderung der Geschlechterrollen auch die Vorstellungen und das Reden über bewaffnete Frauen veränderten. Dieser Frage soll exemplarisch anhand vier verschiedener Quellensam- ple nachgegangen werden. Am Beispiel von Presseberichten um 1977, feministischen Reak- tionen darauf in schriftlichen und vor allem filmischen Texten, postterroristischen Autobio- grafien militanter Frauen aus den 1990er Jahren sowie printmedialen und einem filmischen Text aus dem Jahr 2008 untersuche ich, was jeweils sagbar war über Frauen und Waffen und wie sich dies in den letzten gut dreißig Jahren veränderte. Wie werden Waffen auf Weiblich- keit bezogen? Gehen die Autoren und Autorinnen von einem spezifisch weiblichen Waffen- gebrauch aus? Und inwiefern fungiert die bewaffnete Frau als Projektionsfläche? Wir danken dem Spiegel für die Erlaubnis, die Illustration abzudrucken. -

Niemals Wie Die Eltern Tergrundkämpferin Der RAF, Zur Gesuchten Terroristin Wurde

Deutschland Spannend, dramaturgisch dicht, durch- aus selbstkritisch und gut geschrieben er- ZEITGESCHICHTE zählt die heute 51-jährige Margrit Schiller von jenem Jahrzehnt ihrer Jugend, in dem sie von der braven Bürgerstochter zur Un- Niemals wie die Eltern tergrundkämpferin der RAF, zur gesuchten Terroristin wurde. Es ist auch ein typisch Margrit Schiller, in den Siebzigern Mitglied der RAF, hat ihre deutsches Drama von der ewigen Suche nach Wahrheit und Identität, vom schwär- Autobiografie geschrieben. Überraschend merischen Idealismus, der in der Katastro- packend erzählt sie ihre tragische Guerrilla-Geschichte. phe von Lüge und Gewalt endet. Ebenso wie der zeitliche Abstand der rst durch die Begegnung mit An- fern ist. War da was, und was war es ei- Jahre mag die geografische Distanz zum dreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin und gentlich? Ort des Geschehens geholfen haben, sich EUlrike Meinhof wurde der jungen Margrit Schiller, von 1971 bis 1979 Mit- der Vergangenheit zu nähern: 1985 ging sie Frau glasklar: „Ich war mein Leben lang glied der RAF, weiß es genau. Dennoch nach Kuba, heiratete einen Kubaner und belogen worden.“ Margrit Schiller, da- brauchte sie, von alten Freunden und Ge- lebt heute mit ihren beiden Kindern in mals 22 Jahre alt, Psychologiestudentin nossen immer wieder gebremst und ver- Montevideo, der Hauptstadt Uruguays. und aktives Mitglied des „Sozialistischen unsichert, viele Jahre, um ihren „Lebens- Zudem: Margrit Schiller war, obwohl sie Patientenkollektivs“ (SPK), hatte die bericht aus der RAF“ unter dem Titel „Es von Anfang an mit dem Gründungskern der Gründertruppe der „Roten Armee Frak- war ein harter Kampf um meine Erinne- RAF zusammentraf, eine Randfigur. Das tion“ (RAF) mehrere Wochen lang in ih- rung“ tatsächlich zu veröffentlichen**. -

Die RAF – Ein Deutsches Trauma?

