Electromechanical Motion Fundamentals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

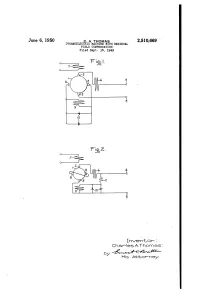

US2510669.Pdf

June 6, 1950 C. A. THOMAS 2,510,669 DYNAMOELECTRICMACHINE WITH RESIDUAL FIELD COMPENSATION Filed Sept. 15, 1949 InN/entor : Charles A.Thomas : -2-YHis attorney. 213-4- - Patented June 6, 1950 2,510,669 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,510,669 DYNAMoELECTRIC MACHINE WITH RESD UAL FIELD coMPENSATION Charles A. Thomas, Fort Wayne, Ind., assignor - to General Electric Company, a corporation of New York Application September 15, 1949, Serial No. 115,907 2 Claims. (Cl. 322-79) 2 My invention relates to dynamoelectric ma volves added expense and requires additional chines incorporating means for eliminating field maintenance. excitation which is due to residual magnetism It is, therefore, another object of my inven in the field and, more particularly, to dynamo tion to provide a dynamoelectric machine in electric machines having residual field Com Corporating a residual field compensator which pensating windings and associated non-linear does not require additional Switches or auxiliary impedance elements for rendering said windings contacts, but which is, nevertheless, effective inoperative when not required, without the use during periods of zero field excitation by the of switches. control field Windings and ineffective when the in certain types of dynamoelectric machines, O control windings supply excitation. the presence of the usual residual magnetization My invention, therefore, Consists essentially remaining in the field poles of the machine after of a dynamoelectric machine having a residual field excitation has been removed is undesired magnetization compensator which includes a and troublesone. This is especially true in ar- . compensator field winding connected in the air nature reaction excited dynamoelectric ma 5 nature circuit of the machine and associated chines having compensation for secondary ar non-linear impedance elements to render the nature reaction and commonly known as ampli winding ineffective when normal field excitation dynes. -

Controlling Phonons and Photons at the Wavelength-Scale: Silicon Photonics Meets Silicon Phononics

1 Controlling phonons and photons at the wavelength-scale: silicon photonics meets silicon phononics AMIR H. SAFAVI-NAEINI1,D RIES VAN THOURHOUT2,R OEL BAETS2, AND RAPHAËL VAN LAER1,2 1Department of Applied Physics and Ginzton Laboratory, Stanford University, USA 2Photonics Research Group (INTEC), Department of Information Technology, Ghent University–imec, Belgium .Center for Nano- and Biophotonics, Ghent University, Belgium Compiled October 9, 2018 Radio-frequency communication systems have long used bulk- and surface-acoustic-wave de- vices supporting ultrasonic mechanical waves to manipulate and sense signals. These devices have greatly improved our ability to process microwaves by interfacing them to orders-of- magnitude slower and lower loss mechanical fields. In parallel, long-distance communications have been dominated by low-loss infrared optical photons. As electrical signal processing and transmission approaches physical limits imposed by energy dissipation, optical links are now being actively considered for mobile and cloud technologies. Thus there is a strong driver for wavelength-scale mechanical wave or “phononic” circuitry fabricated by scalable semiconduc- tor processes. With the advent of these circuits, new micro- and nanostructures that combine electrical, optical and mechanical elements have emerged. In these devices, such as optomechan- ical waveguides and resonators, optical photons and gigahertz phonons are ideally matched to one another as both have wavelengths on the order of micrometers. The development of phononic circuits has thus emerged as a vibrant field of research pursued for optical signal pro- cessing and sensing applications as well as emerging quantum technologies. In this review, we discuss the key physics and figures of merit underpinning this field. -

Electromagnetism What Is the Effect of the Number of Windings of Wire on the Strength of an Electromagnet?

