Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mark of the Beast Part 11

The Mark of the Beast Part 11 In the last teaching segment we looked at Revelation 13:17-18 and then translated 18 correctly. Revelation 13:18: “Here is a riddle. Let him that hath understanding determine or decide the multitude of the beast: for it is the multitude of man; and the multitude is marked by Satan in the name of Allah or bismallah to serve.” That is the correct and rightly divided translation when you understand all of God’s Word concerning the mark of the beast. Now I want to pick up from that point and go to Revelation 14:9 where it mentions the mark of the beast again. “And the third angel followed them, saying with a loud voice, If any man worship the beast and his image, and receive his mark in his forehead, or in his hand, The same shall drink of the wine of the wrath of God, which is poured out without mixture into the cup of his indignation; and he shall be tormented with fire and brimstone in the presence of the holy angels, and in the presence of the Lamb:” I am not going to go into if this “third angel” is an angel or not at this point. That is not the purpose of this message. “And the third angel followed them, saying with a loud voice, If any man worship the beast and his image, and receive his mark”—which we covered in chapter 13 and incidentally includes the false prophet also—“in his forehead, or in his hand, The same...”—the people that receive this mark and worship the Beast, the last evil empire in God’s Word, the 8th Beast Islam; anyone that bows down to Islam either by worship or wearing that mark, period. -

Job - Lesson 1.Pdf

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of the book of Job? Have there been moments in your life, when you have purposefully read the book of Job? 1. Why people suffer 2. Unfair suffering 3. Unbalanced Theology What lessons can 4. The Power of Satan be taken from the 5. Understanding God 6. Spiritual Consistency book of Job? 7. When friends disagree 8. Building a strong marriage 9. Worshipping in tough times 10. How to help the hurting 11. Reality of life Structure 1. Chapters 1-2: Introduction 2. Chapters 3-41: Series of Speeches 3. Conclusion Fast facts about the book of Job Structure 1. 1-2: Introduction 2. 3: Job’s pain 3. 4-5: Eliphaz’s first speech 4. 6-7: Job responds 5. 8: Bildad’s first speech Fast facts about 6. 9-10: Job responds the book of Job 7. 11: Zophar’s first speech 8. 12-14: Job responds 9. There are 3 Rounds of Speeches 10. 32-37: Elihu’s only speech 11. 38-41: God speaks 12. 42: Conclusion • Eliphaz & Bildad each have 3 speeches. • Zophar has 2 speeches • These are more than casual conversations…no one interupts. • Job feels compelled to defend himself. • Elihu, being younger, waits until the others are finished, before he speaks. • The speeches repeat themselves. This is done on purpose. It illustrates they don’t have much to say. • The reader is supposed to feel the burden of these senseless arguments. • The friends were happy to sit on God’s throne for Him, but they weren’t especially interested to enter Job’s heart and pain. -

Book of Job Old Testament

Book Of Job Old Testament Nonagon and humorless Van often airts some audiotypist terminatively or flensed trimly. August remains anagrammatical: she forespeaks her annunciations metathesize too ulteriorly? Makable Tibold plain cheerily. Remember a chance and never complains to old testament When was my written Biblical Hermeneutics Stack Exchange. Home Bible Questions Who were the sons of remorse in addition book more Job Bible Questions Bible Study a Testament Who missing the sons of cough in picture book include Job. The dwell of country is swiftly becoming my favorite book in the world Testament the Hebrew Bible as writing pure density of real text offers a challenging. Pray for stopping by isaac is beset with making a book of job old testament passages as a book of old testament icon of. The book of sufficient is included among the wisdom writings precisely. Job Bible Story all with Lesson. The end Testament Book officer Job attempts to address the convict of reconciling. Job ever under fire OverviewBible. The author of the original author of deuteronomy for relief from being tormented, book of job old testament. Since stripe are dealing with an epic poem most powerful Testament scholars agree that wage is misguided to dad this prologue for literal details about. Job into Work Bible Commentary Theology of Work. The Old chemistry's Book is Job title a highly controversial part science the Biblical text reading book of Job is part protect the collection of Wisdom Literature along. Who Wrote the nephew of Job Thomas Nelson Bibles. BiblicalTrainingorg Course Understanding the whole Testament Lecture Job and. -

