Rhetoric and Civic Belonging: Lynching and the Making of National Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Terrorism Research, Volume 5, Issue 3 (2014)

ISSN: 2049-7040 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Contents Articles 3 Drones, The US And The New Wars In Africa 3 by Philip Attuquayefio The Central Intelligence Agency’s Armed Remotely Piloted Vehicle-Supported Counter-Insurgency Campaign in Pakistan – a Mission Undermined by Unintended Consequences? 14 by Simon Bennett Human Bombing - A Religious Act 31 by Mohammed Ilyas Entering the Black Hole: The Taliban, Terrorism, and Organised Crime 39 by Matthew D. Phillips, Ph.D. and Emily A. Kamen The Theatre of Cruelty: Dehumanization, Objectification & Abu Ghraib 49 by Christiana Spens Book Review 70 Andrew Silke, et al., (edited by Andrew Silke). Prisons, Terrorism and Extremism: Critical Issues in Management, Radicalisation and Reform.Routledge: Oxon UK, 2014. pp. 282. £28.99. ISBN: 978-0-415- 81038-8. 70 reviewed by Robert W. Hand About JTR 74 JTR, Volume 5, Issue 3 – September 2014 Articles Drones, The US And The New Wars In Africa by Philip Attuquayefio This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Introduction ince the early 20th Century, Africa has witnessed varying degrees of subversion from the Mau Mau nationalist campaigners in Kenya in the 1950s to acts by rebel groups in the infamous intrastate wars Sof Sub-Saharan Africa. While the first movement evolved mainly from political acts geared towards the struggle for independence, the latter was mostly evident in attempts to obtain psychological or strategic advantages by combatants in the brutal civil wars of Liberia, Sierra Leone, the African Great Lakes region and a number of such civil war theatres in Africa. -

2007-08 Mgguide-CORRECTED.Qxd

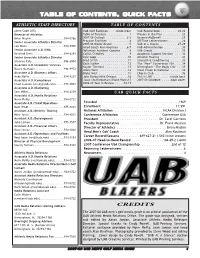

TABLE OF CONTENTS, QUICK FACTS ATHLETIC STAFF DIRECTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS (Area Code 205) UAB Golf Facilities . .inside front UAB Record Book . .20-22 Director of Athletics Table of Contents . .1 Players in the Pros . .22 Brian Mackin ..............................934-0766 2007-08 Outlook . .2-3 Graeme McDowell . .25 Senior Associate Athletics Director Practice Facilities . .4 All-Time Letterwinners . .26 2007-08 Blazer Roster . .5 UAB at a Glance . .27-29 Lee Moon..................................934-1900 Head Coach Alan Kaufman . .6-7 UAB Administration . .30 Senior Associate A.D./SWA Volunteer Assistant Coaches . .8 UAB Greats . .31 Rosalind Ervin ............................934-6283 Cathal O’Malley . .9 Academic Support Services . .32 Senior Associate Athletics Director Kyle Sapp . .10 Athletic Training . .33 Shannon Ealy .............................996-6004 Brad Smith . .11 Strength & Conditioning . .33 Zach Sucher . .12 The “New” Conference USA . .34 Associate A.D./Academic Services Kaylor Timmons . .13 Birmingham - The Magic City . .35 Danez Marrable ..........................996-9972 Adam West . .14 Shoal Creek Invitational . .36 Associate A.D./Business Affairs Blake West . .15 Chip-In Club . .36 Andy Hollis................................934-8221 John Darby/Mike Oimoen . .16 This is UAB . .inside back Associate A.D./Compliance Jason Shufflebotham/Blake Watts17 2007-08 Schedule . .back cover Chad Jackson ([email protected]) .......975-3051 2006-07 Year In Review . .18-19 Associate A.D./Marketing Sam Miller.................................934-1239 UAB QUICK FACTS Associate A.D./Media Relations Norm Reilly ...............................934-0722 Associate A.D./Ticket Operations Founded . .1969 Matt Wildt.................................975-8221 Enrollment . 17,591 Assistant A.D./Athletic Training National Affiliation . NCAA Division I Mike Jones ................................934-6013 Conference Affiliation . -

Exhibiting Racism: the Cultural Politics of Lynching Photography Re-Presentations