TEACHER’S GUIDE Electromagnetism What is the effect of the number of windings of wire on the strength of an electromagnet? GRADES 6–8 Physical Science INQUIRY-BASED Science Electromagnetism Physical Grade Level/ 6–8/Physical Science Content Lesson Summary In this lesson students learn how to make an electromagnet out of a battery, nail, and wire. The students explore and then explain how the number of turns of wire affects the strength of an electromagnet. Estimated Time 2, 45-minute class periods Materials D cell batteries, common nails (20D), speaker wire (18 gauge), compass, package of wire brad nails (1.0 mm x 12.7 mm or similar size), Investigation Plan, journal Secondary How Stuff Works: How Electromagnets Work Resources Jefferson Lab: What is an electromagnet? YouTube: Electromagnet - Explained YouTube: Electromagnets - How can electricity create a magnet? NGSS Connection MS-PS2-3 Ask questions about data to determine the factors that affect the strength of electric and magnetic forces. Learning Objectives • Students will frame a hypothesis to predict the strength of an electromagnet due to changes in the number of windings. • Students will collect and analyze data to determine how the number of windings affects the strength of an electromagnet. What is the effect of the number of windings of wire on the strength of an electromagnet? Electromagnetism is one of the four fundamental forces of the universe that we rely on in many ways throughout our day. Most home appliances contain electromagnets that power motors. Particle accelerators, like CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, use electromagnets to control the speed and direction of these speedy particles. -

Electromagnetism

EINE INITIATIVE DER UNIVERSITÄT BASEL UND DES KANTONS AARGAU Swiss Nanoscience Institute Electromagnetism Electricity and magnetism are two aspects of the same phenomenon: electromagnetism. A moving electric charge (in other words, an electric current) generates a magnetic field. Every electromagnet consists of a coil, which is nothing more than a tightly wound wire. Many electromagnets also have an iron core to make the magnetic field stronger. The more times the wire is wound around the coil, the stronger the magnetic field produced by the same current. Demonstration: Using electric current to create a magnetic field What you’ll need • a large sheet of paper on which to conduct the experiment • a sheet of stiff card or plexiglass • two batteries connected in series • a coil of copper wire • iron filings • crocodile clips (optional) • a small piece of iron (e.g. a screw) to place inside the coil (iron core) Instructions 1. Position the coil so that you can easily access the two ends of the wire and connect them to the battery. I used crocodile clips to attach them to the battery contacts, but you could also use wooden clothes pegs or electrical tape. 2. Connect the two batteries in series (+ - + - ). 3. Place the plexiglass or card over the coil. 4. When the electrical circuit is closed, slowly scatter the iron filings on top. What happens? The iron filings arrange themselves along the magnetic field lines. If you look closely, you can make out a pattern. Turn a screw into an electromagnet What you’ll need • a long iron screw or nail • two pieces of insulated copper wire measuring 15 and 30 cm • two three-pronged thumb tacks • a metal paperclip • a small wooden board • pins or paperclips • a 4.5 V battery Instructions Switch 1. -

High Efficiency Megawatt Motor Conceptual Design

High Efficiency Megawatt Motor Conceptual Design Ralph H. Jansen, Yaritza De Jesus-Arce, Dr. Rodger Dyson, Dr. Andrew Woodworth, Dr. Justin Scheidler, Ryan Edwards, Erik Stalcup, Jarred Wilhite, Dr. Kirsten Duffy, Paul Passe and Sean McCormick NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio, 44135 Advanced Air Vehicles Program Advanced Transport Technologies Project Motivation • NASA is investing in Electrified Aircraft Propulsion (EAP) research to improve the fuel efficiency, emissions, and noise levels in commercial transport aircraft • The goal is to show that one or more viable EAP concepts exist for narrow- body aircraft and to advance crucial technologies related to those concepts. • Electric Machine technology needs to be advanced to meet aircraft needs. Advanced Air Vehicles Program Advanced Transport Technologies Project 2 Outline • Machine features • Importance of electric machine efficiency for aircraft applications • HEMM design requirements • Machine design • Performance Estimate and Sensitivity • Conclusion Advanced Air Vehicles Program Advanced Transport Technologies Project 3 NASA High Efficiency Megawatt Motor (HEMM) Power / Performance • HEMM is a 1.4MW electric machine with a stretch performance goal of 16 kW/kg (ratio to EM mass) and efficiency of >98% Machine Features • partially superconducting (rotor superconducting, stator normal conductors) • synchronous wound field machine that can operate as a motor or generator • combines a self-cooled, superconducting rotor with a semi- slotless stator Vehicle Level Benefits • -

