Heart of the City Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAPC TOD Report.Indd

Growing Station Areas The Variety and Potential of Transit Oriented Development in Metro Boston June, 2012 Table of Contents Executive Summary Introduction Context for TOD in Metro Boston A Transit Station Area Typology for Metro Boston Estimating the Potential for TOD Conclusions Matrix of Station Area Types and TOD Potential Station Area Type Summaries Authors: Tim Reardon, Meghna Dutta MAPC contributors: Jennifer Raitt, Jennifer Riley, Christine Madore, Barry Fradkin Advisor: Stephanie Pollack, Dukakis Center for Urban & Regional Policy at Northeastern University Graphic design: Jason Fairchild, The Truesdale Group Funded by the Metro Boston Consortium for Sustainable Communities and the Boston Metropolitan Planning Organization with support from the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University. Thanks to the Metro Boston Transit Oriented Development Finance Advi- sory Committee for their participation in this effort. Visit www.mapc.org/TOD to download this report, access the data for each station, or use our interactive map of station areas. Cover Photos (L to R): Waverly Woods, Hamilton Canal Lofts, Station Landing, Bartlett Square Condos, Atlantic Wharf. Photo Credits: Cover (L to R): Ed Wonsek, DBVW Architects, 75 Station Landing, Maple Hurst Builders, Anton Grassl/Esto Inside (Top to Bottom): Pg1: David Steger, MAPC, SouthField; Pg 3: ©www.bruceTmartin.com, Anton Grassl/Esto; Pg 8: MAPC; Pg 14: Boston Redevel- opment Authority; Pg 19: ©www.bruceTmartin.com; Pg 22: Payton Chung flickr, David Steger; Pg -

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

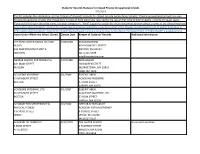

y NOTE WONOERLAND 7 THERE HOLDERS Of PREPAID PASSES. ON DECEMBER , 1977 WERE 22,404 2903 THIS AMOUNTS TO AN ESTIMATED (44 ,608 ) PASSENGERS PER DAY, NOT INCLUDED IN TOTALS BELOW REVERE BEACH I OAK 8R0VC 1266 1316 MALOEN CENTER BEACHMONT 2549 1569 SUFFOLK DOWNS 1142 ORIENT< NTS 3450 WELLINGTON 5122 WOOO ISLANC PARK 1071 AIRPORT SULLIVAN SQUARE 1397 6668 I MAVERICK LCOMMUNITY college 5062 LECHMERE| 2049 5645 L.NORTH STATION 22,205 6690 HARVARD HAYMARKET 6925 BOWDOIN , AQUARIUM 5288 1896 I 123 KENDALL GOV CTR 1 8882 CENTRAL™ CHARLES^ STATE 12503 9170 4828 park 2 2 766 i WASHINGTON 24629 BOYLSTON SOUTH STATION UNDER 4 559 (ESSEX 8869 ARLINGTON 5034 10339 "COPLEY BOSTON COLLEGE KENMORE 12102 6102 12933 WATER TOWN BEACON ST. 9225' BROADWAY HIGHLAND AUDITORIUM [PRUDENTIAL BRANCH I5I3C 1868 (DOVER 4169 6063 2976 SYMPHONY NORTHEASTERN 1211 HUNTINGTON AVE. 13000 'NORTHAMPTON 3830 duole . 'STREET (ANDREW 6267 3809 MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY ricumt inoicati COLUMBIA APFKOIIUATC 4986 ONE WAY TRAFFIC 40KITT10 AT RAPID TRANSIT LINES STATIONS (EGLESTON SAVIN HILL 15 98 AMD AT 3610 SUBWAY ENTRANCES DECEMBER 7,1977 [GREEN 1657 FIELDS CORNER 4032 SHAWMUT 1448 FOREST HILLS ASHMONT NORTH OUINCY I I I 99 8948 3930 WOLLASTON 2761 7935 QUINCY CENTER M b 6433 It ANNUAL REPORT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/annualreportmass1978mass BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1978 ROBERT R. KILEY Chairman and Chief Executive Officer RICHARD D. BUCK GUIDO R. PERERA, JR. "V CLAIRE R. BARRETT THEODORE C. LANDSMARK NEW MEMBERS OF THE BOARD — 1979 ROBERT L. FOSTER PAUL E. MEANS Chairman and Chief Executive Officer March 20, 1979 - January 29. -

