Building a Cyclic Gauss Gun Tom Welch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US2510669.Pdf

June 6, 1950 C. A. THOMAS 2,510,669 DYNAMOELECTRICMACHINE WITH RESIDUAL FIELD COMPENSATION Filed Sept. 15, 1949 InN/entor : Charles A.Thomas : -2-YHis attorney. 213-4- - Patented June 6, 1950 2,510,669 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,510,669 DYNAMoELECTRIC MACHINE WITH RESD UAL FIELD coMPENSATION Charles A. Thomas, Fort Wayne, Ind., assignor - to General Electric Company, a corporation of New York Application September 15, 1949, Serial No. 115,907 2 Claims. (Cl. 322-79) 2 My invention relates to dynamoelectric ma volves added expense and requires additional chines incorporating means for eliminating field maintenance. excitation which is due to residual magnetism It is, therefore, another object of my inven in the field and, more particularly, to dynamo tion to provide a dynamoelectric machine in electric machines having residual field Com Corporating a residual field compensator which pensating windings and associated non-linear does not require additional Switches or auxiliary impedance elements for rendering said windings contacts, but which is, nevertheless, effective inoperative when not required, without the use during periods of zero field excitation by the of switches. control field Windings and ineffective when the in certain types of dynamoelectric machines, O control windings supply excitation. the presence of the usual residual magnetization My invention, therefore, Consists essentially remaining in the field poles of the machine after of a dynamoelectric machine having a residual field excitation has been removed is undesired magnetization compensator which includes a and troublesone. This is especially true in ar- . compensator field winding connected in the air nature reaction excited dynamoelectric ma 5 nature circuit of the machine and associated chines having compensation for secondary ar non-linear impedance elements to render the nature reaction and commonly known as ampli winding ineffective when normal field excitation dynes. -

High Efficiency Megawatt Motor Conceptual Design

High Efficiency Megawatt Motor Conceptual Design Ralph H. Jansen, Yaritza De Jesus-Arce, Dr. Rodger Dyson, Dr. Andrew Woodworth, Dr. Justin Scheidler, Ryan Edwards, Erik Stalcup, Jarred Wilhite, Dr. Kirsten Duffy, Paul Passe and Sean McCormick NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 44135 Advanced Air Vehicles Program Advanced Transport Technologies Project Motivation • NASA is investing in Electrified Aircraft Propulsion (EAP) research to improve the fuel efficiency, emissions, and noise levels in commercial transport aircraft • The goal is to show that one or more viable EAP concepts exist for narrow- body aircraft and to advance crucial technologies related to those concepts. • Electric Machine technology needs to be advanced to meet aircraft needs. Advanced Air Vehicles Program Advanced Transport Technologies Project 2 Outline • Machine features • Importance of electric machine efficiency for aircraft applications • HEMM design requirements • Machine design • Performance Estimate and Sensitivity • Conclusion Advanced Air Vehicles Program Advanced Transport Technologies Project 3 NASA High Efficiency Megawatt Motor (HEMM) Power / Performance • HEMM is a 1.4MW electric machine with a stretch performance goal of 16 kW/kg (ratio to EM mass) and efficiency of >98% Machine Features • partially superconducting (rotor superconducting, stator normal conductors) • synchronous wound field machine that can operate as a motor or generator • combines a self-cooled, superconducting rotor with a semi- slotless stator Vehicle Level Benefits • -

Pulsed Rotating Machine Power Supplies for Electric Combat Vehicles

Pulsed Rotating Machine Power Supplies for Electric Combat Vehicles W.A. Walls and M. Driga Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712 Abstract than not, these test machines were merely modified gener- ators fitted with damper bars to lower impedance suffi- As technology for hybrid-electric propulsion, electric ciently to allow brief high current pulses needed for the weapons and defensive systems are developed for future experiment at hand. The late 1970's brought continuing electric combat vehicles, pulsed rotating electric machine research in fusion power, renewed interest in electromag- technologies can be adapted and evolved to provide the netic guns and other pulsed power users in the high power, maximum benefit to these new systems. A key advantage of intermittent duty regime. Likewise, flywheels have been rotating machines is the ability to design for combined used to store kinetic energy for many applications over the requirements of energy storage and pulsed power. An addi - years. In some cases (like utility generators providing tran- tional advantage is the ease with which these machines can sient fault ride-through capability), the functions of energy be optimized to service multiple loads. storage and power generation have been combined. Continuous duty alternators can be optimized to provide Development of specialized machines that were optimized prime power energy conversion from the vehicle engine. for this type of pulsed duty was needed. In 1977, the laser This paper, however, will focus on pulsed machines that are fusion community began looking for an alternative power best suited for intermittent and pulsed loads requiring source to capacitor banks for driving laser flashlamps. -

