INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 53Rd INTERNATIONAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Podzemne Željeznice U Prometnim Sustavima Gradova

Podzemne željeznice u prometnim sustavima gradova Lesi, Dalibor Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Fakultet prometnih znanosti Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:119:523020 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-04 Repository / Repozitorij: Faculty of Transport and Traffic Sciences - Institutional Repository SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FAKULTET PROMETNIH ZNANOSTI DALIBOR LESI PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA DIPLOMSKI RAD Zagreb, 2017. Sveučilište u Zagrebu Fakultet prometnih znanosti DIPLOMSKI RAD PODZEMNE ŽELJEZNICE U PROMETNIM SUSTAVIMA GRADOVA SUBWAYS IN THE TRANSPORT SYSTEMS OF CITIES Mentor: doc.dr.sc.Mladen Nikšić Student: Dalibor Lesi JMBAG: 0135221919 Zagreb, 2017. Sažetak Gradovi Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne i Liverpool su europski gradovi sa različitim sustavom podzemne željeznice čiji razvoj odgovara ekonomskoj situaciji gradskih središta. Trenutno stanje pojedinih podzemno željeznićkih sustava i njihova primjenjena tehnologija uvelike odražava stanje razvoja javnog gradskog prijevoza i mreže javnog gradskog prometa. Svaki od prijevoznika u podzemnim željeznicama u tim gradovima ima različiti tehnički pristup obavljanja javnog gradskog prijevoza te korištenjem optimalnim brojem motornih prijevoznih jedinica osigurava zadovoljenje potreba javnog gradskog i metropolitanskog područja grada. Kroz usporedbu tehničkih podataka pojedinih podzemnih željeznica može se uvidjeti i zaključiti koji od sustava podzemnih željeznica je veći i koje oblike tehničkih rješenja koristi. Ključne riječi: Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne, Liverpool, podzemna željeznica, javni gradski prijevoz, linija, tip vlaka, tvrtka, prihod, cijena. Summary Cities Hamburg, Rennes, Lausanne and Liverpool are european cities with different metro system by wich development reflects economic situation of city areas. -

Happy Birthday!

THE THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Quote of the Day “That’s what I love about dance. It makes you happy, fully happy.” Although quite popular since the ~ Debbie Reynolds 19th century, the day is not a public holiday in any country (no kidding). Happy Birthday! 1998 – Burger King published a full-page advertisement in USA Debbie Reynolds (1932–2016) was Today introducing the “Left-Handed a mega-talented American actress, Whopper.” All the condiments singer, and dancer. The acclaimed were rotated 180 degrees for the entertainer was first noticed at a benefit of left-handed customers. beauty pageant in 1948. Reynolds Thousands of customers requested was soon making movies and the burger. earned a nomination for a Golden Globe Award for Most Promising 2005 – A zoo in Tokyo announced Newcomer. She became a major force that it had discovered a remarkable in Hollywood musicals, including new species: a giant penguin called Singin’ In the Rain, Bundle of Joy, the Tonosama (Lord) penguin. With and The Unsinkable Molly Brown. much fanfare, the bird was revealed In 1969, The Debbie Reynolds Show to the public. As the cameras rolled, debuted on TV. The the other penguins lifted their beaks iconic star continued and gazed up at the purported Lord, to perform in film, but then walked away disinterested theater, and TV well when he took off his penguin mask into her 80s. Her and revealed himself to be the daughter was actress zoo director. Carrie Fisher. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) HURSDAY PRIL T , A 1, 2021 Today is April Fools’ Day, also known as April fish day in some parts of Europe. -

IINFORMATION for the DISABLED Disclaimer

Embassy of the United States of America Athens, Greece October 2013 IINFORMATION FOR THE DISABLED Disclaimer: The following information is presented so that you have an understanding of the facilities, laws and procedures currently in force. For official and authoritative information, please consult directly with the relevant authorities as described below. Your flight to Greece: Disabled passengers and passengers with limited mobility are encouraged to notify the air carrier/tour operator of the type of assistance needed at least 48 hours before the flight departure. Athens International Airport facilities for the disabled include parking spaces, wheelchair ramps, a special walkway for people with impaired vision, elevators with Braille floor-selection buttons, etc. For detailed information on services for disabled passengers and passengers with limited mobility, please visit the airport’s website, www.aia.gr Hellenic Railways Organization (O.S.E.): In Athens, the railway office for persons with disabilities is at Larissa main station. Open from 6 AM to midnight, it can be reached at tel.: 210-529-8838, in Thessaloniki at tel.: 2310-59-9071. Information on itineraries, fares and special services provided by the O.S.E. is available at: http://www.ose.gr. Recorded train schedule information can be obtained via Telephone number 1110. Ferries: The Greek Ministry of Merchant Marine reports most ferry companies offer accessibility and facilities for people with disabilities and has posted a list of companies on its website, www.yen.gr. For information concerning ferry schedules, please consult www.gtp.gr Athens Metro: Metro service connects Athens International Airport directly with city center. -

