LIFE in the CAMPS: Introduction. Several Asylum Seekers Has Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MONITORING of MARINE MAMMALS in HONG KONG WATERS (2013-14) FINAL REPORT (1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014)

MONITORING OF MARINE MAMMALS IN HONG KONG WATERS (2013-14) FINAL REPORT (1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014) Submitted by Samuel K.Y. Hung, Ph.D. Hong Kong Cetacean Research Project © Samuel Hung / HKDCS © HKCRP Submitted to the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department of the Hong Kong SAR Government Tender Re.: AFCD/SQ/183/12 1 June 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS DRAFT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……………………………….……………...... 5 行政摘要 (中文翻譯) …………………………………………………………….. 8 1. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………..... 11 2. OBJECTIVES OF PRESENT STUDY ………………………………………. 12 3. RESEARCH TASKS …………………………………………………………. 13 4. METHODOLOGY …………….………………………………………….….. 13 4.1. Vessel Survey 4.2. Helicopter Survey 4.3. Photo-identification Work with Focal Follow Study 4.4. Dolphin-related Acoustic Works 4.4.1. Calibrated hydrophone 4.4.2. Towed hydrophone 4.5. Shore-based Theodolite Tracking Work 4.6. Data Analyses 4.6.1. Distribution pattern analysis 4.6.2. Encounter rate analysis 4.6.3. Line-transect analysis 4.6.4. Quantitative grid analysis on habitat use 4.6.5. Behavioural analysis 4.6.6. Ranging pattern analysis 4.6.7. Residency pattern analysis 4.6.8. Movement pattern analysis 5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS 5.1. Summary of Data Collection ………………………………….…..….….. 23 5.1.1. Survey effort 5.1.2. Marine Mammal Sightings 5.1.3. Photo-identification of Individual Dolphins 5.1.4. Dolphin-related Acoustic Studies 2 5.1.5. Shore-based Theodolite Tracking 5.2. Distribution ……… …..…………….. …………………………………. 28 5.2.1. Distribution of Chinese White Dolphins 5.2.2. Distribution of finless porpoises 5.3. Encounter Rate ……..…………………………….………………….…. 31 5.3.1. Encounter rates of Chinese White Dolphins 5.3.2. -

List of Recognized Villages Under the New Territories Small House Policy

LIST OF RECOGNIZED VILLAGES UNDER THE NEW TERRITORIES SMALL HOUSE POLICY Islands North Sai Kung Sha Tin Tuen Mun Tai Po Tsuen Wan Kwai Tsing Yuen Long Village Improvement Section Lands Department September 2009 Edition 1 RECOGNIZED VILLAGES IN ISLANDS DISTRICT Village Name District 1 KO LONG LAMMA NORTH 2 LO TIK WAN LAMMA NORTH 3 PAK KOK KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 4 PAK KOK SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 5 SHA PO LAMMA NORTH 6 TAI PENG LAMMA NORTH 7 TAI WAN KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 8 TAI WAN SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 9 TAI YUEN LAMMA NORTH 10 WANG LONG LAMMA NORTH 11 YUNG SHUE LONG LAMMA NORTH 12 YUNG SHUE WAN LAMMA NORTH 13 LO SO SHING LAMMA SOUTH 14 LUK CHAU LAMMA SOUTH 15 MO TAT LAMMA SOUTH 16 MO TAT WAN LAMMA SOUTH 17 PO TOI LAMMA SOUTH 18 SOK KWU WAN LAMMA SOUTH 19 TUNG O LAMMA SOUTH 20 YUNG SHUE HA LAMMA SOUTH 21 CHUNG HAU MUI WO 2 22 LUK TEI TONG MUI WO 23 MAN KOK TSUI MUI WO 24 MANG TONG MUI WO 25 MUI WO KAU TSUEN MUI WO 26 NGAU KWU LONG MUI WO 27 PAK MONG MUI WO 28 PAK NGAN HEUNG MUI WO 29 TAI HO MUI WO 30 TAI TEI TONG MUI WO 31 TUNG WAN TAU MUI WO 32 WONG FUNG TIN MUI WO 33 CHEUNG SHA LOWER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 34 CHEUNG SHA UPPER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 35 HAM TIN SOUTH LANTAU 36 LO UK SOUTH LANTAU 37 MONG TUNG WAN SOUTH LANTAU 38 PUI O KAU TSUEN (LO WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 39 PUI O SAN TSUEN (SAN WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 40 SHAN SHEK WAN SOUTH LANTAU 41 SHAP LONG SOUTH LANTAU 42 SHUI HAU SOUTH LANTAU 43 SIU A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 44 TAI A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 3 45 TAI LONG SOUTH LANTAU 46 TONG FUK SOUTH LANTAU 47 FAN LAU TAI O 48 KEUNG SHAN, LOWER TAI O 49 KEUNG SHAN, -

