Koch Dynasty: a Political Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

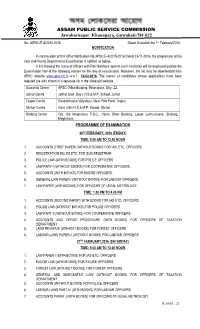

Notification: Half Yearly Departmental Examination-2015

ASSAM PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Jawaharnagar, Khanapara, Guwahati-781 022 No. 30PSC/E-4/2015-2016 Dated Guwahati the 1st February/2016 NOTIFICATION In continuation of this office Notification No.3PSC/E-4/2015-2016 Dated 23-11-2016, the programme of the next Half-Yearly Departmental Examination is notified as below. A list showing the name of officers with Roll Numbers against each candidate will be displayed outside the Examination Hall at the following centres on the day of examination. Moreover, the list may be downloaded from APSC website www.apsc.nic.in w.e.f. 10-02-2016. The names of candidates whose applications have been rejected are also shown in a separate list in the aforesaid website. Guwahati Centre APSC Office Building , Khanapara, Ghy. -22. Jorhat Centre Jorhat Govt. Boy’s H.S & M.P. School, Jorhat Tezpur Centre Rastrab has ha Vidyalaya , Near Polo Field, Tezpur Silchar Centre Govt. Girls H.S & M.P. School, Silchar Shillong Cen tre O/o. the Meghalaya P.S.C., Horse Shoe Building, Lower Lachumiaere, Shillong, Meghalaya. PROGRAMME OF EXAMINATION 26 TH FEBRUARY, 2016 (FRIDAY) TIME: 9.00 AM TO 12.00 NOON 1. ACCOUNTS (FIRST PAPER) WITHOUT BOOKS FOR IAS, ETC. OFFICERS 2. REGISTRATION RULES ETC. FOR SUB-REGISTRAR 3. POLICE LAW (WITH BOOKS) FOR POLICE OFFICERS 4. LAW PART-I (WITHOUT BOOKS) FOR COOPERATIVE OFFICERS. 5. ACCOUNTS (WITH BOOKS) FOR EXCISE OFFICERS. 6. GENERAL LAW PAPER-I (WITHOUT BOOKS) FOR LABOUR OFFICERS 7. LAW PAPER (WITH BOOKS) FOR OFFICERS OF LEGAL METROLOGY. TIME: 1.00 PM TO 4.00 PM 1. -

The First Mohammedan Invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa Took

The first Mohammedan invasion (1206 &1226 AD) of Kamrupa took place during the reign of a king called Prithu who was killed in a battle with Illtutmish's son Nassiruddin in 1228. During the second invasion by Ikhtiyaruddin Yuzbak or Tughril Khan, about 1257 AD, the king of Kamrupa Saindhya (1250-1270AD) transferred the capital 'Kamrup Nagar' to Kamatapur in the west. From then onwards, Kamata's ruler was called Kamateshwar. During the last part of 14th century, Arimatta was the ruler of Gaur (the northern region of former Kamatapur) who had his capital at Vaidyagar. And after the invasion of the Mughals in the 15th century many Muslims settled in this State and can be said to be the first Muslim settlers of this region. Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. According to popular Chutia legend, Chutia king Birpal established his rule at Sadia in 1189 AD. He was succeeded by ten kings of whom the eighth king Dhirnarayan or Dharmadhwajpal, in his old age, handed over his kingdom to his son-in-law Nitai or Nityapal. Later on Nityapal's incompetent rule gave a wonderful chance to the Ahom king Suhungmung or Dihingia Raja, who annexed it to the Ahom kingdom.Chutia Kingdom During the early part of the 13th century, when the Ahoms established their rule over Assam with the capital at Sibsagar, the Sovansiri area and the area by the banks of the Disang river were under the control of the Chutias. -

