Shahabag to Saidpur: Uneasy Intersections and the Politics of Forgetting1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

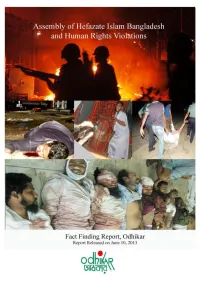

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Mapping the Body-Politic of the Raped Woman and the Nation in Bangladesh

gendered embodiments: mapping the body-politic of the raped woman and the nation in Bangladesh Mookherjee, Nayanika . Feminist Review, suppl. War 88 (Apr 2008): 36-53. Turn on hit highlighting for speaking browsers Turn off hit highlighting Other formats: Citation/Abstract Full text - PDF (206 KB) Abstract (summary) Translate There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation. Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts. This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. I show the ways in which the visual representation of this 'motherland' as fertile countryside, and its idealization primarily through rural landscapes has enabled a crystallization of essentialist gender roles for women. This article is particularly interested in how these images had to be reconciled with the subjectivities of women raped during the Bangladesh Liberation War (Muktijuddho) and the role of the aestheticizing sensibilities of Bangladesh's middle class in that process. [PUBLICATION ABSTRACT] Show less Full Text Translate Turn on search term navigation introduction There has been much academic work outlining the complex links between women and the nation (Yuval-Davis and Anthias, 1989; Yuval-Davis, 1997; Yuval-Davis and Werbner, 1999). Women provide legitimacy to the political projects of the nation in particular social and historical contexts (Kandiyoti, 1991; Chatterjee, 1994). This article focuses on the gendered symbolization of the nation through the rhetoric of the 'motherland' and the manipulation of this rhetoric in the context of national struggle in Bangladesh. -

Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein1 to Taslima Nasrin

ASIATIC, VOLUME 10, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2016 From Islamic Feminism to Radical Feminism: Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein1 to Taslima Nasrin Niaz Zaman2 Independent University, Bangladesh Abstract This paper examines four women writers who have contributed through their writings and actions to the awakening of women in Bangladesh: Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein, Sufia Kamal, Jahanara Imam and Taslima Nasrin. The first three succeeded in making a space for themselves in the Bangladesh tradition and carved a special niche in Bangladesh. All three of them were writers in different genres – poetry, prose, fiction – with the last best known for her diary about 1971. While these iconic figures contributed towards women’s empowerment or people’s rights in general, Taslima Nasrin is the most radically feminist of the group. However, while her voice largely echoes in the voices of young Bangladeshi women today – often unacknowledged – she has been shunned by her own country. The paper attempts to explain why, while other women writers have also said what Taslima Nasrin has, she alone is ostracised. Keywords Islamic feminism, radical feminism, gynocritics, purdah, 1971, Shahbagh protests In this paper, I wish to examine four women writers who have contributed through their writings and actions to the awakening of women in Bangladesh. Beginning with Roquiah Sakhawat Hossein (1880-1932), I will also discuss the roles played by Sufia Kamal (1911-99), Jahanara Imam (1929-94) and Taslima Nasrin (1962-). The first three succeeded in making a space for themselves in the Bangladesh tradition and carved a special niche in Bangladesh. All three of them were writers: Roquiah wrote poems, short stories, a novel, as well as prose pieces; Sufia Kamal was primarily a poet but also wrote a number of short 1 There is some confusion over the spelling of her name. -

Merchant/Company Name

Merchant/Company Name Zone Name Outlet Address A R LADIES FASHION HOUSE Adabor Shamoli Square Shopping Mall Level#3,Shop No#341, ,Dhaka-1207 ADIL GENERAL STORE Adabor HOUSE# 5 ROAD # 4,, SHEKHERTEK, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Archies Adabor Shop no:142,Ground Floor,Japan city Garden,Tokyo square,, Mohammadpur,Dhaka-1207. Archies Gallery Adabor TOKYO SQUARE JAPAN GARDEN CITY, SHOP#155 (GROUND FLOOR) TAJ MAHAL ROAD,RING ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR DHAKA-1207 Asma & Zara Toy Shop Adabor TOKIYO SQUARE, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, LEVEL-1, SHOP-148 BAG GALLARY Adabor SHOP# 427, LEVEL # 4, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING MALL, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, BARCODE Adabor HOUSE- 82, ROAD- 3, MOHAMMADPUR HOUSING SOCIETY, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BARCODE Adabor SHOP-51, 1ST FLOOR, SHIMANTO SHOMVAR, DHANMONDI, DHAKA-1205 BISMILLAH TRADING CORPORATION Adabor SHOP#312-313(2ND FLOOR),SHYAMOLI SQUARE, MIRPUR ROAD,DHAKA-1207. Black & White Adabor 34/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor 32/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor HOUSE-41, ROAD-2, BLOCK-B, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor 15/10, TAJMAHAL ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor EST-02, BAFWAA SHOPPING COMPLEX, BAF SHAHEEN COLLEGE, MOHAKHALI BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-08, URBAN VOID, KA-9/1,. BASHUNDHARA ROAD BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-33, BLOCK-C, LEVEL-08, BASHUNDHARA CITY SHOPPING COMPLEX CASUAL PARK Adabor SHOP NO # 280/281,BLOCK # C LEVEL- 2 SHAYMOLI SQUARE COSMETICS WORLD Adabor TOKYO SQUARE,SHOP#139(G,FLOOR)JAPAN GARDEN CITY,24/A,TAJMOHOL ROAD(RING ROAD), BLOCK#C, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 DAZZLE Adabor SHOP#532, LEVEL-5, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING COMPLEX, JAPAN GARDEN CITY (RING ROAD) MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207. -