Pulsed Rotating Machine Power Supplies for Electric Combat Vehicles

Pulsed Rotating Machine Power Supplies for Electric Combat Vehicles W.A. Walls and M. Driga Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712 Abstract than not, these test machines were merely modified gener- ators fitted with damper bars to lower impedance suffi- As technology for hybrid-electric propulsion, electric ciently to allow brief high current pulses needed for the weapons and defensive systems are developed for future experiment at hand. The late 1970's brought continuing electric combat vehicles, pulsed rotating electric machine research in fusion power, renewed interest in electromag- technologies can be adapted and evolved to provide the netic guns and other pulsed power users in the high power, maximum benefit to these new systems. A key advantage of intermittent duty regime. Likewise, flywheels have been rotating machines is the ability to design for combined used to store kinetic energy for many applications over the requirements of energy storage and pulsed power. An addi - years. In some cases (like utility generators providing tran- tional advantage is the ease with which these machines can sient fault ride-through capability), the functions of energy be optimized to service multiple loads. storage and power generation have been combined. Continuous duty alternators can be optimized to provide Development of specialized machines that were optimized prime power energy conversion from the vehicle engine. for this type of pulsed duty was needed. In 1977, the laser This paper, however, will focus on pulsed machines that are fusion community began looking for an alternative power best suited for intermittent and pulsed loads requiring source to capacitor banks for driving laser flashlamps. -

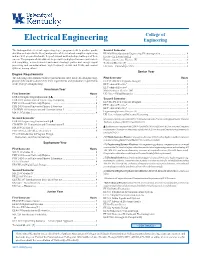

Electrical Engineering Engineering

College of Electrical Engineering Engineering The undergraduate electrical engineering degree program seeks to produce gradu- Second Semester ates who are trained in the theory and practice of electrical and computer engineering EE 468G Introduction to Engineering Electromagnetics ........................................ 4 and are well prepared to handle the professional and leadership challenges of their Elective EE Laboratory [L] ...................................................................................... 2 careers. The program allows students to specialize in high performance and embed- Engineering/Science Elective [E] ............................................................................ 3 ded computing, microelectronics and nanotechnology, power and energy, signal Technical Elective [T] ............................................................................................. 3 processing and communications, high frequency circuits and fields, and control UK Core – Citizenship - USA .................................................................................. 3 systems, among others. Senior Year Degree Requirements The following curriculum meets the requirements for a B.S. in Electrical Engineering, First Semester Hours provided the student satisfies UK Core requirements and graduation requirements EE/CPE 490 ECE Capstone Design I† ..................................................................... 3 of the College of Engineering. EE Technical Elective* ........................................................................................... -

Modeling, Analogue and Tests of an Electric Machine

MODELING, ANALOGUE AND TESTS OF AN ELECTRIC MACHINE VOLTAGE CONTROL SYSTEM 'by GRAHAM E.' DAWSON ( j B.A.Sc, University of British. Columbia, 1963. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS, FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF APPLIED SCIENCE. in the Department of Electrical Engineering We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard Members of the Committee Head of the Department .»»«... Members of the Department of Electrical Engineering THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1966 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely.avai1able for reference and study. I further agree that permission for ex• tensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives.. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for finan• cial gain shall not be allowed without my.written permission. Department of Electrical Engineering The University of British Columbia Vancou ve r.,8, Canada Date 7. MM ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the modeling, analogue and tests of an interconnected four electric machine voltage control system. Many analogue studies of electric machines have been done but most are concerned with the development of analogue techniques and only a few give substantiation of the validity of the analogue models through comparison of results from analogue studies and from real machine tests. Chapter 2 describes the procedure and the system under study. Chapter 3 describes the methods used for the determination of the electrical and mechanical system parameters. -

