ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 7(7), 420-429

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

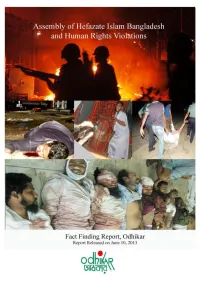

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Phd Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

Khan, Adeeba Aziz (2015) Electoral institutions in Bangladesh : a study of conflicts between the formal and the informal. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/23587 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. Electoral Institutions in Bangladesh: A Study of Conflicts Between the Formal and the Informal Adeeba Aziz Khan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Law 2015 Department of Law SOAS, University of London I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information

BANGLADESH COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Bangladesh April 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.7 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.3 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 - 4.45 Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 4.1 - 4.4 1972 –1982 4.5 - 4.8 1983 – 1990 4.9 - 4.14 1991 – 1999 4.15 - 4.26 2000 – the present 4.27 - 4.45 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.51 The constitution 5.1 - 5.3 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.4 - 5.6 Political System 5.7 - 5.13 Judiciary 5.14 - 5.21 Legal Rights /Detention 5.22 - 5.30 - Death Penalty 5.31 – 5.32 Internal Security 5.33 - 5.34 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.35 – 5.37 Military Service 5.38 Medical Services 5.39 - 5.45 Educational System 5.46 – 5.51 6. Human Rights 6.1- 6.107 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.53 Overview 6.1 - 6.5 Torture 6.6 - 6.7 Politically-motivated Detentions 6.8 - 6.9 Police and Army Accountability 6.10 - 6.13 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.14 – 6.23 Freedom of Religion 6.24 - 6.29 Hindus 6.30 – 6.35 Ahmadis 6.36 – 6.39 Christians 6.40 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.41 Employment Rights 6.42 - 6.47 People Trafficking 6.48 - 6.50 Freedom of Movement 6.51 - 6.52 Authentication of Documents 6.53 6.B Human Rights – Specific Groups 6.54 – 6.85 Ethnic Groups Biharis 6.54 - 6.60 The Tribals of the Chittagong Hill Tracts 6.61 - 6.64 Rohingyas 6.65 – 6.66 Women 6.67 - 6.71 Rape 6.72 - 6.73 Acid Attacks 6.74 Children 6.75 - 6.80 - Child Care Arrangements 6.81 – 6.84 Homosexuals 6.85 Bangladesh April 2004 6.C Human Rights – Other Issues 6.86 – 6.89 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 6.86 - 6.89 Annex A: Chronology of Events Annex B: Political Organisations Annex C: Prominent People Annex D: References to Source Material Bangladesh April 2004 1. -

Merchant/Company Name

Merchant/Company Name Zone Name Outlet Address A R LADIES FASHION HOUSE Adabor Shamoli Square Shopping Mall Level#3,Shop No#341, ,Dhaka-1207 ADIL GENERAL STORE Adabor HOUSE# 5 ROAD # 4,, SHEKHERTEK, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Archies Adabor Shop no:142,Ground Floor,Japan city Garden,Tokyo square,, Mohammadpur,Dhaka-1207. Archies Gallery Adabor TOKYO SQUARE JAPAN GARDEN CITY, SHOP#155 (GROUND FLOOR) TAJ MAHAL ROAD,RING ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR DHAKA-1207 Asma & Zara Toy Shop Adabor TOKIYO SQUARE, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, LEVEL-1, SHOP-148 BAG GALLARY Adabor SHOP# 427, LEVEL # 4, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING MALL, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, BARCODE Adabor HOUSE- 82, ROAD- 3, MOHAMMADPUR HOUSING SOCIETY, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BARCODE Adabor SHOP-51, 1ST FLOOR, SHIMANTO SHOMVAR, DHANMONDI, DHAKA-1205 BISMILLAH TRADING CORPORATION Adabor SHOP#312-313(2ND FLOOR),SHYAMOLI SQUARE, MIRPUR ROAD,DHAKA-1207. Black & White Adabor 34/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor 32/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor HOUSE-41, ROAD-2, BLOCK-B, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor 15/10, TAJMAHAL ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor EST-02, BAFWAA SHOPPING COMPLEX, BAF SHAHEEN COLLEGE, MOHAKHALI BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-08, URBAN VOID, KA-9/1,. BASHUNDHARA ROAD BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-33, BLOCK-C, LEVEL-08, BASHUNDHARA CITY SHOPPING COMPLEX CASUAL PARK Adabor SHOP NO # 280/281,BLOCK # C LEVEL- 2 SHAYMOLI SQUARE COSMETICS WORLD Adabor TOKYO SQUARE,SHOP#139(G,FLOOR)JAPAN GARDEN CITY,24/A,TAJMOHOL ROAD(RING ROAD), BLOCK#C, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 DAZZLE Adabor SHOP#532, LEVEL-5, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING COMPLEX, JAPAN GARDEN CITY (RING ROAD) MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207. -