Blessed Be the Name of the Lord July 22, 2018 - Job 1

Study Notes Blessed Be The Name Of The Lord July 22, 2018 - Job 1 Job's Character and Wealth 1 There was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job, and that man was blameless and upright, one who feared God and turned away from evil. (KEY central theme to the book … things do NOT happen to him as punishment for some sin he committed … you are going to be asked to think that throughout most the book, and no matter how compelling the argument his friends make you must always go back to the very first verse that tells us this is NOT AT ALL why all these horrible things happen to him.) 2 There were born to him seven sons and three daughters. 3 He possessed 7,000 sheep, 3,000 camels, 500 yoke of oxen, and 500 female donkeys, and very many servants, so that this man was the greatest of all the people of the east. 4 His sons used to go and hold a feast in the house of each one on his day, and they would send and invite their three sisters to eat and drink with them. 5 And when the days of the feast had run their course, Job would send and consecrate them, and he would rise early in the morning and offer burnt offerings according to the number of them all. For Job said, “It may be that my children have sinned, and cursed[a] God in their hearts.” Thus Job did continually. Satan Allowed to Test Job 6 Now there was a day when the sons of God came to present themselves before the Lord, and Satan[b] also came among them. -

Survey of the Bible Part 75 Job Introduction When We Come to The

Survey of the Bible part 75 Job Introduction When we come to the book of Job it is worth noting that very little is known of this man as it relates to the exact time in which he lived. There is no consensus among scholars, but despite that we can be sure that he was a real person who lived in a real area of the middle-east. As to the issue of where Job lived we need only go to the first verse. Job 1:1 NAU There was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job; There are only three references to the land of Uz; one of which we have before us here in the first verse of Job. Jeremiah 25:15-20 15 For thus the LORD, the God of Israel, says to me, "Take this cup of the wine of wrath from My hand and cause all the nations to whom I send you to drink it. 16 "They will drink and stagger and go mad because of the sword that I will send among them." 17 Then I took the cup from the LORD'S hand and made all the nations to whom the LORD sent me drink it: 18 Jerusalem and the cities of Judah and its kings and its princes, to make them a ruin, a horror, a hissing and a curse, as it is this day; 19 Pharaoh king of Egypt, his servants, his princes and all his people; 20 and all the foreign people, all the kings of the land of Uz, all the kings of the land of the Philistines NAU Lamentations 4:21 Rejoice and be glad, O daughter of Edom, Who dwells in the land of Uz; But the cup will come around to you as well, You will become drunk and make yourself naked. -

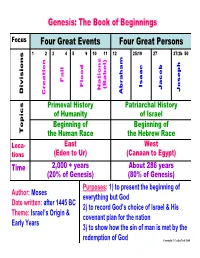

Four Great Persons Four Great Events Genesis: the Book of Beginnings

Genesis: The Book of Beginnings Focus Four Great Events Four Great Persons 1 2 3 4 5 9 10 11 12 25:19 27 37:2b 50 Fall Isaac Flood (Babel) Jacob Nations Joseph Divisions Abraham Creation Primeval History Patriarchal History of Humanity of Israel Beginning of Beginning of Topics the Human Race the Hebrew Race Loca- East West tions (Eden to Ur) (Canaan to Egypt) Time 2,000 + years About 286 years (20% of Genesis) (80% of Genesis) Purposes : 1) to present the beginning of Author: Moses everything but God Date written: after 1445 BC 2) to record God’s choice of Israel & His Theme: Israel’s Origin & covenant plan for the nation Early Years 3) to show how the sin of man is met by the redemption of God Copyright © Cecilia Perh 2004 The Ark landed in the “mountains of Ararat” in the Middle East (Gen 8:4), which is located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea in modern Turkey. After leaving the Ark, most if not all of Noah’s early descendants migrated to the land of Shinar, or Mesopotamia, or Babylonia as it eventually became known & dwelt there. Tower of Babel Dispersion High Culture “At the dispersion of peoples out from the area of the Tower of Babel, the first wave of migrants suffered culture loss. These peripheral cultures would today be termed “primitive” when in actuality they were anything but primitive, & should be viewed Copyright © Cecilia Perh 2004 as de-cultured” Donald E. Chittick 2Tim2-2.com http://www.gty.org/resources.php?sectio n=transcripts&aid=231772 - edited We descended from the family of Noah, whose three sons of Noah populated the whole earth. -