ISBN 978-3-89289-044-7 Die RAF – ein deutsches Trauma? Die RAF – ein deutsches Trauma? • „... gegen den Terrorismus steht der Wille des gesamten Volkes.“ (Helmut Schmidt) Caroline Klausing/Verena von Wiczlinski (Hrsg.) Caroline Klausing/Verena Versuch einer historischen Deutung Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Rheinland-Pfalz Am Kronberger Hof 6 • 55116 Mainz Herausgeberinnen: Caroline Klausing und Verena von Wiczlinski Tel.: 0 61 31 - 16 29 70 • Fax: 0 61 31 - 16 29 80 in Zusammenarbeit mit der Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Rheinland-Pfalz E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.politische-bildung-rlp.de Impressum Herausgeberinnen Caroline Klausing und Verena von Wiczlinski in Zusammenarbeit mit der Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Rheinland-Pfalz Am Kronberger Hof 6 55116 Mainz Verantwortlich Bernhard Kukatzki Redaktion Marianne Rohde, Marita Hoffmann Lektorat Marita Hoffmann Umschlaggestaltung Birgit Elm und Llux Agentur & Verlag Abbildungsnachweis Alle Fotografien außer auf Seite 71 und 83: Dr. Andreas Linsenmann Fotografien auf Seite 71 und 83: Jan Hildner Gesamtherstellung Llux Agentur & Verlag e.K. 67065 Ludwigshafen www.buecher.llux.de Mainz 2018 ISBN 978-3-89289-044-7 Die RAF – ein deutsches Trauma? Versuch einer historischen Deutung Inhalt Vorwort 4 Bernhard Kukatzki und Marianne Rohde Zur Einführung 6 Die RAF als gesamtgesellschaftliche Herausforderung – Akteure, Institutionen und Kontroversen Caroline Klausing und Verena von Wiczlinski Der Staat 14 Staat und Terrorismus in der Bundesrepublik -

Zeittafel: Übersicht Der Ereignisse Bis Zum Selbstmord Der RAF- Gefangenen in Stuttgart-Stammheim

Zeittafel: Übersicht der Ereignisse bis zum Selbstmord der RAF- Gefangenen in Stuttgart-Stammheim 2. April 1968 Gudrun Ensslin und Andreas Baader legen Brandbomben in den Frankfurter Kaufhäusern Schneider und Kaufhof, um gewaltsam gegen die Napalmbombardements der USA in Vietnam zu demonstrieren. 3.April 1968 Gudrun Ensslin und Andreas Baader werden verhaftet. 11. April 1968 Ein Rechtsextremist feuert auf dem Kurfürstendamm in Berlin drei Kugeln auf den Studentenführer Rudi Dutschke ab, der das Attentat nur knapp überlebt. Am Abend des Mordanschlags demonstrieren über 1000 Demonstranten vor dem Springer-Verlagshaus in der Kochstraße (heute Rudi-Dutschke-Straße), darunter auch die Journalistin Ulrike Meinhof, die ihr Auto für eine Barrikade zur Verfügung stellt. 31.Oktober 1968 Gudrun Ensslin und Andreas Baader werden zu drei Jahren Haft verurteilt. 13. Juni 1969 Beide werden bis zur Entscheidung über eine Revision des Urteils aus der Haft entlassen. November 1969 Nach der Ablehnung der Revision tauchen Gudrun Ensslin und Andreas Baader in Frankreich, später in Italien unter. Januar 1970 Beide kehren nach Berlin zurück. 4.April 1970 Andreas Baader wird verhaftet. 14. Mai 1970 Bei der Befreiungsaktion von Andreas Baader schließen sich die Journalistin Ulrike Meinhof und der APO-Anwalt Horst Mahler (APO – Außerparlamentarische Opposition) der Gruppe an. Dabei wird ein Justizbeamter lebensgefährlich verletzt. Da die Gruppe danach in den Untergrund geht und in einer Erklärung vom 5. Juni 1970 zur Befreiung Baaders zum Aufbau der RAF aufruft, gilt dieses Datum als Beginn der RAF. Juni bis August 1970 Die Gruppe um Ulrike Meinhof, Andreas Baader und Gudrun Ensslin wird in einem Palästinenserlager militärisch ausgebildet. 29.September 1970 Die Terroristen überfallen zeitgleich drei Banken und erbeuten über 200 000 DM. -