1 Introduction

210 Notes Notes 1Introduction 1 See Taj I. Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, in H. Mutalib and T.I. Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslims and the Modern State, pp. 100–34. 2The Government of Bangladesh, The Constitution of the People’s Repub- lic of Bangladesh, Section 28 (1 & 2), Government Printing Press, Dhaka, 1990, p. 19. 3See Coordinating Council for Human Rights in Bangladesh, (CCHRB) Bangladesh: State of Human Rights, 1992, CCHRB, Dhaka; Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence Against Women, Institute of Democratic Rights, Dhaka, 1991; US Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Prac- tices for 1992, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1993; Rushdie Begum et al., Nari Nirjatan: Sangya O Bishleshon (Bengali), Narigrantha Prabartana, Dhaka, 1992, passim. 4 CCHRB Report, 1993, p. 69. 5 Immigration and Refugee Board (Canada), Report, ‘Women in Bangla- desh’, Human Rights Briefs, Ottawa, 1993, pp. 8–9. 6Ibid, pp. 9–10. 7 The Daily Star, 18 January 1998. 8Rabia Bhuiyan, Aspects of Violence, pp. 14–15. 9 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 20. 10 Taj Hashmi, ‘Islam in Bangladesh Politics’, p. 117. 11 Immigration and Refugee Board Report, ‘Women in Bangladesh’, p. 6. 12 Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid, ‘Women, Islam, and the State: Subordination and Resistance’, paper presented at the Bengal Studies Conference (28–30 April 1995), Chicago, pp. 1–2. 13 Ibid, pp. 4–5. 14 U.A.B. Razia Akter Banu, ‘Jamaat-i-Islami in Bangladesh: Challenges and Prospects’, in Hussin Mutalib and Taj Hashmi (eds), Islam, Muslim and the Modern State, pp. 86–93. 15 Lynne Brydon and Sylvia Chant, Women in the Third World: Gender Issues in Rural and Urban Areas, p. -

Curriculum Vitae June 2015

Curriculum Vitae June 2015 Dr. Maidul Islam BA (Calcutta), MA (JNU), MPhil (JNU), DPhil (Oxon) Institutional Address: Presidency University, 86/1, College Street, Kolkata-700073, India. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Permanent Address: 28/6, Tollygunge Circular Road, P.O.-New Alipore, Kolkata-700053. Current Position: Assistant Professor in Political Science, Presidency University, Kolkata. Date of Birth: 5th February, 1980; Calcutta Citizenship: Indian University Education 2007-2012: DPhil in Politics, Brasenose College and Department of Politics & International Relations, University of Oxford. Dissertation: Limits of Islamism: Ideological Articulations of Jamaat-e-Islami in Contemporary India and Bangladesh. Supervisor: Dr. Nandini Gooptu. (Result: Pass and Awarded) 2005-2007: MPhil in Political Science, Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Dissertation: Understanding Political Islam in India: Ideology and Organisation of Jamaat-e-Islami Hind. Supervisor: Prof. Zoya Hasan. (Result: First Class; FGPA: 7.69/9 [85.44%]) 2003-2005: MA in Political Science, Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. (Result: First Class; FGPA: 6.81/9 [75.66%]) 2000-2003: BA (Honours) in Political Science, Presidency College, University of Calcutta; Subsidiary Subjects: Economics & History. Compulsory Subjects: English, Bengali and Environmental Studies. (Result: Upper Second Class; 55.62%) Areas of Research Interest: Political Theory, Political Philosophy, Identity Politics, Contemporary South Asian Politics, Indian Muslims and Cinema. Past Employment Fellow, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla [28th February, 2013—23rd December, 2013] Assistant Professor, Tata Institute of Social Sciences (Tuljapur campus) [6th August, 2012— 26th February, 2013]. -

