Archives of Economic History Apxeion Oikonomikh™ I™Topia™

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Podzemne Željeznice U Prometnim Sustavima Gradova

Podzemne željeznice u prometnim sustavima gradova Lesi, Dalibor Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Fakultet prometnih znanosti Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:119:523020 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-04 Repository / Repozitorij: Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences - Institutional Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FAKULTET PROMETNIH ZNANOSTI DALIBOR LESI PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA DIPLOMSKI RAD Zagreb, 2017. Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet prometnih znanosti DIPLOMSKI RAD PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA SUBWAYS IN THE TRANSPORT SYSTEMS OF CITIES Mentor: doc.dr.sc.Mladen Nikšić Student: Dalibor Lesi JMBAG: 0135221919 Zagreb, 2017. Sažetak Gradovi Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne i Liverpool su europski gradovi sa različitim sustavom podzemne željeznice čiji razvoj odgovara ekonomskoj situaciji gradskih središta. Trenutno stanje pojedinih podzemno željeznićkih sustava i njihova primjenjena tehnologija uvelike odražava stanje razvoja javnog gradskog prijevoza i mreže javnog gradskog prometa. Svaki od prijevoznika u podzemnim željeznicama u tim gradovima ima različiti tehnički pristup obavljanja javnog gradskog prijevoza te korištenjem optimalnim brojem motornih prijevoznih jedinica osigurava zadovoljenje potreba javnog gradskog i metropolitanskog područja grada. Kroz usporedbu tehničkih podataka pojedinih podzemnih željeznica može se uvidjeti i zaključiti koji od sustava podzemnih željeznica je veći i koje oblike tehničkih rješenja koristi. Ključne riječi: Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne, Liverpool, podzemna željeznica, javni gradski prijevoz, linija, tip vlaka, tvrtka, prihod, cijena. Summary Cities Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne and Liverpool are european cities with different metro system by wich development reflects economic situation of city areas. -

IINFORMATION for the DISABLED Disclaimer

Embassy of the United States of America Athens, Greece October 2013 IINFORMATION FOR THE DISABLED Disclaimer: The following information is presented so that you have an understanding of the facilities, laws and procedures currently in force. For official and authoritative information, please consult directly with the relevant authorities as described below. Your flight to Greece: Disabled passengers and passengers with limited mobility are encouraged to notify the air carrier/tour operator of the type of assistance needed at least 48 hours before the flight departure. Athens International Airport facilities for the disabled include parking spaces, wheelchair ramps, a special walkway for people with impaired vision, elevators with Braille floor-selection buttons, etc. For detailed information on services for disabled passengers and passengers with limited mobility, please visit the airport’s website, www.aia.gr Hellenic Railways Organization (O.S.E.): In Athens, the railway office for persons with disabilities is at Larissa main station. Open from 6 AM to midnight, it can be reached at tel.: 210-529-8838, in Thessaloniki at tel.: 2310-59-9071. Information on itineraries, fares and special services provided by the O.S.E. is available at: http://www.ose.gr. Recorded train schedule information can be obtained via Telephone number 1110. Ferries: The Greek Ministry of Merchant Marine reports most ferry companies offer accessibility and facilities for people with disabilities and has posted a list of companies on its website, www.yen.gr. For information concerning ferry schedules, please consult www.gtp.gr Athens Metro: Metro service connects Athens International Airport directly with city center. -

Athens Metro Athens Metro

ATHENSATHENS METROMETRO Past,Past, PresentPresent && FutureFuture Dr. G. Leoutsakos ATTIKO METRO S.A. 46th ECCE Meeting Athens, 19 October 2007 ATHENS METRO LINES HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS METRO NETWORK PHASES Line 1 (26 km, 23 stations, 1 depot, 220 train cars) Base Project (17.5 km, 20 stations, 1 depot, 168 train cars) [2000] First phase extensions (8.7 km, 4 stations, 1 depot, 126 train cars) [2004] + airport link 20.9 km, 4 stations (shared with Suburban Rail) [2004] + 4.3 km, 3 stations [2007] Extensions under construction (8.5 km, 10 stations, 2 depots, 102 train cars) [2008-2010] Extensions under tender (8.2 km, 7 stations) [2013] New line 4 (21 km, 20 stations, 1 depot, 180 train cars) [2020] LINE 1 – ISAP 9 26 km long 9 24 stations 9 3.1 km of underground line 9 In operation since 1869 9 450,000 passengers/day LENGTH BASE PROJECT STATIONS (km) Line 2 Sepolia – Dafni 9.2 12 BASE PROJECT Monastirakiι – Ethniki Line 3 8.4 8 Amyna TOTAL 17.6 20 HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS LENGTH PROJECTS IN OPERATION STATIONS (km.) PROJECTS IN Line 2 Ag. Antonios – Ag. Dimitrios 30.4 27 Line 3 Egaleo – Doukissis Plakentias OPERATION Doukissis Plakentias – Αirport Line 3 (Suburban Line in common 20.7 4 use with the Metro) TOTAL 51.1 31 HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS -

