Public Transport Integration: the Case Study of Thessaloniki, Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Podzemne Željeznice U Prometnim Sustavima Gradova

Podzemne željeznice u prometnim sustavima gradova Lesi, Dalibor Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Fakultet prometnih znanosti Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:119:523020 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-04 Repository / Repozitorij: Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences - Institutional Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FAKULTET PROMETNIH ZNANOSTI DALIBOR LESI PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA DIPLOMSKI RAD Zagreb, 2017. Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet prometnih znanosti DIPLOMSKI RAD PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA SUBWAYS IN THE TRANSPORT SYSTEMS OF CITIES Mentor: doc.dr.sc.Mladen Nikšić Student: Dalibor Lesi JMBAG: 0135221919 Zagreb, 2017. Sažetak Gradovi Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne i Liverpool su europski gradovi sa različitim sustavom podzemne željeznice čiji razvoj odgovara ekonomskoj situaciji gradskih središta. Trenutno stanje pojedinih podzemno željeznićkih sustava i njihova primjenjena tehnologija uvelike odražava stanje razvoja javnog gradskog prijevoza i mreže javnog gradskog prometa. Svaki od prijevoznika u podzemnim željeznicama u tim gradovima ima različiti tehnički pristup obavljanja javnog gradskog prijevoza te korištenjem optimalnim brojem motornih prijevoznih jedinica osigurava zadovoljenje potreba javnog gradskog i metropolitanskog područja grada. Kroz usporedbu tehničkih podataka pojedinih podzemnih željeznica može se uvidjeti i zaključiti koji od sustava podzemnih željeznica je veći i koje oblike tehničkih rješenja koristi. Ključne riječi: Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne, Liverpool, podzemna željeznica, javni gradski prijevoz, linija, tip vlaka, tvrtka, prihod, cijena. Summary Cities Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne and Liverpool are european cities with different metro system by wich development reflects economic situation of city areas. -

IINFORMATION for the DISABLED Disclaimer

Embassy of the United States of America Athens, Greece October 2013 IINFORMATION FOR THE DISABLED Disclaimer: The following information is presented so that you have an understanding of the facilities, laws and procedures currently in force. For official and authoritative information, please consult directly with the relevant authorities as described below. Your flight to Greece: Disabled passengers and passengers with limited mobility are encouraged to notify the air carrier/tour operator of the type of assistance needed at least 48 hours before the flight departure. Athens International Airport facilities for the disabled include parking spaces, wheelchair ramps, a special walkway for people with impaired vision, elevators with Braille floor-selection buttons, etc. For detailed information on services for disabled passengers and passengers with limited mobility, please visit the airport’s website, www.aia.gr Hellenic Railways Organization (O.S.E.): In Athens, the railway office for persons with disabilities is at Larissa main station. Open from 6 AM to midnight, it can be reached at tel.: 210-529-8838, in Thessaloniki at tel.: 2310-59-9071. Information on itineraries, fares and special services provided by the O.S.E. is available at: http://www.ose.gr. Recorded train schedule information can be obtained via Telephone number 1110. Ferries: The Greek Ministry of Merchant Marine reports most ferry companies offer accessibility and facilities for people with disabilities and has posted a list of companies on its website, www.yen.gr. For information concerning ferry schedules, please consult www.gtp.gr Athens Metro: Metro service connects Athens International Airport directly with city center. -

Athens Metro Athens Metro

ATHENSATHENS METROMETRO Past,Past, PresentPresent && FutureFuture Dr. G. Leoutsakos ATTIKO METRO S.A. 46th ECCE Meeting Athens, 19 October 2007 ATHENS METRO LINES HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS METRO NETWORK PHASES Line 1 (26 km, 23 stations, 1 depot, 220 train cars) Base Project (17.5 km, 20 stations, 1 depot, 168 train cars) [2000] First phase extensions (8.7 km, 4 stations, 1 depot, 126 train cars) [2004] + airport link 20.9 km, 4 stations (shared with Suburban Rail) [2004] + 4.3 km, 3 stations [2007] Extensions under construction (8.5 km, 10 stations, 2 depots, 102 train cars) [2008-2010] Extensions under tender (8.2 km, 7 stations) [2013] New line 4 (21 km, 20 stations, 1 depot, 180 train cars) [2020] LINE 1 – ISAP 9 26 km long 9 24 stations 9 3.1 km of underground line 9 In operation since 1869 9 450,000 passengers/day LENGTH BASE PROJECT STATIONS (km) Line 2 Sepolia – Dafni 9.2 12 BASE PROJECT Monastirakiι – Ethniki Line 3 8.4 8 Amyna TOTAL 17.6 20 HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS LENGTH PROJECTS IN OPERATION STATIONS (km.) PROJECTS IN Line 2 Ag. Antonios – Ag. Dimitrios 30.4 27 Line 3 Egaleo – Doukissis Plakentias OPERATION Doukissis Plakentias – Αirport Line 3 (Suburban Line in common 20.7 4 use with the Metro) TOTAL 51.1 31 HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS -

