Learning in the 'Platform Society'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Higher Education in China, a Paradigm Shift from Conventional to Online Teaching

Higher Education Studies; Vol. 11, No. 2; 2021 ISSN 1925-4741 E-ISSN 1925-475X Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Higher Education in China, a Paradigm Shift from Conventional to Online Teaching Wang He1, 2, 3 & Gao Wei4, 5 1 DBA Candidate of University of Wales Trinity Saint David London Campus, UK 2 Vice President, Hankou University, Wuhan, China 3 Associate Professor & Dean of College of Media, Hankou University, Wuhan, China 4 PhD Candidate, Wuhan University of Technology, China 5 Dean of College of International Exchange, Hankou University, Wuhan, China Correspondence: Gao Wei, Dean of College of International Exchange, Hankou University, Wuhan, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 6, 2021 Accepted: March 4, 2021 Online Published: March 6, 2021 doi:10.5539/hes.v11n2p30 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v11n2p30 Abstract The entire education system, from elementary school to higher education, distorted during the lockdown period. The latest 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is not only recorded in China, but also globally. This research is an account of the online teaching paradigm assumed in the teaching method by most of universities in China and subsequent tests over the course. It looks forward to offering resources rich in knowledge for future academic decision-making in any adversity. The aim of this research paper is to explain the prerequisites for online education and teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic and how to effectively turn formal education into online education through the use of virtual classrooms and other main online instruments in an ever-changing educational setting by leveraging existing educational tools. -

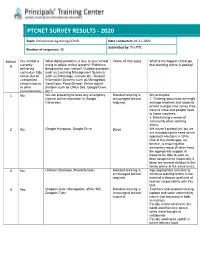

Online Learning During COVID Date Conducted: 04-21-2020 Submitted By: the PTC Number of Responses: 38

PTCNET SURVEY RESULTS - 2020 Topic: Online learning during COVID Date conducted: 04-21-2020 Submitted by: The PTC Number of responses: 38 School Our school is What digital platforms, if any, is your school ChecK all that apply What is the biggest challenge # currently using to deliver online lessons? Platforms that teaching online is posing? delivering designed by your school? Outside providers curriculum fully such as: Learning Management Systems online due to such as Schoology, Canvas etc.; Student unexpected Information Systems such as Managebac, school closure VeraCross, PowerSchool; Online digital or other platform such as Office 365, Google Drive , circumstances. etc.? 1 No We are preparing to base any emergency Blended learning is We anticipate: closure online instruction in Google encouraged but not 1. Thinking about how we might Classroom. required. manage teachers and students across multiple time zones if we have to close and people head to home countries. 2. Maintaining a sense of community when working online. 2 No Google Hangouts, Google Drive Drive We haven't started yet, but we are anticipating the need as we approach elections in Chile. One of the challenges, we believe, is ensuring that elementary aged children have the appropriate support at home to be able to work on their assignments (especially if there are several children in the family online at the same time). 3 No Unified Classroom (PowerSchool) Blended learning is Age-Appropriate activities to encouraged but not continue learning online in the required. event of a closure and level of teacher responsibility with this tasK. 4 Yes Dragons Gate, Managebac, office 365, Blended learning is Teachers and students lacKing Dragons Tube encouraged but not laptops and some connectivity required. -

State of Edtech 2019-2020:The Minds Behind What's Now

EDITOR’S LETTER rational thought and human improvement reigned. Today’s schools STATE OF EDTECH ON THE CUSP OF A of thought and practice—have an 2019-2020:THE MINDS BEHIND NEW AGE IN LEARNING opportunity to draw deeply from such an age of reason, and even more Something magical is afoot in the WHAT’S NOW & WHAT’S NEXT deeply from the sort of science seen ‘a realm of learning and education. It long time ago in a galaxy far, far away’ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Victor Rivero relates to the idea, famously posed by and increasingly appearing in our LEAD AUTHOR Mark Gura Arthur C. Clarke, “Any sufficiently midst. But with one exception: now, advanced technology is indistinguishable we have an opportunity to do it better from magic.” It coincides with a greater than before. On the cusp of a new awareness of what it means to be age, let’s make our learning come human in a machine age. And it has alive to serve us all better, and in so everything to do with the realization of doing, may we draw most deeply not LEAD AUTHOR our own humanity in the face of forces from our devices, apps, and Mark Gura that might attempt to subvert that platforms, but from the inexorable Mark taught at New York City public schools in East Harlem for through nefarious means. There was two decades. He spent five years as a curriculum developer for power of each other. —VR once a great enlightenment where the central office and was eventually tapped to be the New York City Department of Education’s director of the Office of Instructional Technology, assisting over 1,700 schools + TOP 100 INFLUENCERS in edtech FIND OUT WHY page 39 serving 1.1 million students in America’s largest school system. -