2 Crowd Violence in East Pakistan/ Bangladesh 1971–1972

Christian Gerlach 2 Crowd Violence in East Pakistan/ Bangladesh 1971–1972 Introduction Some recent scholarship links violent persecutions in the 20th century to the rise of mass political participation.1 This paper substantiates this claim by exploring part of a country’s history of crowd violence. Such acts constitute a specific form of participation in collective violence and shaping it. There are others such as forming local militias, small informal violent gangs or a guerrilla, calls for vio- lence in petitions or non-violent demonstrations and also acting through a state apparatus, meaning that functionaries contribute personal ideas and perceptions to the action of a bureaucracy in some persecution. Therefore it seems to make sense to investigate specific qualities of participation in crowd violence. Subject to this inquiry is violence against humans by large groups of civilians, with no regard to other collectives of military or paramilitary groups, as large as they may have been. My approach to this topic is informed by my interest in what I call “ex- tremely violent societies.” This means social formations in which, for some pe- riod, various population groups become victims of mass violence in which, alongside state organs, many members of several social groups participate for a variety of reasons.2 Aside from the participatory character of violence, this is also about its multiple target groups and sometimes its multipolar character. Applied here, this means to compare the different degrees to which crowd vio- lence was used by and against different groups and why. It is evident that the line between perpetrators and bystanders is especially blurred within violent crowds. -

Curriculum Vitae June 2015

Curriculum Vitae June 2015 Dr. Maidul Islam BA (Calcutta), MA (JNU), MPhil (JNU), DPhil (Oxon) Institutional Address: Presidency University, 86/1, College Street, Kolkata-700073, India. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Permanent Address: 28/6, Tollygunge Circular Road, P.O.-New Alipore, Kolkata-700053. Current Position: Assistant Professor in Political Science, Presidency University, Kolkata. Date of Birth: 5th February, 1980; Calcutta Citizenship: Indian University Education 2007-2012: DPhil in Politics, Brasenose College and Department of Politics & International Relations, University of Oxford. Dissertation: Limits of Islamism: Ideological Articulations of Jamaat-e-Islami in Contemporary India and Bangladesh. Supervisor: Dr. Nandini Gooptu. (Result: Pass and Awarded) 2005-2007: MPhil in Political Science, Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Dissertation: Understanding Political Islam in India: Ideology and Organisation of Jamaat-e-Islami Hind. Supervisor: Prof. Zoya Hasan. (Result: First Class; FGPA: 7.69/9 [85.44%]) 2003-2005: MA in Political Science, Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. (Result: First Class; FGPA: 6.81/9 [75.66%]) 2000-2003: BA (Honours) in Political Science, Presidency College, University of Calcutta; Subsidiary Subjects: Economics & History. Compulsory Subjects: English, Bengali and Environmental Studies. (Result: Upper Second Class; 55.62%) Areas of Research Interest: Political Theory, Political Philosophy, Identity Politics, Contemporary South Asian Politics, Indian Muslims and Cinema. Past Employment Fellow, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla [28th February, 2013—23rd December, 2013] Assistant Professor, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Tuljapur campus) [6th August, 2012— 26th February, 2013]. -

