PLINY, TRAJAN, HADRIAN and the CHRISTIANS* in the Seventh Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Domitian's Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome

Rising from the Ashes: Domitian’s Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome Lea K. Cline In the August 1888 edition of the Notizie degli Scavi, profes- on a base of two steps; it is a long, solid rectangle, 6.25 m sors Guliermo Gatti and Rodolfo Lanciani announced the deep, 3.25 m wide, and 1.26 m high (lacking its crown). rediscovery of a Domitianic altar on the Quirinal hill during These dimensions make it the second largest public altar to the construction of the Casa Reale (Figures 1 and 2).1 This survive in the ancient capital. Built of travertine and revet- altar, found in situ on the southeast side of the Alta Semita ted in marble, this altar lacks sculptural decoration. Only its (an important northern thoroughfare) adjacent to the church inscription identifies it as an Ara Incendii Neroniani, an altar of San Andrea al Quirinale, was not unknown to scholars.2 erected in fulfillment of a vow made after the great fire of The site was discovered, but not excavated, in 1644 when Nero (A.D. 64).7 Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini) and Gianlorenzo Bernini Archaeological evidence attests to two other altars, laid the foundations of San Andrea al Quirinale; at that time, bearing identical inscriptions, excavated in the sixteenth the inscription was removed to the Vatican, and then the and seventeenth centuries; the Ara Incendii Neroniani found altar was essentially forgotten.3 Lanciani’s notes from May on the Quirinal was the last of the three to be discovered.8 22, 1889, describe a fairly intact structure—a travertine block Little is known of the two other altars; one, presumably altar with remnants of a marble base molding on two sides.4 found on the Vatican plain, was reportedly used as building Although the altar’s inscription was not in situ, Lanciani refers material for the basilica of St. -

The Gallic Empire (260-274): Rome Breaks Apart

The Gallic Empire (260-274): Rome Breaks Apart Six Silver Coins Collection An empire fractures Roman chariots All coins in each set are protected in an archival capsule and beautifully displayed in a mahogany-like box. The box set is accompanied with a story card, certificate of authenticity, and a black gift box. By the middle of the third century, the Roman Empire began to show signs of collapse. A parade of emperors took the throne, mostly from the ranks of the military. Years of civil war and open revolt led to an erosion of territory. In the year 260, in a battle on the Eastern front, the emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by the hated Persians. He died in captivity, and his corpse was stuffed and hung on the wall of the palace of the Persian king. Valerian’s capture threw the already-fractured empire into complete disarray. His son and co-emperor, Gallienus, was unable to quell the unrest. Charismatic generals sought to consolidate their own power, but none was as powerful, or as ambitious, as Postumus. Born in an outpost of the Empire, of common stock, Postumus rose swiftly through the ranks, eventually commanding Roman forces “among the Celts”—a territory that included modern-day France, Belgium, Holland, and England. In the aftermath of Valerian’s abduction in 260, his soldiers proclaimed Postumus emperor. Thus was born the so-called Gallic Empire. After nine years of relative peace and prosperity, Postumus was murdered by his own troops, and the Gallic Empire, which had depended on the force of his personality, began to crumble. -

Let's Review Text Structure!

Grade 6 Day 18 ELA q I Grade 6 Day 18 ELA Grade 6 Day 18 ELA W o Grade 6 Bearcat Day 18 Math pl Grade 6 Bearcat Day 18 Math P2 Grade 6 Bearcat Day 18 Math 173 Grade 6 Bearcat Day 18 Math 104 Grade 6 Day 18 Science pl Grade 6 Day 18 Science P2 Grade 6 Day 18 Science 123 Question for you to turn in. Describe how processes were used to form a landform. Use vocabulary and evidence from the passage to support your answer. RACE. Grade 6 Day 18 Social Studies Grade 6 Day 18 Social Studies to . I ] l n n t t e o o r n n m i i i t r r t t a a p t t h e e a a . r r m h h 1 o o m m t t E r r 0 p p O O e o o n s f f m m r n a i i i l n n o i i r m e e o m p i R t / l m ? ? d d e l l a l l E e e h a a , ci s s T f f s e u u n n n a a m o sp w w o i C C r o o s/ f t t ct t n D D a a e n a s h h s s e i i t m e W W h h n o h r t / co s o t e d r i n n s s p o a i e e e e t i i m s v v n e p r r m m / e i l t e e e e g t c r s s n n a e e o o l E E R R e s. -