An Analysis of Online Discursive Battle of Shahbag Protest 2013 in Bangladesh

SEXISM IN ‘ONLINE WAR’: AN ANALYSIS OF ONLINE DISCURSIVE BATTLE OF SHAHBAG PROTEST 2013 IN BANGLADESH By Nasrin Khandoker Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies. Supervisor: Professor Elissa Helms Budapest, Hungary 2014 CEU eTD Collection I Abstract This research is about the discursive battle between radical Bengali nationalists and the Islamist supporters of accused and convicted war criminals in Bangladesh where the gendered issues are used as weapons. In Bangladesh, the online discursive frontier emerged from 2005 as a continuing battle extending from the 1971 Liberation War when the punishment of war criminals and war rapists became one of the central issues of political and public discourse. This online community emerged with debate about identity contest between the Bengali nationalist ‘pro-Liberation War’ and the ‘Islamist’ supporters of the accused war criminals. These online discourses created the background of Shahbag protest 2013 demanding the capital punishment of one convicted criminal and at the time of the protest, the online community played a significant role in that protest. In this research as a past participant of Shahbag protest, I examined this online discourse and there gendered and masculine expression. To do that I problematized the idea of Bengali and/or Muslim women which is related to the identity contest. I examined that, to protest the misogynist propaganda of Islamist fundamentalists in Bangladesh, feminists and women’s organizations are aligning themselves with Bengali nationalism and thus cannot be critical about the gendered notions of nationalism. I therefore, tried to make a feminist scholarly attempt to be critical of the misogynist and gendered notion of both the Islamists and Bengali nationalists to contribute not only a critical examination of masculine nationalist rhetoric, but will also to problematize that developmentalist feminist approach. -

The Food Riots That Never Were: the Moral and Political Economy of Food Security in Bangladesh Naomi Hossain Ferdous Jahan

The Food Riots That Never Were: The moral and political economy of food security in Bangladesh Naomi Hossain Ferdous Jahan 1 This is an Open Access report distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode To Cite This Report: Hossain, N. and F. Jahan (2014) ‘The food riots that never were: the moral and political economy of food security in Bangladesh’. Food Riots and Food Rights project report. Brighton/ Dhaka: Institute of Development Studies/University of Dhaka. www.foodriots.org This research has been generously funded by the UK Department for International Development- Economic and Social Research Council (DFID-ESRC) Joint Programme on Poverty Alleviation (Grant reference ES/J018317/1). Caption: Protesting garment workers clash with police in Dhaka (Photo: Andrew Biraj) Design & Layout: Job Mwanga i THE FOOD RIOTS THAT NEVER WERE: THE MORAL AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF FOOD SECURITY IN BANGLADESH ABOUT THIS WORKING PAPER SERIES The green revolution and the global integration of food markets were supposed to relegate scarcity to the annals of history. So why did thousands of people in dozens of countries take to the streets when world food prices spiked in 2008 and 2011? Are food riots the surest route to securing the right to food in the twenty-first century? We know that historically, food riots marked moments of crisis in the adjustment to more market-oriented or capitalist food and economic systems. -