EP) Provision of Compensatory Marine Park for Integrated Waste Management Facilities at an Artificial Island Near Shek Kwu Chau – Investigation”(The Study

Agreement No. CE 14/2012 (EP) Provision of Compensatory Marine Park for Integrated Waste Management Facilities at an Artificial Island near Shek Kwu Chau – Investigation Executive Summary 07 November 2019 Environmental Resources Management 2507, 25/F, One Habrourfront 18 Tak Fung Street Hunghom, Kowloon Hong Kong Telephone 2271 3000 Facsimile 2723 5660 www.erm.com Environmental Resources Agreement No. CE 14/2012 (EP Management Provision of Compensatory Marine 2507, 25/F, Park for Integrated Waste One Habrourfront 18 Tak Fung Street Management Facilities at an Hunghom, Kowloon Artificial Island near Shek Kwu Hong Kong Telephone: (852) 2271 3000 Chau – Investigation Facsimile: (852) 2723 5660 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.erm.com Executive Summary Document Code: 0302663_Executive Summary_v4.docx Client: Project No: Environmental Protection Department (EPD) 0302663 Summary: Date: 07 November 2019 Approved by: This document presents the Executive Summary for the EPD consultancy (Agreement No. CE 14/2012(EP)) Provision of Compensatory Marine Park for Integrated Waste Management Facilities at an Artificial Island near Shek Kwu Chau – Investigation. Craig A Reid Partner 4 Executive Summary Var JT CAR 7/11/19 3 Executive Summary Var JT CAR 16/10/19 2 Executive Summary Var JT CAR 3/7/19 1 Executive Summary Var JT CAR 6/5/19 0 Executive Summary (Draft) CY JT CAR 1/2/19 Revision Description By Checked Approved Date Distribution Internal Government Confidential CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY 1 1.2 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY -

Office Address of the Labour Relations Division

If you wish to make enquiries or complaints or lodge claims on matters related to the Employment Ordinance, the Minimum Wage Ordinance or contracts of employment with the Labour Department, please approach, according to your place of work, the nearby branch office of the Labour Relations Division for assistance. Office address Areas covered Labour Relations Division (Hong Kong East) (Eastern side of Arsenal Street), HK Arts Centre, Wan Chai, Causeway Bay, 12/F, 14 Taikoo Wan Road, Taikoo Shing, Happy Valley, Tin Hau, Fortress Hill, North Point, Taikoo Place, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong. Shau Ki Wan, Chai Wan, Tai Tam, Stanley, Repulse Bay, Chung Hum Kok, South Bay, Deep Water Bay (east), Shek O and Po Toi Island. Labour Relations Division (Hong Kong West) (Western side of Arsenal Street including Police Headquarters), HK Academy 3/F, Western Magistracy Building, of Performing Arts, Fenwick Pier, Admiralty, Central District, Sheung Wan, 2A Pok Fu Lam Road, The Peak, Sai Ying Pun, Kennedy Town, Cyberport, Residence Bel-air, Hong Kong. Aberdeen, Wong Chuk Hang, Deep Water Bay (west), Peng Chau, Cheung Chau, Lamma Island, Shek Kwu Chau, Hei Ling Chau, Siu A Chau, Tai A Chau, Tung Lung Chau, Discovery Bay and Mui Wo of Lantau Island. Labour Relations Division (Kowloon East) To Kwa Wan, Ma Tau Wai, Hung Hom, Ho Man Tin, Kowloon City, UGF, Trade and Industry Tower, Kowloon Tong (eastern side of Waterloo Road), Wang Tau Hom, San Po 3 Concorde Road, Kowloon. Kong, Wong Tai Sin, Tsz Wan Shan, Diamond Hill, Choi Hung Estate, Ngau Chi Wan and Kowloon Bay (including Telford Gardens and Richland Gardens). -

