06Rev Eng Report Children Data Protection in Educational

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Higher Education in China, a Paradigm Shift from Conventional to Online Teaching

Higher Education Studies; Vol. 11, No. 2; 2021 ISSN 1925-4741 E-ISSN 1925-475X Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Higher Education in China, a Paradigm Shift from Conventional to Online Teaching Wang He1, 2, 3 & Gao Wei4, 5 1 DBA Candidate of University of Wales Trinity Saint David London Campus, UK 2 Vice President, Hankou University, Wuhan, China 3 Associate Professor & Dean of College of Media, Hankou University, Wuhan, China 4 PhD Candidate, Wuhan University of Technology, China 5 Dean of College of International Exchange, Hankou University, Wuhan, China Correspondence: Gao Wei, Dean of College of International Exchange, Hankou University, Wuhan, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 6, 2021 Accepted: March 4, 2021 Online Published: March 6, 2021 doi:10.5539/hes.v11n2p30 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v11n2p30 Abstract The entire education system, from elementary school to higher education, distorted during the lockdown period. The latest 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is not only recorded in China, but also globally. This research is an account of the online teaching paradigm assumed in the teaching method by most of universities in China and subsequent tests over the course. It looks forward to offering resources rich in knowledge for future academic decision-making in any adversity. The aim of this research paper is to explain the prerequisites for online education and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic and how to effectively turn formal education into online education through the use of virtual classrooms and other main online instruments in an ever-changing educational setting by leveraging existing educational tools. -

Frequently Asked Questions: D2L

Frequently Asked Questions: D2L 1) What are Coursepacks? 2) Which systems support Coursepacks? 3) Are Coursepacks compatible with my LMS? 4) What is available in the Coursepacks? 5) How do I access my Coursepacks file? 6) How do I import Coursepacks into the D2L LMS? 7) How do my students access the interactive eBook? 8) How do I make a quiz available to my students? 9) How long do I have access to this content? 10) My web browser prevents me from viewing a video or other content. What do I do? 11) Whom do I contact if I have trouble using my LMS? 12) Whom do I contact for support with Coursepack content? 13) When I edit a question in a quiz or within the Question Library, are my updates saved everywhere? 1) What are Coursepacks? SAGE Coursepacks provide easy to import, highly customizable, and highquality instructor and student content for your school’s learning management system (LMS). Intuitive and simple to use, SAGE Coursepacks are collections of bookspecific instructor/student resources, as well as assessments, that allow you to focus on what really matters: customizing course content to meet your students’ needs. Key Features: ✓ Delivers SAGE textbook content directly into your LMS. ✓ The intuitive and simpletouse format allows for easy course integration with minimal effort. ✓ Pedagogically robust assessment tools foster review, practice, and critical thinking, and offer a better, more complete way to measure student engagement. Tools include but are not limited to: o Diagnostic chapter PreTests and PostTests Page 2 of 10 o Test banks built on Bloom’s Taxonomy 2) Which systems support Coursepacks? The following table summarizes compatibility* of Coursepacks with various systems and browsers. -

ECDEV 602: Economic Development: Policy and Practice

ECDEV 602 Economic Development: Policy and Practice School of Environment, Enterprise and Development Faculty of Environment University of Waterloo Fall 2018 ECDEV 602: Economic Development: Policy and Practice Course Instructors: Paul Parker E-mail: [email protected] EV3 Room 4259 Phone: (519) 888-4567 ext. 32791 Office hours: Mondays, Tuesdays 1 – 2 PM (or by appointment) Tara Vinodrai E-mail: [email protected] EV3 Room 4231 Phone: (519) 888-4567 ext. 33278 Office hours: Mondays, 2:30-3:30PM, Tuesdays,1:00PM - 2:00PM (or by appointment) Class Time / Location: Tuesdays, 7:00-9:50pm EV1 350 Course Description This course is concerned with development strategies for communities and local areas, especially municipalities. The focus is on practical issues and local experience, which will in turn be related to broader concepts and theories. Included are methods of preparing community profiles, analyzing past economic and demographic trends, strategic economic planning exercises, evaluation of alternative administration models and partnerships among various actors and agencies (both public and private) involved in development practice, sustainable development to balance economic, cultural and environmental interests and evaluation techniques. Learning Objectives The key learning objectives of the course are as follows: • Introduce to students the multiple objectives (social, economic and environmental) and desired outcomes for local economic development; • Provide foundational knowledge of the various local, regional, provincial and national government agencies, as well as social economy and private sector agencies providing local economic development services in communities; • Introduce key concepts and tools, including strategic economic planning, community profiles and performance measurement; • Provide small team experience by working with a current community project; • Ensure a foundational understanding of community aspirations for a sustainable future. -

