Who's Afraid of the Rubber Man? Perversions and Subversions Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Superintendent's Update / Page 2 of 16

The Superintendent’s Update June 3, 2015 NEWS FROM KELLY While this past year definitely presented challenges, there were also many successes. CUSD continues to provide excellent educational opportunities for our students, and this is never more evident than at this time of the year. Our students are winning awards, graduating, and heading off to all parts of the country to further their education and continue their lives. They are able to do this because of the education and support they received here in Chico. Thank you to each and every CUSD staff member as each of you plays a role in the success of our students—and they are why we are all here. While it is exciting to see our students promote from one grade to the next, and ultimately graduate, it is much harder when it comes to saying goodbye to our colleagues when they make that decision to “graduate” into retirement. We see their happiness, and we want to be happy for them, but still, it is hard to envision not having them with us when we come back and start the new school year. To help those of us they are leaving behind, we ask our retirees to find some time occasionally to come by and say hello as they will be missed. Please join me in congratulating the following CUSD staff members who have either retired during the 2014-2015 school year or who have submitted their intent to retire at the end of this school year. They have my sincere appreciation for their years of dedication to education and I wish them all health and happiness in their retirement. -

Queer Identities Rupturing Dentity Categories and Negotiating Meanings of Oueer

Queer Identities Rupturing dentity Categories and Negotiating Meanings of Oueer WENDY PETERS Ce projet dPcrit sept Canadiennes qui In the article, "The Politics of constructed by available discourses shpproprient le terme "queerJ'comme InsideIOut," Ki Namaste recom- (Foucault). Below, I describe some orientation sexuelk et en explore ks mends that queer theoreticians pay of the meanings participants as- dzfirentes signt$cations. Leur identiti attention to the diversity of non- cribed to queer, and explore the et expiriencespointent rt. certaines ca- heterosexual identities. I created the ways in which queer was under- tigories sexuelles existantes comme les- following research project through stood and represented by people biennes et hitirosexuelles. my interest in queer theory and a who claim, or have claimed, queer subsequent recognition that queer, as their sexuality identity category. In the 1990s, the term "queer" gained as described in queer theory, is an The first person to email the new acceptance within poststruct- excellent description for my sexu- listserv identified herself as uralistlpostmodernist thought. In ality and gender practices. Since "Stressed!" Stressed wrote often part, this was an attempt to move queer is a term that resists a static about trying to finish her gradu- away from reproducing the hetero- definition, I was curious to see who ate-level thesis, and chose her alias sexist binary of heterosexual and ho- else was claiming queer as an iden- to reflect her current state of mind. mosexual. Queer theory contends that tity category and what it meant for She related how her claiming of in order to challenge heteronorma- them. After sending an email to queer as an identity category came tivity, we need to go beyond replac- friends and various listservs detail- through her coming-out process ing one restrictive category with an- ing my interest in starting an aca- and her reluctance to choose a sexu- other. -

Following Is a List of All 2019 Festival Jurors and Their Respective Categories

Following is a list of all 2019 Festival jurors and their respective categories: Feature Film Competition Categories The jurors for the 2019 U.S. Narrative Feature Competition section are: Jonathan Ames – Jonathan Ames is the author of nine books and the creator of two television shows, Bored to Death and Blunt Talk His novella, You Were Never Really Here, was recently adapted as a film, directed by Lynne Ramsay and starring Joaquin Phoenix. Cory Hardrict– Cory Hardrict has an impressive film career spanning over 10 years. He currently stars on the series The Oath for Crackle and will next be seen in the film The Outpostwith Scott Eastwood. He will star and produce the film. Dana Harris – Dana Harris is the editor-in-chief of IndieWire. Jenny Lumet – Jenny Lumet is the author of Rachel Getting Married for which she received the 2008 New York Film Critics Circle Award, 2008 Toronto Film Critics Association Award, and 2008 Washington D.C. Film Critics Association Award and NAACP Image Award. The jurors for the 2019 International Narrative Feature Competition section are: Angela Bassett – Actress (What’s Love Got to Do With It, Black Panther), director (Whitney,American Horror Story), executive producer (9-1-1 and Otherhood). Famke Janssen – Famke Janssen is an award-winning Dutch actress, director, screenwriter, and former fashion model, internationally known for her successful career in both feature films and on television. Baltasar Kormákur – Baltasar Kormákur is an Icelandic director and producer. His 2012 filmThe Deep was selected as the Icelandic entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 85th Academy Awards. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