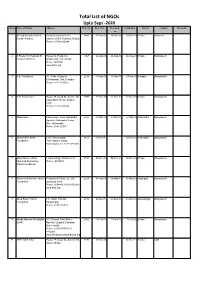

Upto Sept -2020 Sl.No Name of Ngos Address Reg

Total List of NGOs Upto Sept -2020 Sl.no Name of NGOs Address Reg. No. Reg. Date Renewed Valid upto District Country Remarks on 1 3F-United Federation of Road-54, Houase-11/A, 2843 10-Dec-13 10-Dec-18 10-Dec-28 Dhaka Denmark Danish Workers Apartment-B/4, Gulshan, Dhaka, Phone: 01764-405244 2 A Shelter for Helpless Ill House-52, Road-3/A, 1067 26-Aug-96 26-Aug-16 26-Aug-21 Dhaka Bangladesh Children (ASHIC) Dhanmondi, R/A, Dhaka Phone :9673982 www.ashic.org 3 A.B. Foundation Vill., Post + Upazilla: 2024 05-Apr-05 05-Apr-15 05-Apr-20 Dinajpur Bangladesh Chirirbandar, Dist: Dinajpur Phone: 01711-530611 4 A.M. Foster Care House-38, Road-04, Sector--05, 2397 22-Dec-08 22-Dec-13 22-Dec-18 Dhaka Bangladesh Uttara Model Town, Dhaka- 1230. Phone: 01715-475282 5 Abalamban Pachimpara, Post: Gaibandha, 2326 27-Mar-08 27-Mar-18 27-Mar-28 Gaibandha Bangladesh Upazilla: Gaibandha Sadar, Dist.: Gaibandha. Phone: 0541-62388 6 Abdul Halim Khan 1257, Khorompatty, 3123 19-Dec-17 19-Dec-27 Kishorganj Bangladesh Foundation Post+Upazila: Sadar, Kishoreganj, Tel: 01711681660 7 Abdul Momen Khan 5 Momenbagh, Dhaka-1217 0780 04-Dec-93 04-Dec-18 04-Dec-28 Dhaka Bangladesh Memorial Foundation Phone : 9330323 (Khan Foundation) 8 Abdur Rashid Khan Thakur Chapailghat Road, UZ+Zila: 2229 05-Aug-07 08-May-17 08-May-27 Gopalganj Bangladesh Foundation gopalganj-8100 Phone: 8034489, 01911-352919 www.arktf.org 9 Abed Satter Pathen 118 Isdair, Fatullah, 2842 03-Dec-13 03-Dec-18 03-Dec-28 Narayanganj Bangladesh Foundation Narayanganj Phone: 0190-251515 10 Abeda Mannan Foundation Vill: Chulash, Post Office: 2582 15-Jun-10 15-Jun-15 15-Jun-20 Dhaka Bangladesh (AMF) Maricha, Upazilla: Debidwar, Dist: Comilla. -

The Paradoxes of Bangladesh's Shahbag Protests

The paradoxes of Bangladesh’s Shahbag protests blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2013/03/21/the-paradoxes-of-bangladeshs-shahbag-protests/ 2013-3-21 LSE’s David Lewis contextualises recent protests in Dhaka and explains why subsequent political violence could threaten Bangladesh’s democratic institutions. It began last month as a peaceful protest reminiscent of the ‘Arab spring’ as hundreds of thousands of youngsters, mobilised by Facebook messages and other online networking, gathered at the Shahbag intersection in Dhaka to seek justice for war crimes committed by members of Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh (JIB), Bangladesh’s largest Islamic party. But the Dhaka protests have been followed by an outbreak of political and militant violence that now threatens Bangladesh’s democratic institutions. India has supported the Shahbag protests, with National Security Adviser Shivshankar Menon praising the efforts of Bangladeshi youth to uphold democracy and challenge extremism. But the violence signals a crucial moment for domestic politics in Bangladesh, particularly as the clashes raise questions about the country’s identity: secular or Islamic? The emergence of the Shahbag protest has already been hailed as a key moment, representing a new grassroots movement expressing its distaste for the country’s corrupt political culture. The protests reflected a desire to heal the country’s wounds by seeking justice once and for all for the events of 1971, when the country secured independence from Pakistan following a violent war of secession. There was a strong element of youth participation in the protests as well as significant female presence; demands for justice and national reconciliation were coupled with anger at the current government. -