Glossary of Tools and Terms

REPRODUCIBLE Glossary of Tools and Terms This appendix includes a list of terms and resources we introduced and used throughout the book. Apps, programs, and websites are listed, as well as digital and academic terms that will aid you in lesson planning both NOW and in the future. 1:1 or one to one: Describes the number of technology devices (iPads, laptops, Chromebooks) given to each student in an academic setting; a 1:1 school has one device per each student. 1:2 or one to two: Describes the number of technology devices (iPads, laptops, Chromebooks) given to each student in an academic setting; a 1:2 school means that one technology device is available for every two students in an academic setting. Two classes may share one class set, or students may partner up to use devices. Animoto (https://animoto.com): A video-creation website and app with limited free features and options for educator accounts (see https://animoto.com/education/classroom) Annotable (www.moke.com/annotable): A full-featured image-annotation tool Appy Pie (www.appypie.com): A free do-it-yourself software tool for building apps in three easy steps Audacity (www.audacityteam.org): A free macOS and Windows software tool for editing complex audio clips AutoRap (www.smule.com/listen/autorap/79): An iOS and Android app for mixing audio tracks to create a rap; the free version allows users to choose from two beats to make a song, and the paid version allows users to choose from a large selection of beats, including new and popular songs. -

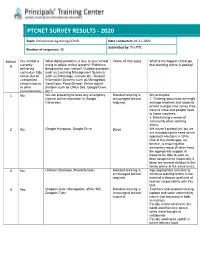

Online Learning During COVID Date Conducted: 04-21-2020 Submitted By: the PTC Number of Responses: 38

PTCNET SURVEY RESULTS - 2020 Topic: Online learning during COVID Date conducted: 04-21-2020 Submitted by: The PTC Number of responses: 38 School Our school is What digital platforms, if any, is your school ChecK all that apply What is the biggest challenge # currently using to deliver online lessons? Platforms that teaching online is posing? delivering designed by your school? Outside providers curriculum fully such as: Learning Management Systems online due to such as Schoology, Canvas etc.; Student unexpected Information Systems such as Managebac, school closure VeraCross, PowerSchool; Online digital or other platform such as Office 365, Google Drive , circumstances. etc.? 1 No We are preparing to base any emergency Blended learning is We anticipate: closure online instruction in Google encouraged but not 1. Thinking about how we might Classroom. required. manage teachers and students across multiple time zones if we have to close and people head to home countries. 2. Maintaining a sense of community when working online. 2 No Google Hangouts, Google Drive Drive We haven't started yet, but we are anticipating the need as we approach elections in Chile. One of the challenges, we believe, is ensuring that elementary aged children have the appropriate support at home to be able to work on their assignments (especially if there are several children in the family online at the same time). 3 No Unified Classroom (PowerSchool) Blended learning is Age-Appropriate activities to encouraged but not continue learning online in the required. event of a closure and level of teacher responsibility with this tasK. 4 Yes Dragons Gate, Managebac, office 365, Blended learning is Teachers and students lacKing Dragons Tube encouraged but not laptops and some connectivity required. -

State of Edtech 2019-2020:The Minds Behind What's Now

EDITOR’S LETTER rational thought and human improvement reigned. Today’s schools STATE OF EDTECH ON THE CUSP OF A of thought and practice—have an 2019-2020:THE MINDS BEHIND NEW AGE IN LEARNING opportunity to draw deeply from such an age of reason, and even more Something magical is afoot in the WHAT’S NOW & WHAT’S NEXT deeply from the sort of science seen ‘a realm of learning and education. It long time ago in a galaxy far, far away’ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Victor Rivero relates to the idea, famously posed by and increasingly appearing in our LEAD AUTHOR Mark Gura Arthur C. Clarke, “Any sufficiently midst. But with one exception: now, advanced technology is indistinguishable we have an opportunity to do it better from magic.” It coincides with a greater than before. On the cusp of a new awareness of what it means to be age, let’s make our learning come human in a machine age. And it has alive to serve us all better, and in so everything to do with the realization of doing, may we draw most deeply not LEAD AUTHOR our own humanity in the face of forces from our devices, apps, and Mark Gura that might attempt to subvert that platforms, but from the inexorable Mark taught at New York City public schools in East Harlem for through nefarious means. There was two decades. He spent five years as a curriculum developer for power of each other. —VR once a great enlightenment where the central office and was eventually tapped to be the New York City Department of Education’s director of the Office of Instructional Technology, assisting over 1,700 schools + TOP 100 INFLUENCERS in edtech FIND OUT WHY page 39 serving 1.1 million students in America’s largest school system. -