America's Closet Door: an Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 12-2014 America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality Sara Moroni University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moroni, Sara, "America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality" (2014). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America’s Closet Door An Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality Sara Moroni Departmental Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga English Project Director: Rebecca Jones, PhD. 31 October 2014 Christopher Stuart, PhD. Heather Palmer, PhD. Joanie Sompayrac, J.D., M. Acc. Signatures: ______________________________________________ Project Director ______________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Liaison, Departmental Honors Committee ____________________________________________ Chair, Departmental Honors Committee 2 Preface The 2013 “American Time Use Survey” conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculated that, “watching TV was the leisure activity that occupied the most time…, accounting for more than half of leisure time” for Americans 15 years old and over. Of the 647 actors that are series regulars on the five television broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, The CW, Fox, and NBC) 2.9% were LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender) in the 2011-2012 season (GLAAD). -

UNIVERSIDAD POLITECNICA DE VALENCIA ESCUELA POLITECNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado En Comunicación Audiovisual

UNIVERSIDAD POLITECNICA DE VALENCIA ESCUELA POLITECNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual “American Horror Story, análisis de la dirección de fotografía en una serie de televisión” TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: Isaac Almendros Tolosa Tutor/a: Rebeca Díez Somavilla GANDIA, 2014 PORTADA 2 Agradecimientos A Sergio Gómez por su trabajo maquetan- do. A mis amigos por compartir en la distancia las horas, amarguras y experiencias de hacer un TFG en verano, así como a los que han co- laborado y animado. Y por último, a mi tutora Rebeca Díez, por toda su dedicación corrigien- do, ayudando y motivando. 3 RESUMEN Este trabajo final de grado consiste en un análisis de la dirección de fotografía de las dos pri- meras temporadas de la serie de televisión American Horror Story. En el trabajo se verá cómo la fotografía influye en la serie, teniendo en cuenta la importancia de la fotografía como uno de los lenguajes que complementan al resto de los lenguajes audiovisuales. También se pretende com- prender de qué herramientas, técnicas, y elementos fotográficos hacen uso, y para qué, es decir de qué modo son empleadas para conseguir transmitir unas sensaciones y emociones que apoyen la narrativa de la historia. Palabras clave: dirección de fotografía, serie, televisión, American Horror Story, análisis. ABSTRACT This final degree project is an analysis of the cinematography of the two first seasons of the TV show American Horror Story. In this essay we will see how cinematography influences into the series, taking into account the importance of photography as one of the languages that comple- ment the rest of audiovisual languages. -

You Mentioned That Some Scenes from James Ellroy's LA CONFIDENTIAL

89 FAQ 6 6.1 Q: You mentioned that some scenes from James Ellroy’s L.A. CONFIDENTIAL were filmed inside the Hodel/Franklin House. I didn’t see any. Which ones? Yes, two separate scenes were filmed inside the Franklin House, but if you blink you miss them. George Hodel 1949 David Strathairn as “Pierce Patchett” 90 L.A. CONFIDENTIAL FRANKLIN HOUSE SCENE 1 Scene between Kevin Spacey and James Cromwell (Capt. Dudley Smith) This 1996-7 scene filmed in Hodel-Franklin House kitchen five years before residential interior renovation in 2002 L.A. CONFIDENTIAL FRANKLIN HOUSE SCENE 2 Scene at Franklin House with partygoers (Hookers and tricks) This scene filmed in Hodel-Franklin House living-room in 1996-7 91 Kevin Spacey as detective Sgt. Jack Vincennes holding Pierce Patchett’s Fleur dy Lis business card George Hodel’s “Whatever You Desire” Fleur dy Lis photo album As in CHINATOWN, there are some fascinating coincidences related to the real life George Hodel and the characters in the fictional Ellroy novel, masterfully adapted to film in 1997 by director, Curtis Hanson. First is the character, Pierce Patchett, who not only resembles George Hodel in physical appearance and voice, but is presented in the film as a powerful L.A. behind-the-scenes shadow figure, running a vice operation and working with corrupt cops. Pimp Patchett has high class prostitutes going to cocktail parties and entertaining wealthy and connected businessmen AT THE FRANKLIN HOUSE. (See above clips) Incredibly, this is something that Dr. George Hodel did in real life, at the same location, in the very same room! Patchett’s logo is the Fluer dy Lis, which we see on George Hodel’s private, personal album of loved ones. -