Bir Chilarai

Bir Chilarai March 1, 2021 In news : Recently, the Prime Minister of India paid tribute to Bir Chilarai(Assam ‘Kite Prince’) on his 512th birth anniversary Bir Chilarai(Shukladhwaja) He was Nara Narayan’s commander-in-chief and got his name Chilarai because, as a general, he executed troop movements that were as fast as a chila (kite/Eagle) The great General of Assam, Chilarai contributed a lot in building the Koch Kingdom strong He was also the younger brother of Nara Narayan, the king of the Kamata Kingdom in the 16th century. He along with his elder brother Malla Dev who later known as Naya Narayan attained knowledge about warfare and they were skilled in this art very well during their childhood. With his bravery and heroism, he played a crucial role in expanding the great empire of his elder brother, Maharaja Nara Narayan. He was the third son of Maharaja Biswa Singha (1523–1554 A.D.) The reign of Maharaja Viswa Singha marked a glorious episode in the history of Assam as he was the founder ruler of the Koch royal dynasty, who established his kingdom in 1515 AD. He had many sons but only four of them were remarkable. With his Royal Patronage Sankardeva was able to establish the Ek Saran Naam Dharma in Assam and bring about his cultural renaissance. Chilaray is said to have never committed brutalities on unarmed common people, and even those kings who surrendered were treated with respect. He also adopted guerrilla warfare successfully, even before Shivaji, the Maharaja of Maratha Empire did. -

Social Novel in Assamese a Brief Study with Jivanor Batot and Mirijiyori

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 06, 2020 SOCIAL NOVEL IN ASSAMESE A BRIEF STUDY WITH JIVANOR BATOT AND MIRIJIYORI Rodali Sopun Borgohain Research Scholar, Gauhati University, Assam, India Abstract : Social novel is a way to tell us about problems of our society and human beings. The social Novel is a ‘Pocket Theater’ who describe us about picture of real lifes. The Novel is a very important thing of educational society. The social Novel is writer basically based on social life. The social Novel “Jivonar Batot and Mirijiyori, both are reflect us about problems of society, thinking of society and the thought of human beings. Introduction : A novel is narrative work and being one of the most powerful froms that emerged in all literatures of the world. Clara Reeve describe the novel as a ‘Picture of real life and manners and of time in which it is writter. A novel which is written basically based on social life, the novel are called social novel. In the social Novels, any section or class of the human beings are dealt with. A novel is a narrative work and being one of the most powerful forms that emerged in all literatures of the world particularly during 19th and 20th centuries, is a literary type of certain lenght that presents a ‘story in fictionalized form’. Marion crawford, a well known American novelist and critic described the novel as a ‘pocket theater’, Clara Reeve described the Novel as a “picture of real life and manners and of time in which it is written”. -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

Notification

ASSAM PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION **** ADVT. NO.17/2016 No.3PSC/E-8/2016-17 Dated Guwahati, the 1st November /2016. NOTIFICATION It is hereby notified for information to all concerned Officers that the next Half Yearly Departmental Examination will be conducted by the Commission at Guwahati / Jorhat / Tezpur/ Silchar & Shillong. The Dates, Venues and Programme of the examination will be notified later on. As per Govt. letter communicated vide Memo No. HMA.46/2010/235-A, dated 13th October/2011, Officers in the rank of Inspector of Police are not permitted to appear in the Half Yearly Departmental Examination conducted by the Commission for IAS/IPS/ACS/APS etc. Officers till they are promoted to APS Junior Grade. Non-Gazetted Police Officer will appear at the examination to be held at the Headquarter of the District in which they are serving under supervision of a separate local Examination Board in each District, which shall be conducted simultaneously with the examination on Police Law and Languages of the Half Yearly Departmental Examination. The Officers who intend to appear at the Examination to be conducted by the Commission should download the Prescribed Form, viz: “Application Form for Half Yearly Departmental Examination,2016” from the Commission’s website www.apsc.nic.in and submit the filled in Application Form to the Secretary, Assam Public Service Commission, Jawaharnagar, Khanapara, Guwahati-22 through Deputy Commissioners, SDOs with intimation to the Govt. in the Personnel (A) Deptt. in case of IAS & ACS Officers and through their District/Sub- Divisional Heads under intimation to their Administrative Deptt. -