Capital Flows to Education Innovation 1 (312) 397-0070 [email protected]

July 2012 Fall of the Wall Deborah H. Quazzo Managing Partner Capital Flows to Education Innovation 1 (312) 397-0070 [email protected] Michael Cohn Vice President 1 (312) 397-1971 [email protected] Jason Horne Associate 1 (312) 397-0072 [email protected] Michael Moe Special Advisor 1 (650) 294-4780 [email protected] Global Silicon Valley Advisors gsvadvisors.com Table of Contents 1) Executive Summary 3 2) Education’s Emergence, Decline and Re-Emergence as an Investment Category 11 3) Disequilibrium Remains 21 4) Summary Survey Results 27 5) Interview Summaries 39 6) Unique Elements of 2011 and Beyond 51 7) Summary Conclusions 74 8) The GSV Education Innovators: 2011 GSV/ASU Education Innovation Summit Participants 91 2 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY American Revolution 2.0 Fall of the Wall: Capital Flows to Education Innovation Executive Summary § Approximately a year ago, GSV Advisors set out to analyze whether there is adequate innovation and entrepreneurialism in the education sector and, if not, whether a lack of capital was constraining education innovation § Our observations from research, interviews, and collective experience indicate that there is great energy and enthusiasm around the PreK-12, Post Secondary and Adult (“PreK to Gray”) education markets as they relate to innovation and the opportunity to invest in emerging companies at all stages § Investment volume in 2011 exceeded peak 1999 – 2000 levels, but is differentiated from this earlier period by entrepreneurial leaders with a breadth of experience including education, social media and technology; companies with vastly lower cost structures; improved education market receptivity to innovation, and elevated investor sophistication. -

Education Learning Management Systems Category Report Vendor

April 2019 INTERNAL USE ONLY CATEGORY REPORT Education Learning Management Systems Blackbaud onCampus Canvas Moodle Sakai Blackboard Learning Management Software D2L Brightspace PowerSchool Learning Schoology 899 8 Reviews Vendors Evaluated Education Learning Management Systems Category Report How to Use the Report Table of Info-Tech’s Category Reports provide a comprehensive evaluation of popular products in the Education Learning Management Systems market. This buyer’s guide is designed to help Contents prospective purchasers make better decisions by leveraging the experiences of real users. The data in this report is collected from real end users, meticulously verified for veracity, Data Quadrant...................................................................................................................7 exhaustively analyzed, and visualized in easy to understand charts and graphs. Each product is compared and contrasted with all other vendors in their category to create a holistic, unbiased view Category Overview ......................................................................................................8 of the product landscape. Use this report to determine which product is right for your organization. For highly detailed reports Vendor Capability Summary................................................................................ 9 on individual products, see Info-Tech’s Product Scorecard. Vendor Capabilities....................................................................................................10 -

LMS Data Quadrant Report

November 2020 DATA QUADRANT REPORT Education Learning Management Systems 938 9 Reviews Vendors Evaluated Education Learning Management Systems Data Quadrant Report How to Use the Report Table of Info-Tech’s Data Quadrant Reports provide a comprehensive evaluation of popular products in the Education Learning Management Systems market. This buyer’s guide is designed to help Contents prospective purchasers make better decisions by leveraging the experiences of real users. The data in this report is collected from real end users, meticulously verified for erv acity, Data Quadrant.................................................................................................................. 6 exhaustively analyzed, and visualized in easy to understand charts and graphs. Each product is compared and contrasted with all other vendors in their category to create a holistic, unbiased view Category Overview .......................................................................................................7 of the product landscape. Use this report to determine which product is right for your organization. For highly detailed reports Vendor Capability Summary................................................................................8 on individual products, see Info-Tech’s Product Scorecard. Vendor Capabilities......................................................................................................11 Product Feature Summary................................................................................. 23 Product Features........................................................................................................25 -

Research Study of Digital Reporting, Assessment and Portfolio Tools: Results Summary

