Air Transport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aptech Aviation and Learning Academy Shyambazar Centre

APTECH AVIATION AND LEARNING ACADEMY SHYAMBAZAR CENTRE INDUSTRY CONNECT, ALLIANCES & PLACEMENT (ICAP) ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 For queries contact [email protected] / 9831000144 Foreword Aptech Shyambazar ensures that its students get enough guidance to get a job of their choice. The institute has an independent Industry Connect, Alliance and Placement Cell (ICAP) which constantly interacts with the leading recruiters in the corporate world and guides students through their career planning under the guidance and expertise of Aptech Limited. The Industry Connect, Alliance and Placement Cell (ICAP) services include career exploration, skill development, and identification of employment opportunities, job placement and on-going support. Rigorous training and counselling is undertaken regularly to hone on the skills of budding talent and give them the confidence to face the challenges of a corporate world. Imparting theoretical knowledge, developing analytical skills, strengthening communication skills, instilling problem solving and team-work abilities through case studies, research work, presentations etc. are few additional responsibilities of this cell. For queries contact [email protected] / 9831000144 Aptech Aviation and Learning Academy, Shyambazar – The Institute Here are few reasons why you should choose Aptech Aviation & Learning Academy, Shyambazar as your learning hub: Teaching and Management staff are >18 years experienced with the Education Industry Enriched with the latest curriculum Teaching staff is experienced and -

Recent Trend in Indian Air Transport with Reference to Transport Economics and Logistic

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Recent Trend in Indian Air Transport with Reference to Transport Economics and Logistic Dr Vijay Kumar Mishra, Lecturer (Applied Economics), S.J.N.P.G College, Lucknow Air transport is the most modern means of transport which is unmatched by its speed, time- saving and long- distance operation. Air transport is the fastest mode of transport which has reduced distances and converted the world into one unit. But it is also the costliest mode of transport beyond the reach of many people. It is essential for a vast country like India where distances are large and the terrain and climatic conditions so diverse. Through it one can easily reach to remote and inaccessible areas like mountains, forests, deserts etc. It is very useful during the times of war and natural calamities like floods, earthquakes, famines, epidemics, hostility and collapse of law and order. The beginning of the air transport was made in 1911 with a 10 km air mail service between Allahabad and Naini. The real progress was achieved in 1920 when some aerodromes were constructed and the Tata Sons Ltd. started operating internal air services (1922). In 1927 Civil Aviation Department was set up on the recommendation of Air Transport Council. Flying clubs were opened in Delhi, Karachi, Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1928. In 1932 Tata Airways Limited introduced air services between Karachi and Lahore. In 1932, Air India began its journey under the aegis of Tata Airlines, a division of Tata Sons Ltd. -

Liste-Exploitants-Aeronefs.Pdf

EN EN EN COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, XXX C(2009) XXX final COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No xxx/2009 of on the list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006 specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator (Text with EEA relevance) EN EN COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No xxx/2009 of on the list of aircraft operators which performed an aviation activity listed in Annex I to Directive 2003/87/EC on or after 1 January 2006 specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator (Text with EEA relevance) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, Having regard to Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 October 2003 establishing a system for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community and amending Council Directive 96/61/EC1, and in particular Article 18a(3)(a) thereof, Whereas: (1) Directive 2003/87/EC, as amended by Directive 2008/101/EC2, includes aviation activities within the scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community (hereinafter the "Community scheme"). (2) In order to reduce the administrative burden on aircraft operators, Directive 2003/87/EC provides for one Member State to be responsible for each aircraft operator. Article 18a(1) and (2) of Directive 2003/87/EC contains the provisions governing the assignment of each aircraft operator to its administering Member State. The list of aircraft operators and their administering Member States (hereinafter "the list") should ensure that each operator knows which Member State it will be regulated by and that Member States are clear on which operators they should regulate. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH TUESDAY, THE 25 OCTOBER 2016 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 61 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 62 TO 67 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 68 TO 79 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 80 TO 91 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 25.10.2016 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE JAYANT NATH AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS FOR FINAL HEARING ______________________________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 7334/2015 RELIANCE POWER LIMITED & ORS MAHESH AGARWAL,PRADEEP CM APPL. 13473/2015 Vs. UNION OF INDIA & ORS AGGARWAL,SANJEEV NARULA CM APPL. 3686/2016 CM APPL. 8963/2016 PH / AT 2.15 P.M. 25.10.2016 COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MS.JUSTICE SANGITA DHINGRA SEHGAL FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. LPA 560/2016 AJIT SINGH V P RANA CM APPL. 37776/2016 Vs. GOVT OF NCT OF DELHI & CM APPL. 37777/2016 ORS 2. W.P.(C) 5679/2016 MASTER ARJUN ANAND DR. M K GAHLAUT,ASHOK KUMAR Vs. CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION & ANR. AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 3. LPA 835/2015 SANJEEV KUMAR RAJBIR BANSAL & SUNIL CM APPL. 27424/2015 Vs. INDIAN OIL CORPORATION KUMAR,MALA NARAYAN CM APPL. 27426/2015 LTD & ANR 4. LPA 332/2016 CHANCHAL JAIN CHANCHAL JAIN,AMIT Vs. MINES SECRETARY UNION OF MAHAJAN,ARUN KUMAR SRIVASTAVA INDIA & ANR 5. -