Athens Metro Athens Metro

ATHENSATHENS METROMETRO Past,Past, PresentPresent && FutureFuture Dr. G. Leoutsakos ATTIKO METRO S.A. 46th ECCE Meeting Athens, 19 October 2007 ATHENS METRO LINES HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS METRO NETWORK PHASES Line 1 (26 km, 23 stations, 1 depot, 220 train cars) Base Project (17.5 km, 20 stations, 1 depot, 168 train cars) [2000] First phase extensions (8.7 km, 4 stations, 1 depot, 126 train cars) [2004] + airport link 20.9 km, 4 stations (shared with Suburban Rail) [2004] + 4.3 km, 3 stations [2007] Extensions under construction (8.5 km, 10 stations, 2 depots, 102 train cars) [2008-2010] Extensions under tender (8.2 km, 7 stations) [2013] New line 4 (21 km, 20 stations, 1 depot, 180 train cars) [2020] LINE 1 – ISAP 9 26 km long 9 24 stations 9 3.1 km of underground line 9 In operation since 1869 9 450,000 passengers/day LENGTH BASE PROJECT STATIONS (km) Line 2 Sepolia – Dafni 9.2 12 BASE PROJECT Monastirakiι – Ethniki Line 3 8.4 8 Amyna TOTAL 17.6 20 HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS LENGTH PROJECTS IN OPERATION STATIONS (km.) PROJECTS IN Line 2 Ag. Antonios – Ag. Dimitrios 30.4 27 Line 3 Egaleo – Doukissis Plakentias OPERATION Doukissis Plakentias – Αirport Line 3 (Suburban Line in common 20.7 4 use with the Metro) TOTAL 51.1 31 HELLENIC MINISTRY FORFOR THETHE ENVIRONMENT,ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICALPHYSICAL PLANNINGPLANNING ANDAND PUBLICPUBLIC WORKSWORKS -

Athens, Greece Smarter Cities Challenge Report

Athens, Greece Smarter Cities Challenge report Contents 1. Executive summary 2 2. Introduction 5 A. The IBM Smarter Cities Challenge 5 B. The challenge 7 3. Findings, context, approach and roadmap 8 A. Findings, context and approach 8 B. Roadmap 10 4. Recommendations 12 1. Strengthen regulation enforcement in the city centre 12 Recommendation 1.1: Use technology to strengthen enforcement 15 Recommendation 1.2: Make it easier for people to adhere to regulations 19 2. Develop a comprehensive multimodal transportation strategy 21 Recommendation 2.1: Define and ensure compliance with rules on parking for tourist buses 22 Recommendation 2.2: Improve pedestrian streets and prioritise additional streets for conversion 24 Recommendation 2.3: Establish a long-term strategy to reduce the use of cars 30 3. Deploy intelligent transportation technology 32 Recommendation 3.1: Deploy an Operations Centre to aggregate data and to monitor and coordinate mobility for Attica 35 Recommendation 3.2: Redeploy and upgrade the Regional Traffic Management System 38 Recommendation 3.3: Deploy video analytics system 42 4. Cultivate public and private information sharing 44 Recommendation 4.1: Engage public and private businesses and citizens in cooperation through Open Data 46 Recommendation 4.2: Engage with inter-agency stakeholders to enable real-time information hub 47 5. Engage Athenians on the transportation vision through multimedia 48 Recommendation 5: Launch a campaign to engage the public to help reduce congestion and reclaim public spaces 52 6. Set the foundation for a Metropolitan Transportation Authority 53 Recommendation 6: Align governance with goals 58 5. Conclusion 59 6. Appendix 60 A. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Income Trom the Telephme Mtttee

