Watch Project – Kanggime Extension Baeline and Midterm Survey Results 1999 – 2000 Page 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

Kosipe Revisited

Peat in the mountains of New Guinea G.S. Hope Department of Archaeology and Natural History, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY Peatlands are common in montane areas above 1,000 m in New Guinea and become extensive above 3,000 m in the subalpine zone. In the montane mires, swamp forests and grass or sedge fens predominate on swampy valley bottoms. These mires may be 4–8 m in depth and up to 30,000 years in age. In Papua New Guinea (PNG) there is about 2,250 km2 of montane peatland, and Papua Province (the Indonesian western half of the island) probably contains much more. Above 3,000 m, peat soils form under blanket bog on slopes as well as on valley floors. Vegetation types include cushion bog, grass bog and sedge fen. Typical peat depths are 0.5‒1 m on slopes, but valley floors and hollows contain up to 10 m of peat. The estimated total extent of mountain peatland is 14,800 km2 with 5,965 km2 in PNG and about 8,800 km2 in Papua Province. The stratigraphy, age structure and vegetation histories of 45 peatland or organic limnic sites above 750 m have been investigated since 1965. These record major vegetation shifts at 28,000, 17,000‒14,000 and 9,000 years ago and a variable history of human disturbance from 14,000 years ago with extensive clearance by the mid- Holocene at some sites. While montane peatlands were important agricultural centres in the Holocene, the introduction of new dryland crops has resulted in the abandonment of some peatlands in the last few centuries. -

Indonesia (Republic Of)

Indonesia (Republic of) Last updated: 31-01-2004 Location and area Indonesia is an island republic and largest nation of South East Asia, stretching across some 5,000 km and with a north-south spread of about 2,000 km. The republic shares the island of Borneo with Malaysia and Brunei Darussalam; Indonesian Borneo, equivalent to about 75 per cent of the island, is called Kalimantan. The western half of New Guinea is the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya (formerly West Irian); the eastern half is part of Papua New Guinea. The marine frontiers of Indonesia include the South China Sea, the Celebes Sea, and the Pacific Ocean to the north, and the Indian Ocean to the south and west. Indonesia has a land area of 1,904,443 km2. (Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia 2002). According to Geoanalytics (www.geoanalytics.com/bims/bims.htm) the land area of Indonesia comprises 1,919,663 km2. Topography Indonesia comprises 13,677 islands on both sides of the equator, 6,000 of which are inhabited. Kalimantan and Irian Jaya, together with Sumatra (also called Sumatera), Java (Jawa), and Celebes (Sulawesi) are the largest islands and, together with the insular provinces of Kalimantan and Irian Jaya, account for about 95 per cent of its land area. The smaller islands, including Madura, Timor, Lombok, Sumbawa, Flores, and Bali predominantly form part of island groups. The Moluccas (Maluku) and the Lesser Sunda Islands (Nusatenggara) are the largest island groups. The Java, Flores, and Banda seas divide the major islands of Indonesia into two unequal strings. The comparatively long, narrow islands of Sumatra, Java, Timor (in the Nusatenggara group), and others lie to the south; Borneo, Celebes, the Moluccas, and New Guinea lie to the north. -

"Christian Life and the Living Dead," Melanesian Journal of Theology 13.2

Melanesian Journal of Theology 13-2 (1997) CHRISTIAN LIFE AND THE LIVING DEAD Russell Thorp Russell Thorp is a New Zealander, who was born in Papua New Guinea. He holds a Bachelor of Ministries from the Bible College of New Zealand. He is currently teaching at the Christian Leaders’ Training College. The following article was written as part of a Master’s degree program. Question: Can primal funeral rites be used in some way to convey a Christian message? To explore this issue we will compare the funeral rites of a Papuan cultural group with those of an African group.1 I will first summarise the African funeral ceremony, as Don Brown relates it in his article. Then I will describe and analyse the funeral ritual of the “Dugum Dani”,2 a Papuan culture in the Highlands of Western Papua New Guinea.3 Once we have a picture of both rituals, we will then use the work of Arnold Van Gennep4 and Ronald Grimes5 to analyse the Dugum Dani ritual. By then, we will be able to draw on our findings, to work out if some aspects of the Dugum Dani funeral rites can be used in conveying a Christian message. 1 Don Brown, “The African Funeral Ceremony: Stumbling Block or Redemptive Analogy?”, in International Journal for Frontier Missions 2-3 (July 1985), p. 255. 2 It has since come to the attention of the author of this article that the name of the tribal group is now recognised as the Dugum Lani people. 3 Karl G. Heider, The Dugum Dani, New York NY: Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, 1970. -

