Reducing Tensions Between Russia and NATO Reducing Tensions Between Russia and NATO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia 2016 Human Rights Report

GEORGIA 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT Note: Except where otherwise noted, figures and other data do not include the occupied regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The constitution provides for an executive branch that reports to the prime minister, a unicameral parliament, and a separate judiciary. The government is accountable to parliament. The president is the head of state and commander in chief. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) termed the October parliamentary elections competitive and administered in a manner that respected the rights of candidates and voters, but it stated that the open campaign atmosphere was affected by allegations of unlawful campaigning and incidents of violence. According to the ODIHR, election commissions and courts often did not respect the principle of transparency and the right to effective redress between the first and second rounds, which weakened confidence in the election administration. In the 2013 presidential election, the OSCE/ODIHR concluded the vote “was efficiently administered, transparent and took place in an amicable and constructive environment.” While the election results reflected the will of the people, observers noted several problems, including allegations of political pressure at the local level, inconsistent application of the election code, and limited oversight of alleged campaign finance violations. Civilian authorities maintained effective control of the security forces. The -

Minsk II a Fragile Ceasefire

Briefing 16 July 2015 Ukraine: Follow-up of Minsk II A fragile ceasefire SUMMARY Four months after leaders from France, Germany, Ukraine and Russia reached a 13-point 'Package of measures for the implementation of the Minsk agreements' ('Minsk II') on 12 February 2015, the ceasefire is crumbling. The pressure on Kyiv to contribute to a de-escalation and comply with Minsk II continues to grow. While Moscow still denies accusations that there are Russian soldiers in eastern Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin publicly admitted in March 2015 to having invaded Crimea. There is mounting evidence that Moscow continues to play an active military role in eastern Ukraine. The multidimensional conflict is eroding the country's stability on all fronts. While the situation on both the military and the economic front is acute, the country is under pressure to conduct wide-reaching reforms to meet its international obligations. In addition, Russia is challenging Ukraine's identity as a sovereign nation state with a wide range of disinformation tools. Against this backdrop, the international community and the EU are under increasing pressure to react. In the following pages, the current status of the Minsk II agreement is assessed and other recent key developments in Ukraine and beyond examined. This briefing brings up to date that of 16 March 2015, 'Ukraine after Minsk II: the next level – Hybrid responses to hybrid threats?'. In this briefing: • Minsk II – still standing on the ground? • Security-related implications of the crisis • Russian disinformation -

Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference 1 The Conference All three leaders were attempting to establish an agenda for governing post-war Europe. They wanted to keep peace between post-world war countries. On the Eastern Front, the front line at the end of December 1943 re- mained in the Soviet Union but, by August 1944, So- viet forces were inside Poland and parts of Romania as part of their drive west.[1] By the time of the Conference, Red Army Marshal Georgy Zhukov's forces were 65 km (40 mi) from Berlin. Stalin’s position at the conference was one which he felt was so strong that he could dic- tate terms. According to U.S. delegation member and future Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, "[i]t was not a question of what we would let the Russians do, but what Yalta Conference in February 1945 with (from left to right) we could get the Russians to do.”[2] Moreover, Roosevelt Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin. Also hoped for a commitment from Stalin to participate in the present are Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (far left); United Nations. Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew Cunningham, RN, Marshal of the RAF Sir Charles Portal, RAF, Premier Stalin, insisting that his doctors opposed any (standing behind Churchill); General George C. Marshall, Chief long trips, rejected Roosevelt’s suggestion to meet at the of Staff of the United States Army, and Fleet Admiral William Mediterranean.[3] He offered instead to meet at the Black D. Leahy, USN, (standing behind Roosevelt). -

The BCCI Affair

The BCCI Affair A Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate by Senator John Kerry and Senator Hank Brown December 1992 102d Congress 2d Session Senate Print 102-140 This December 1992 document is the penultimate draft of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee report on the BCCI Affair. After it was released by the Committee, Sen. Hank Brown, reportedly acting at the behest of Henry Kissinger, pressed for the deletion of a few passages, particularly in Chapter 20 on "BCCI and Kissinger Associates." As a result, the final hardcopy version of the report, as published by the Government Printing Office, differs slightly from the Committee's softcopy version presented below. - Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists This report was originally made available on the website of the Federation of American Scientists. This version was compiled in PDF format by Public Intelligence. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF INVESTIGATION ............................................................................... 21 THE ORIGIN AND EARLY YEARS OF BCCI .................................................................................................... 25 BCCI'S CRIMINALITY .................................................................................................................................. 49 BCCI'S RELATIONSHIP WITH FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS CENTRAL BANKS, AND INTERNATIONAL -