- ~": ..--- .. ISBA ~tAt£ UIG~ loe UOO • aT 18 pages ' :i'Fi :::::' ..... ::""';;, three sections HERA Ocr ar ... NINETY ·TlllRD YEAR Second Cislis Postage Paid at Wayne, -NIOOIER'II'TY'IIEVDI Absentee, Blind, Disabled Voters Should Take Steps to Vote Tuesday ack of Quorum Slows Work Voterll who are gotng to be abient from Wayne County m their ballots m Tue8da.Y, Weible Tuollday have ml,y mtll Set ...• stated. dllJ( to appl,y In writing for an Following Is a ",omplete list absentee ball(t,accordfngtoNor ing ct where Wayne COtnty vot~ s Council Meets Tuesday ria Weible, eounty clerk. Ap ers are to cast their bellots: -+---------- ~ck rt • quorum ItOIlI>Od tho pUcatim can be made at the Wayne, First Ward (south d city c....,11 from dolnr..,..h d .lGI to ltart work within 30 cotllty clerk's dftce In the Wayne Filth Street and those In Wrledt's .. bualne .. Tueo4ay nllht, 1U day. and complete the job ..tthkl C 0tIIty courthouse. secood addltloo south or east d ,atch Out For C.....,II ..... Ed Smith rot out d 210 day,. H the vlXer does not make out Valley drlve}-Fire Hall; Secood hll sick bed lq encqb to per 8«i.h low bidden were .,ked the written appUcattoo he wtIl Ward (north cI. Fifth and east d UHle Goblins mit the ('OI.I\cll toapproveclalmJ. to .ubmit deltan lpecUlcatlon1 Mafn}-Publlc Library; Third not be able to cast an ahllentee lC1llgti Is that special nlghl: wid "III a retoll'lm r1 nece ... for eommlttee It~ Wednelday taUot In Tuesday' 8 general elec Ward (north ci Fifth and west d ci'l the year when little goblbts, Itty Cor the creatloo d Storm momlna· ttm, Weible warned. -

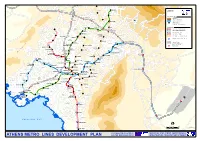

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Infrastructure, Transport and Networks

AHARNAE Kifissia M t . P ANO Lykovrysi KIFISSIA e LIOSIA Zefyrion n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT OPERATING LINES METAMORFOSI Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1, ISAP IRAKLIO Melissia LINE 2, ATTIKO METRO LIKOTRIPA LINE 3, ATTIKO METRO Kamatero MAROUSSI METRO STATION Iraklio FUTURE METRO STATION, ISAP Penteli IRAKLIO NERATZIOTISSA OTE EXTENSIONS Nea Filadelfia LINE 2, UNDER CONSTRUCTION KIFISSIAS NEA Maroussi LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli IONIA LINE 3, TENDERED OUT Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Ionia Aghioi OLYMPIAKO PENTELIS LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN & TENDERING AG.ANARGIRI Anargyri STADIO PERISSOS Nea "®P PARKING FACILITY - ATTIKO METRO Halkidona SIDERA DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa Suburban Railway Kallitechnoupoli ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei Halandri "®P o ®P Suburban Railway Section " Also Used By Attiko Metro e AGHIOS HALANDRI l "®P ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Railway Station a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI . PATISSIA GALATSI Aghia Peristeri THIMARAKIA P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini NIKOLAOS ANTONIOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P ATHENS KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera PANEPISTIMIO KERAMIKOS "®P MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS ZOGRAFOU THISSIO EVANGELISMOS Zografou Nikea ROUF SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios KESSARIANI PAGRATI Ioannis ACROPOLI Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani RENTIS SYGROU-FIX P KALITHEA TAVROS "® NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS LEFKA Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSHATO IOANNIS o Peania Dafni t KAMINIA Moshato Ymittos Kallithea t Drapetsona PIRAEUS DAFNI i FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Los Deportes Alternativos En La Escuela

10mo Congreso Argentino de Educación Física y Ciencias. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Departamento de Educación Física, La Plata, 2013. Los deportes alternativos en la escuela. Aromando, Marcelo Damián. Cita: Aromando, Marcelo Damián (2013). Los deportes alternativos en la escuela. 10mo Congreso Argentino de Educación Física y Ciencias. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Departamento de Educación Física, La Plata. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-049/166 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. 10º Congreso Argentino y 5º Latinoamericano de Educación Física y Ciencias 1 a. Título: LOS DEPORTES ALTERNATIVOS EN LA ESCUELA: b. Autor: MARCELO DAMIAN AROMANDO [email protected] c. Resumen: En la búsqueda de nuevas propuestas, experimentando, haciendo cursos y compartiendo experiencias; no sólo con otros y otras profes sino también con gente a la que le gusta el deporte y el movimiento como estilo de vida, descubrí un abanico inmenso de posibilidades y encontré que los deportes alternativos pueden ser un recurso integrador de edades, sexos y estados físicos adecuándose con facilidad a cualquier espacio y así poder sumar a “lo convencional y tradicional” de la Educación Física, y que todas las personas (niño/a- adolescente-adulto/a) puedan realizar deportes con facilidad y placer. -