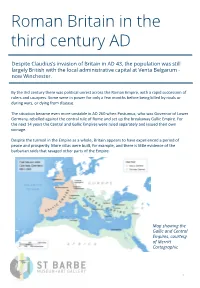

Roman Britain in the Third Century AD

Roman Britain in the third century AD Despite Claudius’s invasion of Britain in AD 43, the population was still largely British with the local administrative capital at Venta Belgarum - now Winchester. By the 3rd century there was political unrest across the Roman Empire, with a rapid succession of rulers and usurpers. Some were in power for only a few months before being killed by rivals or during wars, or dying from disease. The situation became even more unstable in AD 260 when Postumus, who was Governor of Lower Germany, rebelled against the central rule of Rome and set up the breakaway Gallic Empire. For the next 14 years the Central and Gallic Empires were ruled separately and issued their own coinage. Despite the turmoil in the Empire as a whole, Britain appears to have experienced a period of peace and prosperity. More villas were built, for example, and there is little evidence of the barbarian raids that ravaged other parts of the Empire. Map showing the Gallic and Central Empires, courtesy of Merritt Cartographic 1 The Boldre Hoard The Boldre Hoard contains 1,608 coins, dating from AD 249 to 276 and issued by 12 different emperors. The coins are all radiates, so-called because of the radiate crown worn by the emperors they depict. Although silver, the coins contain so little of that metal (sometimes only 1%) that they appear bronze. Many of the coins in the Boldre Hoard are extremely common, but some unusual examples are also present. There are three coins of Marius, for example, which are scarce in Britain as he ruled the Gallic Empire for just 12 weeks in AD 269. -

Collector's Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage

Liberty Coin Service Collector’s Checklist for Roman Imperial Coinage (49 BC - AD 518) The Twelve Caesars - The Julio-Claudians and the Flavians (49 BC - AD 96) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Julius Caesar (49-44 BC) Augustus (31 BC-AD 14) Tiberius (AD 14 - AD 37) Caligula (AD 37 - AD 41) Claudius (AD 41 - AD 54) Tiberius Nero (AD 54 - AD 68) Galba (AD 68 - AD 69) Otho (AD 69) Nero Vitellius (AD 69) Vespasian (AD 69 - AD 79) Otho Titus (AD 79 - AD 81) Domitian (AD 81 - AD 96) The Nerva-Antonine Dynasty (AD 96 - AD 192) Nerva (AD 96-AD 98) Trajan (AD 98-AD 117) Hadrian (AD 117 - AD 138) Antoninus Pius (AD 138 - AD 161) Marcus Aurelius (AD 161 - AD 180) Hadrian Lucius Verus (AD 161 - AD 169) Commodus (AD 177 - AD 192) Marcus Aurelius Years of Transition (AD 193 - AD 195) Pertinax (AD 193) Didius Julianus (AD 193) Pescennius Niger (AD 193) Clodius Albinus (AD 193- AD 195) The Severans (AD 193 - AD 235) Clodius Albinus Septimus Severus (AD 193 - AD 211) Caracalla (AD 198 - AD 217) Purchase Emperor Denomination Grade Date Price Geta (AD 209 - AD 212) Macrinus (AD 217 - AD 218) Diadumedian as Caesar (AD 217 - AD 218) Elagabalus (AD 218 - AD 222) Severus Alexander (AD 222 - AD 235) Severus The Military Emperors (AD 235 - AD 284) Alexander Maximinus (AD 235 - AD 238) Maximus Caesar (AD 235 - AD 238) Balbinus (AD 238) Maximinus Pupienus (AD 238) Gordian I (AD 238) Gordian II (AD 238) Gordian III (AD 238 - AD 244) Philip I (AD 244 - AD 249) Philip II (AD 247 - AD 249) Gordian III Trajan Decius (AD 249 - AD 251) Herennius Etruscus -