Athens, Greece Smarter Cities Challenge Report

Athens, Greece Smarter Cities Challenge report Contents 1. Executive summary 2 2. Introduction 5 A. The IBM Smarter Cities Challenge 5 B. The challenge 7 3. Findings, context, approach and roadmap 8 A. Findings, context and approach 8 B. Roadmap 10 4. Recommendations 12 1. Strengthen regulation enforcement in the city centre 12 Recommendation 1.1: Use technology to strengthen enforcement 15 Recommendation 1.2: Make it easier for people to adhere to regulations 19 2. Develop a comprehensive multimodal transportation strategy 21 Recommendation 2.1: Define and ensure compliance with rules on parking for tourist buses 22 Recommendation 2.2: Improve pedestrian streets and prioritise additional streets for conversion 24 Recommendation 2.3: Establish a long-term strategy to reduce the use of cars 30 3. Deploy intelligent transportation technology 32 Recommendation 3.1: Deploy an Operations Centre to aggregate data and to monitor and coordinate mobility for Attica 35 Recommendation 3.2: Redeploy and upgrade the Regional Traffic Management System 38 Recommendation 3.3: Deploy video analytics system 42 4. Cultivate public and private information sharing 44 Recommendation 4.1: Engage public and private businesses and citizens in cooperation through Open Data 46 Recommendation 4.2: Engage with inter-agency stakeholders to enable real-time information hub 47 5. Engage Athenians on the transportation vision through multimedia 48 Recommendation 5: Launch a campaign to engage the public to help reduce congestion and reclaim public spaces 52 6. Set the foundation for a Metropolitan Transportation Authority 53 Recommendation 6: Align governance with goals 58 5. Conclusion 59 6. Appendix 60 A. -

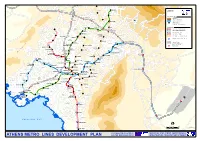

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Infrastructure, Transport and Networks

AHARNAE Kifissia M t . P ANO Lykovrysi KIFISSIA e LIOSIA Zefyrion n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT OPERATING LINES METAMORFOSI Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1, ISAP IRAKLIO Melissia LINE 2, ATTIKO METRO LIKOTRIPA LINE 3, ATTIKO METRO Kamatero MAROUSSI METRO STATION Iraklio FUTURE METRO STATION, ISAP Penteli IRAKLIO NERATZIOTISSA OTE EXTENSIONS Nea Filadelfia LINE 2, UNDER CONSTRUCTION KIFISSIAS NEA Maroussi LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli IONIA LINE 3, TENDERED OUT Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Ionia Aghioi OLYMPIAKO PENTELIS LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN & TENDERING AG.ANARGIRI Anargyri STADIO PERISSOS Nea "®P PARKING FACILITY - ATTIKO METRO Halkidona SIDERA DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa Suburban Railway Kallitechnoupoli ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei Halandri "®P o ®P Suburban Railway Section " Also Used By Attiko Metro e AGHIOS HALANDRI l "®P ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Railway Station a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI . PATISSIA GALATSI Aghia Peristeri THIMARAKIA P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini NIKOLAOS ANTONIOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P ATHENS KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera PANEPISTIMIO KERAMIKOS "®P MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS ZOGRAFOU THISSIO EVANGELISMOS Zografou Nikea ROUF SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios KESSARIANI PAGRATI Ioannis ACROPOLI Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani RENTIS SYGROU-FIX P KALITHEA TAVROS "® NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS LEFKA Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSHATO IOANNIS o Peania Dafni t KAMINIA Moshato Ymittos Kallithea t Drapetsona PIRAEUS DAFNI i FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

INVITATION International Technical Seminar with Grand Master Prof

INVITATION International Technical Seminar with Grand Master Prof. Hwang Ho Yong A.C. Taekwon-Do Polichnis, with the approval of the Athletic Taekwon-do Federation of Hellas, organizes an INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL SEMINAR conducted by Grand Master Prof. Hwang Ho Yong on 7-9 December 2018. Grand Master Professor’s Hwang short resume Grand Master, Professor Hwang Ho Yong Senior Vice President of the International Taekwon-do Federation and Technical and Education Committee Chairman, was born on 11/05/1956 in Sin Uiz of Korea. From 1983 until 1986 he was a member of the demonstration team of the International Taekwon-do Federation which made demos almost throughout the world (China, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Norway, Poland, Singapore, India, etc. ..) in an efort to make known the Taekwon-do around the world. In 1987 he was sent by the International Taekwon-do Federation to Czechoslovakia to teach Taekwon-do. Under his guidance, the Czech Taekwon-do Federation became a very strong and well organized NGB. In 2011, 7th of September, he earned 9th DAN and became the 1st Korean 9th DAN holder (K-9-1). He was Chairman of the ITF Junior Committee and then the Education committee. Since 2008 is Chairman of the ITF Technical Committee and subsequently by the merger of the two committees into one, he is the Chairman of the Technical and Education Committee of the ITF. His job is the spread of Taekwon-do around the world and the unifcation of educational methods by all instructors, as well as the preservation of genuine art of Taekwondo. He teaches and directs systematically Taekwon-do in Poland, Hungary, Switzerland, Netherlands and Slovakia. -