Table of Contents Abstract

Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………. …….. 2. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….. 3-5. Theoretical approaches………………………………………………………………………. 5-12. On reading Ryan Murphy’s critical creation(s)……………………………………………… 12-14. An analysis of the symbolical power present within the composition of the American nuclear family and how it is critiqued through its representation in American Horror Story: Murder House………………………………………………………………………………………… 14-62. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………… 62-64. Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………….. 65-66. 1 Abstract This Master’s Thesis is a psychoanalytical investigation into the critical interpretation of the traditional family practice taking place within contemporary American society as it is vividly mediated out to the viewing masses of the world by Ryan Murphy in his 2011 FOX series American Horror Story: Murder House. By making an individual analysis of each relevant episode with the theoretical propositions made by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud such as that of ‘the unconscious’, ‘the perceptive aspects of the primary and secondary processes’, ‘the repetition compulsion’, as well as the ‘final model of the mind’ and the theoretical composition of ‘the abject’ by philosopher Julia Kristeva readily at hand, this Master’s Thesis functions to bring a critique of how the American nuclear family remains an unchangeable product of its past sociological definition that places the validating notion of embodying the American (nuclear family) dream on a pedestal never to be obtainable to the desire driven psychological being of the American individual, who is indeed forever expected to pursue it, even in death. The main oppositional focus of the thesis is centered on sociologist George Peter Murdoch’s 1949 definition of ‘the nuclear family’ and its compatibility with the society in which it is expected to manifest itself by viewing it in the contextual framework of yet another cornerstone that can be found at the baseline of American society, one that is commonly known as the American dream. -

4-5-16 Transcript Bulletin

FRONT PAGE A1 TOOELE Stansbury beats TRANSCRIPT Lehi in pitchers’ duel SERVING See B1 TOOELE COUNTY BULLETIN SINCE 1894 TUESDAY April 5, 2016 www.TooeleOnline.com Vol. 122 No. 89 $1.00 Overused Mormon Trail Road falling apart by Tim Gillie STAFF WRITER With potholes and cracks, Mormon Trail Road in some places has more patches than road, according to Tooele County Commission Chairman Wade Bitner. Beat up by the impact of heavy gravel trucks the road wasn’t designed to carry, Tooele County commissioners are contem- plating the future of what once was a dirt path that connected Grantsville with early settlers in Rush Valley. The nearly 19-mile road runs from the west side of Grantsville to Rush Valley. Last week, Tooele County filled potholes and worn-out portions of Mormon Trail Road south of South Mountain Road with gravel. This week, a contractor begins regular pothole repairs of Mormon Trail Road north of South Mountain Road, Bitner said. At $2.70 per square-foot of pothole filling, the county has budgeted $50,000 for pothole repair countywide for 2016. The contractor will begin with Mormon Trail Road, but the $50,000 includes work on Erda Way, Burmester Road, and other county roads, according to Rod Thompson, Tooele County Roads Department director. The last major overhaul of Mormon Trail Road was around 25 years ago, he said. FRANCIE AUFDEMORTE/TTB PHOTOS At that time the road’s main A gravel truck (top) travels through a damaged section of Mormon traffic was light vehicles — pas- Trail Road. The road has been beaten up by the impact of heavy gravel senger cars and pickup trucks trucks it wasn’t designed to carry, and the Tooele County commis- — using the road as a shortcut to sioners are currently contemplating the road’s future, according to Rush Valley. -