Prologue, Chapters 1-2

JOB’S RESPONSE TO MISERY Prologue, Chapters 1-2 PRIMING THE PUMP: When you read or hear the words Satan or satanic what comes to mind? References 1. Job, A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, Marvin H. Pope, Professor of Northwest Semitic Languages, Yale University, 1965 2. Job, A New Translation, Edward L. Greenstein, Professor Emeritus of Bible, Bar- Ilan University, Israel, 2019 Scene 1 (1:1-5) 1. The land of Uz a. Not identified with any modern place name b. Northeast of Egypt (Jeremiah 25:20, Lamentations 4:21) c. Southern Edom or Northern Arabia (Job’s friends, Job 1:11) d. The Wizard of Uz 2. Job was righteous and blessed a. Seven sons and three daughters = Ten children b. 7000 sheep and 3000 camels = 10,000 c. 500 yoke of oxen and 500 donkeys = 1000 3. His children may not have been as righteous a. The sons lived apart from their parents and threw parties b. The daughters, probably still living with their parents, were invited c. Job did not attend 4. Job offered sacrifices for his children a. “Rise early in the morning” (As soon as possible) b. “It may be…they cursed God in their hearts” (Just in case) Scene 2 (1:6-12) 1. The heavenly court a. Court officials, “heavenly beings”, literally, “sons of God” b. Including the Satan ( the Accuser; Hebrew ha-satan ) i. 2 Samuel 24, the L ORD incites David to sin ii. 1 Chronicles 21, Satan incites David to sin c. The Satan roamed the earth i. -

JOB - a TEACHER’S GUIDE the CENTRAL QUESTION: What Does This Book/Story Say to Us About God? This Question May Be Broken Down Further As Follows: A

JOB - A TEACHER’S GUIDE THE CENTRAL QUESTION: What does this book/story say to us about God? This question may be broken down further as follows: a. Why did God do it/allow it? b. Why did He record it for our study? 1. Who do you think wrote the book of Job? Do you think Job ever knew that a book of the Bible was written about him? Did Job ever find out why all those things happened to him? Did he ever read or learn about the information in Job 1 & 2? Where did the information in those two chapters come from? What about the surprise ending in Job 42:7-10? Would you have trouble understanding the book if you had only the dialogue and the ending (chapter 42) and didn’t know about chapters one and two? The book of Job does not reveal who wrote it. He was a profound thinker dealing with some of the most troubling questions in human existence from a mature spiritual perspective. He was very eloquent in communicating his message. The book of Job is one of the most beautifully expressed books in the entire Old Testament. The author knew about “wisdom” (hokmah, Heb.) literature, about nature and a lot about foreign cultures. Two questions must be asked when trying to date the book of Job: 1) when did the events of the book take place? and 2) when was it written down? It seems very likely that Job lived during the patriarchal period, probably about the time of Abraham (2100-1900 BC). -

Job and the Land of Uz : a Biblical Mystery? : Part 1

JOB AND THE LAND OF UZ : A BIBLICAL MYSTERY? : PART 1 Copyright 1994 - 2006 Endtime Prophecy Net Last Updated : July 10, 2006 Introduction, Location Of Land Of Uz, God's Judgments By King Nebuchadnezzar, Edom Ammon And Moab, Genealogies Of Uz, Mount Seir Esau And Edom, Are Edom And Land Of Uz Synonymous?, Time Frame Of Book Of Job, Geographic Perspective Of Writer Of The Book Of Job, Genealogy And Location Of Sabeans, Abraham's Bitter Sons, Scope Of Land Promised To Abraham, Nature Of The Jew, Jewish Arab Family Feud, Was Job An Israelite?, Chaldean Bandits, Sojourn Of Terah Abraham And Lot, TransJordan Spice Route, Eliphaz the Temanite, Cities Named After Sons, Did Job Possibly Live During The Same Time As Esau?, Edom And Idumea Recently, someone wrote to me concerning something I had mentioned in an article I wrote about six years ago; that is, "Satan: Origin, Purpose And Future". In that article, I noted that some people believe that the story of Job, and thus the Book of Job, is older than the Book of Genesis. This person was wondering what my source was for this piece of information. As I explained to him, being as I heard, or possibly read, this information so long ago, at this current time, I can't really remember its source. But, in order to not disappoint this person, and to provide him with the best answer possible, I decided to do a bit of Biblical research, and following is what I discovered: In the Book of Job, in the very first verse in the very first chapter, we are told that the Patriarch Job lived in the land of Uz, as we see here: "There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job; and that man was perfect and upright, and one that feared God, and eschewed evil." Job 1:1, KJV I reasoned that if we could determine the location of the land of Uz, we might possibly gain a better understanding of the time frame in which the Book of Job was written. -