Kingfisher Airlines, Spice Jet, Air Deccan and Many More

SUMMER TRAINING REPORT ON Aviation Sector in India “Submitted in the Partial Fulfillment for the Requirement of Post Graduate Diploma in Management” (PGDM) Submitted to: Submitted by: Mr. Sandeep Ranjan Pattnaik Biswanath Panigrahi Marketing and Sales Manager Roll No: 121 At Air Uddan Pvt.ltd (2011-2013) Jagannath International Management School Kalkaji, New Delhi. 1 | P a g e Acknowledgment I have made this project report on “Aviation Sector in India” under the supervision and guidance of Miss Palak Gupta (Internal Mentor) and Mr.Sandeep Ranjan Pattnaik (External Mentor). The special thanks go to my helpful mentors, Miss Palak Gupta and Mr.Sandeep Ranjan Pattnaik. The supervision and support that they gave truly helped the progression and smoothness of the project I have made. The co-operation is much indeed appreciated and enjoyable. Besides, this project report making duration made me realize the value of team work. Name: Biswanath Panigrahi STUDENT’S UNDERTAKING 2 | P a g e I hereby undertake that this is my original work and have never been submitted elsewhere. Project Guide: (By:Biswanath Panigrahi) Mr. Sandeep Ranjan Pattnaik Marketing and Sales Manager Air Uddan Pvt.ltd (EXTERNAL GUIDE) Ms. Palak Gupta (Astt. Professor JIMS) S.NO. CHAPTERS PAGE NO. 01. CHAPTER 1 5 3 | P a g e EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 02. CHAPTER 2 8 COMPANY PROFILE 03. CHAPTER 3 33 Brief history of Indian Aviation sector 04. CHAPTER 4 40 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT 05. CHAPTER 5 43 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 06. CHAPTER 6 46 ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION 07. CHAPTER 7 57 FINDINGS AND INTERFERENCES 08. CHAPTER 8 60 RECOMMENDATION 09. -

Will Trump Presidency Impact Business Aviation?

A SUPPLEMENT TO REGIONAL CONNECTIVITY SCHEME: UDAN LAUNCHED p3 SP’S AVIATION 11/2016 Volume 2 • issue 4 WWW.SPS-AVIATION.COM/BIZAVINDIASUPPLEMENT Pilatus PC-24 made its first public display of the twinjet at the NBAA 2016 PAGE 18 Will Trump Presidency Impact Business Aviation? VIKING TWIN OTTER SERIES 400 : UNMATCHED COMFORT AND VERSATILITY & PERFORMANCE FLEXIBILITY: LINEAGE 1000E P 12 P 15 CABIN ALTITUDE: 3,255 FT* • PASSENGERS: UP TO 19 • PANORAMIC WINDOWS: 14 OPTIMIZED COMFORT Space where you need it. Comfort throughout. The uniquely shaped cabin of the all-new Gulfstream G500™ is optimized to provide plentiful elbow, shoulder and headroom. The bright and quiet interior is filled with 100 percent fresh air pressurized to a cabin altitude lower than any other business jet. And with the new Gulfstream cabin design process that offers abundant cabin configurations, you can create your own masterpiece. For more information, visit gulfstreamg500.com. +91 98 182 95755 | ROHIT KAPUR [email protected] | Gulfstream Authorized Sales Representative TOLL FREE 1800 103 2003 +65 6572 7777 | JASON AKOVENKO [email protected] | Regional Vice President *At the typical initial cruise altitude of 41,000 ft CONTENTS Volume 2 • issue 4 On the cover: According to Ed Bolen NBAA President and CEO. this year’s NBAA-BACE was a resounding success. He said, “The activity level was high, and the enthusiasm was strong. Equally important, the show provided a reminder of the industry’s size and significance in the US and around the world.” -