A Study of the Loans of the Princely State of Cooch Behar, 1863-1911

A Study of the Loans of the Princely State of Cooch Behar, 1863-1911 Tapas Debnath1 and Dr. Tahiti Sarkar2 1Research Scholar, Department of History, University of North Bengal 2Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of North Bengal Abstract: This article focuses on the loans of the Cooch Behar State especially the loans of Maharaja Nripendra Narayan. Cooch Behar became a protected State of the British in 1773. In the initial years of the British connection, Cooch Behar had some debts. After that, there was an increase in the savings of the State from 1864-1883. But the transfer of administration of the Cooch Behar State to Maharaja Nripendra Narayan in 1883 once again faced a shortfall in the State budget. The enormous development activities and personal expenses of Maharaja Nripendra Narayan created this situation. During his reign and afterward, the princely State of Cooch Behar was largely dependent on loans for the smooth running of the State. The British Government was very anxious to collect the debts from Cooch Behar. They wanted to control and reduce the personal expenditure of the Maharaja indirectly for the effective payment of the debts of the Cooch Behar State and the Maharaja. Maharaja Nripendra Narayan didn't control it entirely. After the death of Maharaja Nripendra Narayan, and apathy was seen in the attitude of the British Government to approve the large loan application of the Cooch Behar State from the British treasury. Keywords: Cooch Behar, Loan, Debt, Nripendra Narayan The British connection with Cooch Behar has established in 1773.1 The question, whether Cooch Behar was a native State or part of British Indian arose in 1873. -

A Case Study of the Tea Plantation Industry in Himalayan and Sub - Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000)

RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY BY SUPAM BISWAS GUIDE Dr. SHYAMAL CH. GUHA ROY CO – GUIDE PROFESSOR ANANDA GOPAL GHOSH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2015 JULY DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled RISE AND FALL OF THE BENGALI ENTREPRENEURSHIP: A CASE STUDY OF THE TEA PLANTATION INDUSTRY IN HIMALAYAN AND SUB - HIMALAYAN REGION OF BENGAL (1879 – 2000) has been prepared by me under the guidance of DR. Shyamal Ch. Guha Roy, Retired Associate Professor, Dept. of History, Siliguri College, Dist – Darjeeling and co – guidance of Retired Professor Ananda Gopal Ghosh , Dept. of History, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. Supam Biswas Department of History North Bengal University, Raja Rammuhanpur, Dist. Darjeeling, West Bengal. Date: 18.06.2015 Abstract Title Rise and Fall of The Bengali Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of The Tea Plantation Industry In Himalayan and Sub Himalayan Region of Bengal (1879 – 2000) The ownership and control of the tea planting and manufacturing companies in the Himalayan and sub – Himalayan region of Bengal were enjoyed by two communities, to wit the Europeans and the Indians especially the Bengalis migrated from various part of undivided Eastern and Southern Bengal. In the true sense the Europeans were the harbinger in this field. Assam by far the foremost region in tea production was closely followed by Bengal whose tea producing areas included the hill areas and the plains of the Terai in Darjeeling district, the Dooars in Jalpaiguri district and Chittagong. -

About the Koch Rajbanshi

ABOUT THE KOCH RAJBANSHI Photo: Linkan Roy Various legends trace the origin of the Koch Rajbanshi in Siberia region and its affinity with communities like Lepcha and Dimasa. Considered as indigenous people of South Asia, at present they live in lower of Nepal, Northern of Bengal, North Bihar, Northern Bangladesh, whole of Assam, parts Meghalya and Bhutan. These modern geographical areas were once part of the Kamata kingdom ruled by the Koches for many centuries. The Koches also started calling themselves as Rajbanshi to keep connected with their royal lineage of Koch Dynasty of Kamata. Koch Rajbanshis have gone through many social and cultural changes through the centuries and have become an inclusive social category in which many other groups have joined. The transformation of the “Koch” tribal society into the “Koch Rajbanshi” nation is a unique phenomenon. At present when we refer about the Koch Rajbanshi, we actually refer to an inclusive social group, rather than an exclusive community. Koch Rajbanshis are largely Hindus with lots of their own deities and rituals. A large section of Koch Rajbanshi became follower of Islam and the present Muslims of North Bengal, West Assam and Northern Bangladesh known as “Deshi Mushalman” are of Koch Rajbanshi origin. There are also Christian and Buddhist Koch Rajbanshis. During the expansion of the Koch Kamata Empire, Koch Rajbanshi took the initiate of creating a common culture and a common language in the region which is at present popularly termed as Kamatapuri. Small sections of the Koch Rajbanshi people have successfully preserved the Tibeto-Burman Koch language and culture. -

Role of the Cooch Behar State Regency Council (1922 - 1936)

