A Survey on the Unique & Composite Temples of Cooch Behar From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duare Sarkar Camp Location (Phase -I) in Cooch Behar District

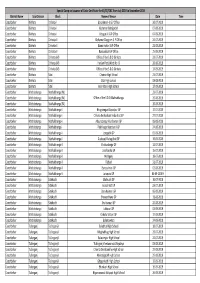

Duare Sarkar Camp Location (Phase -I) in Cooch Behar district Camp Date Block/Municipality(M) Gram Panchayat / Ward Venue 01/12/2020 Cooch Behar (M) Ward - 001 Rambhola High School Cooch Behar (M) Ward - 002 Rambhola High School Cooch Behar-1 Putimari-Fuleswari Paitkapara Ap School Cooch Behar-2 Gopalpur Gopalpur High School Dinhata-1 Gosanimari-I Gosanimari High School Dinhata-1 Gosanimari-II Gosanimari Rajpath Primary School Dinhata-2 Chowdhurihat Chowdhurihat Vivekananda Vidyamandir Dinhata-2 Sukarukuthi Sukarukuthi High School Haldibari Uttar Bara Haldibari Kaluram High School Mathabhanga-1 Gopalpur Gopalpur Pry. School Mathabhanga-2 Angarkata-Pardubi A.K.Paradubi High School Mekhliganj Ranirhat Alokjhari High School Sitai Adabari Konachata High School Sitalkuchi Chhotosalbari Sarbeswarjayduar No. 1 Pry. School Tufanganj-1 Natabari-I Natabari High School Tufanganj-2 Bhanukumari-I Boxirhat Jr. Basic School 02/12/2020 Cooch Behar (M) Ward - 003 Netaji Vidyapith Cooch Behar (M) Ward - 005 Netaji Vidyapith Cooch Behar-1 Chandamari Prannath High School Dinhata-1 Matalhat Matalhat High School Dinhata-1 Petla Nabibaks High School Haldibari Boxiganj Boxiganj Abdul Kader High School Mathabhanga (M) Ward - 001 Mathabhanga Vivekananda Vidyamandir Mathabhanga (M) Ward - 012 Mathabhanga Vivekananda Vidyamandir Mathabhanga-1 Kedarhat Jorshimuli High School Mathabhanga-2 Nishiganj-I Nishiganj Nishimoyee High School Tufanganj-1 Natabari-Ii Bhelapeta High School Tufanganj-2 Bhanukumari-Ii Joraimore Community Hall 03/12/2020 Cooch Behar (M) Ward - -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

Sundakphu Trek – Darjeeling

Sundakphu Trek – Darjeeling Sandakphu trek is beautified by the local villages of Darjeeling district and Nepal. It’s a border line trek between India and Nepal, and we keep swinging between the regions and villages of Nepal and India. The best part of it is, its an easy trek and considered the best of the Himalayan routes to start a multi-day trek in the Himalayas. Sandakphu at 3636 meters is also the highest point of West Bengal - India. No other treks in India can boast of what Sandakphu Phalut trek can offer. The view from Sandakphu is unsurpassed by any view anywhere with grand views of four of the World's highest 8000 meter peaks - Mt. Everest (8850m, 1st), Kanchenjunga (8586m, 3rd), Mt. Lhotse (8516m, 4th) and Makalu (8481m, 5th). Duration: 11 days Highest Altitude: 3636 M Sandakphu Best Time: Jan to May, Oct to Dec Terrain: Rhododendron forest, alpine meadows, rocky Activity Type: Trek, camping and Photography Grade: Easy Starts At: Maneybhanjyang Ends At: Srikhola Region: India - Darjeeling West Bagnoli Generic Food Menu: Indian, Nepalese, Tibetan Route: Delhi – Bagdogra – Darjeeling – Maneybhanjang - Tumling - Kalipokhari – Sandakphu - Phalut – Gorkhey - Rimbick – Darjeeling - Bagdogra - Delhi [email protected] +911141322940 www.shikhar.com Detailed Itinerary: - Day 1: Sat. 16 Feb 2019 Rishikesh - Delhi Meet Shikhar travels representative at your hotel and drive or take a train to Delhi. Upon arrival check in the hotel. Overnight stay in Delhi. Meals: N/A Day 02: Sun. 17 Feb’19 Delhi – Bagdogra - Darjeeling Flight & Drive Morning after breakfast transfer to domestic airport to board flight to Bagdogra. -