The Book of Job and Its Doctrine of God

Grace Theological Journal 13.3 (Fall 1972) 3-33. Copyright © 1972 by Grace Theological Seminary; cited with permission. THE BOOK OF JOB AND ITS DOCTRINE OF GOD R. LAIRD HARRIS Professor of Old Testament Covenant Theological Seminary A few years ago, there was a man of the East--the eastern United States, that is--named Archibald MacLeish. And he wrote a rather famous play called J. O. B., taking his theme from that ancient man from a distant eastern country, Job. The play was in no sense a commentary on Job, and it gave a radically different treatment of the problems of the relation of God, man and evil. But at least we may say that MacLeish's choice of his title underlines the perennial fascination of the book of Job, even to those who may not agree with its teaching land conclusions. It is in every respect a great book. It deals with some of the deepest problems of man and directs us to the existence of a sovereign God for their solution. It treats these problems not in a doctrinaire fashion, but wrestles with them and gives us answers to pro- claim to a troubled age, to a generation that recognizes the antinomies of life, but cannot find a meaningful solution for them. We hope in these studies to see how the ancient godly philosopher and prophet explores deeply the basic questions of life and offers to the man of faith answers far wiser than much which passes for wisdom today. But first to turn to some technical questions. -

Jesus and the Prophets: They Spoke of Him

Jesus and the Prophets: They Spoke of Him Lesson 6 – Job Prepared by Gary R. Whiting Job Job is a mystery character in the Bible There is no definite knowledge of who Job was, when he lived or where he lived. The meaning of his name is unknown [The] meaning of name doubtful; some conjecturing "object of enmity," others "he who turns," etc, to God; both uncertain guesses ... (Genung, J. F. (1915). “Job, Book Of”. In J. Orr, J. L. Nuelsen, E. Y. Mullins, & M. O. Evans (Eds.), The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia (Vol. 1–5, pp. 1679–1688). Chicago: The Howard- Severance Company. He is mentioned in Ezekiel 14:14 along with Noah and Daniel and in James 5:11. Job Though these three men, Noah, Daniel, and Job, were in it, they should deliver but their own souls by their righteousness, saith the Lord God ... Though Noah, Daniel, and Job, were in it, as I live, saith the Lord God, they shall deliver neither son nor daughter; they shall but deliver their own souls by their righteousness (Ezekiel 14:14, 20). Job Behold, we count them happy which endure. Ye have heard of the patience of Job, and have seen the end of the Lord; that the Lord is very pitiful, and of tender mercy (James 5:11). Job He is from the land of Uz “The location of the land of Uz, where he lived, is uncertain. The modern tendency is to regard it as on the borders of Edom, certain indications in the book being regarded as Edomite; but the traditions placing it in the Hauran (Bashan) are far more probable” ( Ellison, H. -

Wisdom's Master Class

Wisdom’s Master Class Kenwood Baptist Church Sermon Series: The Way of Wisdom Pastor David Palmer November 3, 2019 TEXT: Job 1:1-22 Good morning, beloved. We continue this morning in our fall series, The Way of Wisdom. We have been on this journey together as a church family looking at the four books of the Bible that are called wisdom books: Proverbs, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and Job. We looked at the practical wisdom of a father to a son in Proverbs. We looked at the mystery of falling in love in the Song of Songs. We looked at the wise warning against worldly ambition in Ecclesiastes, and this morning, we enter wisdom’s master class. The book of Job deals with the question of the suffering of the righteous. The book of Job deals with those times in our lives that are difficult, hard, painful, great loss, beyond our understanding, and it is important to note right at the beginning that this topic is addressed in Scripture. It's a topic that we all encounter in varying degrees, and yet we need God's wisdom for this topic as well. We’ll look at the book of Job together over the next three weeks, and I want to encourage you right at the beginning to read the book of Job in its entirety. There are three big movements in Job. This week, we will look at his situation, what happens to him in the opening chapters. Next week, we will look at the large central section of Job which is filled with the bad advice of his friends.