Karatoya: NBU J. Hist. Vol. 6 :70-84 (2013) ISSN: 2229-4880 Role of the Cooch Behar State Regency Council (1922 - 1936) Joydeep Pai* .. The history of British India is mainly indicated the formation of Paramountcy in the Princely States of India. During the first half of the 19th century one of the policy of the British Government was the implementation of the indirect rule. For that purpose .. British Government introduced the system of Regency Council in the Princely States. Regency Council is a person or group of person selected to act as the head of the State when the ruler is minor or not present or debilitated. The period of a regent or regents is referred to as regency. Cooch Behar, the tiny Princely State in North - Eastern India is not an exception of that. The geographical location of the State interested the British Government to take some measures in this regard. However, the administration of the Princely State of Cooch Behar found a new dimension from I 863. Here it deserve to mention that after the death of Maharaja Harendra Narayan in 1839, the Colonial Government had the free run in the State. The successor, Maharaja Shivendra Narayan had a pro- British attitude. Therefore, when he ascended the throne, it helped the British Government to fulfi ll their designs. So, the policy of indirect rule found its strong foothold in Cooch Behar. After that the British helped the Maharaja in all avenues of administration. Regarding smooth running of the State there were broad lines of the British administration for Cooch Behar during the minority of the Maharaja and the general principles of the British Government adopted by the State, was a beneficial scheme for the smooth running of the State. -

Unit 23 Central and Eastern India

.UNIT 23 CENTRAL AND EASTERN INDIA Objectives Introduction Malwa Jaunpur Bengal Assam 23.5.1 Kamata-Kamrup 23.5.2 The Ahoms Orissa Let Us sum UP Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 4 23.0 OBJECTIVES In the present Unit, we will study about regional states in Central and Eastern India during the 13-15th centuries. After reading this Unit, you would learn about: the emergence of regional states in Central and Eastern India, territorial expansion of these regional kingdoms, their relations with their neighbours and other regional states, and 1 their relations with the Delhi Sultanate. 23.4 INTRODUCTION You have already read (in Block 5, Unit 18) that regional kingdoms posed severe threat to the already weakened Delhi Sultanate and with their emergence began the process of the physical disintegration of the Sultanate. In this Unit, our focus would be on the emergence of regional states in Central and Eastern India viz., Malwa, Jaunpur, Bengal, Assam and Orissa. We will study the polity-establishment, expansion and disintegration-of the above kingdoms. You would know how they emerged and succeeded in establishing their hegemony. During the 13th-15th centuries in Central and Eastern India, there emerged two types of kingdoms: a) those whose rise and development was independent of the Sultanate (for example : the kingdoms of Assam and Orissa) and b) Bengal, Malwa and Jaunpur who owed tHeir existencr ru the Sultanate. All these kingdoms were constantlyat war with each other. The nobles, ci,' ;s or rajas and local aristocracy played crucial roles in these confrontations. 23.2 MALWA The decline of the Sultanate paved the way for the emergence bf the independent kingdom of Malwa. -

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY of the REGION Ahom

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY OF THE REGION Ahom and Assam are inter-related terms. The word Ahom means the SHAN or the TAI people who migrated to the Brahma putra valley in the 13th Century A.D. from their original homeland MUNGMAN or PONG situated in upper Bunna on the Irrawaddy river. The word Assam refers to the Brahmaputra valley and the adjoining areas where the Shan people settled down and formed a kingdom with the intention of permanently absorbing in the land and its heritage. From the prehistoric period to about 13th/l4 Century A.D. Assam was referred to as Kamarupa and Pragjyotisha in Indian literary works and historical accounts. Early Period ; Area and Jurisdiction In the Ramayana and Mahabharata and in the Puranik and Tantrik literature, there are numerous references to ancient Assam, which was known as Pragjyotisha in the epics and Kamarupa in the Puranas and Tantras. V^Tien the stories related to it inserted in the Maha bharata, it stretched southward as far as the Bay of Bengal and its western boundary was river Karotoya. This was then a river of the first order and united in its bed the streams which now form the Tista, the Kosi and the Mahanada.^ 14 15 According to the most of the Puranas dealing with geo graphy of the earlier period, the kingdom extended upto the river Karatoya in the west and included Manipur, Jayantia, Cachar, parts of Mymensing, Sylhet, Rangpur and portions of 2 Bhutan and Nepal. The Yogini Yantra (V I:16-18) describes the boundary as - Nepalasya Kancanadrin Bramaputrasye Samagamam Karotoyam Samarabhya Yavad Dipparavasinara Uttarasyam Kanjagirah Karatoyatu pascime tirtharestha Diksunadi Purvasyam giri Kanyake Daksine Brahmaputrasya Laksayan Samgamavadhih Kamarupa iti Khyatah Sarva Sastresu niscitah.