Episode #3 Initiation of the Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019

Saturday 18th May 2019 | 10:00 Music & Memorabilia Auction May 2019 Lot 19 Description Estimate 5 x Doo Wop / RnB / Pop 7" singles. The Temptations - Someday (Goldisc £15.00 - £25.00 3001). The Righteous Brothers - Along Came Jones (Verve VK-10479). The Jesters - Please Let Me Love You (Winley 221). Wayne Cochran - The Coo (Scottie 1303). Neil Sedaka - Ring A Rockin' (Guyden 2004) Lot 93 Description Estimate 10 x 1980s LPs to include Blondie (2) Parallel Lines, Eat To The Beat. £20.00 - £40.00 Ultravox (2) Vienna, Rage In Eden (with poster). The Pretenders - 2. Men At Work - Business As Usual. Spandau Ballet (2) Journeys To Glory, True. Lot 94 Description Estimate 5 x Rock n Roll 7" singles. Eddie Cochran (2) Three Steps To Heaven £15.00 - £25.00 (London American Recordings 45-HLG 9115), Sittin' On The Balcony (Liberty F55056). Jerry Lee Lewis - Teenage Letter (Sun 384). Larry Williams - Slow Down (Speciality 626). Larry Williams - Bony Moronie (Speciality 615) Lot 95 Description Estimate 10 x 1960s Mod / Soul 7" Singles to include Simon Scott With The LeRoys, £15.00 - £25.00 Bobby Lewis, Shirley Ellis, Bern Elliot & The Fenmen, Millie, Wilson Picket, Phil Upchurch Combo, The Rondels, Roy Head, Tommy James & The Shondells, Lot 96 Description Estimate 2 x Crass LPs - Yes Sir, I Will (Crass 121984-2). Bullshit Detector (Crass £20.00 - £40.00 421984/4) Lot 97 Description Estimate 3 x Mixed Punk LPs - Culture Shock - All The Time (Bluurg fish 23). £10.00 - £20.00 Conflict - Increase The Pressure (LP Mort 6). Tom Robinson Band - Power In The Darkness, with stencil (EMI) Lot 98 Description Estimate 3 x Sub Humanz LPs - The Day The Country Died (Bluurg XLP1). -

Koleksi Musik Hendi Hendratman 70'S, 80'S & 90'S

Hendi Hendratman Music Collection Koleksi Musik Hendi Hendratman 70’s, 80’s & 90’s dst (Slow, Pop, Jazz, Reggae, Disco, Rock, Heavy Metal dll) 10 Cc - I'm Not In Love 10 Cc - Rubber Bullets 10000 Maniacs - What's The Matter Here 12 Stones - Lie To Me 20 Fingers - Lick It (Radio Mix) 21 Guns - Just A Wish 21 Guns - These Eyes 2xl - Disciples Of The Beat 3 Strange Days - School Of Fish 4 Non Blondes - What's Up 4 The Cause - Let Me Be 4 The Cause - Stand By Me 4 X 4 - Fresh One 68's - Sex As A Weapon 80's Console Allstars Vs Modern Talking Medley 98 Degrees - Because Of U 999 - Homicide A La Carte - Tell Him A Plus D - Whip My Hair Whip It Real Good A Taste Of Honey - Sukiyaki A Tear Fell A1 - Be The First To Believe Aaron Carter - (Have Some) Fun With The Funk Aaron Neville - Tell It Like It Is Ace - How Long Adam Hicks - Livin' On A High Wire Adam Wakeman - Owner Of A Lonely Heart Adina Howard - Freak Like Me Adrian Belew - Oh Daddy African Rhythm - Fresh & Fly After 7 - Till You Do Me Right After One - Real Sadness Ii Agnetha Faltskog & Tomas Ledin - Never Again Aileene Airbourne - Ready To Rock Airbourne - Runnin' Wild Airplay - Should We Carry On Al B. Sure - Night & Day Al Bano & Romina Power - Felicita Al Martino - Volare Alan Berry - Come On Remix Alan Jackson - Little Man Alan Ross - The Last Wall Albert One - Heart On Fire Aleph - Big Brothers Alex Dance - These Words Between Us Alex Gopher - Neon Disco Alias - More Than Words Can Say Alias - Waiting For Love Alisha - All Night Passion Alisha - Too Turned On Alison Krawss - When -

Synthpop: Into the Digital Age Morrow, C (1999) Stir It Up: Reggae Album Cover Art