Modeling, Analogue and Tests of an Electric Machine

MODELING, ANALOGUE AND TESTS OF AN ELECTRIC MACHINE VOLTAGE CONTROL SYSTEM 'by GRAHAM E.' DAWSON ( j B.A.Sc, University of British. Columbia, 1963. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS, FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF APPLIED SCIENCE. in the Department of Electrical Engineering We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard Members of the Committee Head of the Department .»»«... Members of the Department of Electrical Engineering THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely.avai1able for reference and study. I further agree that permission for ex• tensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives.. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for finan• cial gain shall not be allowed without my.written permission. Department of Electrical Engineering The University of British Columbia Vancou ve r.,8, Canada Date 7. MM ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the modeling, analogue and tests of an interconnected four electric machine voltage control system. Many analogue studies of electric machines have been done but most are concerned with the development of analogue techniques and only a few give substantiation of the validity of the analogue models through comparison of results from analogue studies and from real machine tests. Chapter 2 describes the procedure and the system under study. Chapter 3 describes the methods used for the determination of the electrical and mechanical system parameters. -

Power Processing, Part 1. Electric Machinery Analysis

DOCONEIT MORE BD 179 391 SE 029 295,. a 'AUTHOR Hamilton, Howard B. :TITLE Power Processing, Part 1.Electic Machinery Analyiis. ) INSTITUTION Pittsburgh Onii., Pa. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washingtcn, PUB DATE 70 GRANT NSF-GY-4138 NOTE 4913.; For related documents, see SE 029 296-298 n EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 PusiPostage. DESCRIPTORS *College Science; Ciirriculum Develoiment; ElectricityrFlectrOmechanical lechnology: Electronics; *Fagineering.Education; Higher Education;,Instructional'Materials; *Science Courses; Science Curiiculum:.*Science Education; *Science Materials; SCientific Concepts ABSTRACT A This publication was developed as aportion of a two-semester sequence commeicing ateither the sixth cr'seventh term of,the undergraduate program inelectrical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh. The materials of thetwo courses, produced by a ional Science Foundation grant, are concernedwith power convrs systems comprising power electronicdevices, electrouthchanical energy converters, and associated,logic Configurations necessary to cause the system to behave in a prescribed fashion. The emphisis in this portionof the two course sequence (Part 1)is on electric machinery analysis. lechnigues app;icable'to electric machines under dynamicconditions are anallzed. This publication consists of sevenchapters which cW-al with: (1) basic principles: (2) elementary concept of torqueand geherated voltage; (3)tile generalized machine;(4i direct current (7) macrimes; (5) cross field machines;(6),synchronous machines; and polyphase -

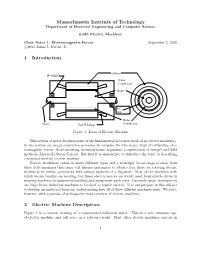

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1 Introduction 2 Electric Machine

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 6.685 Electric Machines Class Notes 1: Electromagnetic Forces September 5, 2005 c 2003 James L. Kirtley Jr. 1 Introduction Stator Bearings Stator Conductors Rotor Air Gap Rotor Shaft End Windings Conductors Figure 1: Form of Electric Machine This section of notes discusses some of the fundamental processes involved in electric machinery. In the section on energy conversion processes we examine the two major ways of estimating elec- tromagnetic forces: those involving thermodynamic arguments (conservation of energy) and field methods (Maxwell’s Stress Tensor). But first it is appropriate to introduce the topic by describing a notional rotating electric machine. Electric machinery comes in many different types and a strikingly broad range of sizes, from those little machines that cause cell ’phones and pagers to vibrate (yes, those are rotating electric machines) to turbine generators with ratings upwards of a Gigawatt. Most of the machines with which we are familiar are rotating, but linear electric motors are widely used, from shuttle drives in weaving machines to equipment handling and amusement park rides. Currently under development are large linear induction machines to be used to launch aircraft. It is our purpose in this subject to develop an analytical basis for understanding how all of these different machines work. We start, however, with a picture of perhaps the most common of electric machines. 2 Electric Machine Description: Figure 1 is a cartoon drawing of a conventional induction motor. This is a very common type of electric machine and will serve as a reference point. -

Evaluating the Effects of Electric and Magnetic Loading on the Performance of Single and Double Rotor Axial Flux PM Machines