Marine Department Notice No. 7/2020

MARINE DEPARTMENT NOTICE NO. 7/2020 (Miscellaneous Information) Yacht Races between Hong Kong and Macau NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that yacht races between Hong Kong and Macau will take place on 25 January 2020 (Saturday) and 27 January 2020 (Monday). About 18 sailing boats are expected to participate in the races. 2. The outbound trip from Hong Kong to Macau will start at 1000 hours on 25 January 2020 in an area east of Cheung Chau. It will follow a south-westerly route through the southern Boundary of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, thence to Macau. 3. The return trip from Macau to Hong Kong will start at 1100 hours on 27 January 2020. It will follow a route through south of Dazhi Zhou and complete the race at a position south of Shek Kwu Chau. 4. Masters, coxswains and persons-in-charge of vessels navigating in the vicinity of the racing routes should proceed with caution, giving practical consideration to the contestants. Compliance with the provisions of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea 1972 is mandatory. 5. A drawing showing the race routes is attached to this Notice. Agnes WONG Director of Marine Marine Department Government of the HKSAR Date: 9 January 2020 Action File Ref.: L/M No. 066/2019 in PA/S AMO 922(11) We are One in Promoting Excellence in Marine Services 海事處佈告第 7 /2020 號 附圖 Drawing Attached to Marine Department Notice No. 7/2020 伶 仃 洋 珠 海 LINGDING YANG ZHUHAI 香 港 島 大 嶼 山 HONG KONG LANTAU ISLAND ISLAND 長 洲 Cheung 起 點 Chau Start 澳 門 南丫島 MACAU LAMMA 石鼓洲 ISLAND 大 嶼 海 峽 圓 角 LANTAU CHANNEL 終 點 Shek Kwu Chau Yuen Kok 牛 頭 島 Finish 大 鴉 洲 NIUTOU TAI A CHAU ISLAND 氹 仔 ILHADA TAIPA Boundary of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 桂 山 島 GUISHAN 小 蜘 洲 大 蜘 洲 ISLAND 担 杆 水 道 DANGAN CHANNEL 終 點/起 點 XIAOZHI DAZHI ZHOU 大 碌 島 ZHOU Finish/Start DALU ISLAND 外 伶 仃 島 大 頭 洲 DATOU WAILINGDING ISLAND ZHOU 圖例 Map Legend 賽道 Course 起點及終點 Starting Points and Finishing Points 不宜作航行用途 NOT TO BE USED FOR NAVIGATION . -

