The Representation of the American Territory and the Controversy Between Jefferson and Buffon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By: Jim Rosenberger

April 2016 Wisconsin’s Chapter ~ Interested & Involved Number 58 During this time in history: (August 1804 - January 1807) (The source for all entries is, "The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition edited by Gary E. Moulton, U. of Nebraska Press, 1983- 2001.) Our journal entries deal with the activities of Expedition member Sgt. Patrick Gass. August 26, 1804, in today’s Clay County, 1804- - - - - - By: Jim Rosenberger- - - - - -1806 South Dakota, by order of Captains Lewis & Clark: “The commanding officers have In the almost three years that Lewis and Clark lead the Corps of Discovery other thought it proper to appoint Patrick Gass, a events were taking place in the United States and in the world; events they did Sergeant in the Corps of Volunteers for the not know about until their return trip to St. Louis; events that would affect the North Western Discovery, he is therefore to world and our newly formed nation. The Corps had essentially had no news be obeyed and respected accordingly. Sgt. Gass is directed to take charge of the late since leaving St. Louis in May of 1804 but on September 3, 1806 that changed. Sgt. Floyd’s mess and immediately to enter At a location described by Gary Moulton as “…particularly vague…it would on the discharge of such other duties as, by seem to have been in Union County, South Dakota or Dakota County, Nebraska, their previous orders been prescribed for the some miles up the Missouri (River) from present Sioux City…” the men met government of the sergeants of this corps…” two boats coming up the Missouri River. -

PRESERVING FOOD on the TRAIL What Did the Corps of Discovery Do with Its Leftovers?

Lewis in Georgia Company Records Patrick Gass Ludwig and Lewis The Official Publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. August 2001 Volume 27, No. 3 PRESERVING FOOD ON THE TRAIL What did the Corps of Discovery do with its leftovers? THE SALT MAKERS, BY JOHN CLYMER Boiling seawater for salt on the shores of the Pacific, winter 1806. PLUS: JEFFERSON’S WEST, KAREEM HONORS YORK, AND MORE Contents Letters: Chinook Point; John Ordway; iron boat 2 From the Directors: A special thanks to all 4 Bicentennial Report: Ambrose pledges $1 million 5 Preserving Food on the L&C Expedition 6 What the Corps of Discovery did with its leftovers By Leandra Holland Getting Out the Word 12 Preserving food, p. 6 Patrick Gass’s role in publicizing the expedtion’s return By James J. Holmberg Company Books 18 What they tell us about the Corps of Discovery By Bob Moore Lewis’s Georgia Boyhood 25 His brief but formative sojourn in the Deep South By James P. Hendrix, Jr. Trail Notes: Minimizing impact on Lemhi Pass 29 Reviews: Ronda on Jefferson; the Trail by kayak and mule 30 Jefferson, p. 30 L&C Roundup: Kareem honors York; Chapter News 33 From the Library: New librarian sought 34 Soundings 36 A Lewis & Clark Symphony? By Skip Jackson On the cover We chose The Salt Makers, John Clymer’s dramatic painting of Lewis and Clark’s men making salt under the curious gaze of Pacific Coast Indians, to illustrate Leandra Holland’s story on food preservation (pages 6-11). -

Madison County Marriages

Volume 19, Issue 2 The Madison County, Florida Genealogical News Apr – Sep 2014 The Madison County, Florida Genealogical News Volume 19, Issue 2 Apr - Sep, 2014 P. O. Box 136 ISSN: 1087-7746 Madison, FL 32341-0136 33 Volume 19, Issue 2 The Madison County, Florida Genealogical News Apr – Sep 2014 Table of Contents Upcoming 2014/2015 Genealogy Conferences ................................................................................................. 34 Extracts from the New Enterprise, Madison, FL, Apr 1905 .......................................................................... 35 Circus Biography, Mattie Lee Price ......................................................................................................................... 40 Francis Eppes (1865-1929) ........................................................................................................................................ 42 Death of a Grandson of Jefferson .............................................................................................................................. 43 Boston Cemetery, Boston, Thomas County, Georgia ....................................................................................... 44 How Well do you Understand Family Terminology? ..................................................................................... 44 Shorter College ................................................................................................................................................................. 47 Extracts from Madison County -

Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 5 Number 2 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 5, Article 7 Issue 2 1926 Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida Nicholas Ware Eppes Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Eppes, Nicholas Ware (1926) "Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol5/iss2/7 Eppes: Francis Eppes (1801-1881), Pioneer of Florida 94 FRANCIS EPPES (1801-1881), PIONEER OF FLORIDA In the White House, in Washington, in the year 1801, Thomas Jefferson waited anxiously for tidings from Monticello ; for there his beloved daughter, the beautiful Maria Jefferson Eppes, was waging the world-old battle for life. For hours the great states- man had been walking the floor, too miserable for sleep. Then came a knock at the door and Peter handed him a scrap of paper on which was hurriedly scrawled these words, “Mother and boy doing well- a fine hearty youngster, with hazel eyes and to his mother’s delight he has hair like your own. She sends dear love to the Father she is longing to see.” The night was almost over and Thomas Jefferson, after a prayer of thanksgiving, slept soundly. Two happy years passed for this devoted family and then Mrs. -

Corps of Discovery-Lewis and Clark

Corps of Discovery-Lewis and Clark General Grade Level Middle School Author Info Marsha Klosterman Siuslaw Middle School Florence, OR Type of Lesson Document Analysis Duration 2 class periods Interdisciplinary Connections Reading content for information Writing Objectives Overview Students will read Jefferson’s letter to Congress and his letter of instructions to Meriwether Lewis. By skimming for information and answering questions about their reading, they will gain an understanding of events surrounding the planning of the expedition. They will better understand Jefferson’s forward thinking. Prior Knowledge Students should understand the historic background of the Louisiana Territory to understand why the United States wanted to control it. State Standards Oregon State Standards: SS.08.06.02 Trace the route and understand the significance of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. SS.08.SA.01 Clarify key aspects of an event, issue, or problem through inquiry and research. Objectives/Learning Outcomes Students will understand Jefferson’s method of funding the Corps of Discovery Students will understand the goals Jefferson had for Lewis and Clark to accomplish. They will also understand how he was looking forward into the future of the U.S. Students will discover what it takes to outfit such an expedition. Technology Connections/outcomes The lesson can connect to geography, native studies, some math, and reading for understanding and writing. Additional Learning Outcomes Students will answer questons about materials. Essential Questions 1. How much did Jefferson request from Congress to fund the expedition? How much did the expedtition end up costing? 2. Name at least 3 goals of the expedition. -

Analyzing Primary Source Documents to Understand U.S. Expansionism and 19Th Century U.S.-Indian Relations

CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS | UPDATED FALL 2019 54 High School Lesson Analyzing Primary Source Documents to Understand U.S. Expansionism and 19th Century U.S.-Indian Relations Rationale The purpose of this unit is to increase awareness among students about the impact of the Lewis and Clark expedition and westward expansion on the lives of Native Americans. During this investigation, students analyze the letters and speeches of Thomas Jefferson in order to gain an understanding of U.S. objectives for the Lewis and Clark expedition, U.S.-Indian relations and plans for U.S. expansion. Readings about the Doctrine of Discovery and Manifest Destiny extend student learning about the religious and political underpinnings of expansionism. Students are presented with the perspectives of contemporary Native Americans through a speech by Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation and a song by a Cherokee rap artist, and engage in a research project to learn more about contemporary native culture and issues. Objectives Students will increase awareness of the impact of the Lewis and Clark expedition on the lives of Native Americans. Students will analyze primary documents and other texts in order to learn about U.S. expansionism and 19th century U.S.-Indian relations. Students will consider the perspectives of contemporary Native American leaders. Key Words Students will conduct research about contemporary native culture and issues. Bicentennial Commerce Age Range Contemporary Grades 11–12 Doctrine of Discovery Objective Expedition Time Exploitation 1½–2 -

Grade 05 Social Studies Unit 07 Exemplar Lesson 01: Explore to Expand

Grade 5 Social Studies Unit: 07 Lesson: 01 Suggested Duration: 5 days Grade 05 Social Studies Unit 07 Exemplar Lesson 01: Explore to Expand This lesson is one approach to teaching the State Standards associated with this unit. Districts are encouraged to customize this lesson by supplementing with district-approved resources, materials, and activities to best meet the needs of learners. The duration for this lesson is only a recommendation, and districts may modify the time frame to meet students’ needs. To better understand how your district may be implementing CSCOPE lessons, please contact your child’s teacher. (For your convenience, please find linked the TEA Commissioner’s List of State Board of Education Approved Instructional Resources and Midcycle State Adopted Instructional Materials.) Lesson Synopsis Students learn about the Louisiana Purchase and the expedition led by Lewis and Clark called the Corps of Discovery. Students learn the importance of decision making and problem solving in leadership, as they learn the valuable contributions made by the Corps of Discovery. TEKS The Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) listed below are the standards adopted by the State Board of Education, which are required by Texas law. Any standard that has a strike-through (e.g. sample phrase) indicates that portion of the standard is taught in a previous or subsequent unit. The TEKS are available on the Texas Education Agency website at http://www.tea.state.tx.us/index2.aspx?id=6148. 5.4 History. The student understands political, economic, and social changes that occurred in the United States during the 19th century. -