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2

Students' Records Statuses for Closed Private Occupational Schools 7/2/2019 This list includes the information on the statuses of students' records for closed, private occupational schools. Private occupational schools are non- Private occupational schools that closed prior to August 2012 were only required by the law at that time to hold students' records for seven years; If you don't find your school by name, use your computer's "Find" feature to search the entire document by your school's name as the school may have Information about students' records for closed degree-granting institutions may be located at the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education is Information about students' records for closed hospital-based nursing programs may be located at the Department of Public Health is available here. Name Under Which the School Closed Closure Date Keeper of Students' Records Additional Information 7TH ROW CENTER HANDS-ON! CAR 7/28/2008 KEVAN BUDROW AUDIO 60 BLOOMFIELD STREET 325 NEW BOSTON ST UNIT 6 BOSTON, MA 02124 WOBURN (617) 265-6939 [email protected] ABARAE SCHOOL FOR MODELING 4/20/1990 DIDA HAGAN 442 MAIN STREET 18 WARREN STREET MALDEN GEORGETOWN, MA 01833 (508) 352-7200 ACADEMIE MODERNE 4/1/1989 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. 4/1/1987 EILEEN T ABEN 45 NEWBURY STREET ACADEMIE MODERNE, LTD. BOSTON 57 BOW STREET CARVER, MA 02339 ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY & 6/9/1989 ARTHUR SCHMALBACH PHYSICAL FITNESS ACADEMY FOR MYOTHERAPY 9 SCHOOL STREET 9 SCHOOL STREET LENOX LENOX, MA 01240 (413) 637-0317 ACADEMY OF LEARNING 9/30/2003 THE SALTER SCHOOL No records available. -

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease

Downtown Crossing 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA 02108 Space for Lease DESCRIPTION n 8,131 SF available for lease n Located across from Boston’s 24,000 SF Walgreens, within blocks of Millennium Tower, the Paramount Theater, Boston Opera House n Three-story (plus basement) building located and the Omni Parker House Hotel on School Street near the intersection of Washington Street on the Freedom Trail in Boston’s Downtown Crossing retail corridor n Area retailers: Roche Bobois, Loews Theatre, Macy’s, Staples, Eddie Bauer Outlet, Gap Outlet; The Merchant, Salvatore’s, Teatro, GEM, n Exceptional opportunity for new flagship location Papagayo, MAST’, Latitude 360, Pret A Manger restaurants; Boston Common Coffee Co. and Barry’s Bootcamp n Two blocks from three MBTA stations - Park Street, Downtown Crossing and State Street FOR MORE INFORMATION Jenny Hart, [email protected], 617.369.5910 Lindsey Sandell, [email protected], 617.369.5936 351 Newbury Street | Boston, MA 02115 | F 617.262.1806 www.dartco.com 19-21 School Street, Boston, MA Cambridge East Boston INTERSTATE 49593 North End 1 N Beacon Hill Charles River SITE Financial W E District Boston Common INTERSTATE S 49593 INTERSTATE 49590 Seaport District INTERSTATE Chinatown 49590 1 SITE DATA n Located in the Downtown Crossing Washington Street Shopping District n 35 million SF of office space within the Downtown Crossing District n Office population within 1/2 mile: 190,555 n 2 blocks from the Financial District with approximately 50 million SF of office space DEMOGRAPHICS Residential Average -

MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-8 OMB No. 1024-0018 MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Mount Auburn Cemetery Other Name/Site Number: n/a 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Roughly bounded by Mount Auburn Street, Not for publication:_ Coolidge Avenue, Grove Street, the Sand Banks Cemetery, and Cottage Street City/Town: Watertown and Cambridge Vicinityj_ State: Massachusetts Code: MA County: Middlesex Code: 017 Zip Code: 02472 and 02318 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object:_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 4 buildings 1 ___ sites 4 structures 15 ___ objects 26 8 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 26 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MOUNT AUBURN CEMETERY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Nearly Forty Years Ago, a Proposed but Ultimately Defeated Highway Project

