Biographies, Research, Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Bulletin Volume 30 No

American Association of Teachers of French NATIONAL BULLETIN VOLUME 30 NO. 1 SEPTEMBER 2004 FROM THE PRESIDENT butions in making this an exemplary con- utility, Vice-President Robert “Tennessee ference. Whether you were in attendance Bob” Peckham has begun to develop a Web physically or vicariously, you can be proud site in response to SOS calls this spring of how our association represented all of and summer from members in New York us and presented American teachers of state, and these serve as models for our French as welcoming hosts to a world of national campaign to reach every state. T- French teachers. Bob is asking each chapter to identify to the Regional Representative an advocacy re- Advocacy, Recruitment, and Leadership source person to work on this project (see Development page 5), since every French program is sup- Before the inaugural session of the con- ported or lost at the local level (see pages 5 ference took center stage, AATF Executive and 7). Council members met to discuss future A second initiative, recruitment of new initiatives of our organization as we strive to members, is linked to a mentoring program respond effectively to the challenges facing to provide support for French teachers, new Atlanta, Host to the Francophone World our profession. We recognize that as teach- teachers, solitary teachers, or teachers ers, we must be as resourceful outside of We were 1100 participants with speak- looking to collaborate. It has been recog- the classroom as we are in the classroom. nized that mentoring is essential if teach- ers representing 118 nations, united in our We want our students to become more pro- passion for the French language in its di- ers are to feel successful and remain in the ficient in the use of French and more knowl- profession. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

"Red Emma"? Emma Goldman, from Alien Rebel to American Icon Oz

Whatever Happened to "Red Emma"? Emma Goldman, from Alien Rebel to American Icon Oz Frankel The Journal of American History, Vol. 83, No. 3. (Dec., 1996), pp. 903-942. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723%28199612%2983%3A3%3C903%3AWHT%22EE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B The Journal of American History is currently published by Organization of American Historians. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oah.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Download As a PDF File

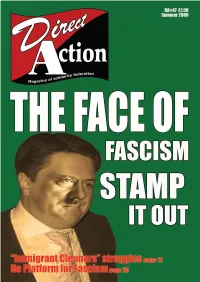

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

Together We Will Make a New World Download

This talk, given at ‘Past and Present of Radical Sexual Politics’, the Fifth Meeting of the Seminar ‘Socialism and Sexuality’, Amsterdam October 3-4, 2003, is part of my ongoing research into sexual and political utopianism. Some of the material on pp.1-4 has been re- used and more fully developed in my later article, Speaking Desire: anarchism and free love as utopian performance in fin de siècle Britain, 2009. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. ‘Together we will make a new world’: Sexual and Political Utopianism by Judy Greenway By reaching for the moon, it is said, we learn to reach. Utopianism, or ‘social dreaming’, is the education of desire for a better world, and therefore a necessary part of any movement for social change.1 In this paper I use examples from my research on anarchism, gender and sexuality in Britain from the 1880s onwards, to discuss changing concepts of free love and the relationship between sexual freedom and social transformation, especially for women. All varieties of anarchism have in common a rejection of the state, its laws and institutions, including marriage. The concept of ‘free love' is not static, however, but historically situated. In the late nineteenth century, hostile commentators linked sexual to political danger. Amidst widespread public discussion of marriage, anarchists had to take a position, and anarchist women placed the debate within a feminist framework. Many saw free love as central to a critique of capitalism and patriarchy, the basis of a wider struggle around such issues as sex education, contraception, and women's economic and social independence. -

Baixa Descarrega El

Jacqueline Hurtley and Elizabeth Russell Universitat de Barcelona and Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona Following the fruits of the second wave of feminism fiom the 60s into the 80s, the backlash has set in (cf. Susan Faludi), with texts such as Camille Pagha's Sexual Personae intensqing the reaction. Beyond the women's movemenf we are witnesses to a growing sense of intolerante, made manifest in xenophobic attitudes and racist attacks. In The Nature of Fascism, published in 1991, Roger Grifñn spends his fúst chapter dwelling on the "conundrum" of fascism, so temed because of the lack of consensus as to how fascism might be defined. We do not propose to consider the complexities involved here but will rnake use of Griíñn's working definition: "Fascism is a genus of political ideology whose mythc core in its various permutations is a pahgenetic fom of populist ultranationalism." (Grif6n 1991,26). For our particular purpose, we wish to focus on the concept of palingenesis (fkom palin - again, anew; and genesis - creation, biríh). Fascism promulgated the idea of rebiríh: the movement would bring about "a new national community", one which would draw on, " - where posible, traditions which had supposedly remained uncontaminated by degenerative forces and whose cohesion was assured by new institutions, organisations and practices based on a new political hierarchy and a new heroic ethos" (Griíñn 1991, 45). Women became conspicuous by their absence within the new phallocentnc hierarchy. The new fascist man (hornofmcistus) wodd be intent on saaiñcing himseíf to the higher needs of the nation. In Male Fantasies Klaus Theweleit drew on case-studies produced on a number of individuals who played an active part in German proto-fascism. -

