Jamaica Plain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nearly Forty Years Ago, a Proposed but Ultimately Defeated Highway Project

A Jackson Square Timeline Late 1800s-1950s: Jackson Square is an important factory and brewing center with thousands of residents employed at the Plant Shoe Factory on Centre and Walden Streets, Chelmsford Ginger Ale Company on Heath Street, Moxie Bottling Company on Bickford Street and four other breweries or bottling plants within a few minutes‘ walk. The Boston and Providence Railroad had a Heath Street station and trolleys operated on Columbus Avenue and Centre Street. See JP Historical Society. Approximately 14,000 people lived in the three census tracts comprising Jackson Square, roughly 35% more than today. 1948: Mass. Dept. of Public Works calls for the construction of multiple highways to go through and around Boston. The proposal includes I-93 and I-90 (both of which were eventually built), as well as an ―Inner Belt‖ (looping from Charlestown through Somerville, Cambridge, Brookline, Roxbury and the South End) and the ―Southwest Expressway‖ (to connect the Inner Belt and I- 95, from Roxbury to Dedham). 1962: The proposed Southwest Expressway, originally aligned with Blue Hill Avenue, is realigned parallel to the Penn Central Railroad through Jamaica Plain, Roslindale and Hyde Park. The highway will be eight lanes wide. 1965: Community and church leaders in Jamaica Plain found ESAC to promote positive social change in the neighborhood. ESAC members are leaders in organizing against the highway. 1966: A ‗Beat the Belt‘ Rally brings together highway opponents from Cambridge, Roxbury, Chinatown, Jamaica Plain, Hyde Park and suburbs including Canton and Dedham and Canton. 1967: Jamaica Plain-based highway opponents hold one of their first meetings at a home on Germania Street, near the abandoned Haffenreffer Brewery (now the JPNDC‘s Brewery Small Business Complex). -

Tax Exempt Property in Boston Analysis of Types, Uses, and Issues

Tax Exempt Property in Boston Analysis of Types, Uses, and Issues THOMAS M. MENINO, MAYOR CITY OF BOSTON Boston Redevelopment Authority Mark Maloney, Director Clarence J. Jones, Chairman Consuelo Gonzales Thornell, Treasurer Joseph W. Nigro, Jr., Co-Vice Chairman Michael Taylor, Co-Vice Chairman Christopher J. Supple, Member Harry R. Collings, Secretary Report prepared by Yolanda Perez John Avault Jim Vrabel Policy Development and Research Robert W. Consalvo, Director Report #562 December 2002 1 Introduction .....................................................................................................................3 Ownership........................................................................................................................3 Figure 1: Boston Property Ownership........................................................................4 Table 1: Exempt Property Owners .............................................................................4 Exempt Land Uses.........................................................................................................4 Figure 2: Boston Exempt Land Uses .........................................................................4 Table 2: Exempt Land Uses........................................................................................6 Exempt Land by Neighborhood .................................................................................6 Table 3: Exempt Land By Neighborhood ..................................................................6 Table 4: Tax-exempt -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Partners Recommendations to DCR

Charles River Conservancy Arborway Coalition June 21, 2021 Bike to the Sea Blackstone River Watershed Association Secretary Kathleen Theoharides Boston Cyclists Union c/o Faye Boardman, Chief Operating Officer & Commission Chair Boston Harbor Now Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900 Boston, MA 02144 Cambridge Bicycle Safety Charles River Watershed Association SENT VIA EMAIL Connecticut River Conservancy Emerald Necklace Conservancy Secretary Theoharides, Esplanade Association Friends of Herter Park Thank you for your continued attention to improving the management, operations and asset condition of the natural, cultural and recreational Friends of Nantasket Beach resources held by the Department of Conservation and Recreation through the Friends of the Blue Hills DCR Special Commission. The work of DCR and this Commission is increasingly Friends of the Boston Harbor Islands urgent as we endeavor to mitigate the effects of climate change, reckon with Friends of the Malden River inequity, invest in environmental justice communities, and recover from the Friends of the Middlesex Fells Reservation COVID-19 pandemic. Friends of the Mount Holyoke Range We write once again as a coalition of DCR’s partner organizations from across Friends of Walden Pond the Commonwealth representing dozens of communities, broad expertise in Friends of Wollaston Beach resource management and community engagement, thousands of volunteers, Green Cambridge and millions of dollars leveraged annually to support our state parks. We are Green Streets Initiative grateful for the attention you gave to the April 26th letter, and the fulfillment of several requests to make the Commission process more robust and accessible Lawrence & Lillian Solomon Foundation for public input, including meeting the legislative mandate to fill the second LivableStreets Alliance Commission seat for a representative of friends groups, a modest timeline Magazine Beach Partners extension, and holding additional stakeholder engagement sessions. -