An Analysis of Online Discursive Battle of Shahbag Protest 2013 in Bangladesh

SEXISM IN ‘ONLINE WAR’: AN ANALYSIS OF ONLINE DISCURSIVE BATTLE OF SHAHBAG PROTEST 2013 IN BANGLADESH By Nasrin Khandoker Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies. Supervisor: Professor Elissa Helms Budapest, Hungary 2014 CEU eTD Collection I Abstract This research is about the discursive battle between radical Bengali nationalists and the Islamist supporters of accused and convicted war criminals in Bangladesh where the gendered issues are used as weapons. In Bangladesh, the online discursive frontier emerged from 2005 as a continuing battle extending from the 1971 Liberation War when the punishment of war criminals and war rapists became one of the central issues of political and public discourse. This online community emerged with debate about identity contest between the Bengali nationalist ‘pro-Liberation War’ and the ‘Islamist’ supporters of the accused war criminals. These online discourses created the background of Shahbag protest 2013 demanding the capital punishment of one convicted criminal and at the time of the protest, the online community played a significant role in that protest. In this research as a past participant of Shahbag protest, I examined this online discourse and there gendered and masculine expression. To do that I problematized the idea of Bengali and/or Muslim women which is related to the identity contest. I examined that, to protest the misogynist propaganda of Islamist fundamentalists in Bangladesh, feminists and women’s organizations are aligning themselves with Bengali nationalism and thus cannot be critical about the gendered notions of nationalism. I therefore, tried to make a feminist scholarly attempt to be critical of the misogynist and gendered notion of both the Islamists and Bengali nationalists to contribute not only a critical examination of masculine nationalist rhetoric, but will also to problematize that developmentalist feminist approach. -

Students, Space, and the State in East Pakistan/Bangladesh 1952-1990

1 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 A dissertation presented by Samantha M. R. Christiansen to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts September, 2012 2 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 by Samantha M. R. Christiansen ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate School of Northeastern University September, 2012 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the history of East Pakistan/Bangladesh’s student movements in the postcolonial period. The principal argument is that the major student mobilizations of Dhaka University are evidence of an active student engagement with shared symbols and rituals across time and that the campus space itself has served as the linchpin of this movement culture. The category of “student” developed into a distinct political class that was deeply tied to a concept of local place in the campus; however, the idea of “student” as a collective identity also provided a means of ideological engagement with a globally imagined community of “students.” Thus, this manuscript examines the case study of student mobilizations at Dhaka University in various geographic scales, demonstrating the levels of local, national and global as complementary and interdependent components of social movement culture. The project contributes to understandings of Pakistan and Bangladesh’s political and social history in the united and divided period, as well as provides a platform for analyzing the historical relationship between social movements and geography that is informative to a wide range of disciplines. -

The Food Riots That Never Were: the Moral and Political Economy of Food Security in Bangladesh Naomi Hossain Ferdous Jahan

The Food Riots That Never Were: The moral and political economy of food security in Bangladesh Naomi Hossain Ferdous Jahan 1 This is an Open Access report distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode To Cite This Report: Hossain, N. and F. Jahan (2014) ‘The food riots that never were: the moral and political economy of food security in Bangladesh’. Food Riots and Food Rights project report. Brighton/ Dhaka: Institute of Development Studies/University of Dhaka. www.foodriots.org This research has been generously funded by the UK Department for International Development- Economic and Social Research Council (DFID-ESRC) Joint Programme on Poverty Alleviation (Grant reference ES/J018317/1). Caption: Protesting garment workers clash with police in Dhaka (Photo: Andrew Biraj) Design & Layout: Job Mwanga i THE FOOD RIOTS THAT NEVER WERE: THE MORAL AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF FOOD SECURITY IN BANGLADESH ABOUT THIS WORKING PAPER SERIES The green revolution and the global integration of food markets were supposed to relegate scarcity to the annals of history. So why did thousands of people in dozens of countries take to the streets when world food prices spiked in 2008 and 2011? Are food riots the surest route to securing the right to food in the twenty-first century? We know that historically, food riots marked moments of crisis in the adjustment to more market-oriented or capitalist food and economic systems. -