Welcome to the Heaven of Specialty Coffee

Coffee Quotes INDONESIA “ I have measured out my life with coffee spoons. ” (T. S. Eliot) “ If I asked for a cup of coffee, EDITION someone would search for the double meaning. ” (Mae West) “ To me, the smell of fresh-made coffee is one Trade•Tourism•Investment FIRST of the greatest inventions. ” (Hugh Jackman) “ The ability to deal with people is as purchasable a commodity as sugar or coffee and I will pay more for that ability than for any other under the sun. ” Welcome to The Heaven (John D. Rockefeller) “ Coffee is a language in itself. ” of Specialty Coffee (Jackie Chan) “ I like cappuccino, actually. But even a bad cup of coffee is better than no coffee at all. ” (David Lynch) “ If it wasn't for the coffee, I'd have no identifiable personality whatsover. “ (David Letterman) :” Good communication is as stimulating as black coffee, and just as hard. ” (Anne Spencer) “ I would rather suffer with coffee than be senseless. “ (Napoleon Bonaparte) “ Coffee, the favourite drink of civilize world. ” (Thomas Jefferson) “ What on earth could be more luxurious than a sofa, a book and a cup of coffee? “ (Anthony Troloppe) “Coffee is far more than a beverage. It is an invitation to life, (Foto: web/edit) disguised as a cup of warm liquid. It’s a trumpet wakeup call or a gentle rousing hand on your shoulder… Coffee is an experience, an offer, a rite of passage, a good excuse to get together. ” (Nichole Johnson) “ A guy’s gotta live, you know, gotta make his way and find his Exotic & Unique Indonesian Coffee meaning in life and love, and to do that he needs coffee, he needs coffee and coffee and coffee. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

Boor En Spade Xi

MEDEDELINGEN VAN DE STICHTING VOOR BODEMKARTERING BOOR EN SPADE XI VERSPREIDE BIJDRAGEN TOT DE KENNIS VAN DE BODEM VAN NEDERLAND AUGER AND SPADE XI STICHTING VOOR BODEMKARTERING, WAGENINGEN DIRECTEUR: DR. IR. F. W. G. PIJLS Soil Survey Institute, Wageningen, Holland Director: Dr. Ir. F. W. G. Pijls 1961 H. VEENMAN & ZONEN N.V.-WAGENINGEN CONTENTS Page Introductory ix 1. Osse, M.J. M., In memoriam Dr. Ir. W. N. Myers 1 2. Osse, M.J. M. et al., The Netherlands Soil Survey Institute. Tasks, activities and organization 4 3. Steur, G. G. L. et al., Methods of soil surveying in use at the Nether lands Soil Survey Institute 59 4. Reynders, J. J., Soil Survey in Netherlands New Guinea .... 78 5. Schroo, H., Some pedological data concerning soils in the Baliem Valley, Netherlands New Guinea 84 6. Reynders, J. J., The landscape in the Maro and Koembe river district (Merauke, Southern Netherlands New Guinea) 104 7. Maarleveld, G. C. and J. S. van der Merwe, Aerial survey in the vicinity of Potchefstroom, Transvaal 120 8. Oosten, M. F. van, Soils and Gilgai microrelief in a central African river plain in the light of the quaterny climatic changes .... 126 9. Marel, H. W. van der, Properties of rocks in civil and rural engi neering 149 10. Meer, K. van der, Soil conditions in the Khulna District (East Pa kistan) 170 INHOUD De pagina-nummers verwijzen naar de Nederlandse samenvatting Blz. Ter inleiding ix 1. Osse, M. J. M., In memoriam Dr. Ir. W. N. Myers 1 2. Osse, M. J. M. -