Athens, Greece Smarter Cities Challenge Report

Athens, Greece Smarter Cities Challenge report Contents 1. Executive summary 2 2. Introduction 5 A. The IBM Smarter Cities Challenge 5 B. The challenge 7 3. Findings, context, approach and roadmap 8 A. Findings, context and approach 8 B. Roadmap 10 4. Recommendations 12 1. Strengthen regulation enforcement in the city centre 12 Recommendation 1.1: Use technology to strengthen enforcement 15 Recommendation 1.2: Make it easier for people to adhere to regulations 19 2. Develop a comprehensive multimodal transportation strategy 21 Recommendation 2.1: Define and ensure compliance with rules on parking for tourist buses 22 Recommendation 2.2: Improve pedestrian streets and prioritise additional streets for conversion 24 Recommendation 2.3: Establish a long-term strategy to reduce the use of cars 30 3. Deploy intelligent transportation technology 32 Recommendation 3.1: Deploy an Operations Centre to aggregate data and to monitor and coordinate mobility for Attica 35 Recommendation 3.2: Redeploy and upgrade the Regional Traffic Management System 38 Recommendation 3.3: Deploy video analytics system 42 4. Cultivate public and private information sharing 44 Recommendation 4.1: Engage public and private businesses and citizens in cooperation through Open Data 46 Recommendation 4.2: Engage with inter-agency stakeholders to enable real-time information hub 47 5. Engage Athenians on the transportation vision through multimedia 48 Recommendation 5: Launch a campaign to engage the public to help reduce congestion and reclaim public spaces 52 6. Set the foundation for a Metropolitan Transportation Authority 53 Recommendation 6: Align governance with goals 58 5. Conclusion 59 6. Appendix 60 A. -

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Infrastructure, Transport and Networks

AHARNAE Kifissia M t . P ANO Lykovrysi KIFISSIA e LIOSIA Zefyrion n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT OPERATING LINES METAMORFOSI Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1, ISAP IRAKLIO Melissia LINE 2, ATTIKO METRO LIKOTRIPA LINE 3, ATTIKO METRO Kamatero MAROUSSI METRO STATION Iraklio FUTURE METRO STATION, ISAP Penteli IRAKLIO NERATZIOTISSA OTE EXTENSIONS Nea Filadelfia LINE 2, UNDER CONSTRUCTION KIFISSIAS NEA Maroussi LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli IONIA LINE 3, TENDERED OUT Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Ionia Aghioi OLYMPIAKO PENTELIS LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN & TENDERING AG.ANARGIRI Anargyri STADIO PERISSOS Nea "®P PARKING FACILITY - ATTIKO METRO Halkidona SIDERA DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa Suburban Railway Kallitechnoupoli ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei Halandri "®P o ®P Suburban Railway Section " Also Used By Attiko Metro e AGHIOS HALANDRI l "®P ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Railway Station a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI . PATISSIA GALATSI Aghia Peristeri THIMARAKIA P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini NIKOLAOS ANTONIOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P ATHENS KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera PANEPISTIMIO KERAMIKOS "®P MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS ZOGRAFOU THISSIO EVANGELISMOS Zografou Nikea ROUF SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios KESSARIANI PAGRATI Ioannis ACROPOLI Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani RENTIS SYGROU-FIX P KALITHEA TAVROS "® NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS LEFKA Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSHATO IOANNIS o Peania Dafni t KAMINIA Moshato Ymittos Kallithea t Drapetsona PIRAEUS DAFNI i FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Zitron Metro References