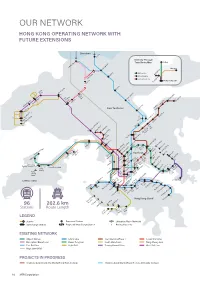

Our Network Hong Kong Operating Network with Future Extensions

OUR NETWORK HONG KONG OPERATING NETWORK WITH FUTURE EXTENSIONS Shenzhen Lo Wu Intercity Through Train Route Map Beijing hau i C Lok Ma Shanghai Sheung Shu g Beijing Line Guangzhou Fanlin Shanghai Line Kwu Tung Guangdong Line n HONG KONG SAR Dongguan San Ti Tai Wo Long Yuen Long t Ping 48 41 47 Ngau a am Tam i Sh i K Mei a On Shan a Tai Po Marke 36 K Sheungd 33 M u u ui Wa W Roa Au Tau Tin Sh 49 Heng On y ui Hung Shui Ki g ng 50 New Territories Tai Sh Universit Han Siu Ho 30 39 n n 27 35 Shek Mu 29 Tuen Mu cecourse* e South Ra o Tan Area 16 F 31 City On Tuen Mun n 28 a n u Sha Ti Sh n Ti 38 Wai Tsuen Wan West 45 Tsuen05 Wa Tai Wo Ha Che Kung 40 Temple Kwai Hing 07 i 37 Tai Wa Hin Keng 06 l Kwai Fong o n 18 Mei Fo k n g Yi Diamond Hil Kowloon Choi Wa Tsin Tong n i King Wong 25 Shun Ti La Lai Chi Ko Lok Fu d Tai Si Choi Cheung Sha Wan Hung Sau Mau Ping ylan n ay e Sham Shui Po ei Kowloon ak u AsiaWorld-Expo B 46 ShekM T oo Po Tat y Disn Resort m Po Lam Na Kip Kai k 24 Kowl y Sunn eong g Hang Ha Prince n Ba Ch o Sungong 01 53 Airport M Mong W Edward ok ok East 20 K K Toi ong 04 To T Ho Kwa Ngau Tau Ko Cable Car n 23 Olympic Yau Mai Man Wan 44 n a Kwun Ti Ngong Ping 360 19 52 42 n Te Ti 26 Tung Chung East am O 21 L Tung Austi Yau Tong Tseung Chung on Whampo Kwan Tung o n Jordan Tiu g Kowl loo Tsima Hung 51 Ken Chung w Sh Hom Leng West Hong Kong Tsui 32 t Tsim Tsui West Ko Eas 34 22 ha Fortress10 Hill Hong r S ay LOHAS Park ition ew 09 Lantau Island ai Ying Pun Kong b S Tama xhi aus North h 17 11 n E C y o y Centre Ba Nort int 12 16 Po 02 Tai -

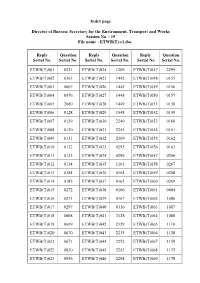

Secretary for the Environment, Transport and Works Session No

Index page Director of Bureau: Secretary for the Environment, Transport and Works Session No. : 19 File name : ETWB(T)-e1.doc Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. ETWB(T)001 0231 ETWB(T)024 1209 ETWB(T)047 2295 ETWB(T)002 0363 ETWB(T)025 1442 ETWB(T)048 0155 ETWB(T)003 0607 ETWB(T)026 1445 ETWB(T)049 0156 ETWB(T)004 0976 ETWB(T)027 1448 ETWB(T)050 0157 ETWB(T)005 2080 ETWB(T)028 1449 ETWB(T)051 0158 ETWB(T)006 0128 ETWB(T)029 1548 ETWB(T)052 0159 ETWB(T)007 0129 ETWB(T)030 2240 ETWB(T)053 0160 ETWB(T)008 0130 ETWB(T)031 2245 ETWB(T)054 0161 ETWB(T)009 0131 ETWB(T)032 2309 ETWB(T)055 0162 ETWB(T)010 0132 ETWB(T)033 0295 ETWB(T)056 0163 ETWB(T)011 0133 ETWB(T)034 0296 ETWB(T)057 0266 ETWB(T)012 0134 ETWB(T)035 1161 ETWB(T)058 0267 ETWB(T)013 0184 ETWB(T)036 0164 ETWB(T)059 0268 ETWB(T)014 0185 ETWB(T)037 0165 ETWB(T)060 0269 ETWB(T)015 0272 ETWB(T)038 0166 ETWB(T)061 0604 ETWB(T)016 0273 ETWB(T)039 0167 ETWB(T)062 1086 ETWB(T)017 0297 ETWB(T)040 0316 ETWB(T)063 1087 ETWB(T)018 0668 ETWB(T)041 2128 ETWB(T)064 1088 ETWB(T)019 0669 ETWB(T)042 2129 ETWB(T)065 1110 ETWB(T)020 0670 ETWB(T)043 2235 ETWB(T)066 1158 ETWB(T)021 0671 ETWB(T)044 2252 ETWB(T)067 1159 ETWB(T)022 0830 ETWB(T)045 2253 ETWB(T)068 1172 ETWB(T)023 0956 ETWB(T)046 2294 ETWB(T)069 1178 Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. -