118 POPULAR MUSIC GENRES: AN INTRODUCTION Hebdige, D. (1987) Cut 'n' mix: Identity and Caribbean MUSIc. Comedia. CHAPTER 7 S. (1988) Black Culture, White Youth: The Reggae Tradition/romJA to UK. London: Macmillan. Synthpop: into the digital age Morrow, C (1999) StIr It Up: Reggae Album Cover Art. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. Potash, C (1997) Reggae, Rastafarians, Revolution: Jamaican Musicfrom Ska to Dub. London: Music Sales Limited. Stolzoff, N. C (2000) Wake the Town and Tell the People: Dancehall Culture in Jamaica. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press. Recommended listening Antecedents An overview of the genre Various (1989) The Liquidators: Join The Ska Train. In this chapter, we are adopting the term synthpop to deal with an era Various (1998) Trojan Rocksteady Box Set. Trojan. (around 1979-84) and style of music known by several other names. A more widely employed term in pop historiography has been 'New Generic texts Romantic', but this is too narrowly focused on clothing and fashion, Big Youth ( BurI).ing Spear ( and was, as is ever the case, disowned by almost all those supposedly part Alton (1993) Cry Tough. Heartbeat. of the musical 'movement'. The term New Romantic is more usefully King Skitt (1996) Reggae FIre Beat. Jamaican Gold. employed to describe the club scene, subculture and fashion associated K wesi Johnson, Linton (1998) Linton Kwesi Johnson Independam Intavenshan: with certain elements ofearly 1980s' music in Britain. Other terms used to The Island Anthology. Island. describe this genre included 'futurist' and 'peacock punk' (see Rimmer Bob Marley and The Wailers (1972) Catch A Fire. -

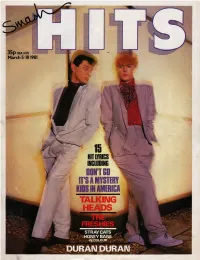

Smash Hits Volume 59

STRAY CATS HOWEYBANE iR^coLoim ^ tHI^^tnJRAN Mws-iiim ^^ Vol. 3 No. 5 TOP SECRET: What To Do In Tho Evont Of A Nuclear Warning Wbila Roading Smash HKs. By Status Quo on Vertigo Records Gathering your personal belongings, Adam Ant posters, toasters, pets, etc., move immediately to the Talking Heads exclusive; there a car will be walthg to I see you everyday walking down the avenue rush you past the Poll Results and Stray Cats colour poster. You will be dropped I'd like to get to know ya, but all I do is smile at you at the corner of the Duran Duran feature where a one-legged match seller will Oh baby, when it comes to talking my tongue gets so tied conduct you to the Honey Bane colour shot on the back page. (He's not as blind But this sidewalk love affair has got me high as a kite as he looks.) Assuming that you can then answer a short series of cjuestions Yeah, yeah, there's something 'bout you baby I like designed to test your knowledge of the latest songwords, news and gossip, you will be allowed to press a concealed button in one of the corners. This button will Well, I'm a slow walker but girl I'd race a mila for you then convert the entire issue into a concrete radiation-proof shelter complete Just to get back in time for my peek-a-boo rendezvous with lawnmower. After memorising the above, kindly eat this page. Well, maybe baby it's the way you wear your blue jeans so tight I can't put my finger on what you're doing right Yeah, yeah, there's something 'bout you baby I like Yeah, yeah, there's something 'bout you baby I Ilk* i SOMETHING -

Copper Cat Books 10 July

Copper Cat Books 10 July Author Title Sub Title Genre 1979 Chevrolet Wiring All Passenger Cars Automotive, Diagrams Reference 400 Notable Americans A compilation of the messages Historical and papers of the presidents A history of Palau Volume One Traditional Palau The First Anthropology, Europeans Regional A Treasure Chest of Children's A Sewing Book From the Ann Hobby Wear Person Collection A Visitor's Guide to Chucalissa Anthropology, Guidebooks, Native Americans Absolutely Effortless rP osperity - Book I Adamantine Threading tools Catalog No 4 Catalogs, Collecting/ Hobbies African Sculpture /The Art History/Study, Brooklyn museum Guidebooks Air Navigation AF Manual 51-40 Volume 1 & 2 Alamogordo Plus Twenty-Five the impact of atomic/energy Historical Years; on science, technology, and world politics. All 21 California Missions Travel U.S. El Camino Real, "The King's Highway" to See All the Missions All Segovia and province America's Test Kitchen The Tv Cookbooks Companion Cookbook 2014 America's Test Kitchen Tv the TV companion cookbook Cookbooks Companion Cookbook 2013 2013 The American Historical Vol 122 No 1 Review The American Historical Vol 121 No 5 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 2 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 5 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 4 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 3 Review The American Revolutionary a Bicentennial collection Historical, Literary Experience, 1776-1976 Collection Amgueddfa Summer/Autumn Bulletin of the National Archaeology 1972 Museum of Wales Los Angeles County Street Guide & Directory. Artes De Mexico No. 102 No 102 Ano XV 1968 Art History/Study Asteroid Ephemerides 1900-2000 Astrology, Copper Cat Books 10 July Author Title Sub Title Genre Astronomy Australia Welcomes You Travel Aviation Magazines Basic Course In Solid-State Reprinted from Machine Engineering / Design Electronics Design Becoming Like God Journal The Belles Heures Of Jean, Duke Of Berry. -