1 of 20 ZITRON METRO REFERENCES No. Project Client Contractor Fan Type Qty Country Year 1 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID FLATTER ZVM 1-12-18,5/6 28 SPAIN 1997 2 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVM 1-12-18,5/6 30 SPAIN 1997 3 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVP 1-12-18,5/6 -3,7/12 + ZVM 1-18-30/8 10 SPAIN 1997 4 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVP 1-12-18,5/6 -3,7/12 + ZVM 1-18-30/8 10 SPAIN 1997 5 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 6 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 7 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 8 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 9 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 10 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 11 LINEA 11 METRO MADRID ELECNOR ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-14-23/6-4,5/12 10 SPAIN 1998 12 LINEA 11 METRO MADRID ELECNOR ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-14-23/6-4,5/12 10 SPAIN 1998 13 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. -

Extreme Weather

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com MAY 2017 NO. 953 KEEPING RUNNING IN EXTREME WEATHER Los Angeles: Measure M funding boosts LRT expansion Terror targets the St Petersburg Metro US draft budget freezes out transit 14 hurt as Hong Kong tram overturns UK tram-train Chaos theory 05> £4.40 Under scrutiny yet Making sense of the looking to 2018 Charleroi Metro 9 771460 832050 Phil Long “A great event, really well organised and the dinner, reception and exhibition space made for great networking time.” Andy Byford – CEO, Toronto Transit Commission MANCHESTER “I really enjoyed the conference and made some helpful contacts. Thanks for bringing such a professional event together.” 18-19 July 2017 Will Marshall – Siemens Mobility USA Topics and themes for 2017 include: > Rewriting the business case for light rail investment > Cyber security – Responsibilities and safeguards > Models for procurement and resourcing strategies > Safety and security: Anti-vandalism measures > Putting light rail at the heart of the community > Digitisation and real-time monitoring > Street-running safety challenges > Managing obsolescence > Next-generation driver aids > Wire-free solutions > Are we delivering the best passenger environments? > Composite and materials technologies > From smartcard to smartphone ticketing > Rail and trackform innovation > Traction energy optimisation and efficiency > Major project updates Confirmed speakers include: > Paolo Carbone – Head of Public Transport Capital Programmes, Transport Infrastructure Ireland > Geoff Inskip – Chairman, UKTram > Jane Cole – Managing Director, Blackpool Transport > Allan Alaküla – Head of Tallinn EU Office, City of Tallinn > Andres Muñoz de Dios – Director General, MetroTenerife > Tobyn Hughes – Managing Director (Transport Operations), North East Combined Authority > Alejandro Moreno – Alliance Director, Midland Metro Alliance > Ana M. -

The World of Metro Rail in Pictures

THE WORLD OF METRO RAIL IN PICTURES "Dragon Boat Architecture" at Jiantan Metro Station, Taipei, Taiwan By Dr. F.A. Wingler, Germany, July 2020 Dr. Frank August Wingler Doenhoffstrasse 92 D 51373 Leverkusen [email protected] http://www.drwingler.com - b - 21st Century Global Metro Rail in Pictures This is Part II of a Gallery with Pictures of 21st Century Global Metro Rail, with exception of Indian Metro Rail (Part I), elaborated for a book project of the authors M.M. Agarwal, S. Chandra and K.K. Miglani on METRO RAIL IN INDIA . Metros across the World have been in operation since the late 1800s and transport millions of commuters across cities every day. There are now more than 190 Metro Installations globally with an average of about 190 million daily passengers. The first Metro Rail, that went underground, had been in London, England, and opened as an underground steam train for the public on 10st January 1863: llustration of a Train at Praed Street Junction near Paddington, 1863; from: History Today, Volume 63, Issue 1, January, 2013 Vintage London Underground Steam Train; Source “Made up in Britain” 1 Thed worl over, the 21st Century observed the opening of many new Metro Lines, the extension o f existing Metro Systems and the acquisition of modern Rolling Stocks, mostly in Asian Countries. In the last decades Urban Rail Transits in China developed fastest in the world. Urban Rail Transit in the People's Republic of China encompasses a broad range of urban and suburban electric passenger rail mass transit systems including subway, light rail, tram and maglev. -

A Questionnaire Study About Fire Safety in Underground Rail Transportation Systems