Egretries in Hong Kong

Committee Paper NCSC 7/06 Advisory Council on the Environment Nature Conservation Subcommittee Egretries in Hong Kong Purpose The Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD) has commissioned the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (HKBWS) to carry out a territory-wide egretry survey in Hong Kong since 1998. This paper provides an overview of the egretries in Hong Kong based on a review of historical records and results of the surveys carried out by the HKBWS. It also describes AFCD’s work in conservation and management of egretries. Background 2. Members of the family Ardeidae (i.e. herons and egrets) nest in colonies forming an egretry, which sometimes contain different ardeid species, with the size ranged from a few pairs to several thousands. In Hong Kong, there are five main species of ardeids, namely Little Egret (Egretta garzetta), Great Egret (Egretta alba), Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis), Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) and Chinese Pond Heron (Ardeola bacchus), currently breeding in colonies. The numbers of active nest/nesting pair of ardeids in breeding colonies of Hong Kong were monitored by volunteers of the HKBWS as early as 1950’s and up to 1975. However, such reporting was suspended between 1975 and 1989. 3. In Hong Kong, egrets and herons generally breed between mid March and August each year. The breeding periods may vary between different locations and species, or affected by poor weather conditions. For example, high frequency of typhoon in a particular year may lengthen the breeding period to September or October. 4. Egrets and herons nest in colonies and the egretries may be used for many years in succession. -

Marine Department Notice No. 1/2020

MARINE DEPARTMENT NOTICE NO. 1/2020 (Miscellaneous Information) HONG KONG MARINE DEPARTMENT NOTICES The following Marine Department Notices (MDN) are still in force as at 1 January 2020 : (I) Navigation Warnings & Related Information MDN Issue Date Tung Chung New Town Extension Project Temporary Arrangement of the Tung Chung 70/18 03/05/18 Buoyed Channel Typhoon Season 97/19 31/05/19 (II) Establishment, Withdrawal and Changes of Aids to Navigation, Fairways, Anchorages & Other MDN Issue Date Port Facilities Changes to the Ship’s Routeing System and Ship 97/15 30/06/15 Reporting System in the Waters of Pearl River Estuary Establishment of Marker Buoys at Sai Kung and 128/15 24/09/15 Tai Po Continuous Operation of a Temporary Wind Monitoring 37/17 09/03/17 Station off Basalt Island, Sai Kung Re-arrangement of Passage Area in Causeway Bay 99/17 06/07/17 Typhoon Shelter Withdrawal of Light Buoy “Airport 3” off Hong Kong 15/18 02/02/18 International Airport Temporary Establishment of Scientific Research Buoy 83/18 16/05/18 “SKLMP 1” to the Southwest of Tai A Chau Floating Barriers Across Starling Inlet 122/18 02/08/18 Establishment of Lights on Government Mooring Buoys 124/18 09/08/18 off Tso Wo Hang, Sai Kung Temporary Withdrawal of Weather Buoys To the South 134/18 24/08/18 of Cheung Chau, and To the Southeast of Sha Chau Establishment of Aids to Navigation on the Hong Kong 186/18 27/11/18 Link Road We are One in Promoting Excellence in Marine Services - 2 - (II) Establishment, Withdrawal and Changes of Aids to Navigation, Fairways, Anchorages -