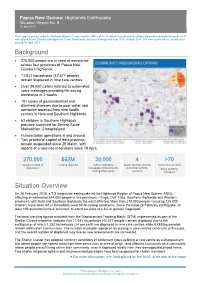

Background Situation Overview

Papua New Guinea: Highlands Earthquake Situation Report No. 8 20 April 2018 This report is produced by the National Disaster Centre and the Office of the Resident Coordinator in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by the Disaster Management Team Secretariat, and covers the period from 10 to 16 April 2018. The next report will be issued on or around 26 April 2018. Background • 270,000 people are in need of assistance across four provinces of Papua New Guinea’s highlands. • 11,041 households (42,577 people) remain displaced in nine care centres. • Over 38,000 callers listened to automated voice messages providing life-saving assistance in 2 weeks • 181 cases of gastrointestinal and diarrheal diseases due to poor water and sanitation reported from nine health centres in Hela and Southern Highlands. • 62 children in Southern Highlands province screened for Severe Acute Malnutrition; 2 hospitalized. • Humanitarian operations in and around Tari, provincial capital of Hela province, remain suspended since 28 March, with reports of a new rise in tensions since 19 April. 270,000 $62M 38,000 4 >70 people in need of funding required callers listened to health facilities started metric tons of relief assistance messages containing life- providing nutrition items awaiting saving information services transport Situation Overview On 26 February 2018, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake hit the Highlands Region of Papua New Guinea (PNG), affecting an estimated 544,000 people in five provinces – Enga, Gulf, Hela, Southern Highlands and Western provinces, with Hela and Southern Highlands the most affected. More than 270,000 people, including 125,000 children, have been left in immediate need of life-saving assistance. -

Australasian Journal of Herpetology

Australasian Journal of Herpetology Hoser, R. T. 2020. For the first time ever! An overdue review and reclassification of Australasian Tree Frogs (Amphibia: Anura: Pelodryadidae), including formal descriptions of 12 tribes, 11 subtribes, 34 genera, 26 subgenera, 62 species and 12 subspecies new to science. AJH 44-46:1-192. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) ISSUEISSUE 44,44, PUBLISHEDPUBLISHED 55 JUNEJUNE 20202020 2 Australasian Journal of Herpetology Australasian Journal of Herpetology 44-46:1-192. Published 5 June 2020. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) For the first time ever! An overdue review and reclassification of Australasian Tree Frogs (Amphibia: Anura: Pelodryadidae), including formal descriptions of 12 tribes, 11 subtribes, 34 genera, 26 subgenera, 62 species and 12 subspecies new to science. LSIDURN:LSID:ZOOBANK.ORG:PUB:0A14E077-B8E2-444E-B036-620B311D358D RAYMOND T. HOSER LSIDURN:LSID:ZOOBANK.ORG:AUTHOR:F9D74EB5-CFB5-49A0-8C7C-9F993B8504AE 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 4 November 2019, Accepted 2 June 2020, Published 5 June 2020. ABSTRACT For the past 200 years most, if not all Australian Tree Frogs have been treated as being in a single genus. For many years this was Hyla Laurenti, 1768, before the genus name Litoria Tschudi, 1838 was adopted by Cogger et al. (1983) and has been in general use by most herpetologists since, including Cogger (2014). Tyler and Davies (1978) divided the putative genus Litoria into 37 “species groups” and this type of classification has been used by numerous authors since, including most recently Menzies (2006) for the New Guinea species and Anstis (2014) for the Australian ones. -