ATA Research 2018 Research Study of Digital Reporting, Assessment and Portfolio Tools: Results Summary www.teachers.ab.ca © Copyright 2018 ISBN 978-1-927074-63-3 Unauthorized use or duplication without prior approval is strictly prohibited. Alberta Teachers’ Association 11010 142 Street NW, Edmonton AB T5N 2R1 Telephone 780-447-9400 or 1-800-232-7208 www.teachers.ab.ca Further information about the Association’s research is available from Dr Philip McRae at the Alberta Teachers’ Association; e-mail [email protected]. Research Study of Digital Reporting, Assessment and Portfolio Tools: Results Summary Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................... v Background ................................................................................................................ 1 Method........................................................................................................................ 2 Instrument .......................................................................................................... 2 Limitations .......................................................................................................... 2 Key Findings .............................................................................................................. 3 Teachers’ Workload and Professional Autonomy .......................................... 3 Instruction and Learning ................................................................................. -

FROM ANALYTICS to ADAPTIVE LEARNING for Internal Training Only

SMALLER SCALE HAS MORE SPACING INSIDE LOGOMARK LARGE SCALE HAS LESS SPACING INSIDE LOGOMARK 707271 43A89A 54575A 84A1C4 6DBEBD ECDC98 112/114/113 5/154/135 95/96/98 132/161/196 109/190/189 236/220/152 424 3282 425 659 5493 461 From Analytics to Adaptive Learning AN OVERVIEW OF K-12 BUSINESS MODELS & OPPORTUNITIES Commissioned by Intel® Education UX Group For Internal Training Only September 2015 | Prepared by Clarity Innovations FROM ANALYTICS TO ADAPTIVE LEARNING For Internal Training Only Executive Summary The emergence of “Big Data” and predictive analytics over the past few years has had a significant impact on many areas of daily life — from changes to the way baseball players are drafted to the way Wal-Mart sells Pop Tarts.1 In the finance field, “automated wealth managers” use algorithms to help customers manage their investment portfolios. Likewise, educators have been asking, “Could those same algorithms help students manage their learning?” As Knewton CEO Jose Ferreira put it, what could learners accomplish with the help of “a friendly mind-reading robot tutor in the sky?”2 Over the past few years, a number of factors, most prominently the adoption of software as a service (SaaS) tools for curriculum and testing, have coalesced to make the K-12 KEY RESEARCH FINDINGS landscape ideal for learning analytics and adaptive learning systems. 1. Education reform in The purpose of this paper is to: the U.S. is demanding • Review the landscape of education analytics and adaptive learning systems; evidence-based action • Identify the key business models being employed; and, 2. -

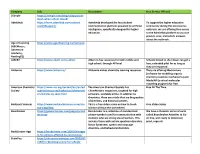

Company Link Description Free Service Offered 2Simple

Company Link Description Free Service Offered 2Simple https://2simple.com/blog/using-purple- mash-when-school-closed/ AdmitHub https://learn.admithub.com/content- AdmitHub developed the first student To support the higher education covid19support/ communication platform powered by artificial community during the Coronavirus intelligence, specifically designed for higher outbreak, we are offering free access education. to the AdmitHub platform so you can provide clear, immediate answers about the outbreak. Age of Learning https://www.ageoflearning.com/schools (ABCMouse, Adventure Academy, ReadingIQ) ALBERT https://www.albert.io/try-albert Albert.io has resources for both middle and Schools forced to shut down can get a high school, through AP level. free, extended pilot for as long as they are impacted. Alchemie https://www.alchem.ie/ Alchemie makes chemistry learning resources. They are offering Mechanisms (software for modeling organic chemistry reaction mechanisms) and ModelAR (a virtual molecular modeling program) for free. American Chemistry https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/ed The American Chemical Society has Free All The Time Society ucation/resources/highschool/chemmatt ChemMatters magazines, targeted for high ers/articles-by-topic.html schoolers, available online. In addition to chemistry, there are article that are biographies of chemists, and historical articles. Backpack Sciences https://www.backpacksciences.com/scie This is a free video series on how to teach Free Video Series nce-simplified science without the overwhelm. Boardmaker https://goboardmaker.com/pages/activit Boardmaker is a collection of standardized We have a thematic series of units ies-to-go picture symbols used for communication with called Boardmaker Activities to Go- students who are strong visual learners. -