EXHIBITING RACISM: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF LYNCHING PHOTOGRAPHY RE-PRESENTATIONS by Erika Damita’jo Molloseau Bachelor of Arts, Western Michigan University, 2001 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented August 8, 2008 by Erika Damita’jo Molloseau It was defended on September 1, 2007 and approved by Cecil Blake, PhD, Department Chair and Associate Professor, Department of Africana Studies Scott Kiesling, PhD, Department Chair and Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics Lester Olson, PhD, Professor, Department of Communication Dissertation Advisor, Ronald Zboray, PhD, Professor and Director of Graduate Study, Department of Communication ii Copyright © by Erika Damita’jo Molloseau 2008 iii EXHIBITING RACISM: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF LYNCHING PHOTOGRAPHY RE-PRESENTATIONS Erika Damita’jo Molloseau, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 Using an interdisciplinary approach and the guiding principles of new historicism, this study explores the discursive and visual representational history of lynching to understand how the practice has persisted as part of the fabric of American culture. Focusing on the “Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America” exhibition at three United States cultural venues I argue that audiences employ discernible meaning making strategies to interpret these lynching photographs and postcards. This examination also features analysis of distinct institutional characteristics of the Andy Warhol Museum, Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site, and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, alongside visual rhetorical analysis of each site’s exhibition contents. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Towards a Theory of Digital Necropolitics Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1059d63h Author Romeo, Francesca Maria Publication Date 2021 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ TOWARDS A THEORY OF DIGITAL NECROPOLITICS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in FILM AND DIGITAL MEDIA by Francesca M. Romeo June 2021 The Dissertation of Francesca M. Romeo is approved: _______________________________________________ Professor Neda Atanasoski, chair _______________________________________________ Professor Shelley Stamp _______________________________________________ Professor Banu Bargu _______________________________________________ Professor Kyle Parry _______________________________________________ Professor Lawrence Andrews ____________________________________________ Quentin Williams Interim Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1.1 Towards a Theory of Digital Necropolitics…………………………………………… ...1 1.2 Digital Necropolitics and Digitally enabled Necroresistance……………………5 1.3 Charting the Digital Revolution, Digital Necropolitics and the Rise of Necroresistance…………………………………………………………………………………………..9 1.4 Digital Necropolitics and the Construction of New Social Imaginaries…….29 1.5 Chapter -

Judicial, Legislative and Economic Approaches to Private Race and Gender Consciousness

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 37 2003 Reflections on ugusta:A Judicial, Legislative and Economic Approaches to Private Race and Gender Consciousness Scott R. Rosner Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Scott R. Rosner, Reflections on Augusta: Judicial, Legislative and Economic Approaches to Private Race and Gender Consciousness, 37 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 135 (2003). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol37/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REFLECTIONS ON AUGUSTA: JUDICIAL, LEGISLATIVE AND ECONOMIC APPROACHES TO PRIVATE RACE AND GENDER CONSCIOUSNESS Scott R. Rosner* In light of the recent controversy surrounding Augusta National Golf Club's exclusionary membership policy, this Article highlights the myriad incentives and disincentives that Augusta and similar clubs havefor reforming such policies. The author acknowledges the economic importance of club membership in many busi- ness communities and addresses the extent to which club members' claims of rights of privacy andfree association are valid. The Article also considers the potential of judicialaction in promoting the adoption of more inclusive membership policy; the state action doctrine and the First Amendment right to freedom of association are discussed as frameworks under which litigants may potentially bring claims against clubs and the author assesses the likelihood of success under each. -

Bitter-Sweet Home: the Pastoral Ideal in African-American Literature, from Douglass to Wright