Heart of the City Final Report

THE HEART OF THE CITY BY ASHLEY G. LANFER WORKING PAPER 9 November 22, 2003 RAPPAPORT INSTITUTE FOR GREATER BOSTON JOHN F. KENNEDY SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT HARVARD UNIVERSITY RAPPAPORT INSTITUTE FOR GREATER BOSTON …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………….. PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the past generation, the City of Boston been part of an historic urban renaissance in the United States. After years of serious decline, when businesses and population fled the city as racial and social problems festered, Boston has used its strategic location, priceless institutional assets, and grassroots know-how to offer a vital place to live, work, and enjoy cultural and community life. At a time when government is denigrated in the political discourse, Boston City Hall has developed programs and policies that have won acclaim for their pragmatism and effectiveness — including community policing, Main Streets business districts, nonprofit housing development, public-private partnerships in hospitals and community health centers, building-level reform of public schools, a small but significant growth in school choice, devel- opment of whole new neighborhoods and transit systems, and a renewal of citywide park sys- tems. These programs and strategies work because they create place-specific approaches to problems, where people are engaged in fixing their own communities and institutions. Mayor Thomas M. Menino, Police Commissioner Paul Evans, Schools Superintendent Thomas Pay- zant, the late Parks Commissioner Justine Liff, and others have provided very real leadership from City Hall — as have community leaders in all neighborhoods and even field of endeavor. One of the areas to experience the most striking renaissance is the area that we call the Heart of the City. -

Southwest Corridor Park Voted 'Best of Boston' 2020

PAGE 1 THE BOSTON SUN If you are looking to get in contactAU withGUST our 6, staff 2020 STUDENTS HEAD BACK TO SCHOOL GREETED WITH or any info related to the Boston Sun please call 781-485-0588 or contact us via email. A 5-STAR SURPRISE . READ ABOUT IT ON PAGE 10 Email addresses are listed on the editorial page. THURSDAY, AUGUST 6, 2020 PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY SERVING BACK BAY - SOUTH END - FENWAY - KENMORE Southwest Corridor Park voted ‘Best of Boston’ 2020 By Lauren Bennett and organizations goes into keep- ing the park beautiful and enjoy- The Southwest Corridor Park, able for all. known by many as a peaceful It’s a real team effort and many escape running through the center hands go into helping out with of bustling Boston from Jamaica the different sections of the park, Plan and Roxbury to the South but the Sun spoke with Fran- End and Back Bay, was recently co Campanello, President of the chosen as the “Best Secret Gar- Southwest Corridor Park Conser- den” by Boston Magazine in its vancy (SWCP), as well as Jenni- 2020 Best of Boston issue. fer Leonard, Chair of the South- The magazine admits the park west Corridor Park Management “isn’t exactly a secret,” as it is used Advisory Council (PMAC). The by many to commute, play, or just SWPC looks after the portion of enjoy some fresh air. However, a lot of hard work from volunteers PHOTOS BY SETH DANIEL (SOUTHWEST CORRIDOR, Pg. 7) HIDDEN GARDEN…The Southwest Corridor Park in the South End and Back Bay was named Best Secret Garden by Boston Magazine’s Best of Boston in the most recent issue. -

Report on the Real Property Owned and Leased by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office for Administration and Finance Report on the Real Property Owned and Leased by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Published February 15, 2019 Prepared by the Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance Carol W. Gladstone, Commissioner This page was intentionally left blank. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Report Organization 5 Table 1 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Executive Office 11 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 2 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by County 17 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 3 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Executive Office and Agency 23 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 4 Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Site and Municipality 85 Total land acreage, buildings (number and square footage), improvements (number and area) Includes State and Authority-owned buildings Table 5 Commonwealth Active Lease Agreements by Municipality 303 Private leases through DCAMM on behalf of state agencies APPENDICES Appendix I Summary of Commonwealth-Owned Real Property by Executive Office 311 Version of Table 1 above but for State-owned only (excludes Authorities) Appendix II County-Owned Buildings Occupied by Sheriffs and the Trial Court 319 Appendix III List of Conservation/Agricultural/Easements Held by the Commonwealth 323 Appendix IV Data Sources 381 Appendix V Glossary of Terms 385 Appendix VI Municipality Associated Counties Index Key 393 3 This page was intentionally left blank. -