7-Day Singalila Ridge / Sandakphu Trek Tour Code: IND-SRS 07

7 7-Day Singalila Ridge / Sandakphu Trek Tour Code: IND-SRS_07 An easy but rewarding trek which offers spectacular views of the big mountains Grading including Everest and Kanchenjunga. This trek traverses along the Singalila ridge Easy Trek which forms the international border line between India and Nepal. It offers a At a glance good distant view of Mt. Everest (8850 m) accompanied by Lhotse (8501m) and • 05 days of trekking Makalu (8475m) and a close view of Kanchenjunga (8586m). Kanchenjunga • 04 nights in along with the surrounding ranges closely resembles a person sleeping and hence trekker's hut the view from Sandakphu is popularly called 'The Sleeping Buddha'. The Singalila • 02 hotels nights in ridge is actually an extension of one of the ridges that sweep down from the high Darjeeling snows of Kanchenjunga itself and the trek along this ridge is renowned as being Places Visited one of the most scenically rewarding in the entire Himalayas. This area is also • Darjeeling Departure culturally diverse, with Tibetan, Mongolian, and Indians intermixed with 22 Feb-28 Feb, 2015 immigrant Nepalese. Buddhism is the most popular religion and during the course 15 Mar-21 Mar, 2015 of our trip there's immense chance of interaction with the warm locals at 12 Nov-18 Nov, 2015 Trekker's Hut that dot this trail. Quick Itinerary: Day 01: Bagdogra to Darjeeling (2134m) Day 02: Drive Darjeeling to Dhotrey (2460m) and trek to Tonglu (3070m) 2.5 hr drive and 3 hrs trek Day 03: Trek to Kalapokhri (3108m) 6 hrs trek Day 04: Trek to Sandakphu (3636m) 3 hrs trek Day 05: Trek to Gurdum (2400m) 3-4 hrs Day 06: Trek to Sepi (2280m) 3 hrs and drive 4 hrs to Darjeeling Day 07: Drive to Bagdogra 3 hrs X-Trekkers Adventure Consultant Pte Ltd (TA License: 01261) Co. -

Howrah, West Bengal

Howrah, West Bengal 1 Contents Sl. No. Page No. 1. Foreword ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 2. District overview ……………………………………………………………………………… 5-16 3. Hazard , Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis a) Seasonality of identified hazards ………………………………………………… 18 b) Prevalent hazards ……………………………………………………………………….. 19-20 c) Vulnerability concerns towards flooding ……………………………………. 20-21 d) List of Vulnerable Areas (Village wise) from Flood ……………………… 22-24 e) Map showing Flood prone areas of Howrah District ……………………. 26 f) Inundation Map for the year 2017 ……………………………………………….. 27 4. Institutional Arrangements a) Departments, Div. Commissioner & District Administration ……….. 29-31 b) Important contacts of Sub-division ………………………………………………. 32 c) Contact nos. of Block Dev. Officers ………………………………………………… 33 d) Disaster Management Set up and contact nos. of divers ………………… 34 e) Police Officials- Howrah Commissionerate …………………………………… 35-36 f) Police Officials –Superintendent of Police, Howrah(Rural) ………… 36-37 g) Contact nos. of M.L.As / M.P.s ………………………………………………………. 37 h) Contact nos. of office bearers of Howrah ZillapParishad ……………… 38 i) Contact nos. of State Level Nodal Officers …………………………………….. 38 j) Health & Family welfare ………………………………………………………………. 39-41 k) Agriculture …………………………………………………………………………………… 42 l) Irrigation-Control Room ………………………………………………………………. 43 5. Resource analysis a) Identification of Infrastructures on Highlands …………………………….. 45-46 b) Status report on Govt. aided Flood Shelters & Relief Godown………. 47 c) Map-showing Govt. aided Flood -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