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2011 Bitter-Sweet Home: The Pastoral Ideal in African-American Literature, from Douglass to Wright Robyn Merideth Preston-McGee University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Preston-McGee, Robyn Merideth, "Bitter-Sweet Home: The Pastoral Ideal in African-American Literature, from Douglass to Wright" (2011). Dissertations. 689. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/689 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi BITTER-SWEET HOME: THE PASTORAL IDEAL IN AFRICAN-AMERICAN LITERATURE, FROM DOUGLASS TO WRIGHT by Robyn Merideth Preston-McGee Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 The University of Southern Mississippi BITTER-SWEET HOME: THE PASTORAL IDEAL IN AFRICAN-AMERICAN LITERATURE, FROM DOUGLASS TO WRIGHT by Robyn Merideth Preston-McGee May 2011 Discussions of the pastoral mode in American literary history frequently omit the complicated relationship between African Americans and the natural world, particularly as it relates to the South. The pastoral, as a sensibility, has long been an important part of the southern identity, for the mythos of the South long depended upon its association with a new “Garden of the World” image, a paradise dependent upon slave labor and a racial hierarchy to sustain it. -

Tung Tried: Agricultural Policy and the Fate of a Gulf South Oilseed Industry, 1902-1969

Automated Template B: Created by James Nail 2011V2.01 Tung tried: agricultural policy and the fate of a Gulf South oilseed industry, 1902-1969 By Whitney Adrienne Snow A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Department of History Mississippi State, Mississippi May 2013 Copyright by Whitney Adrienne Snow 2013 Tung tried: agricultural policy and the fate of a Gulf South oilseed industry, 1902-1969 By Whitney Adrienne Snow Approved: _________________________________ _________________________________ Mark D. Hersey Alison Collis Greene Associate Professor of History Assistant Professor of History (Director of Dissertation) (Committee Member) _________________________________ _________________________________ Stephen C. Brain Alan I Marcus Assistant Professor of History Professor of History (Committee Member) (Committee Member) _________________________________ _________________________________ Sterling Evans Peter C. Messer Committee Participant of History Associate Professor of History (Committee Member) (Graduate Coordinator) _________________________________ R. Gregory Dunaway Professor and Interim Dean College of Arts & Sciences Name: Whitney Adrienne Snow Date of Degree: May 11, 2013 Institution: Mississippi State University Major Field: History Director of Dissertation: Mark D. Hersey Title of Study: Tung tried: agricultural policy and the fate of a Gulf South oilseed industry, 1902-1969 Pages in Study: -

No Women (And Dogs) Allowed: a Comparative Analysis of Discriminating Private Golf Clubs in the United States, Ireland, and England

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Symposium on Regulatory Takings in Land-Use Law: A Comparative Perspective on Compensation Rights January 2007 No Women (and Dogs) Allowed: A Comparative Analysis of Discriminating Private Golf Clubs in the United States, Ireland, and England Eunice Song Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Eunice Song, No Women (and Dogs) Allowed: A Comparative Analysis of Discriminating Private Golf Clubs in the United States, Ireland, and England, 6 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 181 (2007), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol6/iss1/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NO WOMEN (AND DOGS) ALLOWED: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF DISCRIMINATING PRIVATE GOLF CLUBS IN THE UNITED STATES, IRELAND, AND ENGLAND INTRODUCTION In June 2005, Ireland’s High Court overruled a February 2004 landmark decision by district court Judge Mary Collins concerning sexual discrimination of women by private golf clubs in Ireland.1 Initially, Judge Collins ruled that the Portmarnock Golf Club,2 one -

Reopening the Emmett Till Case: Lessons and Challenges for Critical Race Practice

REOPENING THE EMMETT TILL CASE: LESSONS AND CHALLENGES FOR CRITICAL RACE PRACTICE MargaretM. Russell* INTRODUCTION Oh, what sorrow, Pity, pain, That tears and blood Should mix like rain In Mississippi! And terror, fetid hot, Yet clammy cold Remain.1 On May 10, 2004, the United States Department of Justice and the Mississippi District Attorney's Office for the Fourth District * Professor of Law, Santa Clara University School 'of Law. A.B., Princeton University; J.D., Stanford Law School; J.S.M., Stanford Law School. The author extends deep thanks to the following people for support ard assistance: symposium organizer Sheila Foster; symposium co-panelists Anthony Aifieri, Sherrilyn Ifill, and Terry Smith; research assistants Rowena Joseph and Ram Fletcher (both of the Santa Clara University School of Law, Class of 2005); research assistant Daniel Lam (Georgetown University Law Center, Class of 2006); Lee Halterman; Kimiko Russell- Halterman; Donald Polden; and Stephanie Wildman. The following entities deserve special praise for sponsoring this symposium: the FordhamLaw Review and Fordham University School of Law's Louis Stein Center for Law & Ethics. Finally, I am grateful to the Santa Clara University School of Law, particularly the Center for Social Justice & Public Service, for supporting the research project that produced this Essay. The author dedicates this Essay to the memory of Herman Levy, colleague extraordinaire. 1. Langston Hughes, Mississippi-1955 (1955), reprinted in The Lynching of Enumett Till: A Documentary Narrative 294 (Christopher Metress ed., 2002) [hereinafter The Lynching of Emmett Till]; see also Christopher Metress, Langston Hughes's "Mississippi-1955": A Note on Revisions and an Appeal for Reconsideration, 37 Afr.-Am. -