Southwest Corridor Park 2015 Highlights

Parkland Management Advisory Committee (PMAC) Southwest Corridor Park 2015 Highlights About PMAC 100 inches of snow did not keep people indoors, and DCR staff worked tirelessly to make the SWC For over two decades, the Parkland Park one of the best travel routes in the city. Management Advisory Committee (PMAC) has provided a forum for community voice for the Southwest Corridor Park. Through PMAC and 600 responses came in to PMAC’s online survey the Southwest Corridor Park Conservancy on bicycle-pedestrian path issues. This strong (SWCPC) and others, the energy of park users response demonstrates the importance of the and volunteers makes the Southwest Corridor Southwest Corridor Park to the many people who Park one of the most intensely-used and most- use it for walking, jogging, appreciated urban parks in the state parks bicycling and more. network. Web: http://swcpc.org/pmac.htm Our bicycle-pedestrian path ad hoc committee looked at strategies for promoting Have you seen? safety and a culture of courtesy and civility on the SWC path, and is working New LED lighting – thank you to DCR! with DCR and City of Boston officials on next steps. New signs marking the entrances to the eleven community gardens designed by community 1,500 hours of volunteers and provided gardening and by DCR. landscaping in the park through the A new raised bed herb garden, Southwest Corridor developed by community Park Conservancy partner Herbstalk, provides (SWCPC). These a new focal point along the park. hours reflect the work of volunteers on The Mary Snyder Haggerty eighteen volunteer Memorial Bench and Tree provides a days plus over 800 remembrance for one of the planners who hours from neighbors working on their own and in worked on early park design and provides small groups throughout the week. -

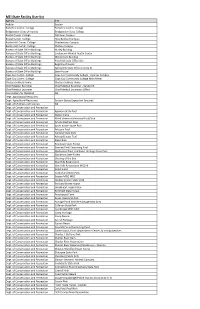

MEI State Facilities Inventory List.Xlsx

MEI State Facility User list Agency Site Auditor Boston Berkshire Comm. College Berkshire Comm. College Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State College Bristol Comm. College Fall River Campus Bristol Comm. College New Bedford Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Charlestown Campus Bunker Hill Comm. College Chelsea Campus Bureau of State Office Buildings Hurley Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Lindemann Mental Health Center Bureau of State Office Buildings McCormack Building Bureau of State Office Buildings Pittsfield State Office Site Bureau of State Office Buildings Registry of Deeds Bureau of State Office Buildings Springfield State Office Liberty St Bureau of State Office Buildings State House Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College ‐ Hyannis Campus Cape Cod Comm. College Cape Cod Community College Main Meter Chelsea Soldiers Home Chelsea Soldiers Home Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiner ‐ Sandwich Chief Medical Examiner Chief Medical Examiners Office Commission for the Blind NA Dept. Agricultural Resources Dept. Agricultural Resources Eastern States Exposition Grounds Dept. of Children and Families NA Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Agawam State Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Aleixo Arena Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Allied Veterans Memorial Pool/Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Amelia Eairhart Dam Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ames Nowell State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Artesani Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashland State Park Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Ashuwillticook Trail Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bajko Rink Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Beartown State Forest Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Bennett Field Swimming Pool Dept. of Conservation and Recreation Blackstone River and Canal Heritage State Park Dept. -

Ocm30840849-5.Pdf (2.204Mb)