Power Processing, Part 1. Electric Machinery Analysis

DOCONEIT MORE BD 179 391 SE 029 295,. a 'AUTHOR Hamilton, Howard B. :TITLE Power Processing, Part 1.Electic Machinery Analyiis. ) INSTITUTION Pittsburgh Onii., Pa. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washingtcn, PUB DATE 70 GRANT NSF-GY-4138 NOTE 4913.; For related documents, see SE 029 296-298 n EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 PusiPostage. DESCRIPTORS *College Science; Ciirriculum Develoiment; ElectricityrFlectrOmechanical lechnology: Electronics; *Fagineering.Education; Higher Education;,Instructional'Materials; *Science Courses; Science Curiiculum:.*Science Education; *Science Materials; SCientific Concepts ABSTRACT A This publication was developed as aportion of a two-semester sequence commeicing ateither the sixth cr'seventh term of,the undergraduate program inelectrical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh. The materials of thetwo courses, produced by a ional Science Foundation grant, are concernedwith power convrs systems comprising power electronicdevices, electrouthchanical energy converters, and associated,logic Configurations necessary to cause the system to behave in a prescribed fashion. The emphisis in this portionof the two course sequence (Part 1)is on electric machinery analysis. lechnigues app;icable'to electric machines under dynamicconditions are anallzed. This publication consists of sevenchapters which cW-al with: (1) basic principles: (2) elementary concept of torqueand geherated voltage; (3)tile generalized machine;(4i direct current (7) macrimes; (5) cross field machines;(6),synchronous machines; and polyphase -

Lecture 8: Magnets and Magnetism Magnets

Lecture 8: Magnets and Magnetism Magnets •Materials that attract other metals •Three classes: natural, artificial and electromagnets •Permanent or Temporary •CRITICAL to electric systems: – Generation of electricity – Operation of motors – Operation of relays Magnets •Laws of magnetic attraction and repulsion –Like magnetic poles repel each other –Unlike magnetic poles attract each other –Closer together, greater the force Magnetic Fields and Forces •Magnetic lines of force – Lines indicating magnetic field – Direction from N to S – Density indicates strength •Magnetic field is region where force exists Magnetic Theories Molecular theory of magnetism Magnets can be split into two magnets Magnetic Theories Molecular theory of magnetism Split down to molecular level When unmagnetized, randomness, fields cancel When magnetized, order, fields combine Magnetic Theories Electron theory of magnetism •Electrons spin as they orbit (similar to earth) •Spin produces magnetic field •Magnetic direction depends on direction of rotation •Non-magnets → equal number of electrons spinning in opposite direction •Magnets → more spin one way than other Electromagnetism •Movement of electric charge induces magnetic field •Strength of magnetic field increases as current increases and vice versa Right Hand Rule (Conductor) •Determines direction of magnetic field •Imagine grasping conductor with right hand •Thumb in direction of current flow (not electron flow) •Fingers curl in the direction of magnetic field DO NOT USE LEFT HAND RULE IN BOOK Example Draw magnetic field lines around conduction path E (V) R Another Example •Draw magnetic field lines around conductors Conductor Conductor current into page current out of page Conductor coils •Single conductor not very useful •Multiple winds of a conductor required for most applications, – e.g. -

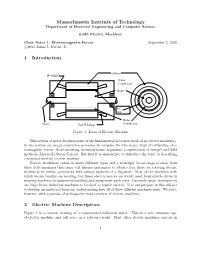

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1 Introduction 2 Electric Machine

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 6.685 Electric Machines Class Notes 1: Electromagnetic Forces September 5, 2005 c 2003 James L. Kirtley Jr. 1 Introduction Stator Bearings Stator Conductors Rotor Air Gap Rotor Shaft End Windings Conductors Figure 1: Form of Electric Machine This section of notes discusses some of the fundamental processes involved in electric machinery. In the section on energy conversion processes we examine the two major ways of estimating elec- tromagnetic forces: those involving thermodynamic arguments (conservation of energy) and field methods (Maxwell’s Stress Tensor). But first it is appropriate to introduce the topic by describing a notional rotating electric machine. Electric machinery comes in many different types and a strikingly broad range of sizes, from those little machines that cause cell ’phones and pagers to vibrate (yes, those are rotating electric machines) to turbine generators with ratings upwards of a Gigawatt. Most of the machines with which we are familiar are rotating, but linear electric motors are widely used, from shuttle drives in weaving machines to equipment handling and amusement park rides. Currently under development are large linear induction machines to be used to launch aircraft. It is our purpose in this subject to develop an analytical basis for understanding how all of these different machines work. We start, however, with a picture of perhaps the most common of electric machines. 2 Electric Machine Description: Figure 1 is a cartoon drawing of a conventional induction motor. This is a very common type of electric machine and will serve as a reference point.