Hariyo Ban Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

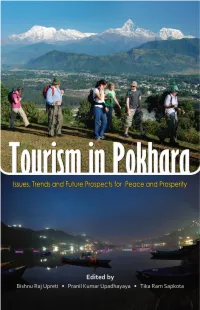

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity 1 Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tikaram Sapkota Published by Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR North-South and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research, Kathmandu Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Upadhayaya PK, Sapkota T, editors. 2013. Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity. Kathmandu: Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North- South) and Nepal Center for Contemporary Research (NCCR), Kathmandu. Copyright © 2013 PTC, NCCR North-South and NCCR, Kathmandu, Nepal All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-6169-2 Subsidised price: NPR 390/- Cover concept: Pranil Upadhayaya Layout design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed at: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover photo design: Tourists at the outskirts of Pokhara with Mt. Annapurna and Machhapuchhre on back (top) and Fewa Lake (down) by Ashess Shakya Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North-South) and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research (NCCR). Dedication To the people who contributed to developing Pokhara as a tourism city and paradise The editors of the book Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity acknowledge supports of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, co-funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions. -

![Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7316/wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-cggk-0f-if0f-if-qsf-tgwf-l-jgohgt-wild-mammals-of-the-annapurna-conservation-area-2019-127316.webp)

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area Cggk"0F{ ;+/If0f If]Qsf :Tgwf/L Jgohgt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019

Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area - 2019 ISBN 978-9937-8522-8-9978-9937-8522-8-9 9 789937 852289 National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project Khumaltar, Lalitpur, Nepal Hariyo Kharka, Pokhara, Kaski, Nepal National Trust for Nature Conservation P.O. Box: 3712, Kathmandu, Nepal P.O. Box: 183, Kaski, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5526571, 5526573, Fax: +977-1-5526570 Tel: +977-61-431102, 430802, Fax: +977-61-431203 Annapurna Conservation Area Project Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.ntnc.org.np Website: www.ntnc.org.np 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' National Trust for Nature Conservation Annapurna Conservation Area Project 2019 Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area cGgk"0f{ ;+/If0f If]qsf :tgwf/L jGohGt' Published by © NTNC-ACAP, 2019 All rights reserved Any reproduction in full or in part must mention the title and credit NTNC-ACAP. Reviewers Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah (Himalayan Nature), Dr. Naresh Subedi (NTNC, Khumaltar), Dr. Will Duckworth (IUCN) and Yadav Ghimirey (Friends of Nature, Nepal). Compilers Rishi Baral, Ashok Subedi and Shailendra Kumar Yadav Suggested Citation Baral R., Subedi A. & Yadav S.K. (Compilers), 2019. Wild Mammals of the Annapurna Conservation Area. National Trust for Nature Conservation, Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. First Edition : 700 Copies ISBN : 978-9937-8522-8-9 Front Cover : Yellow-bellied Weasel (Mustela kathiah), back cover: Orange- bellied Himalayan Squirrel (Dremomys lokriah). -

Integrated Lake Basin Management Plan of Lake Cluster of Pokhara Valley, Nepal (2018-2023)

Integrated Lake Basin Management Plan Of Lake Cluster of Pokhara Valley, Nepal (2018-2023) Nepal Valley, Pokhara of Cluster Lake Of Plan Management Basin Lake Integrated INTEGRATED LAKE BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN OF LAKE CLUSTER OF POKHARA VALLEY, NEPAL (2018-2023) Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1- 4211567, Fax: +977-1-4211868 Government of Nepal Email: [email protected], Website: www.mofe.gov.np Ministry of Forests and Environment INTEGRATED LAKE BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN OF LAKE CLUSTER OF POKHARA VALLEY, NEPAL (2018-2023) Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Publisher: Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Environment Citation: MoFE, 2018. Integrated Lake Basin Management Plan of Lake Cluster of Pokhara Valley, Nepal (2018-2023). Ministry of Forests and Environment, Kathmandu, Nepal. Cover Photo Credits: Front cover - Rupa and Begnas Lake © Amit Poudyal, IUCN Back cover – Begnas Lake © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral © Ministry of Forests and Environment, 2018 Acronyms and Abbreviations ACA Annapurna Conservation Area ADB Asian Development Bank ARM Annapurna Rural Municipality BCN Bird Conservation Nepal BLCC Begnas Lake Conservation Cooperative BMP Budhi Bazar Madatko Patan CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CF Community Forest CFUG Community Forest User Group CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora DADO District Agriculture Development Office DCC District Coordination -