Atlantic Countries' Voting Patterns on Human Rights and Human

12 Atlantic countries’ voting patterns on human rights and human security at the United Nations: the cases of Côte d’Ivoire, Haiti, Iran and Syria Susanne Gratius Associate Research Fellow, FRIDE ABSTRACT An analysis of the voting patterns at the United Nations (UN) on human rights and human security helps identify points of convergence or divergence among the countries of the Atlantic basin with regard to values and approaches to international crises. This paper explores if such countries, or groups of countries within the Atlantic basin, share political concepts and values. Based on four case studies – Iran, Syria, Haiti and Côte d’Ivoire – the paper assesses the similarities and differences regarding conflict resolution and responses to massive human rights violations. The first section reviews the current debate over the UN principle of “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P), notably in relation to the Brazilian concept of “Responsibility while Protecting” (RwP). It looks at the perceptions of Atlantic countries, groups and alliances on issues of national sovereignty, sanctions and military interventions authorized by the UN Security Council (UNSC). The second section focuses on the initiatives and positions of Atlantic countries and regional organizations and their alignments at the UN Security Council, the UN General Assembly, and the UN Human Rights Council (HRC). The section concentrates on their voting patterns concerning four cases in particular: two outside the Atlantic space (Syria and Iran) and two inside (Haiti and Côte d’Ivoire). These four countries have been selected because they represent different types of conflicts: Iran and Syria are international hotspots and suppose, albeit for very different reasons, potential threats for regional peace and global stability; Haiti and Côte d’Ivoire rank high on the list of fragile states and the international community has been highly engaged in crisis management and stabilization in these countries. -

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson SILK ROAD PAPER January 2018 Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center American Foreign Policy Council, 509 C St NE, Washington D.C. Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program, Joint Center. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council and the Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of -

UNITED NATIONS Governing Council of the United Nations Environment

UNITED NATIONS EP UNEP/GCSS.IX/11 Distr.: General Governing Council 16 March 2006 of the United Nations Environment Programme Original: English Ninth special session of the Governing Council/ Global Ministerial Environment Forum Dubai, 7–9 February 2006 Proceedings of the Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum at its ninth special session Introduction The ninth special session of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum was held at the Dubai International Convention Centre in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, from 7 to 9 February 2006. It was convened in pursuance of paragraph 1 (g) of Governing Council decision 20/17 of 5 February 1999, entitled “Views of the Governing Council on the report of the Secretary-General on environment and human settlements”; Governing Council decision 23/12 of 7 April 2005, entitled “Provisional agendas, dates and venues of the ninth special session of the Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum and the twenty-fourth session of the Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum”, paragraph 6 of General Assembly resolution 53/242 of 28 July 1999, entitled “Report of the Secretary-General on environment and human settlements”; and paragraph 5 of General Assembly resolution 40/243 of 18 December 1985, entitled “Pattern of conferences”; and in accordance with rules 5 and 6 of the rules of procedure of the Governing Council. I. Opening of the session A. Ceremonial opening 1. The ceremonial opening of the ninth special session of the UNEP Governing Council/Global Ministerial Environment Forum was held on Monday, 6 February 2006, in conjunction with the award ceremony for the third Zayed International Prize for the Environment. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

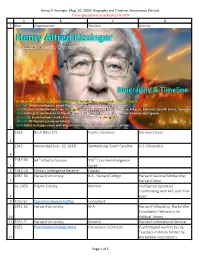

Henry A. Kissinger. (Aug

Henry A. Kissinger. (Aug. 20, 2020). Biography and Timeline. Anonymous Patriots. *.xlsx spreadsheet attached to this PDF A B C D 1 Year Organization Position Activity Henry Alfred Kissinger (b. 1923, Fuerth, Germany) Biography & Timeline Dedicated his career to the (British) Pilgrims Society "new world order" 200-year plan ca. 1948: British intelligence; joined Pilgrims Society; Pilgrims Rockefeller "advisor" 1948: Runner for the Marshall Plan stolen gold created by Pilgrims Society Stimson, Acheson, Marshall, Sarnoff, Dulles, Donovan 1971: Killed gold standard w/ 12 Nixon Pilgrims Cabinet members incl. Volcker; ran American intelligence 1971-2008: Exploited Swiss Bank of International Settlements stolen gold 2007-09: VP Pilgrims Society w/ Volcker 2008: Killed mortgage values with Pilgrims Clinton, Bush, Obama, Summers, Volcker 2 1923 Birth (May 27) Fuerth, Germany German Citizen 3 1943 Naturalized (Jun. 19, 1943) Spartanburg, South Carolina U.S. Citizenship 4 1943-46 84th Infantry Division 970th Counter-Intelligence 5 Corps 6 1946-59 Military Intelligence Reserve Captain 1947-50 Harvard University B.A., Harvard College Harvard National Scholarship; 7 Harvard Detur ca. 1950 Pilgrim Society Member Intelligence operative coordinating with MI6 and "Five 8 Eyes" 9 1950-61 Operations Research Office Consultant 1951-52 Harvard University M.A. Harvard Fellowship; Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship for 10 Political Theory 11 1951-71 Harvard University Director Harvard International Seminar 1952 Psychological Strategy Board Consultant to Director Psychological warfare (using Tavistock Institute funded by 12 Rockefeller Foundation) Page 1 of 5 Henry A. Kissinger. (Aug. 20, 2020). Biography and Timeline. Anonymous Patriots. *.xlsx spreadsheet attached to this PDF A B C D 1 Year Organization Position Activity 13 1952-54 Harvard University Ph.D. -