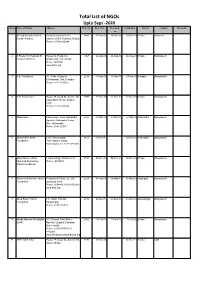

Upto Sept -2020 Sl.No Name of Ngos Address Reg

Total List of NGOs Upto Sept -2020 Sl.no Name of NGOs Address Reg. No. Reg. Date Renewed Valid upto District Country Remarks on 1 3F-United Federation of Road-54, Houase-11/A, 2843 10-Dec-13 10-Dec-18 10-Dec-28 Dhaka Denmark Danish Workers Apartment-B/4, Gulshan, Dhaka, Phone: 01764-405244 2 A Shelter for Helpless Ill House-52, Road-3/A, 1067 26-Aug-96 26-Aug-16 26-Aug-21 Dhaka Bangladesh Children (ASHIC) Dhanmondi, R/A, Dhaka Phone :9673982 www.ashic.org 3 A.B. Foundation Vill., Post + Upazilla: 2024 05-Apr-05 05-Apr-15 05-Apr-20 Dinajpur Bangladesh Chirirbandar, Dist: Dinajpur Phone: 01711-530611 4 A.M. Foster Care House-38, Road-04, Sector--05, 2397 22-Dec-08 22-Dec-13 22-Dec-18 Dhaka Bangladesh Uttara Model Town, Dhaka- 1230. Phone: 01715-475282 5 Abalamban Pachimpara, Post: Gaibandha, 2326 27-Mar-08 27-Mar-18 27-Mar-28 Gaibandha Bangladesh Upazilla: Gaibandha Sadar, Dist.: Gaibandha. Phone: 0541-62388 6 Abdul Halim Khan 1257, Khorompatty, 3123 19-Dec-17 19-Dec-27 Kishorganj Bangladesh Foundation Post+Upazila: Sadar, Kishoreganj, Tel: 01711681660 7 Abdul Momen Khan 5 Momenbagh, Dhaka-1217 0780 04-Dec-93 04-Dec-18 04-Dec-28 Dhaka Bangladesh Memorial Foundation Phone : 9330323 (Khan Foundation) 8 Abdur Rashid Khan Thakur Chapailghat Road, UZ+Zila: 2229 05-Aug-07 08-May-17 08-May-27 Gopalganj Bangladesh Foundation gopalganj-8100 Phone: 8034489, 01911-352919 www.arktf.org 9 Abed Satter Pathen 118 Isdair, Fatullah, 2842 03-Dec-13 03-Dec-18 03-Dec-28 Narayanganj Bangladesh Foundation Narayanganj Phone: 0190-251515 10 Abeda Mannan Foundation Vill: Chulash, Post Office: 2582 15-Jun-10 15-Jun-15 15-Jun-20 Dhaka Bangladesh (AMF) Maricha, Upazilla: Debidwar, Dist: Comilla. -

Tormenting 71 File-01

TORMENTING SEVENTY ONE An account of Pakistan army’s atrocities during Bangladesh liberation war of 1971 Interviewed and reported by Ruhul Motin, Dr. Sukumar Biswas Julfikar Ali Manik, Mostafa Hossain Krishna Bhowmik, Gourango Nandi Abdul Kalam Azad, Prithwijeet Sen Rishi Translated by Zahid Newaz, Ziahul Haq Swapan Nazrul Islam Mithu, Nadeem Qadir Edited by Shahriar Kabir Nirmul Committee (Committee for Resisting Killers & Collaborators of Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971) Ó Nirmul Committee First Edition Dhaka, November, 1999 Published by Kazi Mukul General Secretary, Nirmul Committee Ga-16, Mohakhali, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh. Phone : 8822985, 8828703 E-mail : [email protected] Printed by Dana Printers Limited Ga-16 Mohakhali Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh Cover designed by Amal Das, based on noted painter Kamrul Hassan’s oil painting tilled ‘Bangladesh 1971’ Photographs : Courtesy : Muktijuddher Aalokchitro, an albam published by Liberation War History Project of Bangladesh Government, Bangla Name Desh by Ananda Publishers, Calcutta and Album of Kishore Parekh, India Price : Tk. 250 (US $ 20.00 in abroad) Dedicated to Those who are campaigning for the trial of 1971 war criminals in Bangladesh and those who supporting this cause from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and several other countries across the world Contents Introduction I was put in a gunny bag and kept in the scorching sun Brigadier (Retd.) M. R. Majumdar One day they forced me to lie on a slab of ice Lt. Col. Masoudul Hossain Khan (Retd.) They pressed burning cigarettes -

The Paradoxes of Bangladesh's Shahbag Protests

The paradoxes of Bangladesh’s Shahbag protests blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2013/03/21/the-paradoxes-of-bangladeshs-shahbag-protests/ 2013-3-21 LSE’s David Lewis contextualises recent protests in Dhaka and explains why subsequent political violence could threaten Bangladesh’s democratic institutions. It began last month as a peaceful protest reminiscent of the ‘Arab spring’ as hundreds of thousands of youngsters, mobilised by Facebook messages and other online networking, gathered at the Shahbag intersection in Dhaka to seek justice for war crimes committed by members of Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh (JIB), Bangladesh’s largest Islamic party. But the Dhaka protests have been followed by an outbreak of political and militant violence that now threatens Bangladesh’s democratic institutions. India has supported the Shahbag protests, with National Security Adviser Shivshankar Menon praising the efforts of Bangladeshi youth to uphold democracy and challenge extremism. But the violence signals a crucial moment for domestic politics in Bangladesh, particularly as the clashes raise questions about the country’s identity: secular or Islamic? The emergence of the Shahbag protest has already been hailed as a key moment, representing a new grassroots movement expressing its distaste for the country’s corrupt political culture. The protests reflected a desire to heal the country’s wounds by seeking justice once and for all for the events of 1971, when the country secured independence from Pakistan following a violent war of secession. There was a strong element of youth participation in the protests as well as significant female presence; demands for justice and national reconciliation were coupled with anger at the current government.