Download (3141Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/57447 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Sisters in Arms? Female Participation in Leftist Political Violence in the Federal Republic of Germany Since 1970 by Katharina Karcher A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of German Studies February 2013 Contents List of Figures 4 Abbreviations 5 Acknowledgements 6 Abstract 7 Declaration 8 Introduction 9 1. Situating the Subject – The Historical, Political, Theoretical and Methodological Background of this Study 22 1.1. Historical and Political Context 22 1.1.1. The Protest and Student Movement in West Germany 22 1.1.2. The New Women’s Movement 34 1.2. The Armed Struggle of the RAF, MJ2, RC and RZ – a Brief Overview 47 1.3. Theoretical Background 59 1.3.1. Terrorism and Political Violence 59 1.3.2. Previous Scholarship on Women’s Involvement in Political Violence 66 1.4. Methodological Framework 76 1.4.1. The Vital Critique of New Feminist Materialisms 76 1.4.2. The Untapped Potential of Theories of Sexual Difference 81 1.4.3. British Cultural Studies – Exploring the Materiality of (Militant) Subcultures 87 1.4.4. -

The Red Army Faction of American-Occupied Germany Is One That Should Be Read by Any Serious Student of Anti- Imperialist Politics

This book about the Red Army Faction of American-occupied Germany is one that should be read by any serious student of anti- imperialist politics. “Volume 1: Projectiles for the People” provides a history of the RAF’s development through the words of its letters and communiqués. What makes the book especially important and relevant, however, is the careful research and documentation done by its editors. From this book you will learn the mistakes of a group that was both large and strong, but which (like our own home-grown attempts in this regard) was unable to successfully communicate with the working class of a “democratic” country on a level that met their needs. While the armed struggle can be the seed of something much larger, it is also another means of reaching out and communicating with the people. Students interested in this historic era would do well to study this book and to internalize both the successes and failures of one of the largest organized armed anti-imperialist organizations operating in Western Europe since World War II. —Ed Mead, former political prisoner, George Jackson Brigade Clear-headed and meticulously researched, this book deftly avoids many of the problems that plagued earlier attempts to tell the brief but enduring history of the RAF. It offers a remarkable wealth of source material in the form of statements and letters from the combatants, yet the authors manage to present it in a way that is both coherent and engaging. Evidence of brutal—and ultimately ineffective—attempts by the state to silence the voices of political prisoners serve as a timely and powerful reminder of the continued need for anti-imperialist prisoners as leaders in our movements today. -

RAF) Und Ihrer Kontexte: Eine Chronik (Überarbeitete Chronik Aus Dem Jahr 2007) Von Jan-Hendrik Schulz

Zur Geschichte der Roten Armee Fraktion (RAF) und ihrer Kontexte: Eine Chronik (Überarbeitete Chronik aus dem Jahr 2007) von Jan-Hendrik Schulz 08.03.1965 Die ersten amerikanischen Bodentruppen landen in Vietnam. Damit verbunden ist die bis 1968 dauernde „Operation Rolling Thunder“, in deren Verlauf die US- amerikanische Luftwaffe den von der „Front National de Libération“ (FNL) – später vereinfacht als „Vietcong“ bezeichnet – organisierten Ho-Chi-Minh-Pfad bombardiert. In der Folgezeit wird die Luftoffensive gegen die Demokratische Republik Vietnam weiter ausgeweitet. Kommentar: Der Vietnam-Konflikt bekam seit Mitte der 1960er-Jahre eine starke Relevanz in der internationalen Studentenbewegung. Besonders prägend für die bundesdeutsche Studentenbewegung war dabei die deutsche Übersetzung von Ernesto Che Guevaras Rede „Schafft zwei, drei, viele Vietnam“. Verantwortlich für die Übersetzung und Veröffentlichung im Jahr 1967 waren Rudi Dutschke und Gaston Salvatore. Ende Oktober 1966 In Frankfurt am Main tagt unter dem Motto „Notstand der Demokratie“ der Kongress gegen die Notstandsgesetze. Eine breite Bewegung von Sozialdemokraten, Gewerkschaftlern und Oppositionellen der Neuen Linken versucht daraufhin mit Sternmärschen, Demonstrationen und anderen Protestformen die geplanten Notstandsgesetze zu verhindern. 01.12.1966 Unter Bundeskanzler Kurt Georg Kiesinger konstituiert sich die Große Koalition. Vizekanzler und Außenminister wird der ehemalige Bürgermeister West-Berlins und Vorsitzende der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands, Willy Brandt. Dezember 1966 Rudi Dutschke ruft auf einer Versammlung des Sozialistischen Deutschen Studentenbundes als Protest gegen die Konstituierung der Großen Koalition zur Gründung einer Außerparlamentarischen Opposition (APO) auf. 19.02.1967 Die „Kommune I“ gründet sich in West-Berlin in der Stierstraße 3. Ihr gehören unter anderem Dieter Kunzelmann, Fritz Teufel, Rainer Langhans und Ulrich Enzensberger an. -