XT y. rf lJ:r-, Metropolitan District Commission)nj FACILITY GUIDE A " Metropolitan Parks Centennial • 1893-1993 "Preserving the past.,, protecting the future. The Metropolitan District Commission is a unique multi-service agency with broad responsibihties for the preservation, main- tenance and enhancement of the natural, scenic, historic and aesthetic qualities of the environment within the thirty-four cit- ies and towns of metropolitan Boston. As city and town boundaries follow the middle of a river or bisect an important woodland, a metropolitan organization that can manage the entire natural resource as a single entity is essential to its protec- tion. Since 1893, the Metropolitan District Com- mission has preserved the region's unique resources and landscape character by ac- quiring and protecting park lands, river corridors and coastal areas; reclaiming and restoring abused and neglected sites and setting aside areas of great scenic beauty as reservations for the refreshment, recrea- tion and health of the region's residents. This open space is connected by a network Charles Eliot, the principle of landscaped parkways and bridges that force behind today's MDC. are extensions of the parks themselves. The Commission is also responsible for a scape for the enjoyment of its intrinsic val- vast watershed and reservoir system, ues; providing programs for visitors to 120,000 acres of land and water resources, these properties to encourage appreciation that provides pure water from pristine and involvment with their responsible use, areas to 2.5 million people. These water- providing facilities for active recreation, shed lands are home to many rare and en- healthful exercise, and individual and dangered species and comprise the only team athletics; protecting and managing extensive wilderness areas of Massachu- both public and private watershed lands in setts. -

06 Management

A landscape park requires, more than most works of men, continuity of management. Its perfection is a slow process. Its directors must thoroughly Standard maintenance apprehend the fact that the beauty of its landscape is all that justifies the includes cutting grass, picking existence of a large public space in the midst, or even on the immediate up litter three times a week in borders, of a town. As trustees of park scenery, they will be especially watchful to prevent injury thereto from the intrusion of incongruous or obtrusive the summer (daily when nec- structures, statues, gardens (whether floral, botanic, or zoologic), speedways, essary), repairing potholes, or any other instruments of special modes of recreation, however desirable such sweeping parkways, and emp- may be in their proper place. tying trash barrels. A separate CHARLES WILLIAM ELIOT, CHARLES ELIOT, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, crew prunes and removes dead and hazardous trees. The or the Charles River Basin to continue as Boston’s Central Park, MDC Engineering and substantial investments of time, funds, and staff will be required Construction Division con- over the next fifteen years. When the master plan for New York’s tracts out work for larger park Central Park was completed in , a partnership between the city projects, such as bridges and parkland restoration. MAINTAINING THE SHORE LINE IS ONE OF and the Central Park Conservancy spent millions of dollars over THE MOST CHALLENGING MAINTENANCE TASKS IN THE BASIN. (MDC photo) ten years to restore this neglected resource. Crews trained in park Existing Conditions and Issues restoration were added to existing maintenance crews, dramatically A detailed study of maintenance operations, budgets, and staffing was improving care. -

Metropolitan District Commission Reservations and Facilities Guide

s 2- / (Vjjh?- e^qo* • M 5 7 UMASS/AMHERST A 31E0bt,01t3b0731b * Metropolitan District Commission Reservations and Facilities Guide MetroParks MetroParkways MetroPoRce PureWater 6 Table of Contents OPEN SPACE - RESERVATIONS Beaver Brook Reservation 2 Belle Isle Marsh Reservation 3 Blue Hills Reservation 4 Quincy Quarries Historic Site 5 Boston Harbor Islands State Park 6-7 Breakheart Reservation 8 Castle Island 9 Charles River Reservation 9-11 Lynn/Nahant Beach Reservation 12 Middlesex Fells Reservation 13 Quabbin Reservoir 14 Southwest Corridor Park 15 S tony Brook Reserv ation 1 Wollaston Beach Reservation 17 MAP 18-19 RECREATIONAL FACILITIES Bandstands and Music Shells 21 Beaches 22 Bicycle Paths 23 Boat Landings/Boat Launchings 23 Camping 24 Canoe Launchings 24 Canoe Rentals 24 Fishing 25 Foot Trails and Bridle Paths 26 Golf Courses 26 Museums and Historic Sites 27 Observation Towers 27 Pedestrian Parks 28 Running Paths 28 Sailing Centers 28 Skiing Trails 29 Skating Rinks 30-31 Swimming Pools 32-33 Tennis Courts 34 Thompson Ctr. for the Handicapped 35 Zoos 35 Permit Information 36 GENERAL INFORMATION 37 Metropolitan District Commission Public Information Office 20 Somerset Street, Boston, MA 02108 (617) 727-5215 Open Space... Green rolling hills, cool flowing rivers, swaying trees, crisp clean air. This is what we imagine when we think of open space. The Metropolitan District Commission has been committed to this idea for over one hundred years. We invite you to enjoy the many open spaces we are offering in the metropolitan Boston area. Skiing in the Middlesex Fells Reservation, sailing the Charles River, or hiking at the Blue Hills are just a few of the activities offered.