116 STAT. 3278 PROCLAMATION 7575-Jljne 28, 2002 Lewis and Clark Bicentennial

116 STAT. 3278 PROCLAMATION 7575-JlJNE 28, 2002 Proclamation 7575 of June 28, 2002 Lewis and Clark Bicentennial By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Nearly 200 years ago, President Thomas Jefferson sent an expedition westward to find and map a transcontinental water route to the Pacific Ocean. With approval from the Congress, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark embarked on their legendary 3-year journey to ex plore the uncharted West. The expedition included 33 permanent party members, known as the Corps of Discovery. Their effort to chart the area between the Missouri River and the Pa cific Coast set these courageous Americans on a remarkable scientific voyage that changed our Nation. In successfully completing the over land journey between the Missouri and Columbia River systems, they opened the unknown West for future development. During their explo ration, Lewis and Clark collected plant and animal specimens, studied Indian cultures, conducted diplomatic councils, established trading re lationships with tribes, and recorded weather data. To accomplish their goals, the Corps of Discovery relied on the assistance and guidance of Sakajawea, a Shoshone Indian woman. As we approach the 200th aimiversary of Lewis and Clark's expedition, we commend their resourcefulness, determination, and bravery. This Bicentennial should also serve to remind us of our Nation's outstand ing natural resources. Many of these treasures first detailed by Lewis and Clark are available today for people to visit, study, and enjoy. As the commemoration of this journey begins in 2003, I encourage all Americans to celebrate the accomplishments of Lewis and Clark and to recognize their contributions to our history. -

Jeffersonian Racism

MALTE HINRICHSEN JEFFERSONIAN RACISM JEFFERSONIAN RACISM Universität Hamburg Fakultät für Wirtschafts - und Sozialwissenschaften Dissertation Zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Wirtschafts - und Sozialwissenschaften »Dr. phil.« (gemäß der Promotionsordnung v o m 2 4 . A u g u s t 2 0 1 0 ) vorgelegt von Malte Hinrichsen aus Bremerhaven Hamburg, den 15. August 2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Wulf D. Hund Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Olaf Asbach Datum der Disputation: 16. Mai 2017 - CONTENTS - I. Introduction: Studying Jeffersonian Racism 1 II. The History of Jeffersonian Racism 25 1. ›Cushioned by Slavery‹ – Colonial Virginia 30 1.1 Jefferson and his Ancestors 32 1.2 Jefferson and his Early Life 45 2. ›Weaver of the National Tale‹ – Revolutionary America 61 2.1 Jefferson and the American Revolution 62 2.2 Jefferson and the Enlightenment 77 3. ›Rising Tide of Racism‹ – Early Republic 97 3.1 Jefferson and Rebellious Slaves 98 3.2 Jefferson and Westward Expansion 118 III. The Scope of Jeffersonian Racism 139 4. ›Race, Class, and Legal Status‹ – Jefferson and Slavery 149 4.1 Racism and the Slave Plantation 159 4.2 Racism and American Slavery 188 5. ›People plus Land‹ – Jefferson and the United States 211 5.1 Racism and Empire 218 5.2 Racism and National Identity 239 6. ›The Prevailing Perplexity‹ – Jefferson and Science 258 6.1 Racism and Nature 266 6.2 Racism and History 283 IV. Conclusion: Jeffersonian Racism and ›Presentism‹ 303 Acknowledgements 315 Bibliography 317 Appendix 357 I. Introduction: Studying Jeffersonian Racism »Off His Pedestal«, The Atlantic Monthly headlined in October 1996, illustrating the bold claim with a bust of Thomas Jefferson being hammered to the floor. -