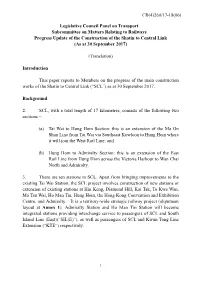

Administration's Paper on Progress Update of the Construction of The

CB(4)260/17-18(06) Legislative Council Panel on Transport Subcommittee on Matters Relating to Railways Progress Update of the Construction of the Shatin to Central Link (As at 30 September 2017) (Translation) Introduction This paper reports to Members on the progress of the main construction works of the Shatin to Central Link (“SCL”) as at 30 September 2017. Background 2. SCL, with a total length of 17 kilometres, consists of the following two sections – (a) Tai Wai to Hung Hom Section: this is an extension of the Ma On Shan Line from Tai Wai via Southeast Kowloon to Hung Hom where it will join the West Rail Line; and (b) Hung Hom to Admiralty Section: this is an extension of the East Rail Line from Hung Hom across the Victoria Harbour to Wan Chai North and Admiralty. 3. There are ten stations in SCL. Apart from bringing improvements to the existing Tai Wai Station, the SCL project involves construction of new stations or extension of existing stations at Hin Keng, Diamond Hill, Kai Tak, To Kwa Wan, Ma Tau Wai, Ho Man Tin, Hung Hom, the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, and Admiralty. It is a territory-wide strategic railway project (alignment layout at Annex 1). Admiralty Station and Ho Man Tin Station will become integrated stations providing interchange service to passengers of SCL and South Island Line (East)(“SIL(E)”), as well as passengers of SCL and Kwun Tong Line Extension (“KTE”) respectively. 1 4. The entire SCL project is funded by the Government under the “concession approach”. -

Hong Kong Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2021

Hong Kong Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2021 Environment Bureau A December 2016 B Table of Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................... 2 List of abbreviations........................................................................................ 3 1 Introduction .................................................................................... 4 1.1 Biodiversity matters 1.2 Overview of Hong Kong’s biodiversity 2 Present Status .............................................................................. 10 2.1 Protection of ecosystems 2.2 Conservation of species and genetic diversity 2.3 Education and public awareness 2.4 Sustainable development 3 Challenges and Threats ............................................................. 32 3.1 Urbanisation and development 3.2 Habitat degradation 3.3 Over-exploitation of biological resources 3.4 Invasive alien species 3.5 Climate change 3.6 Filling information gaps and raising public awareness 4 Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan ................................38 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Formulating a city-level BSAP for Hong Kong 4.3 Vision and Mission 4.4 Area 1: Enhancing conservation measures 4.5 Area 2: Mainstreaming biodiversity 4.6 Area 3: Improving our knowledge 4.7 Area 4: Promoting community involvement 5 Implementation ...........................................................................84 5.1 Funding support 5.2 Implementation and coordination parties 5.3 Advisory body 5.4 Monitoring, -

Annual Report 2020 Stock Code: 66

Keep Cities Moving Annual Report 2020 Stock code: 66 SUSTAINABLE CARING INNOVATIVE CONTENTS For over four decades, MTR has evolved to become one of the leaders in rail transit, connecting communities in Hong Kong, the Mainland of China and around the world with unsurpassed levels of service reliability, comfort and safety. In our Annual Report 2020, we look back at one of the most challenging years in our history, a time when our Company worked diligently in the midst of an unprecedented global pandemic to continue delivering high operational standards while safeguarding the well-being of our customers and colleagues – striving, as always, to keep cities moving. Despite the adverse circumstances, we were still able to achieve our objective of planning an exciting strategic direction. This report also introduces our Corporate Strategy, “Transforming the Future”, which outlines how innovation, technology and, most importantly, sustainability and robust environmental, social and governance practices will shape the future for MTR. In addition, we invite you Keep Cities to read our Sustainability Report 2020, which covers how relevant Moving and material sustainability issues are managed and integrated into our business strategies. We hope that together, these reports offer valuable insights into the events of the past year and the steps we plan on taking toward helping Hong Kong and other cities we serve realise a promising long-term future. Annual Report Sustainability 2020 Report 2020 Overview Business Review and Analysis 2 Corporate Strategy