Copper Cat Books 20190809

Copper Cat Books 20190809 Author Title Sub Title Genre 1979 Chevrolet Wiring All Passenger Cars Automotive, Diagrams Reference 400 Notable Americans A compilation of the messages Historical and papers of the presidents A Grandparent's Legacy A history of Palau Volume One Traditional Palau The First Anthropology, Europeans Regional A Treasure Chest of Children's A Sewing Book From the Ann Hobby Wear Person Collection A Visitor's Guide to Chucalissa Anthropology, Guidebooks, Native Americans Absolutely Effortless rP osperity - Book I Adamantine Threading tools Catalog No 4 Catalogs, Collecting/ Hobbies African Sculpture /The Art History/Study, Brooklyn museum Guidebooks Air Navigation AF Manual 51-40 Volume 1 & 2 Alamogordo Plus Twenty-Five the impact of atomic/energy Historical Years; on science, technology, and world politics. All 21 California Missions Travel U.S. El Camino Real, "The King's Highway" to See All the Missions All Segovia and province America's Test Kitchen The Tv Cookbooks Companion Cookbook 2014 America's Test Kitchen Tv the TV companion cookbook Cookbooks Companion Cookbook 2013 2013 The American Historical Vol 122 No 1 Review The American Historical Vol 121 No 5 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 2 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 5 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 4 Review The American Historical Vol 122 No 3 Review The American Revolutionary a Bicentennial collection Historical, Literary Experience, 1776-1976 Collection Amgueddfa Summer/Autumn Bulletin of the National Archaeology 1972 Museum of Wales An Advanced Cathechism Theological Los Angeles County Street Author Title Sub Title Genre Guide & Directory. Antiques on the Cheap, a Savvy Dealer's Tips, Buying, Restoring, Selling Artes De Mexico No. -

Smash Hits Volume 63

35pUSA$l75 April 30 -May 13 1981 GIRLSCHOOL PAULWEILER THE FALL GET ENOUGH THE BANDS PlAY pRYNUMAN^ ADAM ECHO & THE B TEARDROP EX gjGS^ Vol. 3 No. 9 GREY DAY ON STIFF RECORDS THE LARCHES" lay bathed in the warm afternoon sunshine. Peregrine vas on the verandah, sipping a cool drink and dangling his toes in the When I get home it's late at night yping pool. Looking up from the Adam And The Ants colour portrait he I'm black and bloody from my life vatched a butterfly flit lazily from page to page, alighting briefly on the I haven't time to clean my hands ulian Cope feature before shooting off to inspect the Gary Numan Cuts will only sting me through my dreams entrespread. Somewhere in the distance he could hear the Head jardener whistling as he ran a heavy roller over the last part of The Jam It's well past midnight as I lie eries. In a semi-conscious state The only other sound to pierce the drowsy calm came from the back I dream of people fighting me age, where Samantha and Roderick were playing tennis on the Echo And Without any reason I can see he Bunnymen pin-up. Having completed his inspection of The Fall eature. Peregrine yawned and stretched. As Victoria began to rub the Chorus lirst of the tanning lotion into his back, he licked the end of his pencil and In the morning I awake Hon. ifl My arm* my lags my body aches The sky outside is wet and gray So begins another weary day GREY DAY Ma So begins another weary day CROCODILESJflio And Thj Builnymen After eating I go out KEEP OJpfvING YOU REO Speedwagon...|kga....8 People passing by ma shout this IT'SJPNG TO HAPPEN The Undertones....^A,9 I can't stand agony Why don't they talk to ma 1AGNIFICENT FIVE Adam And The Ants 15 the park I have to rest WIUDA TRIANGLE Barry Manilow....... -