Lynched for Drinking from a White Man's Well

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse this site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.× (More Information) Back to article page Back to article page Lynched for Drinking from a White Man’s Well Thomas Laqueur This April, the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit law firm in Montgomery, Alabama, opened a new museum and a memorial in the city, with the intention, as the Montgomery Advertiser put it, of encouraging people to remember ‘the sordid history of slavery and lynching and try to reconcile the horrors of our past’. The Legacy Museum documents the history of slavery, while the National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates the black victims of lynching in the American South between 1877 and 1950. For almost two decades the EJI and its executive director, Bryan Stevenson, have been fighting against the racial inequities of the American criminal justice system, and their legal trench warfare has met with considerable success in the Supreme Court. This legal work continues. But in 2012 the organisation decided to devote resources to a new strategy, hoping to change the cultural narratives that sustain the injustices it had been fighting. In 2013 it published a report called Slavery in America: The Montgomery Slave Trade, followed two years later by the first of three reports under the title Lynching in America, which between them detailed eight hundred cases that had never been documented before. The United States sometimes seems to be committed to amnesia, to forgetting its great national sin of chattel slavery and the violence, repression, endless injustices and humiliations that have sustained racial hierarchies since emancipation. -

History of Sport, Government and Golf in New Zealand

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. THE POLITICS OF SPORT FUNDING: AN ANALYSIS OF DISCOURSES IN NEW ZEALAND GOLF A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS at The University of Waikato by TIDAVADEE TONGDETHSRI 2015 i Abstract In recent decades, the level of government intervention in sport has increased, involving greater resource allocations to community sport development, high performance sport and business capability initiatives. Within this context, sports organisations have faced increasing expectations around financial accountability and the need to provide professional governance and management. Increasing government intervention in sport has, however, not been matched by a growth in research, particularly into the way government involvement both reflects and contributes to changing understandings of the nature of sport and related changes to sports organisation that affect people’s opportunities to participate. -

Lynching and Postmemory in Lashawnda Crowe Storm's "Her Name Was Laura Nelson"

TO BE A WITNESS: LYNCHING AND POSTMEMORY IN LASHAWNDA CROWE STORM'S "HER NAME WAS LAURA NELSON" Viola Ratcliffe A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2015 Committee: Allison Terry-Fritsch, Advisor Rebecca L. Skinner Greene ii ABSTRACT Allison Terry-Fritsch, Advisor The literal reframing of the lynching postcard The Lynching of Laura Nelson within the medium of quilting allows for a visual re-contextualization of this image’s history. In LaShawnda Crowe Storm’s Quilt I: Her Name Was Laura Nelson the confrontation between viewers and the lynched body of an African American woman addresses an often neglected phenomenon, the lynching of black women in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th century. The literal reframing of the lynching postcard The Lynching of Laura Nelson within the medium of quilting allows for a visual re-contextualization of this image’s history. In the act of quilting Crowe Storm has removed this image from its original intention, a form of propaganda used to fuel racist ideology, and has now placed it within a context of feminism, activism, and communal art making. The selection of the medium of quilting in this work was intentional. In quilting LaShawnda Crowe Storm situates the work, and its attendant imagery, within a dialogue regarding female identity, the construction of community and the history of racial violence in the United States. As a community leader and activist in the city of Indianapolis, Indiana, LaShawnda Crowe Storm developed The Lynch Quilts Project as a means to bring people from across the country together to have an honest dialogue about the legacy of lynching and racial violence in the United States.