A Jackson Square Timeline Late 1800s-1950s: Jackson Square is an important factory and brewing center with thousands of residents employed at the Plant Shoe Factory on Centre and Walden Streets, Chelmsford Ginger Ale Company on Heath Street, Moxie Bottling Company on Bickford Street and four other breweries or bottling plants within a few minutes‘ walk. The Boston and Providence Railroad had a Heath Street station and trolleys operated on Columbus Avenue and Centre Street. See JP Historical Society. Approximately 14,000 people lived in the three census tracts comprising Jackson Square, roughly 35% more than today. 1948: Mass. Dept. of Public Works calls for the construction of multiple highways to go through and around Boston. The proposal includes I-93 and I-90 (both of which were eventually built), as well as an ―Inner Belt‖ (looping from Charlestown through Somerville, Cambridge, Brookline, Roxbury and the South End) and the ―Southwest Expressway‖ (to connect the Inner Belt and I- 95, from Roxbury to Dedham). 1962: The proposed Southwest Expressway, originally aligned with Blue Hill Avenue, is realigned parallel to the Penn Central Railroad through Jamaica Plain, Roslindale and Hyde Park. The highway will be eight lanes wide. 1965: Community and church leaders in Jamaica Plain found ESAC to promote positive social change in the neighborhood. ESAC members are leaders in organizing against the highway. 1966: A ‗Beat the Belt‘ Rally brings together highway opponents from Cambridge, Roxbury, Chinatown, Jamaica Plain, Hyde Park and suburbs including Canton and Dedham and Canton. 1967: Jamaica Plain-based highway opponents hold one of their first meetings at a home on Germania Street, near the abandoned Haffenreffer Brewery (now the JPNDC‘s Brewery Small Business Complex). -

Tax Exempt Property in Boston Analysis of Types, Uses, and Issues

Tax Exempt Property in Boston Analysis of Types, Uses, and Issues THOMAS M. MENINO, MAYOR CITY OF BOSTON Boston Redevelopment Authority Mark Maloney, Director Clarence J. Jones, Chairman Consuelo Gonzales Thornell, Treasurer Joseph W. Nigro, Jr., Co-Vice Chairman Michael Taylor, Co-Vice Chairman Christopher J. Supple, Member Harry R. Collings, Secretary Report prepared by Yolanda Perez John Avault Jim Vrabel Policy Development and Research Robert W. Consalvo, Director Report #562 December 2002 1 Introduction .....................................................................................................................3 Ownership........................................................................................................................3 Figure 1: Boston Property Ownership........................................................................4 Table 1: Exempt Property Owners .............................................................................4 Exempt Land Uses.........................................................................................................4 Figure 2: Boston Exempt Land Uses .........................................................................4 Table 2: Exempt Land Uses........................................................................................6 Exempt Land by Neighborhood .................................................................................6 Table 3: Exempt Land By Neighborhood ..................................................................6 Table 4: Tax-exempt -

Massachusetts Schools of Cosmetology, Barbering and Electrology Private & Vocational Schools

MASSACHUSETTS SCHOOLS OF COSMETOLOGY, BARBERING AND ELECTROLOGY PRIVATE & VOCATIONAL SCHOOLS COSMETOLOGY Blackstone Valley Regional Voc Tech School-Cosmetology Dept Aesthetic Institute of Boston Cosmetology Program 47 Spring Street 65 Pleasant Street West Roxbury, MA 02132 Upton, MA 01568 617-327-4550 508-529-7758 Alexander Academy Inc. Blessing Channels Nail Academy Cosmetology and Barbering Program Manicuring Program 112 River Street 76 Winn St #1C Fitchburg, MA 01420 Woburn, MA 01801 978-345-0011 781-729-8868 Aliano School of Cosmetology, Inc. Blue Hills Regional Tech Sch. Cosmetology Program Cosmetology/Aesthetic Program 541 West Street 800 Randolph Street PO Box 4740 Canton, MA 02021 Brockton, MA 02303 781-828-5800 508-583-5433 BMC Durfee High School Ali May Aesthetic Academy Cosmetology Program Aesthetic Program 360 Elsbree Street 1459 Hancock St Fall River, MA 02720 Quincy, MA 02169 508-675-8100 617-438-2753 Bojack Academy of Beauty Culture Ali May Aesthetic Academy Cosmetology/Aesthetic Programs Manicuring Program 47 Spring Street 1459 Hancock St W. Roxbury, MA 02132 Quincy, MA 02169 617-323-0844 617-438-2753 Bristol-Plymouth Reg Tech Sch. Assabet Valley Regional HS Cosmetology Program Cosmetology/Aesthetic Program 940 County Street, Route 140 215 Fitchburg Street Taunton, MA 02780 Marlboro, MA 01752 508-823-5151 508-485-9430 x 1447 C.H. McCann Tech. High School Bay Path Voc. Tech HS Cosmetology Program Cosmetology Program Hodges Cross Road 57 Old Mugget Hill Road North Adams, MA 01247 Charlton, MA 01507 413-663-8424 508-248-5971 1 of 8 (rev. 4/19/2016) MASSACHUSETTS SCHOOLS OF COSMETOLOGY, BARBERING AND ELECTROLOGY PRIVATE & VOCATIONAL SCHOOLS Cali for Nails Academy Digrigoli School of Cosmetology Manicuring Program Cosmetology Program 204 Adams Street 1578 Riverdale Street Dorchester, MA 02122 W. -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities. -