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Power and Energy Institute of Kentucky Faculty Publications Power and Energy Institute of Kentucky 4-1-2020 Evaluating the Effects of Electric and Magnetic Loading on the Performance of Single and Double Rotor Axial Flux PM Machines Narges Taran University of Kentucky, [email protected] Greg Heins Regal Beloit Corporation, Australia Vandana Rallabandi University of Kentucky, [email protected] Dean Patterson Regal Beloit Corporation, Australia Dan M. Ionel University of Kentucky, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/peik_facpub Part of the Electromagnetics and Photonics Commons, and the Power and Energy Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Taran, Narges; Heins, Greg; Rallabandi, Vandana; Patterson, Dean; and Ionel, Dan M., "Evaluating the Effects of Electric and Magnetic Loading on the Performance of Single and Double Rotor Axial Flux PM Machines" (2020). Power and Energy Institute of Kentucky Faculty Publications. 5. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/peik_facpub/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Power and Energy Institute of Kentucky at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Power and Energy Institute of Kentucky Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evaluating the Effects of Electric and Magnetic Loading on the Performance of Single and Double Rotor Axial Flux PM Machines Digital Object Identifier (DOI) https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2020.2983632 Notes/Citation Information Published in IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications. -

A Comparitve Study Between Vector Control and Direct Torque Control of Induction Motor Using Matlab Simulink

A COMPARITVE STUDY BETWEEN VECTOR CONTROL AND DIRECT TORQUE CONTROL OF INDUCTION MOTOR USING MATLAB SIMULINK Submitted by Fathalla Eldali Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fall 2012 1 WHEN HAVE I BEEN INTERESTED IN MOTOR DRIVE AND MATLAB? BSC Senior Design LIM + PLC MATLAB/Simulink as A Modeling TOOL 2 THESIS OUTLINES Introduction Induction Motor Principles Induction Motor Modeling Electric Motor Drives Vector Control of Induction Motor Direct Torque Control Theoretical Comparison Vector Control and Direct Torque Control Simulation Results Simulation Results in the normal operation case The effect of Voltage sags and short interruption on driven induction motors The characteristics of the voltage sag and short interruption 3 Conclusion & Future Work INTRODUCTION Motors are needed Un driven Motors and power consumption Power Electronics, DSP revolution help Rectifiers Inverters Sensors Control Systems Theories 4 OLD STUDIES & MOTIVATION Many studies have been done about FOC & DTC individually Few studies were published as a comparison studies as [17-19] Voltage Sag & Short Interruption faults were not considered in the comparison 5 INDUCTION MOTOR PRINCIPLES Nikola Tesla first AC motors 1888 AC motors -Induction Motors -Permanent Magnet Motors Why are Induction Motors are mostly used ? Supplied through stator only Easy to manufacture and maintain Cheap 6 INDUCTION MOTOR CONSTRUCTION Stator : laminated sheet steel (eddy current loses reduction) attached to an iron frame stator consists of mechanical slots insulated copper conductors are buried inside the slots and then Y or Delta connected to the source. 7 Two Types of Rotor A-wound rotor: -Three electrical phases just as the stator does and they (coils) are connected wye or delta. -

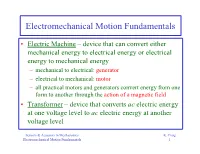

Electromechanical Motion Fundamentals

Electromechanical Motion Fundamentals • Electric Machine – device that can convert either mechanical energy to electrical energy or electrical energy to mechanical energy – mechanical to electrical: generator – electrical to mechanical: motor – all practical motors and generators convert energy from one form to another through the action of a magnetic field • Transformer – device that converts ac electric energy at one voltage level to ac electric energy at another voltage level Sensors & Actuators in Mechatronics K. Craig Electromechanical Motion Fundamentals 1 – It operates on the same principles as generators and motors, i.e., it depends on the action of a magnetic field to accomplish the change in voltage level • Motors, Generators, and Transformers are ubiquitous in modern daily life. Why? – Electric power is: • Clean • Efficient • Easy to transmit over long distances • Easy to control • Environmental benefits Sensors & Actuators in Mechatronics K. Craig Electromechanical Motion Fundamentals 2 • Purpose of this Study – provide basic knowledge of electromechanical motion devices for mechatronic engineers – focus on electromechanical rotational devices commonly used in low-power mechatronic systems • permanent magnet dc motor • brushless dc motor • stepper motor • Topics Covered: – Magnetic and Magnetically-Coupled Circuits – Principles of Electromechanical Energy Conversion Sensors & Actuators in Mechatronics K. Craig Electromechanical Motion Fundamentals 3 References • Electromechanical Motion Devices, P. Krause and O. Wasynczuk, McGraw Hill, 1989. • Electromechanical Dynamics, H. Woodson and J. Melcher, Wiley, 1968. • Electric Machinery Fundamentals, 3rd Edition, S. Chapman, McGraw Hill, 1999. • Driving Force, The Natural Magic of Magnets, J. Livingston, Harvard University Press, 1996. • Applied Electromagnetics, M. Plonus, McGraw Hill, 1978. • Electromechanics and Electric Machines, S. Nasar and L. Unnewehr, Wiley, 1979. -