1543927662BAY Writte

_, tJutba ~arbbaman .liUa JJari~bab Court Compound, Bardhaman-713101 zp [email protected] Tel: 0342-2662400 Fax-0342-2663327 Memo No :- 2() 9 a IPBZP Dated, 04/l2./2018 From :- Deputy Secretary, Purba Bardhaman Zilla Parishad To: District Information Officer, Purba Bardhaman Sir, Enclosed please find herewith the list of candidates eligible to appear in the written examination for the recruitment to post of District Coordinator & Technical Assistant on the is" December, 2018 from 10:00 AM. You are requested to upload the same official website of Purba Bardhaman. Deputy Secretary, Purba Bardhaman Zilla Parishad MemoNo :- QS.,o !3/PBZP Dated, 4 I J 2./2018 Copy forwarded for information and necessaryaction to :- I) DIA, Purba Bardhaman Zilla Parishad for wide circulation through Zilla Parishadwebsite II) CA to District Magistrate, Purba Bardhaman for kind perusal of the DM. Purba Bardhaman. III) CA to Additional Executive officer, Purba Bardhaman Zilla Parishad for kind perusal of the AEO. Purba Bardhaman Zilla Parishad . Deputy Secretary, Purba Bardhaman Zilla Parishad E:\.6.rjun important files\IAY-communication-17-18_arjun updated.docx Father 51 Apply for Name Name/Husband/Guard ViII / City PO P5 District PIN No the Post ian's 85-Balidanga, District Co- Purba 1 Arnab Konar Prasanta kr. Konar Nazrulpally Sripally Burdwan Sadar 713103 ordinator Bardhaman Boronipur District Co- Purba 2 Partha Kumar Gour Chandra Kumar Jyotchilam Bolpur Raina 713103 ordinator Bardhaman District Co- Purba 3 Sraboni Pal Mondal Mahadeb Mondal Askaran Galsi Galsi 713406 ordlnator Bardhaman District Co- Patuli Station Purba 4 Dhrubajyoti Shil Sunil Kumar Shil Patuli Station Bazar Purbasthali 713512 ordinator Bazar Bardhaman District Co- Lakshmi Narayan Paschim 5 Antu 5arkar Khandra Khandra Andal 713363 ordinator Sarkar Bardhaman District Co- Purba 6 Sk Amiruddin Sk Johiruddin East Bardhaman Bardhaman Bardhaman 713101 ordinator Bardhaman District Co- Purba 7 Sujit Malik Lt. -

38 Chapter-Ii Geographical

CHAPTER-II GEOGRAPHICAL BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY AREA 2.1. Introduction: Study Area is the prime concern of any research especially in a spatial science like Geography. It is the place, based on which, the researcher carries out in-depth study and data collection. A discussion on the study area is fundamental as it helps in understanding the contextual background of the area under investigation. Mead defined study area as “the geographical studies pursued in a well-defined area” (Mead, 1969). Generally, a research is conducted within or beyond an area delimited by political or physical boundaries. However, it is sometimes difficult to delineate a study area as it may stretch beyond either of the boundaries. The study area is the geographic framework within which the field work is conducted, and thus its exact areal extent must be determined to focus and further define the purposes of the research. As the present research is based on the Geo-environmental study of the wetlands of Tufanganj and Koch Bihar Sadar subdivisions within Koch Bihar District, the study area and subsequent data collection have been confined to four community development blocks, namely Tufanganj-I, Tufanganj-II, Koch Bihar-I and Koch Bihar-II. Thus the main focus of the present chapter is on the historical background, physical and socio-economic background as well as the administrative jurisdiction and geographic location of Koch Bihar District. 2.2. Historical Background: Etymologically, ‘Koch Bihar’ or ‘Cooch Behar’ has been derived from two words- ‘Cooch’ and ‘Behar’. While the word ‘Cooch’ is a corrupted form of the word ‘Koch’ that signifies an indigenous mongoloid tribe, the word ‘Behar’ is derived from Sanskrit word ‘Vihara’, which means ‘abode’, or ‘sport’. -

Paradise Point TOURISM

TOURISM UPDATE SANDAKPHU Colour Burst: In spring, Nature greets visitors with a variety of rhododendrons, orchids and giant magnolias in full bloom. Room with a View: The vantage point at Sandakphu which promises the best view of the Everest range. Road to Heaven: A narrow trekking route winding up the mountain path seems to vanish abruptly from the edge of the mountain into the vast sky beyond. ta H E V M A BH AI BY V S O T PHO Paradise Point For the best view of four of the five highest peaks in the world and the adventure of a lifetime BY RAVI SAGAR Located to the northwest of Darjeeling town, the head to Sandakphu. trek to Sandakphu packs one memorable adven- andakphu may not ring a bell for many travellers. But for the ture. This 32 km adventure trail along the Singalila inveterate adventure seeker or the bona fide trekker, it is the Range is actually considered a beginner’s trek, the ultimate destination. Tucked away in the eastern edge of India best place for a first-time adventure tourist to begin. in the Darjeeling district of West Bengal is this tiny hamlet atop One of the most beautiful terrains for trekking, the the eponymous peak, the highest peak in the state. So what best time for the Sandakphu experience is April- Smakes Sandakphu so special? May (spring) and October-November (post mon- The climb to the highest point of this hill station situated at an altitude soon). But the stark beauty of snow-covered Sanda- of 3,636m promises you a sight that will leave you gasping. -