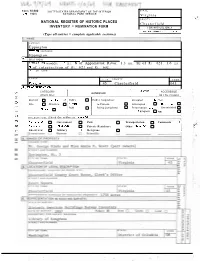

Nomination Form for Nps Use Only

STATE: Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Doc. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Chesterfield INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Eppington AND/OR HISTORIC: Epping ton I2, LOCATION P.......,, ~'TREET NUMBER: .7 mi. N of Appomattox River, 1.3 mi. SE of Rt. 621, 1.6 mi. S of intersection of Rt. 621 and Rt. 602. CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE Vir~inia 45 Chesterfield 041 CLASSIFICATION -..., .. CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Building Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Q Yes: Site Structure Private In Process Unoccupied Restrlcted Both Being Considered Preservation work Unrestricted Obiect In progress N,,, PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Approprlale) Agricultural Government Park Transportation Comments a Cornrnerciol Industrial Private Residence Other (specrfy) Educational Military D Religious (Check 0"s) cONO'TiON Exceile;l,;, ;"e'one) Fair Oaterioroted Ruin, U Unexposed 1 1 (Check 0"s) INTEGRITY un~ltwed MOV-~ 0 Originel sits DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (Ifknown) PHYSICAL APPEhRINCE Eppington ffawes a three-bay, two-and-a-half story central block with hipped roof, dormers, modillioned cornice, and flanking one-story wings. The first floor front of the central block has been altered by board and batten siding and a rather dcep, full-length porch. ThecentralU.eck is framed with two tall exterior end chimneys which rise from the roof of the wings. The roofline of the wings terminates in a low-pitched hip which softens the effect of the rather.steeply pitched roof of the central block. -

Thomas Jefferson, Congress, and the Gunboat Debate, 1802

IN SEARCH OF A MORE REPUBLICAN NAVAL DEFENSE: THOMAS JEFFERSON, CONGRESS, AND THE GUNBOAT DEBATE, 1802-1810 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty and Department of History Liberty University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History By Ethan Zook December, 2019 1 Acknowledgements I was introduced to Thomas Jefferson in 2003, the two hundredth anniversary of the Lewis and Clark expedition. I was a member of a high school group which traced the route of the Corps of Discovery across the United States; we read Jefferson’s papers and considered themes like empire building and republicanism. That summer was my first encounter with his thought, and I was hooked. I’m grateful to Myron Blosser and Elwood Yoder, my high school teachers from Eastern Mennonite High School, who started my quest to better understand Jefferson. I’m also thankful for the assistance of scholars who graciously provided materials and suggestions. Craig L. Symonds, author of Navalists and Antinavalists, kindly (and completely unexpectedly) responded to my “out of the blue” email with encouragement and suggestions. Gene A. Smith assisted my search for a copy of his book For the Purposes of Defense. Christopher R. Sabick, Archaeological Director at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum, provided a copy of Eric Emery’s archeological survey of the gunboat USS Allen. I’m especially grateful to my thesis advisors Troy L. Kickler and Carey M. Roberts who guided me through the research and writing process with extraordinary patience, and to David J. White who provided thoughtful suggestions for the later drafts. -

Telling the Story: Changing Perceptions of the Lewis and Clark Journals

TELLING THE STORY: CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF THE LEWIS AND CLARK JOURNALS by Deborah Malony Dukes A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Science Emphasis: Teaching American History May 2006 TELLING THE STORY: CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF THE LEWIS AND CLARK JOURNALS by Deborah Malony Dukes Approved by the Master’s Thesis Committee: Delores McBroome, Major Professor Date Gayle Olson-Raymer, Committee Member Date Rodney Sievers, Committee Member Date Delores McBroome, Graduate Coordinator Date Donna E. Schafer, Dean for Research and Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT The collective journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition have been objects of fascination and interpretation ever since the Corps of Discovery’s homecoming in 1806. Despite President Thomas Jefferson’s direction that Meriwether Lewis prepare the journals for publication, Lewis’ untimely death in 1809 left the editing of the expedition’s records – and much of the storytelling – to a series of writers and editors of varying interests, abilities and degrees of integrity. Understandably the several major editions and many other versions of the story have reflected the lives and times of the editors. For instance, ornithologist Elliott Coues was the first – 89 years after the fact – to acknowledge the expedition’s many scientific and ethnological observations. For their own purposes, successive generations of activists have appropriated iconic expedition members, emphasized or even invented anecdotes, and supposed discoveries. Scholarly and public interest in the journals has peaked during this bicentennial period, as often happens around the times of major anniversaries of the expedition.