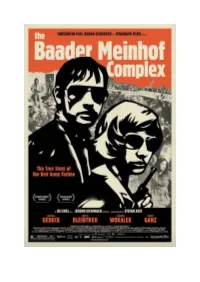

BMC Presskit.Pdf

CONSTANTIN FILM and BERND EICHINGER present A Bernd Eichinger Production An Uli Edel Film Martina Gedeck Moritz Bleibtreu Johanna Wokalek Nadja Uhl Jan Josef Liefers Stipe Erceg Niels Bruno Schmidt Vinzenz Kiefer Simon Licht Alexandra Maria Lara Hannah Herzsprung Tom Schilling Daniel Lommatzsch Sebastian Blomberg Katharina Wackernagel with Heino Ferch and Bruno Ganz Directed by Uli Edel Written and produced by Bernd Eichinger Based on the book by and in consultation with Stefan Aust 0 Release Date: August 21, 2009 New York City www.baadermeinhofmovie.com See website for full release schedule. 2008, 2 hours, 24 minutes, In German with English subtitles. 1 U.S. DISTRIBUTOR Vitagraph Films www.vitagraphfilms.com David Shultz, President [email protected] 310 701 0911 www.vitagraphfilms.com Los Angeles Press Contact: Margot Gerber Vitagraph Films [email protected] New York Press Contact: John Murphy Murphy PR [email protected] 212 414 0408 2 CONTENTS Synopsis Short 04 Press Notice 04 Press Information on the Original Book 04 Facts and Figures on the Film 05 Synopsis Long 06 Chronicle of the RAF 07 Interviews Bernd Eichinger 11 Uli Edel 13 Stefan Aust 15 Martina Gedeck 17 Moritz Bleibtreu 18 Johanna Wokalek 19 Crew / Biography Bernd Eichinger 20 Uli Edel 20 Stefan Aust 21 Rainer Klausmann 21 Bernd Lepel 21 Cast / Biography Martina Gedeck 22 Moritz Bleibtreu 22 Johanna Wokalek 22 Bruno Ganz 23 Nadja Uhl 23 Jan Josef Liefers 24 Stipe Erceg 24 Niels Bruno Schmidt 24 Vinzenz Kiefer 24 Simon Licht 25 Alexandra Maria Lara 25 Hannah Herzsprung 25 Daniel Lommatzsch 25 Sebastian Blomberg 26 Heino Ferch 26 Katharina Wackernagel 26 Anna Thalbach 26 Volker Bruch 27 Hans-Werner Meyer 27 Tom Schilling 27 Thomas Thieme 27 Jasmin Tabatabai 28 Susanne Bormann 28 3 Crew 29 Cast 29 4 SYNOPSIS SHORT Germany in the 1970s: Murderous bomb attacks, the threat of terrorism and the fear of the enemy inside are rocking the very foundations of the still fragile German democracy. -