SP's Airbuz June-July, 2011

SP’s 100.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) ` An Exclusive Magazine on Civil A viation from India www.spsairbuz.net June-July, 2011 green engines INTERVIEW: PRATT & WHITNEY SLEEP ATTACK GENERAL AviatiON SHOW REPOrt: EBACE 2011 AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION RNI NUMBER: DELENG/2008/24198 47 Years of Excellence Personified 6 Aesthetically Noteworthy Publications 2.2 Million Thought-Provoking Releases 25 Million Expert Reports Voicing Industry Concerns …. aspiring beyond excellence. www.spguidepublications.com InsideAdvt A4.indd back Cover_Home second option.indd ad black.indd 1 1 4/30/201017/02/11 1:12:15 11:40 PM AM Fifty percent quieter on-wing. A 75 percent smaller noise footprint on the ground. The Pratt & Whitney PurePower® Geared Turbofan™ engine can easily surpass the most stringent noise regulations. And because it also cuts NOx emissions and reduces CO2 emissions by 3,000 tons per aircraft per year, you can practically hear airlines, airframers and the rest of the planet roar in uncompromising approval. Learn more at PurePowerEngines.com. It’s in our power.™ Compromise_SPs Air Buzz.indd 1 5/9/11 4:05 PM Client: Pratt & Whitney Commercial Engines Ad Title: PurePower - Compromise Publication: SP’s Air Buzz Trim: 210 mm x 267 mm • Bleed: 220 mm x 277 mm • Live: 180 mm x 226 mm Table of Contents SP’s An Exclusive Magazine on Civil A viation from India www.spsairbuz.net May-June, 2011 Cover: 100.00 (INDIA-BASED BUYER ONLY) Airlines have been investing green ` heavily in fuel-efficient engines INTERVIEW: PRATT & WHITNEY SLEEP ATTACK Technology -

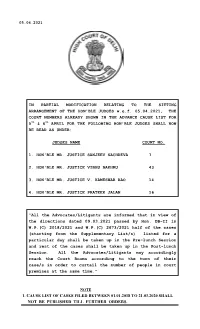

1. Cause List of Cases Filed Between 01.01.2018 to 21.03.2020 Shall Not Be Published Till Further Orders

05.04.2021 IN PARTIAL MODIFICATION RELATING TO THE SITTING ARRANGEMENT OF THE HON'BLE JUDGES w.e.f. 05.04.2021, THE COURT NUMBERS ALREADY SHOWN IN THE ADVANCE CAUSE LIST FOR 5th & 6th APRIL FOR THE FOLLOWING HON'BLE JUDGES SHALL NOW BE READ AS UNDER: JUDGES NAME COURT NO. 1. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJEEV SACHDEVA 7 2. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE VIBHU BAKHRU 43 3. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE V. KAMESWAR RAO 14 4. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PRATEEK JALAN 16 “All the Advocates/Litigants are informed that in view of the directions dated 09.03.2021 passed by Hon. DB-II in W.P.(C) 2018/2021 and W.P.(C) 2673/2021 half of the cases (starting from the Supplementary List/s) listed for a particular day shall be taken up in the Pre-lunch Session and rest of the cases shall be taken up in the Post-lunch Session. All the Advocates/Litigants may accordingly reach the Court Rooms according to the turn of their case/s in order to curtail the number of people in court premises at the same time.” NOTE 1. CAUSE LIST OF CASES FILED BETWEEN 01.01.2018 TO 21.03.2020 SHALL NOT BE PUBLISHED TILL FURTHER ORDERS. HIGH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No. 384/RG/DHC/2020 DATED: 19.3.2021 OFFICE ORDER HON'BLE ADMINISTRATIVE AND GENERAL SUPERVISION COMMITTEE IN ITS MEETING HELD ON 19.03.2021 HAS BEEN PLEASED TO RESOLVE THAT HENCEFORTH THIS COURT SHALL PERMIT HYBRID/VIDEO CONFERENCE HEARING WHERE A REQUEST TO THIS EFFECT IS MADE BY ANY OF THE PARTIES AND/OR THEIR COUNSEL. -

Development of Heritage in Rajasthan Tourism Reservation in Public Sector Undertakings Foreign Investment