Zitron Metro References

1 of 20 ZITRON METRO REFERENCES No. Project Client Contractor Fan Type Qty Country Year 1 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID FLATTER ZVM 1-12-18,5/6 28 SPAIN 1997 2 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVM 1-12-18,5/6 30 SPAIN 1997 3 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVP 1-12-18,5/6 -3,7/12 + ZVM 1-18-30/8 10 SPAIN 1997 4 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVP 1-12-18,5/6 -3,7/12 + ZVM 1-18-30/8 10 SPAIN 1997 5 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 6 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 7 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 8 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 9 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 10 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 11 LINEA 11 METRO MADRID ELECNOR ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-14-23/6-4,5/12 10 SPAIN 1998 12 LINEA 11 METRO MADRID ELECNOR ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-14-23/6-4,5/12 10 SPAIN 1998 13 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. -

Extreme Weather

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com MAY 2017 NO. 953 KEEPING RUNNING IN EXTREME WEATHER Los Angeles: Measure M funding boosts LRT expansion Terror targets the St Petersburg Metro US draft budget freezes out transit 14 hurt as Hong Kong tram overturns UK tram-train Chaos theory 05> £4.40 Under scrutiny yet Making sense of the looking to 2018 Charleroi Metro 9 771460 832050 Phil Long “A great event, really well organised and the dinner, reception and exhibition space made for great networking time.” Andy Byford – CEO, Toronto Transit Commission MANCHESTER “I really enjoyed the conference and made some helpful contacts. Thanks for bringing such a professional event together.” 18-19 July 2017 Will Marshall – Siemens Mobility USA Topics and themes for 2017 include: > Rewriting the business case for light rail investment > Cyber security – Responsibilities and safeguards > Models for procurement and resourcing strategies > Safety and security: Anti-vandalism measures > Putting light rail at the heart of the community > Digitisation and real-time monitoring > Street-running safety challenges > Managing obsolescence > Next-generation driver aids > Wire-free solutions > Are we delivering the best passenger environments? > Composite and materials technologies > From smartcard to smartphone ticketing > Rail and trackform innovation > Traction energy optimisation and efficiency > Major project updates Confirmed speakers include: > Paolo Carbone – Head of Public Transport Capital Programmes, Transport Infrastructure Ireland > Geoff Inskip – Chairman, UKTram > Jane Cole – Managing Director, Blackpool Transport > Allan Alaküla – Head of Tallinn EU Office, City of Tallinn > Andres Muñoz de Dios – Director General, MetroTenerife > Tobyn Hughes – Managing Director (Transport Operations), North East Combined Authority > Alejandro Moreno – Alliance Director, Midland Metro Alliance > Ana M. -

Wastewater and Stormwater Infrastructures of Thessaloniki City, Hellas, Through Centuries

Water Utility Journal 16: 117-129, 2017. © 2017 E.W. Publications Wastewater and stormwater infrastructures of Thessaloniki city, Hellas, through centuries S. Yannopoulos1*, A. Kaiafa-Saropoulou2, E. Gala-Georgila3, E. Eleftheriadou4 and A.N. Angelakis5 1 School of Rural and Surveying Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece 2 School of Architecture, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece, Cherianon 7, Kalamaria, 55133, Thessaloniki, Greece 3 Delfon 195, 54655 Thessaloniki, Greece 4 Department of Environmental Inspectory of Northern Greece, Ministry of Environment and Energy, Adrianoupoleos 24, 551 33, Thessaloniki, Greece 5 Institute of Iraklion, National Foundation for Agricultural Research (N.AG.RE.F.), 71307 Iraklion, Greece * e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The city of Thessaloniki was founded on the east coast of Thermaikos Gulf, by King Kassandros in 315 BC, according to the Hippodamian urban plan. Since its foundation, the city was bounded by stone built fortification, which remained immovable through the centuries. Within it, the urban aspect changed many times. The city developed outside the walls in modern times. There is no doubt that hydraulic infrastructure were main elements of the urban environment. Thus, apart from the aqueducts of the city and in parallel with the water distribution networks, the city had also an advanced waste and rain water system under the urban grid, which was evolved according to the local hydrogeological data and was planned simultaneously with the roads’ and buildings’ construction. Furthermore, it was associated with the gradual rising of the population, political and economic conditions in each period, so as with the level of culture and technology. -