Republic Darjeeling Black Tea the Champagne of Teas

REPUBLIC DARJEELING BLACK TEA THE CHAMPAGNE OF TEAS Founded in 1992, The Republic of Tea sparked a Tea Revolution. We began by canvassing the most prized tea gardens of the world for their worthiest leaves. Our collection of premium glass bottle iced teas are all unsweetened, contain zero calories and are free of any artificial flavors or colors. • Gluten-free and Orthodox Union Kosher certifi ed. • Glass bottle contains 500mL (16.9 fl .oz.) and fi lls more than two glasses over ice. FOOD PAIRINGS: Shellfi sh, hors d’oeuvres, veal, lamb DESSERTS: Chocolates TASTE: Pure, organic black tea with muscat grape notes BODY: Light NOTES: Clear, bright and invigorating, this tea presents a rich, flowery and elegant finish. All the flavor and aroma of a prized Darjeeling, the “Champagne” of Teas. THE #1 BOTTLED ICED TEA IN AMERICA’S FINEST RESTAURANTS 5 Hamilton Landing, Suite 100 • Novato, CA 94949 • T: 800.298.4TEA • F: 800.257.1731 • www.R.com • E printed on recycled paper 5 Hamilton Landing, Suite 100 • Novato, CA 94949 • T: 800.298.4TEA • F: 800.257.1731 www.R.com • printed on recycled paper Darjeeling_Sellsheet_5x7.indd 1 2/16/18 10:43 AM Producing The Champagne of Teas, The Darjeeling Region of West Bengal, India. As Champagne grapes from the Champagne region of France are exclusively used for French sparkling wines, Darjeeling teas, the Champagne of teas, use only the fi nest tea leaves from the Darjeeling Region of India. Located on the foothills of Himalayas, these tea gardens are located at altitudes of up to 4000 feet above sea level, where the soil is slightly acidic. -

Travel Guide - Page 1

Darjiling Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/darjiling page 1 delicious Sikkimese and Tibetan cuisines, Max: 15.0°C Min: Rain: 6.400000095 197.199996948242 experience the Tibetan Buddhist culture and 367432°C 2mm Darjiling take home the beautiful handicrafts made Jun Darjeeling is a lush green hill town by the locals. Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, umbrella. in West Bengal, famous for its tea Max: 16.5°C Min: Rain: 570.0mm plantations. Developed by the 9.800000190 734863°C British in the 19th century, this Jul serene town is now home to the When To Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, vibrant Tibetan and Sikkimese umbrella. cultures. Hop on to the quiet Max: Min: Rain: VISIT 16.89999961 11.39999961 781.700012207031 Himalayan Railway to experience 8530273°C 8530273°C 2mm some of the most breathtaking http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-darjiling-lp-1050317 Aug views of the majestic Himalayas on Famous For : Weekend GetawaysCity Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, umbrella. your journey. Padmaja Naidu Jan Max: Min: 9.5°C Rain: Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Himalayan Zoological Park, Ghoom 16.89999961 635.299987792968 Max: Min: 3.0°C Rain: 8530273°C 8mm Monastery, Peace Pagoda, Tenzing Darjeeling is synonymous with sprawling 5.599999904 19.7000007629394 Sep Rock, Japanese Buddhist Temple green and picturesque tea-estates. Tea 632568°C 53mm Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen, and Happy Valley Tea Estate are production in Darjeeling is a legacy of the Feb umbrella. British, who developed the place as a hill Very cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. -

Sub-Division

Special Camp on issuance of Caste Certificate for SC/ST/OBC from July 2019 to September 2019 District Name Sub-Division Block Name of Venue Date Time Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata-I Gosanimari-II G.P Office 30-07-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata-I Kishamar Batrigachh 07-08-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata-I Vetaguri-II G.P Office 04-09-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata-II Kishamar Dasgram G.P Office 24-07-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata-II Bamanhata-I G.P Office 21-08-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata-II Barasakdal G.P Office 25-09-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata (M) Office of the S.D.O Dinhata 23-07-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata (M) Harijan Patti,Ward No -9 28-08-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Dinhata (M) Office of the S.D.O Dinhata 17-09-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Sitai Chamta High School 23-07-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Sitai Sitai High school 08-08-2019 Coochbehar Dinhata Sitai Keshribari High School 17-09-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga (M) 23-07-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga (M) Office of the S.D.O Mathabhanga 20-08-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga (M) 19-09-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga-I Bhogramguri Gopalpur GP 17-07-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga-I Chhoto Kesharibari Kedarthat GP 27-07-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga-I Abasratanpur Kurshamari GP 09-08-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga-I Pakhihaga Hazrahat-I GP 24-08-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga-I Jorepatki GP 05-09-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga-I Duaisuai, Bairagirhat GP 19-09-2019 Coochbehar Mathabhanga Mathabhanga-II