A questionnaire study about fire safety in underground rail transportation systems Karl Fridolf, Daniel Nilsson Department of Fire Safety Engineering and Systems Safety Lund University, Sweden Brandteknik och Riskhantering Lunds tekniska högskola Lunds universitet Lund 2012 A questionnaire study about fire safety in underground rail transportation systems Karl Fridolf, Daniel Nilsson Lund 2012 A questionnaire study about fire safety in underground rail transportation systems Karl Fridolf, Daniel Nilsson Report 3164 ISSN: 1402-3504 ISRN: LUTVDG/TVBB--3164--SE Number of pages: 25 Illustrations: Karl Fridolf Keywords questionnaire study, fire safety, evacuation, human behaviour in fire, underground rail transportation system, metro, tunnel. © Copyright: Department of Fire Safety Engineering and Systems Safety, Lund University Lund 2012. Brandteknik och Riskhantering Department of Fire Safety Engineering Lunds tekniska högskola and Systems Safety Lunds universitet Lund University Box 118 P.O. Box 118 221 00 Lund SE-221 00 Lund Sweden [email protected] http://www.brand.lth.se [email protected] http://www.brand.lth.se/english Telefon: 046 - 222 73 60 Telefax: 046 - 222 46 12 Telephone: +46 46 222 73 60 Fax: +46 46 222 46 12 Summary A questionnaire study was carried out with the main purpose to collect information related to the fire protection of underground rail transportation systems in different countries. Thirty representatives were invited to participate in the study. However, only seven responded and finally completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was available on the Internet and included a total of 16 questions, which were both close-ended and open-ended. Among other things, the questions were related to typical underground stations, safety instructions and exercises, and technical systems, installations and equipment. -

“Technical Consultant Services for Thessaloniki Metro Projects” Technical Data Document Rfp-256/14 Table of Contents 1. G

“TECHNICAL CONSULTANT SERVICES FOR THESSALONIKI METRO PROJECTS” RFP-256/14 TECHNICAL DATA DOCUMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GENERAL DATA – ADVISABILITY OF HIRING A TECHNICAL CONSULTANT 2. TECHNICAL SCOPE OF METRO PROJECTS 3. AM ACTIVITIES WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE METRO WORKS 4. THESSALONIKI METRO PROJECTS 5. CONSULTANT’S SCOPE OF SERVICES 6. DESCRIPTION OF POSITIONS AND QUALIFICATIONS OF THE CONSULTANT’S TECHNICAL PERSONNEL REQUIRED 7. SCHEDULE OF REQUIRED SERVICES Page 1 of 30 Technical Data FINAL “TECHNICAL CONSULTANT SERVICES FOR THESSALONIKI METRO PROJECTS” RFP-256/14 TECHNICAL DATA DOCUMENT 1. GENERAL DATA – ADVISABILITY OF HIRING A TECHNICAL CONSULTANT ATTIKO METRO A.E. (AM) was established by Law 1955/91 and its purpose is defined in Article 2 of the Second Article of Law 1955/91, as this was amended by Article 35 of Law 3203/03, and includes inter alia the design, construction, operation, running and development of the underground railway and Tramway network of Attica and Thessaloniki Prefectures.. The projects implemented by AM are projects requiring special technical skills involving multiple fields of expertise. AM is currently constructing the projects of the Athens Metro extension to Piraeus, the Tramway network extension to Piraeus, the Base Project of Thessaloniki Metro and its extensions to Kalamaria; moreover, at a design stage are the projects of Line 4, the extension to Ilion and to Glyfada, and projects executed on Line 1 in Athens, as well as the extensions of Thessaloniki Metro to Stavroupoli, Evosmos and the Airport. Taking the above into consideration and in order for AM to fulfill its obligations, it is necessary for it to seek the support of a specialized Technical Consultant for the projects of Thessaloniki Metro. -