Hugh Padgham Discography

JDManagement.com 914.777.7677 Hugh Padgham - Discography updated 09.01.13 P=Produce / E=Engineer / M=Mix / RM=Remix GRAMMYS (4) MOVIE STUDIO / RECORD LABEL ARTIST / COMPOSER / PROGRAM FILM SCORE / ALBUM / TV SHOW CREDIT / NETWORK Sting Ten Summoner's Tales E/M/P A&M Best Engineered Album Phil Collins "Another Day In Paradise" E/M/P Atlantic Record Of The Year Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Album Of The Year Hugh Padgham and Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Producer Of The Year ARTIST ALBUM CREDIT LABEL 2013 Hall and Oates Threads and Grooves M RCA 2012 Adam Ant Playlist: The Very Best of Adam Ant P Epic/Legacy Dominic Miller 5th House M Ais / Q-Rious Music Clannad The Essential Clannad P RCA McFly Memory Lane: The Best of McFly M/P Island 2011 Sting The Best of 25 Years P/E/M Polydor/A&M Records Melissa Etheridge Icon P Island Van der Graaf Generator A Grounding in Numbers M Esoteric Records Various Artists Grandmaster II Project P/E/M Extreme 2010 The Bee Gees Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collections P/E/M Rhino Youssou N'Dour/Peter Gabriel Shakin' The Tree M Virgin Van der Graff Generator A Grounding In Numbers M Virgin Tina Turner Platinum Collection P/E/M Virgin Hall & Oates Collection: H2O, Private Eyes, Voices M RCA Tim Finn Anthology: North South East West P/E/M EMI Music Dist. Mummy Calls Mummy Calls P/E/M Geffen 311 Playlist: The Very Best of 311 P Legacy Various Artists Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P/E/M Sony Various Artists Rock For Amnesty P/E/M Mercury 2009 Tina Turner The Platinum Collection P Virgin Hall & Oates The Collection: H20/Private Eyes/Voices M RCA Bee Gees The Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collection P Rhino Dominic Miller In A Dream P/E/M Independent Lo-Star Closer To The Sun P/E/M Independent Danielle Harmer Superheroes P/E/M EMI Original Soundtrack Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P Sony Music Various Artists Grandmaster Project P/E/M Extreme Various Artists Now, Vol. -

Richardjamesburgessdoctorald

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY: THE EVOLVING ROLE OF THE MUSICIAN RICHARD JAMES BURGESS A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 ii Copyright © 2010 by Richard James Burgess All Rights Reserved ii 1 Structural Change in the Music Industry The Evolving Role of the Musician Abstract The recording industry is little more than one hundred years old. In its short history there have been many changes that have redefined roles, enabled fortunes to be built and caused some to be dissipated. Recording and delivery formats have gone through fundamental conceptual developments and each technological transformation has generated both positive and negative effects. Over the past fifteen years technology has triggered yet another large-scale and protracted revision of the business model, and this adjustment has been exacerbated by two serious economic downturns. This dissertation references the author’s career to provide context and corroboration for the arguments herein. It synthesizes salient constants from more than forty years’ empirical evidence, addresses industry rhetoric and offers methodologies for musicians with examples, analyses, and codifications of relevant elements of the business. The economic asymmetry of the system that exploits musicians’ work can now be rebalanced. Ironically, the technologies that triggered the industry downturn now provide creative entities with mechanisms for redress. This is a propitious time for ontologically reexamining music business realities to determine what is axiological as opposed to simply historical axiom. The primary objective herein is to contribute to the understanding of applied fundamentals, the rules of engagement that enable aspirants and professionals alike to survive and thrive in this dynamic and capricious vocation. -