ITEMS ADDED APRIL 2021.Xlsx

ITEMS ADDED APRIL 2021 Call Number Title Author DVD B-1022 Barb & Star go to Vista Del Mar DVD E-1023 Earwig and the witch DVD H-1024 Hello, Dolly! DVD K-1025 The king and I DVD O-1026 Oklahoma! DVD S-1027 South Pacific AUD-CD A Modern romance : an investigation Ansari, Aziz 1983- AUD-CD B Capitol murder Bernhardt, William 1960- AUD-CD C The Mayan secrets Cussler, Clive. AUD-CD C The assassin Coonts, Stephen 1946- AUD-CD D Summit Lake Donlea, Charlie AUD-CD E The black dahlia Ellroy, James 1948- AUD-CD G "V" is for vengeance Grafton, Sue AUD-CD G T is for trespass Grafton, Sue. AUD-CD G The ideal man a novel Garwood, Julie. AUD-CD H To die for Howard, Linda 1950- AUD-CD L The blind side : [the evolution of a game] Lewis, Michael (Michael M.) AUD-CD W Collateral damage Woods, Stuart. J-AV T We are not from here Torres Sanchez, Jenny 248 WILTON Saturdays with Billy : my friendship with Billy Graham Wilton, Don 306.874 BACKMAN Things my son needs to know about the world Backman, Fredrik 1981- 576.5 ISAACSON The code breaker : Jennifer Doudna, gene editing, and theIsaacson, future of Walterthe human race 598.7 DUNN The glitter in the green : in search of hummingbirds Dunn, Jon (Conservationist) 613 BROADY The calcium connection : the little-known enzyme at the rootBroady, of your Brunde cellular health 616.895 STEVEN Breaking bipolar : break the hold bipolar disorder has overSteven, your life Troy 658.3 FROST Work-from-home hacks : 500+ easy ways to get organized,Frost, stay Aja productive, and maintain a work-life balance while working from home! 741.597 MARVEL Marvel encyclopedia : new edition 757.6 BUSH Out of many, one : portraits of America's immigrants Bush, George W. -

CU Report Shows Increased Construction Activity by RICK NORTON Number of Meter Sets Completed by CU Includes 10 Months (July 2015 Through When 423 Were Recorded

MONDAY 162nd YEAR • NO. 44 jUNE 20, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ CU report shows increased construction activity By RICK NORTON number of meter sets completed by CU includes 10 months (July 2015 through when 423 were recorded. The largest 21 single-family homes, 17 townhomes, Associate Editor line crews. April 2016), CU crews had installed 320 amount of meter sets, based on the three apartments and three commercial A meter set is the physical connection meter sets, as compared to 265 during chart’s range, came in 1998-99 with 565 projects. Bradley County’s recent drop in between a new, or remodeled, develop- the same corresponding period a year connections. The lowest point, within the In a related report regarding water — unemployment to a 15-year low of 3.6 ment (residential or commercial) and earlier. The year-to-date amount for chart’s span, came in 2009-10 with 210. except this one involves rainwater percent has been credited in part to CU’s existing water system. An increase April 2014 was 257. Mullinax pointed out the average instead of water meters — Mullinax increased hiring in construction, and a in water meter sets generally points to a Mullinax said the 320 meter sets, as of number of water meter sets completed reported rainfall amounts for the year recent update heard by the Cleveland hike in construction activity. April 2016, represented a 21 percent by CU crews during the month of April is are falling far short of the Cleveland Board of Public Utilities appears to verify For the month of April, CU line crews increase over the previous year. -

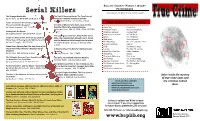

Serial Killers

Bullitt County Public Library Serial Killers Pathfinders Books, Movies, and More on Your Favorite Subjects The Stranger Beside Me The Devil’s Rooming House: The True Story of by Ann Rule CD BOOK 364.152 RULE, E-audio America’s Deadliest Female Serial Killer by William M. Phelps 364.15 PHEL, E-book Zodiac Unmasked: The Identity of America's Most Films Based on True Crime Elusive Serial Killer Revealed The Girls of Murder City: Fame, Lust, and the by Robert Graysmith 364.152 GRAY Beautiful Killers Who Inspired Chicago Alpha Dog Goodfellas by Douglas Perry 364.152 PERR, LT 364.152 PERR, American Hustle Heavenly Creatures Naming Jack the Ripper E-audio American Gangster Hoodwinked by Russell Edwards 364.152 EDWA, E-book Anatomy of a Murder In Cold Blood The Good Nurse: America’s Most Prolific Serial Bernie The Infiltrator Inside the Mind of BTK: The True Story Behind Killer, the Hospitals that Allowed Him to Thrive, Black Mass The Informant! Thirty Years of Hunting for the Wichita Serial Killer and the Detectives Who Brought Him to Justice by John E. Douglas 364.15 DOUG by Charles Graeber B CULL, LT 364.152 GRAE, The Bling Ring The Jeffrey Dahmer Files E-audio Bonnie and Clyde Legend Green River, Running Red: The Real Story of the Bully The Newton Boys Green River Killer, America's Deadliest Serial A Rose for Mary: The Hunt for the Real Boston Captive The Next Three Days Murderer Strangler Catch Me If You Can Public Enemies by Ann Rule 364.152 RULE, E-book by Casey Sherman 364.15 SHER Changeling Serpico Cleveland Abduction True Story The