The Epitome De Caesaribus and the Thirty Tyrants

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ELTE Digital Institutional Repository (EDIT) THE EPITOME DE CAESARIBUS AND THE THIRTY TYRANTS MÁRK SÓLYOM The Epitome de Caesaribus is a short, summarizing Latin historical work known as a breviarium or epitomé. This brief summary was written in the late 4th or early 5th century and summarizes the history of the Roman Empire from the time of Augustus to the time of Theodosius the Great in 48 chapters. Between chapters 32 and 35, the Epitome tells the story of the Empire under Gallienus, Claudius Gothicus, Quintillus, and Aurelian. This was the most anarchic time of the soldier-emperor era; the imperatores had to face not only the German and Sassanid attacks, but also the economic crisis, the plague and the counter-emperors, as well. The Scriptores Historiae Augustae calls these counter-emperors the “thirty tyrants” and lists 32 usurpers, although there are some fictive imperatores in that list too. The Epitome knows only 9 tyrants, mostly the Gallic and Western usurpers. The goal of my paper is to analyse the Epitome’s chapters about Gallienus’, Claudius Gothicus’ and Aurelian’s counter-emperors with the help of the ancient sources and modern works. The Epitome de Caesaribus is a short, summarizing Latin historical work known as a breviarium or epitomé (ἐπιτομή). During the late Roman Empire, long historical works (for example the books of Livy, Tacitus, Suetonius, Cassius Dio etc.) fell out of favour, as the imperial court preferred to read shorter summaries. Consequently, the genre of abbreviated history became well-recognised.1 The word epitomé comes from the Greek word epitemnein (ἐπιτέμνειν), which means “to cut short”.2 The most famous late antique abbreviated histories are Aurelius Victor’s Liber de Caesaribus (written in the 360s),3 Eutropius’ Breviarium ab Urbe condita4 and Festus’ Breviarium rerum gestarum populi Romani.5 Both Eutropius’ and Festus’ works were created during the reign of Emperor Valens between 364 and 378. -

The Extension of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 285-305Ce

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 The Extension Of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian And The Tetrarchy, 285-305ce Joshua Petitt University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Petitt, Joshua, "The Extension Of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian And The Tetrarchy, 285-305ce" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2412. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2412 THE EXTENSION OF IMPERIAL AUTHORITY UNDER DIOCLETIAN AND THE TETRARCHY, 285-305CE. by JOSHUA EDWARD PETITT B.A. History, University of Central Florida 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 © 2012 Joshua Petitt ii ABSTRACT Despite a vast amount of research on Late Antiquity, little attention has been paid to certain figures that prove to be influential during this time. The focus of historians on Constantine I, the first Roman Emperor to allegedly convert to Christianity, has often come at the cost of ignoring Constantine's predecessor, Diocletian, sometimes known as the "Second Father of the Roman Empire". The success of Constantine's empire has often been attributed to the work and reforms of Diocletian, but there have been very few studies of the man beyond simple biography. -

A Brief History of Emperor Constantine

www.redcrossofconstantinesurrey.co.uk A Brief History of Emperor Constantine Constantine the Great, also known as Constantine I, was a REIGN Roman Emperor who ruled between 306 and 337 AD. Born on the 25 July 306 AD – 29 October 312 AD territory now known as Niš, located in Serbia, he was the son of (Caesar in the west; self-proclaimed Flavius Valerius Constantius, a Roman Army officer of Illyrian Augustus from 309; recognized as such in origins. His mother Helena was Greek. His father became Caesar, the east in April 310.) the deputy emperor in the west, in 293 AD. 29 October 312 – 19 September 324 Constantine was sent east, where he (Undisputed Augustus in the west, senior rose through the ranks to become a Augustus in the empire.) military tribune under Emperors 19 September 324 – 22 May 337 Diocletian and Galerius. (As emperor of whole empire.) In 305, Constantius raised himself GENERAL INFORMATION to the rank of Augustus, senior Predecessor Constantius I western emperor, and Constantine was recalled west to campaign Successor Constantine II under his father in Britannia (Britain). Constantine was acclaimed as Born 27 February c. 272 emperor by the army at Eboracum Naissus, Moesia (modern-day York) after his father’s Superior, Roman Empire death in 306 AD. He emerged victorious in a series of civil wars against Emperors Died 22 May 337 (aged 65) Maxentius and Licinius to become sole Nicomedia, Bithynia, ruler of both west and east by 324 AD. Roman Empire As emperor, Constantine enacted administrative, Burial Church of the Holy financial, social, and military reforms to strengthen the empire. -