New Anarchist Review Advertising in the Newanarchist Review June 1985, While on Their C/O 84B Whitechapel High Street Costs from £10 a Quarter Page

i 3 Balmoral Place Stirling, Scotland For trade distribution contact FK8 2RD 84b Whitechapel High Street London E1 7QX M A I L OR D E R Tel/fax 081 558 7732 DISTRIBUTION R iii-'\%1[_ X6%LE; 1/ ‘3 _|_i'| NI Iii O ‘Puxlci-IUi~lF G %*%ad,J\..1= BLACK _..ni|.miu¢ _ RED I BLQCK ... Rnmcho-lymhcufld *€' BREEN a BLMIK.....iiiuachv-Queen ,1-\ Plianchmle 5;7P%""¢5 L0 ..,....0u ab»! ’____ : <*REE"--I-=~‘~siw mi. Punchline *8: Let us Pray "'""~" 9"" Punchline *9: Time to remove GREEN 5 PURPLE.....Uc.ncn4 Jufflu N TFllAI\IGl_ESRq, ____, ,,,,,,,,,, Punchline ,10: Censorship oi bi"EEl'L ,,,l -znwiuli 8 $g?L":]":' """*'”"‘ L?;LB5"£5"";" Each copy £1 (post pai'd) in UK. M, ,,'f,‘;,'1;¢.5 are 11 30 Mm European orders £1.20 (post paid) mmoguijifgmflgrmfj, Mme European wholesale welcome Make cheques payable to ‘J Elliott’ only. Big Bang, Plain Wrapper comix, Punchline, Fixed Grin, Anti Shirts Catalogue from: BM ACTIVE LONDON WC1 N 3XX, LONDO 1M1Nflilllillilfilll __-rwuew ANARCH‘: ' ' '1... l'|1W ANARCHIST REVIEW NEW TITLES These titles are available from A Distribution (trade) counts what happened to No. 21 S September 1992 and AK Press (mail order) unless otherwise stated. several hundred travellers, See back page for addresses. who were attacked in a mili- Published by: Advertise taiy-style police operation in New Anarchist Review Advertising in the NewAnarchist Review June 1985, while on their c/o 84b Whitechapel High Street costs from £10 a quarter page. Series ANARCHY BY AN druggists’, or hard by a win- way to the Stonehenge festi- London E1 7QX discounts available. -

Revolution by the Book

AK PRESS PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2009 AKFRIENDS PRESS OF SUMM AK PRESSER 2009 Friends of AK/Bookmobile .........1 Periodicals .................................51 Welcome to the About AK Press ...........................2 Poetry/Theater...........................39 Summer Catalog! Acerca de AK Press ...................4 Politics/Current Events ............40 Prisons/Policing ........................43 For our complete and up-to-date AK Press Publishing Race ............................................44 listing of thousands more books, New Titles .....................................6 Situationism/Surrealism ..........45 CDs, pamphlets, DVDs, t-shirts, Forthcoming ...............................12 Spanish .......................................46 and other items, please visit us Recent & Recommended .........14 Theory .........................................47 online: Selected Backlist ......................16 Vegan/Vegetarian .....................48 http://www.akpress.org AK Press Gear ...........................52 Zines ............................................50 AK Press AK Press Distribution Wearables AK Gear.......................................52 674-A 23rd St. New & Recommended Distro Gear .................................52 Oakland, CA 94612 Anarchism ..................................18 (510)208-1700 | [email protected] Biography/Autobiography .......20 Exclusive Publishers CDs ..............................................21 Arbeiter Ring Publishing ..........54 ON THE COVER : Children/Young Adult ................22 -

Anarchists in the Late 1990S, Was Varied, Imaginative and Often Very Angry

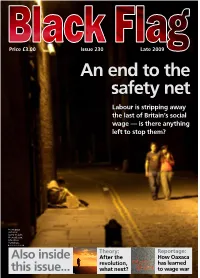

Price £3.00 Issue 230 Late 2009 An end to the safety net Labour is stripping away the last of Britain’s social wage — is there anything left to stop them? Front page pictures: Garry Knight, Photos8.com, Libertinus Yomango, Theory: Reportage: Also inside After the How Oaxaca revolution, has learned this issue... what next? to wage war Editorial Welcome to issue 230 of Black Flag, the fifth published by the current Editorial Collective. Since our re-launch in October 2007 feedback has generally tended to be positive. Black Flag continues to be published twice a year, and we are still aiming to become quarterly. However, this is easier said than done as we are a small group. So at this juncture, we make our usual appeal for articles, more bodies to get physically involved, and yes, financial donations would be more than welcome! This issue also coincides with the 25th anniversary of the Anarchist Bookfair – arguably the longest running and largest in the world? It is certainly the biggest date in the UK anarchist calendar. To celebrate the event we have included an article written by organisers past and present, which it is hoped will form the kernel of a general history of the event from its beginnings in the Autonomy Club. Well done and thank you to all those who have made this event possible over the years, we all have Walk this way: The Black Flag ladybird finds it can be hard going to balance trying many fond memories. to organise while keeping yourself safe – but it’s worth it. -