Mobile Distance & Hybrid Education Solutions

Mobile Distance & Hybrid Education Solutions A Knowledge Pack Last updated: November 11, 2020 Author: Marisa Steinmetz, World Bank, EdTech Team Overview: What does the World Bank and its Global EdTech team do? How does this Knowledge Pack fit in? Background o World Bank’s goals o World Bank Education Technology team’s vision o World Bank’s 5 EdTech Principles o World Bank’s EdTech Approach o Overview of this Knowledge Pack on Mobile Distance & Hybrid Education Solutions Click on any hyperlink to jump directly to the section. What are the World Bank’s goals? 03 The World Bank Group has two goals: To end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity in a sustainable way. Back to section overview What is the World Bank’s Education Technology team’s vision? 04 The World Bank’s Education Technology (EdTech) team’s vision is to: Reimagine Human Connections to Transform Teaching and Learning for All Back to section overview What are the World Bank’s 5 EdTech principles? 05 1 ASK WHY: EdTech policies and projects need to be developed with a clear purpose, strategy and vision of the desired educational change. 2 DESIGN AND ACT AT SCALE FOR ALL: The design of EdTech initiatives should be flexible and user-centered, with an emphasis on equity and inclusion, in order to realize scale and sustainability for all. 3 EMPOWER TEACHERS: Technology should enhance teacher engagement with students through improved access to content, data and networks, helping teachers better support student learning. 4 ENGAGE THE ECOSYSTEM: Education systems should take a whole-of-government and multi-stakeholder approach to engage a broad set of actors to support student learning. -

Technology for Teaching and Learning: Tools You Can Use Right Now

TECHNOLOGY FOR TEACHING AND LEARNING: TOOLS YOU CAN USE RIGHT NOW Twyman, NAC2015 Janet S. Twyman UMass Medical School & the Center on Innovations in Learning CIRCA 1990 FRED S. KELLER SCHOOL, YONKERS NY • EdTech & Evidence • Evaluation Rubrics • Hands On App Reviews • Learning Management Systems • Creating Your Own • Hardware • Curation & Review Sites • Staying Informed THE PLAN FOR TODAY WHAT WE HOPE TO COVER apps resources evidence demos data accessibility safety device type os features ownership prof. dev. tech plan cost-benefit procurement full privacy/security WHAT ALSO SHOULD BE learner interest CONSIDERED & ability Go to: kahoot.it No need to download app Type in a nickname ED TECH TO ENHANCE TEACHING & LEARNING IS TECHNOLOGY EFFECTIVE? • To do what? • With whom? By whom? • Under what conditions? • With what learning outcomes? (compared to…?) http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ848688.pdf A NON-SCIENTIFIC CONSIDERATION OF THE EVIDENCE FOR MOST APPS Amount more less Opinion PerObs AB SSD RCT Type ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF EVIDENCE proactivespeech.wordpress.com/ 2012/10/10/ ipad-apps-can-support-evidence- based-practice/ http://smartyearsapps.com/ evidence-based-practice/ EVIDENCE OF EFFECTIVENESS PAUCITY OF PUBLISHED RESEARCH Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning. US DOE (2010) An introduction to the evaluation of learning technology. Educational Technology & Society (2000) Medical apps for smartphones: Lack of evidence undermines quality and safety Evidence Based Medicine (2013) EVIDENCE OF EFFECTIVENESS PAUCITY OF -

Remote Learning Resources: a Guide for Teachers

Remote Learning Resources: A Guide for Teachers Nicole M. Summers-Gabr, Ph.D.; MS Jessica Grim, MPH Amanda Fogleman, MEng Heather Whetsell, MBA Kara Bowlin, BA Sameer Vohra, MD; JD; MA; FAAP July 10, 2020 Department of Population Science and Policy, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine www.siumed.edu/popscipolicy Table of Contents Overview .................................................................................................................. 3 Graph 1: Top 15 Remote Learning Resources .............................................................. 4 Table 1: Remote Learning Resources Overview ........................................................... 5 Detailed Resource List .............................................................................................. 10 www.siumed.edu/popscipolicy OVERVIEW The purpose of this report is to examine which resources were rated most effective by teachers during COVID-19. Online learning resource information is listed to easily identify which grades and subjects the resources serve. This report is designed to serve as an online learning resource clearinghouse to help teachers and school districts identify new or additional remote learning tools to help teachers in the event that remote learning returns in 2020-2021. On March 17, 2020, public schools closed across the state of Illinois in an attempt to slow the spread of COVID-19. As of March 27, 2020, 1.5 billion children worldwide were impacted by school closuresi. With these closures, many schools quickly transitioned to remote learning. While college classes may more easily shift to audio-recorded lectures and online learning platforms like Blackboard, K-12 teachers had to face a new reality in class preparation. Past studies have considered the impact that localized environmental crises had on students’ educationii However, these environmental crises did not have the national reach, duration, and economic impact of COVID-19.