Water Quality in Pokhara: a Study with Microbiological Aspects

A Peer Reviewed TECHNICAL JOURNAL Vol 2, No.1, October 2020 Nepal Engineers' Association, Gandaki Province ISSN : 2676-1416 (Print) Pp.: 149- 161 WATER QUALITY IN POKHARA: A STUDY WITH MICROBIOLOGICAL ASPECTS Kishor Kumar Shrestha Department of Civil and Geomatics Engineering Pashchimanchal Campus, Pokhara E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Obviously, water management is challenging issue in developing world. Dwellers of Pokhara use water from government supply along with deep borings and other sources as well. Nowadays, people are also showing tendency towards more use of processed water. In spite of its importance, quality analysis of water has been less emphasized by concerned sectors in our cities including Pokhara. The study aimed for qualitative analysis of water in the city with focus on microbiological aspects. For this purpose, results of laboratory examination of water samples from major sources of government supply, deep borings, hospitals, academic institutions as well as key water bodies situated in Pokhara were analyzed. Since water borne diseases are considered quite common in the area, presence of coliform bacteria was considered for the study to assess the question on availability of safe water. The result showed that all the samples during wet seasons of major water sources of water in Pokhara were contaminated by coliform bacteria. Likewise, in all 20 locations of Seti River, the coliform bacteria were recorded. Similar results with biological contamination in all samples were observed after laboratory examination of more than 60 locations of all three lakes: Phewa Lake, Begnas Lake and Rupa Lake in Pokhara. The presence of such bacteria in most of the water samples of main sources during wet seasons revealed the possibilities of spreading water related diseases. -

Prithvi Academic Journal

PRITHVI ACADEMIC JOURNAL Prithvi Academic Journal (A Peer-Reviewed, Open Access International Journal) ISSN 2631-200X (Print); ISSN 2631-2352 (Online) Volume 3; May 2020 Trends of Temperature and Rainfall in Pokhara Upendra Paudel, Associate Professor Department of Geography, Prithvi Narayan Campus Tribhuvan University, Nepal ABSTRACT Climate is an average condition of temperature, humidity, air pressure, wind, precipitation and other meteorological elements. It is a changing phenomenon. Natural processes and human activities have helped change the climate. Temperature is a vital element of climate, which fluctuates in the course of time and leads to change other elements of the whole climate. An attempt has been made to analyze the pattern of temperature and rainfall of Pokhara with the help of the two decades’ temperature and rainfall conditions obtained from the station of Pokhara airport. The increasing trend of temperature and the decreasing trend of rainfall might be the symbol of climatic modification. This trend refers to some changes in the climatic condition that may affect water resources, vegetation, forests and agriculture. KEYWORDS: Adaptation, climate, climatic modification, desertification, environmental problem, fluctuation, greenhouse gases INTRODUCTION Climate is an aggregate of atmospheric conditions including, humidity, air pressure, wind, precipitation and other meteorological elements in a given area over a long period of time (Critchfield, 1990). It is not ever static but a changeable phenomenon. Such type of change occurs in quality and quantity of the components of climate like temperature, air pressure, humidity, rainfall, etc. Natural and man-induced factors are responsible for the modification of climate. It is a global issue faced by every living thing of the world. -

South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation Airport Capacity Enhancement Project

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 38349-031 October 2020 Proposed Loan Nepal: South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation Airport Capacity Enhancement Project Distribution of this document is restricted until it has been approved by the Board of Directors. Following such approval, ADB will disclose the document to the public in accordance with ADB's Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 7 October 2020) Currency unit – Nepalese rupee/s (NRe/NRs) NRe1.00 = $0.008527 $1.00 = NRs117.27 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CAAN – Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal COVID-19 – coronavirus disease EMP – environmental management plan EMR – environmental monitoring report GASP – Global Aviation Safety Plan GBA – Gautam Buddha Airport GESI – gender equality and social inclusion ha – hectare ICAO – International Civil Aviation Organization MOCTCA – Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation O&M – operation and maintenance PAM – project administration manual SASEC – South Asia Subregional Economic Cooperation TIA – Tribhuvan International Airport NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Nepal and its agencies ends on 15 July. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2020 ends on 15 July 2020. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. Vice-President Shixin Chen, Operations 1 Director General Kenichi Yokoyama, South Asia Department (SARD) Director Ravi Peri, Transport and Communications Division (SATC), SARD Team leader Kai Wei Yeo, Senior Transport Specialist, SATC, SARD Co-Team leader Naresh Pradhan, Senior Project Officer (Transport), Nepal Resident Mission, SARD Team members Arlene Ayson, Senior Operations Assistant, SATC, SARD Sin Wai Chong, Transport Specialist, SATC, SARD Sajid Raza Zaffar Khan, Financial Management Specialist, Portfolio, Results, and Quality Control Unit; Office of the Director General, SARD Vergel M. -

Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning In

VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL IMPLEMENTING AGENCY IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS SUPPORTED BY Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation, Department of Forests UNE P Empowered lives. Resilient nations. VULNERABILITY AND I M PAC T S A SSESSMENT FOR A DA P TAT I O N P LANNING IN PA N C H A S E M O U N TA I N E C O L O G I C A L R E G I O N , N EPAL Copyright © 2015 Mountain EbA Project, Nepal The material in this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit uses, without prior written permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. We would appreciate receiving a copy of any product which uses this publication as a source. Citation: Dixit, A., Karki, M. and Shukla, A. (2015): Vulnerability and Impacts Assessment for Adaptation Planning in Panchase Mountain Ecological Region, Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal: Government of Nepal, United Nations Environment Programme, United Nations Development Programme, International Union for Conservation of Nature, German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal. ISBN : 978-9937-8519-2-3 Published by: Government of Nepal (GoN), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) and Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal (ISET-N). -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Enterprises for Self Employment in Banke and Dang