Urban Heat Island in Thessaloniki City, Greece: a Geospatial Analysis

Urban heat island in Thessaloniki city, Greece: a geospatial analysis Ourania Eftychiadou SID: 3304150003 SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Energy Building Design OCTOBER 2017 THESSALONIKI – GREECE -i- Urban heat island in Thessaloniki city, Greece: a geospatial analysis Student Name Ourania Eftychiadou SID: 3304150003 Supervisor: Prof. Dionysia Kolokotsa Supervising Committee Prof. Agis Papadopoulos Members: Dr. Georgios Martinopoulos SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Energy Building Design OCTOBER 2017 THESSALONIKI – GREECE -ii- «10.8.1986 Ἀληθινό εἶναι ὅ,τι τό ξαναβρίσκουμε γιατί μᾶς χρειάζεται» (Κωνσταντινίδης Α., «Η Αρχιτεκτονική της Αρχιτεκτονικής», 2004:267) -iii- Abstract The present master thesis discusses the issue of urban heat island in Thessaloniki city, in Greece, using a geospatial approach to the analysis of the phenomenon. The UHI phenomenon is known almost from the beginning of cities’ urbanization. What encourages scientists in a global scale to select it as a study subject is that, the phenomenon becomes more pronounced at these years due to climate change and strong urbanization on a global scale. At the same time, there is a keen interest in the quality of peoples’ life in cities in relation to environmental and energy issues that are directly connected to the environment protection and the conservation of natural resources. Thessaloniki is a big city for Greece and a reference point for the Balkan space but for this work is the field of the UHI phenomenon research. The study was conducted using air temperatures and applying the Kriging Ordinary interpolation technique in ArcGIS. -

The World of Metro Rail in Pictures

THE WORLD OF METRO RAIL IN PICTURES "Dragon Boat Architecture" at Jiantan Metro Station, Taipei, Taiwan By Dr. F.A. Wingler, Germany, July 2020 Dr. Frank August Wingler Doenhoffstrasse 92 D 51373 Leverkusen [email protected] http://www.drwingler.com - b - 21st Century Global Metro Rail in Pictures This is Part II of a Gallery with Pictures of 21st Century Global Metro Rail, with exception of Indian Metro Rail (Part I), elaborated for a book project of the authors M.M. Agarwal, S. Chandra and K.K. Miglani on METRO RAIL IN INDIA . Metros across the World have been in operation since the late 1800s and transport millions of commuters across cities every day. There are now more than 190 Metro Installations globally with an average of about 190 million daily passengers. The first Metro Rail, that went underground, had been in London, England, and opened as an underground steam train for the public on 10st January 1863: llustration of a Train at Praed Street Junction near Paddington, 1863; from: History Today, Volume 63, Issue 1, January, 2013 Vintage London Underground Steam Train; Source “Made up in Britain” 1 Thed worl over, the 21st Century observed the opening of many new Metro Lines, the extension o f existing Metro Systems and the acquisition of modern Rolling Stocks, mostly in Asian Countries. In the last decades Urban Rail Transits in China developed fastest in the world. Urban Rail Transit in the People's Republic of China encompasses a broad range of urban and suburban electric passenger rail mass transit systems including subway, light rail, tram and maglev. -

Assessing Biofilm Development in Drinking Water Distribution Systems

Universitat Politecnica` de Valencia` Doctoral Thesis Assessing Biofilm Development in Drinking Water Distribution Systems by Machine Learning Methods Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Rafael Perez´ Garc´ıa Prof. Dr. Joaqu´ın Izquierdo Sebastian´ Author: Universitat Polit`ecnicade Val`encia Eva Ramos Mart´ınez Dr. Manuel Herrera Fernandez´ University of Bath A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Water and Environmental Engineering in the FluIng Multidisciplinary Research Group Institute for Multidisciplinary Mathematics Department of Hydraulic and Environmental Engineering 18th April 2016 Declaration of Authorship I, Eva Ramos Mart´ınez, declare that this thesis titled, 'Assessing Biofilm Development in Drinking Water Distribution Systems by Machine Learning Methods' and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for a research degree at this University. Where any part of this thesis has previously been submitted for a degree or any other qualification at this University or any other institution, this has been clearly stated. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attrib- uted. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Where the thesis is based on work done by myself jointly with others, I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. Signed: Date: i \It's not the critic who counts. It's not the person who points out how the person who's actually doing things is doing them wrong or messing up.