Capital Flows to Education Innovation 1 (312) 397-0070 [email protected]

July 2012 Fall of the Wall Deborah H. Quazzo Managing Partner Capital Flows to Education Innovation 1 (312) 397-0070 [email protected] Michael Cohn Vice President 1 (312) 397-1971 [email protected] Jason Horne Associate 1 (312) 397-0072 [email protected] Michael Moe Special Advisor 1 (650) 294-4780 [email protected] Global Silicon Valley Advisors gsvadvisors.com Table of Contents 1) Executive Summary 3 2) Education’s Emergence, Decline and Re-Emergence as an Investment Category 11 3) Disequilibrium Remains 21 4) Summary Survey Results 27 5) Interview Summaries 39 6) Unique Elements of 2011 and Beyond 51 7) Summary Conclusions 74 8) The GSV Education Innovators: 2011 GSV/ASU Education Innovation Summit Participants 91 2 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY American Revolution 2.0 Fall of the Wall: Capital Flows to Education Innovation Executive Summary § Approximately a year ago, GSV Advisors set out to analyze whether there is adequate innovation and entrepreneurialism in the education sector and, if not, whether a lack of capital was constraining education innovation § Our observations from research, interviews, and collective experience indicate that there is great energy and enthusiasm around the PreK-12, Post Secondary and Adult (“PreK to Gray”) education markets as they relate to innovation and the opportunity to invest in emerging companies at all stages § Investment volume in 2011 exceeded peak 1999 – 2000 levels, but is differentiated from this earlier period by entrepreneurial leaders with a breadth of experience including education, social media and technology; companies with vastly lower cost structures; improved education market receptivity to innovation, and elevated investor sophistication. -

TAB 3 Page 1

STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AUGUST 17, 2020 STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION SUBJECT Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund REFERENCE March – April 2020 The Board has received weekly updates on the federal response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the availability of funding through the CARES Act. April 27, 2020 The Board received an update on the allowable uses and amount of funds available to Idaho through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund and Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund. May 4, 2020 The Board directed staff to move forward with data analysis for the discussed proposals and to identify sources of funds for those proposals. June 10, 2020 The Board approved the use of the ESSER 10% SEA reserve funds for grants to local education agencies for devices, connectivity, infrastructure, adaptive technology, learning management system and PD around remote instruction and a request to the Coronavirus Financial Advisory Committee for $30M that could be used for the same purpose. July 15, 2020 The Board approved a methodology and grant application for $30,000,000 from Idaho’s relief funds through the Governor’s Coronavirus Financial Advisory Committee BACKGROUND/DISCUSSION The CARES Act allowed the SEA to reserve up to 10 percent of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) Fund for grants to LEAs to be used for emergency needs as determined by the SEA to address issues responding to COVID-19. These funds must be awarded by May 18, 2021, and expended by September 30, 2022. At its July 15, 2020, meeting, the Board adopted the funding distributions, which included $3.785 million for distance/blended learning with a priority for a Learning Management System (LMS). -

Using a Learning Management System to Promote Self-Regulated Learning in a Flipped Classroom

Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology, Vol. 9, Special Issue, pp. 3-18. doi: 10.14434/jotlt.v9i1.29375 Using a Learning Management System to Promote Self-Regulated Learning in a Flipped Classroom Grace Onodipe Georgia Gwinnett College [email protected] Jared Keengwe University of North Dakota [email protected] Adrienne Cottrell-Yongye Georgia Gwinnett College [email protected] Abstract: The inherent structure of the flipped classroom supports a learning environment that promotes students’ self-regulated learning. In this article, we focus on how a learning management system (LMS), in this case BrightSpace D2L, plays a key role in supporting all aspects of the flipped classroom. We discuss how preclass assignments help students give their learning some forethought and plan accordingly; frequent formative assessments and feedback permit students to monitor their progress in the classroom; students control what study resources they choose to use; and students have ample opportunities to reflect regularly on their work. Further, we explore how learning logs (a form of reflective writing), with the LMS Journaling and Dropbox features, are used to keep track of students’ journal entries as well as demonstrate how college instructors have used an LMS to motivate and encourage students to develop self-regulated learning. A qualitative analysis of students’ writing is provided to illustrate gains in self-regulation. Keywords: flipped learning, self-regulated learning, reflective writing, learning management system, LMS. -