Map of Athens Metro

M o u n t P e n t e l i k o Kifissia Zefyrion Lykovrysi KIFISSIA LEGEND KAT Metamorfosi OPERATING LINES LINE 1, ISAP Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 2, ATTIKO METRO Melissia LINE 3, ATTIKO METRO Kamatero MAROUSSI METRO STATION Iraklio Penteli EXTENSIONS IRAKLIO NERATZIOTISSA OTE LINE 2, UNDER CONSTRUCTION Nea Filadelfia LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION IRINI Maroussi NEA IONIA LINE 3, TENDERED OUT Petroupoli Ilion PEFKAKIA LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Nea Ionia Vrilissia LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN & TENDERING Agii Anargyri OLYMPIAKO STADIO PERISSOS Legend KIPOUPOLI Nea Halkidona SIDERA DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Suburban Railway Anthousa ANO PATISSIA Gerakas Suburban Railway Section Filothei Halandri Also Used By Attiko Metro AGHIOS ELEFTHERIOS HALANDRI ALSOS VEIKOU Railway Station ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi FILOTHEI AGHIA PARASKEVI PERISTERI KATO PATISSIA GALATSI Agia Paraskevi Peristeri Haidari Psyhiko NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS NIKOLAOS AGHIOS ANTONIOS Pallini PALLINI Neo Psihiko HOLARGOS Pikermi KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AMYNA ATTIKI AGIA MARINA Holargos DIKASTIRIA PANORMOU Agia Varvara EGALEO VICTORIA KATEHAKI ST.LARISSIS ATHENS AGHIA VARVARA ALEXANDRAS ELEONAS METAXOURGHIO EXARHIA AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo OMONIA Korydallos PEANIA-KANTZA GOUDI Glyka Nera PANEPISTIMIO KERAMEIKOS MEGARO MOUSSIKIS MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI KORYDALLOS ZOGRAFOU THISSIO EVANGELISMOS Zografou Nikea SYNTAGMA KESSARIANI ANO ILISSIA PAGRATI Agios Ioannis Redis PETRALONA ACROPOLI NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani SYGROU-FIX KALITHEA TAVROS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata NEOS KOSMOS Pireaus AGHIOS IOANNIS Vyronas MOSHATO s Peania o t Dafni t Moshato Ymittos i Kallithea m Drapetsona PIRAEUS DAFNI Y FALIRO t Nea Smyrni n u Ilioupoli o AGHIOS DIMITRIOS M DIMOTIKO THEATRO (AL. PANAGOULIS) AIRPORT Ilioupoli Agios Dimitrios Paleo Faliro ILIOUPOLI ALIMOS KOROPI Alimos Argyroupoli ARGYROUPOLI Koropi 0 500 1,000 2,000 May 2011 HELLINIKO m. -

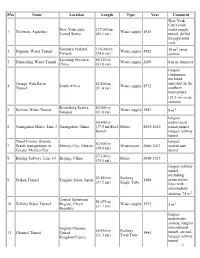

List of Longest Tunnels in the World

SNo Name Location Length Type Year Comment New York City's main New York state, 137,000 m water supply 1 Delaware Aqueduct Water supply 1945 United States (85.1 mi) tunnel, drilled through solid rock. Southern Finland, 120,000 m 2 2 Päijänne Water Tunnel Water supply 1982 16 m cross Finland (74.6 mi) section Liaoning Province, 85,320 m 3 Dahuofang Water Tunnel Water supply 2009 8 m in diameter China (53.0 mi) longest continuous enclosed Orange–Fish River 82,800 m aqueduct in the 4 South Africa Water supply 1972 Tunnel (51.4 mi) southern hemisphere (22.5 m2 cross section) Kronoberg/Scania, 82,000 m 5 Bolmen Water Tunnel Water supply 1987 2 Sweden (51.0 mi) 8 m longest 60,400 m metro/rapid 6 Guangzhou Metro: Line 3 Guangzhou, China (37.5 mi)Excl. Metro 2005-2010 transit tunnel branch longest railway tunnel Tunel Emisor Oriente: longest 62,500 m 7 Water management in Mexico City, Mexico Waterwaste 2006-2012 waterwaste (38.8 mi) Greater Mexico City tunnel 57,100 m 8 Beijing Subway: Line 10 Beijing, China Metro 2008-2012 (35.5 mi) longest railway tunnel excluding 53,850 m Railway 9 Seikan Tunnel Tsugaru Strait, Japan 1988 urban metro (33.5 mi) Single Tube lines with intermediate stations, 74 m2 Central Bohemian 51,075 m 10 Želivka Water Tunnel Region, Czech Water supply 1972 2 (31.7 mi) 5 m Republic longest underwater section, longest English Channel, international 50,450 m Railway 11 Channel Tunnel United 1994 tunnel, second- (31.3 mi) Twin Tube Kingdom/France longest railway tunnel 2 (2×45 m + 1×18 m2) Armenia (at the time of 48,300 m 12