List of Trainees of Egp Training

Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Summary of Participants # Type of Training No. of Participants 1 Procuring Entity (PE) 876 2 Registered Tenderer (RT) 1593 3 Organization Admin (OA) 59 4 Registered Bank User (RB) 29 Total 2557 Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Number of Procuring Entity (PE) Participants: 876 # Name Designation Organization Organization Address 1 Auliullah Sub-Technical Officer National University, Board Board Bazar, Gazipur 2 Md. Mominul Islam Director (ICT) National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 3 Md. Mizanoor Rahman Executive Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 4 Md. Zillur Rahman Assistant Maintenance Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 5 Md Rafiqul Islam Sub Assistant Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 6 Mohammad Noor Hossain System Analyst National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 7 Md. Anisur Rahman Programmer Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-999 8 Sanjib Kumar Debnath Deputy Director Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-1000 9 Mohammad Rashedul Alam Joint Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 10 Md. Enamul Haque Assistant Director(Construction) Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 11 Nazneen Khanam Deputy Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 12 Md. -

Unclaimed Deposit Statement for Bank's Website-As on 31.12.2020

SL Name of Branch Present Address Permanent Address Account Type Name of Account/ Beneficiary Account/Instrument No. Father's Name Amount BB Cheque Amount Date of Transfer Remarks No. 1 SKB Branch Law Chamber, Amin Court, 5th Floor, 62-63 Motijheel C/A, Dhaka. NA Current Account Graham John Walker 0003-0210001547 NA 130,569.00 130,569.00 18-Aug-14 2 SKB Branch NA NA NA Grafic System Pvt. Ltd. PAA00014522 NA 775.00 3 SKB Branch NA NA NA Elesta Security Services Ltd. PAA00015444 NA 4,807.00 5,582.00 22-Nov-15 4 SKB Branch 369,New North Goran Khilgaon,Dhaka. Vill-Maziara, PO-Jibongonj Bazar, Nabinagar, Brahman Baria Savings Account Farida Iqbal 0003-0310010964 Khondokar Iqbal Hossain 1,212.00 5 SKB Branch Dosalaha Villa, Sec#6,Block#D,Road#9, House# 11,Mirpur ,Dhaka. Vill-Balurchar, PO-Baksha Nagar,PS-Nababgonj,Dist-Dhaka. Savings Account Md. Shah Alam 0003-0310009190 Late Abdur Razzak 975.00 6 SKB Branch H#26(2nd floor)Road# 111,Block-F,Banani,Dhaka. Vill- Chota Khatmari,PO-Joymonirhat, PS-Bhurungamari,Dist-Kurigram. Savings Account S.M. Babul Akhter 0003-0310014077 Md. Amjad Hossain 782.00 7 SKB Branch 135/1,1st Floor Malibag,Dhaka. Vill-Bhairabdi,PO-Sultanshady,PS-Araihazar,Dist-Narayangonj. Savings Account Mohammad Mogibur Rahman 0003-0310012622 Md. Abdur Rashid 416.00 14,951.00 6-Jun-16 8 SKB Branch A-1/16,Sonali Bank Colony, Motijheel,Dhaka. 12/2,Nabin Chanra Goshwari Road, Shampur, Dhaka. Savings Account Salina Akter Banu 0003-0310012668 Md. Rahmat Ali 966.00 9 SKB Branch Cosmos Center 69/1,New Circular Road,Malibage,Dhaka.