Switched Reluctance Generators

Switched Reluctance Generators In contrast to well-known conventional generators Switched Reluctance Generator (SRG) have “toothed” stator and rotor, and have neither windings nor permanent magnets in the rotor. For their operation the excitation unit which is controlled in accordance with the rotor angle position is nec- essary. During the operation, active stator poles (i.e., those with winding coils through which the current flows) repel the nearest rotor poles. When the poles are repelled enough, the phase current via diodes is charging DC link capacitor. The excitation current is changed to the next phase by means of the power electronic switches depending of voltage of the DC link capacitor. This way the machine generates the power and keeps DC voltage stable. The unique operation results in unique advantages of the SRG. Absence of magnets and a pas- sive rotor simplify construction and lower the cost of manufacturing. Rotor does not dissipate heat to speak of and in fact can be used to cool the stator, also making the machine less sensitive to high temperatures. Ease of cooling in turn simplifies the task of making construction hermetic. Magnets in conventional electric machines lose their strength when heated or with time, but SRG has no such problem. Passive rotor reduces overall losses in copper winding because it does not have any. The power/weight and torque/weight ratios are higher than those of conventional machines. Since phases of an SRG are independent, the machine is very tolerant to open-coil fault (in the windings) and faults in the power converter. The above features make SRG the most cost effective, the most fault tolerant and the most repairable electric machine in existence. -

Electrical Engineering Dictionary

ratio of the power per unit solid angle scat- tered in a specific direction of the power unit area in a plane wave incident on the scatterer R from a specified direction. RADHAZ radiation hazards to personnel as defined in ANSI/C95.1-1991 IEEE Stan- RS commonly used symbol for source dard Safety Levels with Respect to Human impedance. Exposure to Radio Frequency Electromag- netic Fields, 3 kHz to 300 GHz. RT commonly used symbol for transfor- mation ratio. radial basis function network a fully R-ALOHA See reservation ALOHA. connected feedforward network with a sin- gle hidden layer of neurons each of which RL Typical symbol for load resistance. computes a nonlinear decreasing function of the distance between its received input and Rabi frequency the characteristic cou- a “center point.” This function is generally pling strength between a near-resonant elec- bell-shaped and has a different center point tromagnetic field and two states of a quan- for each neuron. The center points and the tum mechanical system. For example, the widths of the bell shapes are learned from Rabi frequency of an electric dipole allowed training data. The input weights usually have transition is equal to µE/hbar, where µ is the fixed values and may be prescribed on the electric dipole moment and E is the maxi- basis of prior knowledge. The outputs have mum electric field amplitude. In a strongly linear characteristics, and their weights are driven 2-level system, the Rabi frequency is computed during training. equal to the rate at which population oscil- lates between the ground and excited states. -

Modeling and Control of Dual Mechanical Port Electric Machine

MODELING AND CONTROL OF DUAL MECHANICAL PORT ELECTRIC MACHINE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Haiwei Cai Graduate Program in Electrical and Computer Science The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Longya Xu, Advisor Dr. Jin Wang, Dr. Mahesh Illindala Copyright by Haiwei Cai 2015 Abstract The Dual Mechanical Port (DMP) electric machine has two rotors that can be controlled to rotate in different speeds and directions. Compared with conventional electric machines with only one rotor, the DMP machine provides higher torque density and much better control flexibility. However, the DMP machine also has relatively complex structure, which bring challenges to the modeling and control of the machine. The existing model and control algorithms for single rotor electric machines cannot be applied to the DMP machine directly. In this work, the application of DMP machine on hybrid electric vehicle will be used as an example to explain the electromagnetic characteristics and functionality of the DMP machine. The model and the control algorithms for two different DMP machines are investigated. The first DMP machine uses two layers of Permanent Magnets in the outer rotor; it is called the PMDMP machine. The second DMP machine uses single layer of Squirrel Cage in the outer rotor; it is called the SCDMP machine. The study on modeling and control for the SCDMP machine is the major contribution of this work. The PMDMP machine stands out for its high torque density and high efficiency when compared with other DMP machines.