Vinyl's for Sale, from Richard

Vinyl’s For Sale, from Richard If you are interested in buying any of the below contact me on [email protected] for more info and pictures if you want I try to update monthly as these are on sale else where If you want to check out my feedback and sales on eBay, copy and paste these links cockney1jock Sales http://www.ebay.com/sch/cockney1jock/m.html? _nkw=&_armrs=1&_from=&_ipg=25&_trksid=p3984.m1543.l2654 Feedback http://feedback.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll? ViewFeedback2&userid=cockney1jock&ftab=AllFeedback&sspagename=STRK:MEFSX:FDBK senseisrecords2012 Sales http://www.ebay.com/sch/senseisrecords2012/m.html? _nkw=&_armrs=1&_from=&_ipg=25&_trksid=p3984.m1543.l2654 Feedback http://feedback.ebay.com/ws/eBayISAPI.dll? ViewFeedback2&userid=senseisrecords2012&ftab=AllFeedback&sspagename=STRK:MEFSX:FDBK 10cc Greatest Hits 1972-1978 10cc Live in London Laserdisc 2 x Glass, Plat and Soft Toy Set Book Of 6 x One Piece Demitasse Cups Book Of 3 Tenors In Concert 1994 Laserdisc 3 Tenors In Concert Mehta Laserdisc 44 Magnum Danger #2 ABBA Voulez-Vous #7 ABBA Greatest Hits - 24 #4 ABBA Arrival #10 ABBA Greatest Hits Vol.2 #7 ABBA Greatest Hits Vol.2 #8 ABBA The Album #8 ABBA All About #7 ABBA Slipping Through My Fingers (Coca Cola) #7 ABBA SOS ABBA On And On And On ABBA On And On And On #2 ABBA The Name of the Game ABBA Summer Night City ABBA Eagle ABBA Voulez-Vous #2 7" ABBA Gimme Gimme Gimme #2 ABBA The Winner Takes it All ABBA The Winner Takes it All #2 ABBA Dancing Queen #3 ABBA - Bjorn & Benny She's My Kind of Girl ABC Beauty Stab #2 -

Felix Issue 0572, 1981

Founded in 1949 The Newspaper of Imperial College Union Ex-editor Colin Palmer slams CND movement and NUS in surprise bid for national Tory leadership IMPERIAL COLLEGE delegate, Colin Palmer (last year's FELIX Editor) was one of the three candidates to stand for the post of Chairman of the Federation of Conservative Students at the FCS Conference held at Sheffield University over the Easter vacation. Former Chairmen include Edward Heath, Mark Carlisle and John Biffen. Colin was given a tremendous reception as lie slammed home his speech which is now reprinted below: "As a student journalist I have had to write many reports ol I nion meetings and Conferences but this has been my first FCS Conference. I was shocked at the events that took place in this hall, yesterday. " There was sloppy behaviour from the floor and from the platform. The attitude of the National Committee was poor. Several members casually wandered oil the platform when MPs were speaking. We need to improve the image of the Annual FCS Conference. Now I briefly discuss my views of the XL'S. Those Colleges who have disaffiliated from the NUS should start a new National Union. Other Colleges will be encouraged to disaffiliate as they will at last have the opportunity to be members ol a more representative National Union. "Imperial College is not a member ol the XL'S and I have actively campaigned to keep it out ol NT'S. "We are winning the nuclear debate. Nuclear power can be safely controlled. I believe most people at this conference are pro-nuclear except of course lor those members of the CXI). -

Spandau Ballet

MERCOLEDì 13 GIUGNO 2018 25 milioni di dischi venduti nel mondo, 23 singoli in hit parade e una presenza nelle classifiche britanniche per un totale di oltre 500 settimane. Gli Spandau Ballet, la band esplosa negli anni '80, torna con Spandau Ballet: a ottobre 2018 in una nuova formazione e arriva in Italia per tre incredibili date esclusive: Italia con tre date esclusive a martedì 23 ottobre 2018 a Milano al Fabrique, mercoledì 24 Milano, Roma e Padova ottobre all'Atlantico Live di Roma e giovedì 25 ottobre al Gran Teatro Geox a Padova. Gli Spandau Ballet nascono nel 1979, quando i fratelli Gary e Martin Kamp, il primo bassista e tastierista, il secondo chitarrista del gruppo, formano la band con i loro compagni di scuola John Keeble (batteria) CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Tony Hadley (voce) e Steve Norman (chitarra e sax). Da subito sono capaci di guadagnare grande attenzione e consenso nel panorama musicale londinese, all'epoca in cui il punk sta ormai tramontando, inserendosi nel filone del "New Romantic". "To cut a long story short" è il loro singolo di debutto, il primo di dieci [email protected] brani finiti nella Top 10 del Regno Unito, che subito dopo l'uscita SPETTACOLINEWS.IT nell'autunno 1980 raggiunge la posizione #5 della classifica Inglese. Il brano è seguito dai singoli "The Freeze" e "Musclebound", che si fanno subito strada anche in America. L'anno successivo la band pubblica il suo primo disco registrato in studio "Journeys to Glory"; seguono poco dopo il singolo "Chant n-1", che entra nelle classifiche degli Stati Uniti con il suo ritmo funky e pieno di energia, e il secondo album "Diamond".