79 Written Answers JULY 25. 1996 Written Answers 80 since 1992 7“ 2 3 (c) The Government of Rajasthan has a scheme 3 Continental Aviation 36.83 from 1993 providing for 20% of the eligible capital 4 City Link Airways 0.59 investment or 20 00 lakhs whichever is less for Heritage Hotel projects anywhere in the state of Rajasthan and Cosmos Flights Ltd. 1 55 5 also grant of 25% of the cost of Diesel generating sets 6 Damania Airways 128.39 or Rs.50.000/- whichever is less for Heritage projects 7. Delhi Gulf Airways 0 65 as from 6 6 1994. 8. Elbee Airlines 3 87 (d) There are 30 classified 'Heritage hotels functioning in Rajasthan at present 9. East West Airlines 1 185.06 (e) Under the above scheme, the Government of . Eastern Airways 10 0 10 Rajasthan has so far provided assistance of Rs.19.62 11 Gujarat Airways 2.76 lakhs The Central Government has also released 12 Jet Airways 208 06 Rs 63 15 lakhs under its scheme for Capital and interest subsidy 13 Jagson Airlines 20 84 14. KCV Airlines 0.95 Reservation in Public Sector Undertakings 15 Mals Deoghar Airways 0 32 16 Modiluft Airlines 248.90 1737 SHRI RAM KRIPAL YADAV Will the Minister 17. Megapode Airlines 0 24 of WELFARE be pleased to state 18 NEPC Airlines 113 20 (a) whether it is a fact that the Public Sector Undertakings are not following the recommendations of 19 Raj Aviation 4 59 the Mendal Commission in regard to reservation Sahara India Ltd 143.67 20 (b) if so. -

SP's Aviation June 2011

SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION ED BUYER ONLY) ED BUYER AS -B A NDI I News Flies. We Gather Intelligence. Every Month. From India. 75.00 ( ` Aviationwww.spsaviation.net JUNE • 2011 ENGINE POWERPAGE 18 Regional Aviation FBO Services in India Interview with CAS No Slowdown in Indo-US Relationship LENG/2008/24199 Interview: Pratt & Whitney EBACE 2011 RNI NUMBER: DELENG/2008/24199 DE Show Report Our jets aren’t built tO airline standards. FOr which Our custOmers thank us daily. some manufacturers tout the merits of building business jets to airline standards. we build to an even higher standard: our own. consider the citation mustang. its airframe service life is rated at 37,500 cycles, exceeding that of competing airframes built to “airline standards.” in fact, it’s equivalent to 140 years of typical use. excessive? no. just one of the many ways we go beyond what’s required to do what’s expected of the world’s leading maker of business aircraft. CALL US TODAY. DEMO A CITATION MUSTANG TOMORROW. 000-800-100-3829 | WWW.AvIATOR.CESSNA.COM The Citation MUSTANG Cessna102804 Mustang Airline SP Av.indd 1 12/22/10 12:57 PM BAILEY LAUERMAN Cessna Cessna102804 Mustang Airline SP Av Cessna102804 Pub: SP’s Aviation Color: 4-color Size: Trim 210mm x 267mm, Bleed 277mm x 220mm SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION TABLE of CONTENTS News Flies. We Gather Intelligence. Every Month. From India. AviationIssue 6 • 2011 Dassault Rafale along with EurofighterT yphoon were found 25 Indo-US Relationship compliant with the IAF requirements of a medium multi-role No Slowdown -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

SP's Airbuz Magazine

SP’s Issue 2 • 2008 An Exclusive Magazine on Civil A viation from India GreenThe Enginesare coming • CREW RESOURCE MANAGEMENT • EBACE SHOW REVIEW & MUCH MORE... AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION RNI NUMBER: DELENG/2008/24198 www.spsairbuz.net Commercial Military Powering Innovation. Business, Regional & Helicopter Space Power Generation New Parts Pratt & Whitney delivers the latest technological innovations for the aero- power industry. With 40,000 lbs. of thrust, the F135 for the Lightning II is ™ Worldwide the world’s most powerful fighter engine ever. Our Geared Turbofan engine Service will provide step-change reductions in fuel burn, noise and emissions. Pratt & Whitney. The Eagle is everywhere.™ www.pw.utc.com Table of Contents Cover: ���� �������������� The green engines are coming. ������������������������������� � ������������������ The industry needs to come to terms with the fact that environment issues affecting ����� Cover Story aviation are only going to ��������������������� Environment become more prominent. ���������� ��������������������������� ��������������������� �������������� ������������������������ Green Engines Are Coming Photo: Pratt & Whitney ����������������������������� ����������������� 8 SP's Airbuz_Cover.indd 1 6/4/08 12:24:28 PM AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION SP’s An Exclusive Magazine on Civil A viation from India Technology 17 Fuel Powered by Green 24 Flight Safety Winged Danger Operations 11 AIR CARGO In its Infancy & Raring to Soar BUSINESS AVIATION PRATT & WHITNEY GEARED TURBOFAN ENGINE (GTF) 14 On a Roll, Uphill