Georgia/Abkhazia

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH ARMS PROJECT HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/HELSINKI March 1995 Vol. 7, No. 7 GEORGIA/ABKHAZIA: VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OF WAR AND RUSSIA'S ROLE IN THE CONFLICT CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................................5 EVOLUTION OF THE WAR.......................................................................................................................................6 The Role of the Russian Federation in the Conflict.........................................................................................7 RECOMMENDATIONS...............................................................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Republic of Georgia ..............................................................................................8 To the Commanders of the Abkhaz Forces .....................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Russian Federation................................................................................................8 To the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus...........................................................................9 To the United Nations .....................................................................................................................................9 To the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe..........................................................................9 -

Fact Sheet on "Overview of Norway"

Legislative Council Secretariat FSC21/13-14 FACT SHEET Overview of Norway Geography Land area Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is located in northern Europe. It has a total land area of 304 282 sq km divided into 19 counties. Oslo is the capital of the country and seat of government. Demographics Population Norway had a population of about 5.1 million at end-July 2014. The majority of the population were Norwegian (94%), followed by ethnic minority groups such as Polish, Swedish and Pakistanis. History Political ties Norway has a history closely linked to that of its immediate with neighbours, Sweden and Denmark. Norway had been an Denmark and independent kingdom in its early period, but lost its Sweden independence in 1380 when it entered into a political union with Denmark through royal intermarriage. Subsequently both Norway and Denmark formed the Kalmar Union with Sweden in 1397, with Denmark as the dominant power. Following the withdrawal of Sweden from the Union in 1523, Norway was reduced to a dependence of Denmark in 1536 under the Danish-Norwegian Realm. Union The Danish-Norwegian Realm was dissolved in between January 1814, when Denmark ceded Norway to Sweden as Norway and part of the Kiel Peace Agreement. That same year Sweden Norway – tired of forced unions – drafted and adopted its own Constitution. Norway's struggle for independence was subsequently quelled by a Swedish invasion. In the end, Norwegians were allowed to keep their new Constitution, but were forced to accept the Norway-Sweden Union under a Swedish king. Research Office page 1 Legislative Council Secretariat FSC21/13-14 History (cont'd) Independence The Sweden-Norway Union was dissolved in 1905, after the of Norway Norwegians voted overwhelmingly for independence in a national referendum. -

“Techno-Diplomacy” for the Twenty-First Century: Lessons of U.S.-Soviet Space Cooperation for U.S.-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic

THE HURFORD FOUNDATION 2015-2016 HURFORD NEXT GENERATION FELLOWSHIP RESEARCH PAPERS No. 6 “TECHNO-DIPLOMACY” FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: LESSONS OF U.S.-SOVIET SPACE COOPERATION FOR U.S.-RUSSIAN COOPERATION IN THE ARCTIC Rachel S. Salzman EASI-Hurford Next Generation Fellow The Hurford Fellows Program is sponsored by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and is made possible by a generous grant from the Hurford Foundation THE HURFORD FOUNDATION The Hurford Fellowships, administered by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, support the Euro- Atlantic Security Initiative (EASI) Next Generation Network in identifying young academics conducting innovative research on international security in the Euro- Atlantic area. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Cooperation and Techno-Diplomacy: Some Definitions ......................................................... 4 Learning the Wrong Lessons: Is the Cold War Really the Right Frame? ............................ 6 From “the Pearl Harbor of American Science” to the “Handshake in Space”: U.S.- Soviet Space Cooperation ................................................................................................................... 7 The Good .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 The Bad .............................................................................................................................................................