Terry Delaney Photographs from an Undeclared War Baader-Meinhof: Pictures on the Run 67-77 by Astrid Proll

page 24 • variant • volume 2 number 7 • Spring 1999 Margit Schiller being brought before the Hamburg press, October 1971 Terry Delaney Photographs from an undeclared war Baader-Meinhof: Pictures on the run 67-77 by Astrid Proll From the mid 1970s until the early ‘80s I visited question hanging over the ranks of faces: ‘Have you vanquished enemies on stakes in public places; a kind Germany regularly. Those were different times, it has seen these people?’ There was something chilling of salutary lesson to the potentially disaffected, to be said, and the Europe of ‘no borders’ was still about wanted posters displayed so prominently in a perhaps, or a triumphalist gesture akin to the display some way off. On the train from Brussels to Cologne modern European state although a cursory glance of sporting trophies before one’s loyal support? burly German Border Police stalked the corridors, would not have revealed quite how chilling these The cover of Astrid Proll’s Baader Meinhof, pistols prominent on their robust hips, their posters were. A closer look revealed something odd, Pictures on the Run 67-77 appears to have been taken intimidating manner impressive and accomplished. indeed disturbing, about some of the photographs. from one such poster. There are the rows of young They carried with them what looked for all the world Their subjects were dead. I’m not sure how these faces, serious, but in this case healthy, the pictures like outsized photograph albums. These they would images had been made, whether the corpses had been now somehow reminiscent of one of those American flick through occasionally as they travelled through photographed on mortuary slabs or had somehow High School Yearbooks. -

Remembering the Armed Struggle My Time with the Red Army Faction Margrit Schiller • Foreword: Ann Hansen Afterword: Osvaldo Bayer Appendix: J

Remembering the Armed Struggle My Time with the Red Army Faction Margrit Schiller • Foreword: Ann Hansen Afterword: Osvaldo Bayer Appendix: J. Smith & André Moncourt Margrit Schiller was an early member of the Red Army Faction, the West German urban guerrilla group. In 1971 she was captured and charged with a murder she did not commit, and upon her release she returned to the underground, being captured again in early 1974. She would spend most of the 1970s in prison, enduring isolation conditions meant to break the human spirit, and participating hunger strikes and other acts of resistance along with other political prisoners from the RAF. In Remembering the Armed Struggle, Schiller recounts the process through which she joined her generation’s revolt in the 1960s, going from work with drug users to joining the antipsychiatry political organization the Socialist Patients’ Collective and then the RAF. She tells of how she met and worked alongside the group’s founding members, Ulrike Meinhof, Andreas Baader, Jan-Carl Raspe, Irmgard SUBJECT CATEGORY Möller, and Holger Meins; how she learned the details of the May Offensive and Biography & Autobiography/ other actions while in her prison cell; about the struggles to defend human dignity History: Europe in the most degraded of environments, and the relationships she forged with other women in prison. PRICE Also included are a foreword by Ann Hansen, who situates the draconian prison $19.95 conditions inflicted on the RAF within the context of a global counterinsurgency program that would help spawn the plague of mass incarceration we still face today, ISBN an afterword by the late Osvaldo Bayer, and an appendix by J. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die RAF im Spiegel der Literatur und der westdeutschen Berichterstattung“ Verfasser Michael Siedler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 312 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Geschichte Betreuerin / Betreuer: a.o. Univ. Prof. Dr. Birgit Bolognese-Leuchtenmüller Inhaltsangabe: Terrorismus contra Freiheitskampf:……………………………………………………......1 Die studentische Protestbewegung der 60er Jahre:………………………………………...4 Auf den Weg in den Abgrund, die Tot des Studenten Benno Ohnesorg und das Attentat auf Rudi Dutschke:……………………………………………………………………….....10 Die Studentenbewegung zerfällt und der deutsche Terrorismus nimmt Gestalt an:…...12 Ein kleiner Einblick in die ideologischen Grundlagen der RAF:………………………...14 Herbert Marcuse:……………………………………………………………………………...15 Der erste Impuls zur Entstehung der „Rote Armee Fraktion“:……………………….....17 Die Lebensläufe der Protagonisten:……………………………………………………......22 Zu Gudrun Ensslin:……………………………………………………………………….......23 Zu Andreas Baader:…………………………………………………………………………..25 Zu Ulrike Meinhof:...................................................................................................................27 1 Entstehung der Roten Armee Fraktion durch die Befreiung des „politischen“ Gefangenen Andreas Baader:………………………………………………………………………………32 Die Eskalation beginnt, „Die Offensive 1972“:………………………………………........40 Der Anschlag