THE FRACTURE of IMPERIAL ROME the Rise and Fall of the Gallic Empire 260-274 CE a Set of Eight Bronze Coins

THE FRACTURE OF IMPERIAL ROME The Rise and Fall of the Gallic Empire 260-274 CE A Set of Eight Bronze Coins Coin type and grade may vary Order code: 8GALLICEMPBOX somewhat from image Beginning with the reign of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, the Roman Empire enjoyed two full centuries of peace and prosperity. The Pax Romana was unprecedented in both duration and territory—at its height, Rome controlled the entire Mediterranean region: most of Europe, including Britannia; all of North Africa from Gibraltar to Egypt; and a vast swath of the Middle East stretching into Mesopotamia and the Caucasus. Governing that many diverse populations so effectively, and for so long, is a feat unrivaled in the annals of history. To do so, the Romans established the most efficient system of administration the world had ever known. Career bureaucrats—prefects, politicians, tax collectors—maintained the system regardless of who was seated on the throne. During the Pax Romana, Rome also boasted a series of strong, stable emperors. Although there were periods of unrest, these tended to be short. After the death of Nero, three family dynasties provided the Empire with a consistent succession of emperors. By the third century CE, the empire began to show signs of collapse. A parade of emperors took the throne, mostly from the ranks of the military. Years of civil war and open revolt led to an erosion of territory. In the year 260, in a battle on the Eastern front, the Emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by the hated Persians. He died in captivity, and his corpse was stuffed and hung on the wall of the palace of the Persian king. -

Commodus-Hercules: the People’S Princeps

Commodus-Hercules: The People’s Princeps Olivier Hekster History has not been kind to Lucius Aurelius Commodus. Cassius Dio men tioned how ‘Commodus, taking a respite from his amusement and sports, turned to murder and was killing off the prominent men’, before describing the emperor as ‘superlatively mad’. The author of the fourth-century Histo ria Augusta continued the negative tradition, and summarised Commodus as being, from his earliest childhood onwards, ‘base and dishonourable, and cruel and lewd, and moreover defiled of mouth and debauched’.1 Gibbon was shocked to find that his perfect princeps, Marcus Aurelius, had left his throne to such a debased creature and commented that ‘the monstrous vices of the son have cast a shade on the purity of the father’s virtues’.2 More re cently, the latest edition of the Oxford Classical Dictionary summarises Earlier versions of this paper were delivered at the ‘Bristol Myth Colloquium’ (14-16 July 1998) and the seminar Stadtkultur in der römischen Kaiserzeit at the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut in Rome (24-1-2000). My gratitude to the organisers for inviting me, and to all participants for their comments. Spe cial thanks go to Professors Fergus Millar, Thomas Wiedemann and Wolf Lie- beschuetz, who have kindly read earlier drafts of this article, and to Professor Luuk de Blois and Dr Stephan Mols for their help during the research upon which much of this article is based. Their comments have been of great help, as was the criticism of the editors and readers of SCI. This paper will appear, in alternative form, as part of Ο. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 11-09-2006 I, Mark Andrew Atwood, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: The Department of Classics It is entitled: Trajan’s Column: The Construction of Trajan’s Sepulcher in Urbe This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Peter van Minnen William Johnson Trajan’s Column: The Construction of Trajan’s Sepulcher in Urbe A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By MARK ANDREW ATWOOD B.A., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 2004 Committee Chair: Dr. Peter van Minnen Abstract Eutropius (8.5.2) and Dio (69.2.3) record that after Trajan’s death in A.D. 117, his cremated remains were deposited in the pedestal of his column, a fact supported by archeological evidence. The Column of Trajan was located in urbe. Burial in urbe was prohibited except in certain circumstances. Therefore, scholars will not accept the notion that Trajan overtly built his column as his sepulcher. Contrary to this opinion, I argue that Trajan did in fact build his column to serve as his sepulcher. Chapter 1 examines the extensive scholarship on Trajan’s Column. Chapter 2 provides a critical discussion of the relevant Roman laws prohibiting urban burial. Chapter 3 discusses the ritual of burial in urbe as it relates to Trajan. Chapter 4 identifies the architectural precedent for Trajan’s Column and precedent for imperial burials in urbe.