Rebelworker-37-2-Aug-Sep-2019

Sydney, Australia Paper of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Network 50c Vol.37 No.2 (225) Aug -Sept. 2019 WHY NOT A 2 HOUR STOPPAGE TO SUPPORT THE GLOBAL CLIMATE ACTION STRIKE 20TH SEPT? WORKERS & UNIONISTS MUST SUPPORT EFFORTS TO SAVE THE PLANET! THERE WILL BE NO JOBS ON A DEAD PLANET! AMAZON WORKERS’ INTERNATIONAL STRIKE P2; NSW RAILWAY NEWS P3; FAIR GAME PART (1) P5; THE 6 EMOTIONS THE BOSS USE AGAINST YOU P6; PERCEPTIONS OF WORKERS’ RIGHTS P6; SYNDEY BUSES NEWS P7; VICTORIAN RAILWAY NEWS P9; BRITAIN TODAY P10; FRANCE: YELLOW VESTS P12; USA: UBER & THE GIG ECONOMY P14; BOOK REVIEW P15; EDGARD LEUENROTH 1881-1968 P18 BULGARIA P18; USA: BURGER WORKERS’ STRIKE P20; 2 Rebel Worker line database that ICE agents use to track Items arrive already packaged from fa- Rebel Worker is the bi-monthly immigrants they are trying to deport. The cilities further up the supply chain, in- Paper of the A.S.N. for the propa- New York City rally was held at CEO Jeff cluding fulfilment centres like the one in gation of anarcho-syndicalism in Bezos’s $80 million mega-penthouse. Minnesota. Workers in delivery centres Australia. Minneapolis to Chicago sort the packages and load them into The fulfilment centre in Shakopee, a vans for delivery. These facilities have Unless otherwise stated, signed proliferated in major urban centres as Articles do not necessarily represent suburb of Minneapolis, has been the site of some of the most confrontational and part of the push for one-day and the position of the A.S.N. as a whole. -

Socialism, Internationalism and Zionism: the Independent Labour Party and Palestine, C.1917–1939

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Simpson, Paul (2020) Socialism, internationalism and Zionism: the independent Labour Party and Palestine, c.1917–1939. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/44090/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html SOCIALISM, INTERNATIONALISM AND ZIONISM: THE INDEPENDENT LABOUR PARTY AND PALESTINE, C. 1917–1939 P.T. SIMPSON PhD 2020 0 Socialism, Internationalism and Zionism: The Independent Labour Party and Palestine, c. 1917–1939 Paul T. Simpson Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research Undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sciences May 2020 1 Abstract Using the Independent Labour Party (ILP) as its case study, this thesis examines the relationship between the labour movement’s interpretations of internationalism and its attitudes towards Zionism during the interwar years. -

Cinquant'anni Di Volontà Indici 1946-1996 a Cura Di Dario Bernardi E Luciano Lanza Nota Introduttiva Durante I Decenni Di Pu

Cinquant’anni di Volontà Indici 1946-1996 a cura di Dario Bernardi e Luciano Lanza Nota introduttiva Durante i decenni di pubblicazione, e con il rotare di redazioni e responsabili, ovviamente le norme di scrittura sono andate mutando. Qui abbiamo preferito seguire alcune regole generali che sistematizzassero le varie modalità così da consentire una ricerca quanto più agevole possibile. Dunque gli Indici riportano, numero per numero, anno per anno (in base alla numerazione progressiva che talvolta travalica l’anno solare), il titolo dell’articolo pubblicato seguito dal nome dell’autore. Ove possibile, il nome e cognome dell’autore è stato sempre esplicitato (anche quando non lo era nell’Indice originario) al fine di attribuire chiaramente la paternità dell’articolo (per gli pseudonimi, si veda la lista non esaustiva a fine Indici). Si è inoltre evitato di utilizzare le sigle per autori con iniziali simili (per esempio: Luigi Fabbri, Luce Fabbri), tranne che in alcune rubriche (anche per questo si veda la lista delle sigle principali a fine Indici). Sempre con l’obiettivo di facilitare la ricerca, i nomi degli autori stranieri sono stati scritti in lingua originale (per esempio: Pëtr Kropotkin e non Pietro Kropotkin o Kropotkine) e sono stati inoltre corretti alcuni errori presenti nel testo originale (per esempio: non Emile Armand, come era comunemente, ma erroneamente, noto in Italia, bensì E. Armand, effettivo pseudonimo di Ernest Juin). Infine le rubriche sono state evidenziate con il maiuscoletto – LETTERE DEI LETTORI; ANTOLOGIA; RECENSIONI;