Study on Enterprises for Self Employment in Banke and Dang Prepared for: USAID/Nepal’s Education for Income Generation in Nepal Program Prepared by: EIG Program Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry Shahid Sukra Milan Marg, Teku, Kathmandu May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENS Page No. Acknowledgement i Executive Summary ii 1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 9 2 Objective of the Study ....................................................................................................... 9 3 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Desk review ............................................................................................................... 9 3.2 Focus group discussion/Key informant interview ..................................................... 9 3.3 Observation .............................................................................................................. 10 4 Study Area ....................................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Overview of Dang and Banke district ...................................................................... 10 4.2 General Profile of Five Market Centers: .................................................................. 12 4.2.1 Nepalgunj ........................................................................................................ -

Women's Agency in Relation to Population and Environment in Rural

Women’s Agency in Relation to Population and Environment in Rural Nepal Narayani Tiwari Promotor Prof. Dr. A. Niehof Hoogleraar Sociologie van Consumenten en Huishoudens Co-promotor Dr. L.L. Price Universitair hoofddocent leerstoelgroep Sociologie van Consumenten en Huishoudens Promotiecommissie Prof. Dr. L.E. Visser Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. I. Hutter Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Prof. Dr. D.R. Dahal Tri-bhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal Dr. Ir. M.Z. Zwarteveen Wageningen Universiteit Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool Mansholt Graduate School of Social Science Women’s Agency in Relation to Population and Environment in Rural Nepal Narayani Tiwari Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 4 oktober 2007, des ochtends om 11.00 uur in de Aula Women’s agency in relation to population and environment in rural Nepal / Narayani Tiwari. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University (2007). With references – With summaries in English and Dutch ISBN 978-90-8504-696-7 Subject headings: women, agency, population, environment, livelihood, food security, Gurung, Nepal. Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to the institutions and individuals who contributed to the successful completion of this research. I would like to thank Wageningen University and Research Centre (WUR) for granting me a Sandwich PhD fellowship that enabled me to embark on the PhD track. I would also like to acknowledge the generous financial support of the Neys-Van Hoogstraten Foundation (NHF) for the fieldwork and the thesis editing. Without the support of NHF the research could not have been carried out. -

ESMF – Appendix

Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) - Appendix 30 March 2020 Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Appendix Appendix 1: ESMS Screening Report - Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Appendix 2: Rapid social baseline analysis – sample template outline Appendix 3: ESMS Screening questionnaire – template for screening of sub-projects Appendix 4: Procedures for accidental discovery of cultural resources (Chance find) Appendix 5: Stakeholder Consultation and Engagement Plan Appendix 6: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 7: Social Impact Assessment (SIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 8: Developing and Monitoring an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) - Guidance Note Appendix 9: Pest Management Planning and Outline Pest Management Plan - Guidance Note Appendix 10: References Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) 2 Appendix 1 ESMS Questionnaire & Screening Report – completed for GCF Funding Proposal Project Data The fields below are completed by the project proponent Project Title: Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Project proponent: IUCN Executing agency: IUCN in partnership with the Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management (Nepal) and -

Table of Province 05, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Rukum East District 1,020 2,753 1,516 1,237 50101PUTHA UTTANGANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 276 825 501 324 50102SISNE RURAL MUNICIPALITY 464 1,164 620 544 50103BHOOME RURAL MUNICIPALITY 280 764 395 369 Rolpa District 5,096 15,651 8,518 7,133 50201SUNCHHAHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 302 2,231 1,522 709 50202THAWANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 244 760 362 398 50203PARIWARTAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 457 980 451 529 50204SUKIDAHA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 408 408 128 280 50205MADI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 407 881 398 483 50206TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 372 1,186 511 675 50207ROLPA MUNICIPALITY 1,160 3,441 1,763 1,678 50208RUNTIGADHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 560 3,254 2,268 986 50209SUBARNABATI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 882 1,882 845 1,037 50210LUNGRI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 304 628 270 358 Pyuthan District 5,632 22,336 12,168 10,168 50301GAUMUKHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 431 1,716 890 826 50302NAUBAHINI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 621 1,940 1,059 881 50303JHIMARUK RURAL MUNICIPALITY 568 2,424 1,270 1,154 50304PYUTHAN MUNICIPALITY 1,254 4,734 2,634 2,100 50305SWORGADWARI MUNICIPALITY 818 2,674 1,546 1,128 50306MANDAVI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 427 1,538 873 665 50307MALLARANI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 449 2,213 1,166 1,047 50308AAIRAWATI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 553 3,477 1,812 1,665 50309SARUMARANI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 511 1,620 918 702 Gulmi District 9,547 36,173 17,826 18,347 50401KALI GANDAKI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 540 1,133 653 480 50402SATYAWOTI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 689 2,406 1,127 1,279 50403CHANDRAKOT RURAL MUNICIPALITY 756 3,556 1,408 2,148