Zitron Metro References

1 of 20 ZITRON METRO REFERENCES No. Project Client Contractor Fan Type Qty Country Year 1 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID FLATTER ZVM 1-12-18,5/6 28 SPAIN 1997 2 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVM 1-12-18,5/6 30 SPAIN 1997 3 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVP 1-12-18,5/6 -3,7/12 + ZVM 1-18-30/8 10 SPAIN 1997 4 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. ZVP 1-12-18,5/6 -3,7/12 + ZVM 1-18-30/8 10 SPAIN 1997 5 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 6 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 7 ESTACION ALAMEDA II METRO LISBOA MAQUINTER-SOTECNICA ZVM 1-20-75/6-7,5/12 + ZVM 1-10-18/6-3,7/12 + ZVM 1-10-8,5/6-1,8/12 8 PORTUGAL 1998 8 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 9 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 10 LINEA 5 METRO MADRID ATIL - COBRA ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-12-18,5/6-3,7/12 + JZ 7-15/2 8 SPAIN 1998 11 LINEA 11 METRO MADRID ELECNOR ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-14-23/6-4,5/12 10 SPAIN 1998 12 LINEA 11 METRO MADRID ELECNOR ZVM 1-18-30/8 + ZVP 1-14-23/6-4,5/12 10 SPAIN 1998 13 LINEA 4 METRO MADRID ISOLUX WAT, S.A. -

Year Host Country Men's Singles Men's

YEAR HOST COUNTRY MEN’S SINGLES MEN’S PAIRS MEN’S TRIPLES MEN’S FOURS MEN’S TROPHY Keith Poole (s) George Souza (s) Maurice Symes (s) Don Sherman Peter Fong M B (Junior)Hassan 1985 Tweed Heads, AUSTRALIA Wayne Nairn Arthur Black AUSTRALIA - FIJI David Tso - NEW ZEALAND Wally Bonagura - HONG KONG - AUSTRALIA Tau Nancie (s) Darby Ross (s) Dennis Katunarich (s) Laka Rawali Ken Williams Ken Williams 1987 Lae, PAPUA NEW GUINEA William Wain Eddie Loa AUSTRALIA - AUSTRALIA Trevor Morris - AUSTRALIA Peter Pomaleu - AUSTRALIA - PAPUA NEW GUINEA Rex Johnston (s) Rex Johnston (s) Rob Parella (s) Terry McCabe Rob Parella Terry McCabe 1989 Suva, FIJI Dennis Katunarich Dennis Katunarich AUSTRALIA - AUSTRALIA Ken Williams - AUSTRALIA Ken Williams - AUSTRALIA - AUSTRALIA Bill Boettger (s) George Souza (s) Bill Boettger (s) Dave Houtby Rob Parella David Tso 1991 Hong Kong, CHINA Ronnie Jones Dave Brown CANADA - AUSTRALIA Mel Stewart - CANADA Ronnie Jones -HONG KONG - CANADA Steven Anderson (s) Steven Anderson (s) Bill Boettger (s) Steve Srhoy Cameron Curtis David Stockham 1993 Victoria, CANADA Mark Gilliland David Stockham AUSTRALIA - AUSTRALIA Sam Laguzza - CANADA Sam Laguzza - AUSTRALIA - AUSTRALIA Peter Belliss (s) Peter Belliss (s) Gary Lawson (s) Gary Lawson Kelvin Kerkow David File 1995 Dunedin, NEW ZEALAND Rowan Brassey David File NEW ZEALAND - AUSTRALIA Andrew Curtain - NEW ZEALAND Andrew Curtain - NEW ZEALAND - NEW ZEALAND Peter Belliss (s) Peter Belliss (s) Peter Shaw (s) Peter Shaw Rowan Brassey Russell Meyer 1997 Warilla, AUSTRALIA Rowan Brassey -

SPECIAL BURNSIDE EVENTS 29 Neighbouring Clubs Competed with Each Other for Format Be Changed from 42 Players

SPECIAL BURNSIDE EVENTS draws and delivered Burnside Invitation Pairs results in minutes. It has been further refined This tournament has become one of ‘the’ events on the and is now used in NZ bowling calendar. Players are nominated by the New tournaments around the Zealand and Australian selectors as well as by provincial world including World centres from around the country. The Pairs event Bowls events. gives young players experience playing elite bowlers while allowing selectors to gauge the form of their top Since 2006, Geoff Clarke Geoff Clarke, Convenor players. As the event occurs soon after the National has been a very effective Burnside Pairs 2006-present Championships each year, convenors have always been and innovative convenor. Each convenor and their able to attract several current national champions to take respective organising committees have learnt from and part. In-form Burnside players have been rewarded by built on the success of previous years to ensure the selection and have performed creditably over the years. event’s stature is enhanced. Held over 3 days the 2x2x2x2 bowl format is very popular In 2007 the tournament was renamed the Stewart Buttar with players. Traditionally the tournament starts on the Burnside Invitation Pairs in honour of Stewart Buttar. The Thursday evening with a “pro-am” tournament designed winners’ trophy, Stewart’s shirt from World Bowls 2004 to thank the large number of volunteers from the Club, signed by the NZ team he coached, was framed and welcome the players and officially open the event. remains in place above the bar in the lounge.