Boston a Guide Book to the City and Vicinity

1928 Tufts College Library GIFT OF ALUMNI BOSTON A GUIDE BOOK TO THE CITY AND VICINITY BY EDWIN M. BACON REVISED BY LeROY PHILLIPS GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON ATLANTA • DALLAS • COLUMBUS • SAN FRANCISCO COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY GINN AND COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 328.1 (Cfte gtftengum ^regg GINN AND COMPANY • PRO- PRIETORS . BOSTON • U.S.A. CONTENTS PAGE PAGE Introductory vii Brookline, Newton, and The Way about Town ... vii Wellesley 122 Watertown and Waltham . "123 1. Modern Boston i Milton, the Blue Hills, Historical Sketch i Quincy, and Dedham . 124 Boston Proper 2 Winthrop and Revere . 127 1. The Central District . 4 Chelsea and Everett ... 127 2. The North End .... 57 Somerville, Medford, and 3. The Charlestown District 68 Winchester 128 4. The West End 71 5. The Back Bay District . 78 III. Public Parks 130 6. The Park Square District Metropolitan System . 130 and the South End . loi Boston City System ... 132 7. The Outlying Districts . 103 IV. Day Trips from Boston . 134 East Boston 103 Lexington and Concord . 134 South Boston .... 103 Boston Harbor and Massa- Roxbury District ... 105 chusetts Bay 139 West Roxbury District 105 The North Shore 141 Dorchester District . 107 The South Shore 143 Brighton District. 107 Park District . Hyde 107 Motor Sight-Seeing Trips . 146 n. The Metropolitan Region 108 Important Points of Interest 147 Cambridge and Harvard . 108 Index 153 MAPS PAGE PAGE Back Bay District, Showing Copley Square and Vicinity . 86 Connections with Down-Town Cambridge in the Vicinity of Boston vii Harvard University ... -

Maximizing the Benefits of Mass Transit Services

Maximizing the Benefits of Mass Transit Stations: Amenities, Services, and the Improvement of Urban Space within Stations by Carlos Javier Montafiez B.A. Political Science Yale University, 1997 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2004 Q Carlos Javier Montafiez. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: / 'N Dep tment of Urban Studies and Plav ning Jvtay/, 2004 Certified by: J. Mai Schuster, PhD Pfessor of U ban Cultural Policy '09 Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: / Dennis Frenthmfan, MArchAS, MCP Professor of the Practice of Urban Design Chair, Master in City Planning Committee MASSACH USEUSq INSTIUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 21 2004 ROTCH LIBRARIES Maximizing the Benefits of Mass Transit Stations: Amenities, Services, and the Improvement of Urban Space within Stations by Carlos Javier Montafiez B.A. Political Science Yale University, 1997 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 20, 2004 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning ABSTRACT Little attention has been paid to the quality of the spaces within rapid mass transit stations in the United States, and their importance as places in and of themselves. For many city dwellers who rely on rapid transit service as their primary mode of travel, descending and ascending into and from transit stations is an integral part of daily life and their urban experience. -

UVRA GPS Field/Gym Locations & Directions

UVRA GPS Field/Gym Locations & Directions CCBA Witherell Center – 1 Campbell Street, Lebanon NH 03766 From the North: I-89 south to Exit 18 (DHMC/Lebanon High School). Bear right off the exit and continue on Route 120 to stop sign. Turn left onto Hanover St. Follow Hanover St. for approximately 1/2 mile and take a left into the parking lot next to Village Pizza/Peking Tokyo/Lebanon Floral mini-mall. Stay to the left and go down a slight hill bearing to the right at the bottom of the hill. Continue around the municipal parking lot onto Taylor St. The Witherell Center will be on you left. From the South: I-89 to Exit 17 (Enfield/Lebanon).Take a left off the exit and follow Route 4 into downtown Lebanon. Approx. 3 miles. At the green take your first right onto Campbell St. Turn right at the end of Campbell St. onto Parkhurst St. Take your first left onto Spencer St., go approx. 100 yards and drive straight into the Witherell Center's parking lot. CLAREMONT From I-91 south or north: to Exit #8, route 103 to the center of Claremont. At the rotary/parking in center of town, take the third right (city hall on the left). You are now on Broad Street. Broad Street Park (gazebo in center) is on your left. Now follow the directions to the place you are playing at: Monadnock Park – Broad Street, Claremont NH 03743 Go ¼ mile down Broad Street. Stevens High School is on the right. After passing Stevens High take your first left which is the access road leading down into Monadnock Park.