Lms Market Dynamics

BIG PICTURE LMS MARKET DYNAMICS Spring 2016 Edition Provided by MindWires LLC http://www.mindwires.com/ Powered by: by © 2016, MindWires LLC. All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction or sharing is strictly prohibited (see http://mfeldstein.com/lms-subscription-terms-conditions/ for details). Information is based on best available resources. Opinions reflect judgment at the time and are subject to change. MindWires is a trademark of MindWires LLC. All other trademarks are the property of their respective companies. To purchase additional subscriptions for access to this report, go to http://mfeldstein.com/lms-subscription/. LMS MARKET DYNAMICS | 2 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Purpose and Organization of Report 3 Executive Summary 4 Past to Present 5 Section Summary 5 The Past: The Shaping of a Market 5 The Road to Now: A Market in Transition 10 Market Share Today 16 Some Open Questions 20 Drivers of Change 22 Section Introduction and Summary 22 Changes In Product Design 23 New Markets Bring New Opportunities and Threats 30 Further Out on the Horizon 34 The Next Twelve Months 36 Will There Be More Elective Migration? 36 Will There Be Different Winners and Losers? 37 Will the Growth in Other Markets Change Platform Sustainability? 38 Appendix: Data-Gathering Methodology 39 © 2016, MindWIres LLC. Unauthorized reproduction or sharing is strictly prohibited. LMS MARKET DYNAMICS | 3 INTRODUCTION PURPOSE AND ORGANIZATION OF REPORT This report is designed help you understand the ongoing changes in adoption patterns for higher education Learning Management Systems (LMSs, also known as “Course Management Systems” or “Virtual Learning Environments”). It analyzes who is moving to or away from which platforms and how quickly they are moving. -

Elearning Platform Review: What Did We Decide?

ELearning Platform Review: What did we decide? The Blackboard Learn Software as a Service (SaaS) is the best overall solution for Framingham State University! Following an exhaustive review of eLearning platforms the recommendation of the Learning Management Task Force is to remain with Blackboard Learn but move our hosting services to a SaaS deployment or in other words “to the cloud.” The team looked closely at five Learning platforms (Blackboard Learn, Canvas, D2L, Moodle, and Schoology). Instructure's Canvas and Blackboard's Blackboard Learn solution were the finalists. Based on all of the due diligence performed over the past several months, Blackboard Learn was selected by the team tasked with the review of alternatives. In the final analysis, the move to the Blackboard Learn SaaS solution will be the least disruptive to faculty and students. It will save the University money. And, it will provide added features and functionality that address both current and anticipated needs. How was the decision made? The ELearning Platform Review began in fall 2016 and concluded in spring 2017. The Learning Management Taskforce of faculty and staff met for each milestone to review survey results, scenario based webinars, a product sandbox, faculty focus group discussion and a meeting with SGA, all to inform a detailed RFP (request for proposal) process. To inform the final recommendation, proposals were distilled using a SWOT framework based on live vendor presentations, pricing proposals, conversations with our peers and a Gartner Research Analyst who specifically focuses on learning platforms for Higher Education. What does this mean to you? The move to the Blackboard Learn SaaS solution will not require anyone to change the way they currently use Blackboard. -

Leveraging Microsoft Teams to Enable Virtual Classrooms 00:00 START

Episode 10 - Leveraging Microsoft Teams to Enable Virtual Classrooms 00:00 START OF PODCAST Amit: Good morning. Good afternoon. Good evening, listeners, wherever you are. Welcome to yet another episode of EduTech Talks with Amit and Sam. This is Amit Pawar from Microsoft here in Singapore and it's a lovely day here in Singapore. And today, I’m joined by my colleague, Sam McNeill. And we have a surprise guest, which we'll introduce in a minute. So, over to you Sam, how are you doing today? Sam: Oh, I'm doing really well, Amit, and thank you for the introduction and always fun to be recording our podcast together. It always seems to roll around very quickly and you know, I really enjoyed the last one we did with Bill Sluss from the engineering team up at Redmond around school data sync and gosh, we're starting to suddenly see, you know, a lot of different education institutes using school data sync now, right? Amit: Yeah, absolutely. In fact, you know, my last month has been very much involved with customers leveraging school data sync, to take advantage of rapid provisioning and bringing their users up to speed in terms of getting them into the right Teams and getting them up and running and productive in a very controlled yet flexible manner. So it's been a real eye-opener for me personally as I'm helping customers, across the region take advantage of our platform. So it's enabling new scenarios for them in terms of wrap it up, you know, bringing up to speed, say up to 40-50,000 users in a day.