Year 2018, Volume-09, Issue-1

Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development EXECUTIVE EDITOR Prof Vidya Surwade Prof Dept of Community Medicine SIMS, Hapur INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD NATIONAL EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD 1. Dr. Abdul Rashid Khan B. Md Jagar Din, (Associate Professor) 5. Prof. Samarendra Mahapatro (Pediatrician) Department of Public Health Medicine, Penang Medical College, Penang, Malaysia Hi-Tech Medical College, Bhubaneswar, Orissa 2. Dr. V Kumar (Consulting Physician) 6. Dr. Abhiruchi Galhotra (Additional Professor) Community and Family Mount View Hospital, Las Vegas, USA Medicine, AII India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur 3. Basheer A. Al-Sum, 7. Prof. Deepti Pruthvi (Pathologist) SS Institute of Medical Sciences & Botany and Microbiology Deptt, College of Science, King Saud University, Research Center, Davangere, Karnataka Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 8. Prof. G S Meena (Director Professor) 4. Dr. Ch Vijay Kumar (Associate Professor) Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi Public Health and Community Medicine, University of Buraimi, Oman 9. Prof. Pradeep Khanna (Community Medicine) 5. Dr. VMC Ramaswamy (Senior Lecturer) Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana Department of Pathology, International Medical University, Bukit Jalil, Kuala Lumpur 10. Dr. Sunil Mehra (Paediatrician & Executive Director) 6. Kartavya J. Vyas (Clinical Researcher) MAMTA Health Institute of Mother & Child, New Delhi Department of Deployment Health Research, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (USA) 11. Dr Shailendra Handu, Associate Professor, Phrma, DM (Pharma, PGI 7. Prof. PK Pokharel (Community Medicine) Chandigarh) BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Nepal 12. Dr. A.C. Dhariwal: Directorate of National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, Dte. DGHS, Ministry of Health Services, Govt. of NATIONAL SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE India, Delhi 1. -

West Papuan Refugees from Irian Jaya in Papua New Guinea

� - ---==� 5G04AV �1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111�11 � 3 4067 01802 378 7 � THE UNIVERSilY OF QUEENSLAND Accepted for the award of MR..�f.� �f .. kl:�.. .................. on .P...l .� ...�. ��.��. .. .. ��� � WEST PAPUAN REFUGEES FROM IRIAN JAVA IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA Susan Sands Submilted as 11 Research Master of Arts Degree at The University of QIU!ensland 1992 i DECLARATION This thesis represents originalsearc re h undertaken for a Master of Arts Degree at the University of Queensland. The interpretations presented are my own and do not represent the view of any other person except where acknowledged in the text ii. Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. David Hyndman, whose concern for the people of the Fourth World encouraged me to continue working on this area of study, and for his suggestion that I undertake fieldwork in the Western Province refugee camps in Papua New Guinea. The University of Queensland supplied funds for airfares between Brisbane, Port Moresby and Kiunga and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees arranged for UN transport in the Western Province. I thank both these institutions for supporting my visit to Papua New Guinea. Over the course of time, officials in both government and non-government institutions change; for this reason I would like to thank the institutions rather than individual persons. Foremost among these are the Department of Provincial Government and the Western Province Provincial Government, the Papua New Guinea Departtnent of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Young Women's Christian Association of Papua New Guinea, the Papua New Guinea Department of Health, the Catholic Church Commission for Justice, Peace and Development, the Montfort Mission (Kiunga and East Awin), the ZOA Medical mission, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Canberra and Port More�by). -

Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia

Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia As the largest Muslim country in the world, Indonesia is marked by an extraordinary diversity of languages, traditions, cultures, and religions. Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia focuses on Dani Christians of West Papua, providing a social and ethnographic history of the most important indigenous population in the troubled province. It presents a captivating overview of the Dani conversion to Christianity, examining the social, religious, and political uses to which they have put their new religion. Farhadian provides the first major study of a highland Papuan group in an urban context, which distinguishes it from the typical highland Melanesian ethnography. Incorporating cultural and structural approaches, the book affords a fascinating look into the complex relationship among Christianity, Islam, nation making, and indigenous traditions. Based on research over many years, Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia offers an abundance of new material on religious and political events in West Papua. The book underlines the heart of Christian–Muslim rivalries, illuminating the fate of religion in late-modern times. Charles E. Farhadian is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Westmont College, Santa Barbara, California. Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series 1 Land Tenure, Conservation and Development in Southeast Asia Peter Eaton 2 The Politics of Indonesia–Malaysia Relations One kin, two nations Joseph Chinyong Liow 3 Governance and Civil Society in Myanmar Education, health and environment Helen James 4 Regionalism in Post-Suharto Indonesia Edited by Maribeth Erb, Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, and Carole Faucher 5 Living with Transition in Laos Market integration in Southeast Asia Jonathan Rigg 6 Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia Charles E.