Table of Contents Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Montevallo TRIO Mcnair Scholars Program 2018 Research

University of Montevallo TRIO McNair Scholars Program 2018 Research Journal Welcome! Undergraduate research is the pinnacle in undergraduate education as it truly is a comprehensive learning experience. One of the reasons I am so passionate about undergraduate research is that I have seen in some of my students over the years a transformation which is undeniable when they do an undergraduate research project. It requires the student to draw knowledge obtained from many different courses and venture into the unknown, where standardized laboratory experiments are a thing of the past. When research students discover something that has never before been known, it is most exhilarating. Seeing students transformed as a result of the undergraduate research experience is very rewarding. It is this I cherish as a teacher and researcher. The University of Montevallo Undergraduate Research Program coupled with the Ronald E. McNair Scholars Program provide undergraduates from all fields of study the opportunity to conduct research under the guidance of an experienced faculty member. The relationship that is created and nurtured as these projects are carried out is remarkable. The guidance students receive in a research setting is undeniably one of the greatest benefits. In addition to learning research methods and improving critical thinking skills, completing an undergraduate research project affords the student an opportunity to present their research to their community of scholars at professional meetings and conferences. Learning to communicate the results they have obtained with the world around them is a feat in and of itself. This certainly assists students as they prepare for graduate school and their future career. -

UNIVERSIDAD POLITECNICA DE VALENCIA ESCUELA POLITECNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado En Comunicación Audiovisual

UNIVERSIDAD POLITECNICA DE VALENCIA ESCUELA POLITECNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Grado en Comunicación Audiovisual “American Horror Story, análisis de la dirección de fotografía en una serie de televisión” TRABAJO FINAL DE GRADO Autor/a: Isaac Almendros Tolosa Tutor/a: Rebeca Díez Somavilla GANDIA, 2014 PORTADA 2 Agradecimientos A Sergio Gómez por su trabajo maquetan- do. A mis amigos por compartir en la distancia las horas, amarguras y experiencias de hacer un TFG en verano, así como a los que han co- laborado y animado. Y por último, a mi tutora Rebeca Díez, por toda su dedicación corrigien- do, ayudando y motivando. 3 RESUMEN Este trabajo final de grado consiste en un análisis de la dirección de fotografía de las dos pri- meras temporadas de la serie de televisión American Horror Story. En el trabajo se verá cómo la fotografía influye en la serie, teniendo en cuenta la importancia de la fotografía como uno de los lenguajes que complementan al resto de los lenguajes audiovisuales. También se pretende com- prender de qué herramientas, técnicas, y elementos fotográficos hacen uso, y para qué, es decir de qué modo son empleadas para conseguir transmitir unas sensaciones y emociones que apoyen la narrativa de la historia. Palabras clave: dirección de fotografía, serie, televisión, American Horror Story, análisis. ABSTRACT This final degree project is an analysis of the cinematography of the two first seasons of the TV show American Horror Story. In this essay we will see how cinematography influences into the series, taking into account the importance of photography as one of the languages that comple- ment the rest of audiovisual languages. -

American Horror Story" As Adaptation of E

"American Horror Story" as Adaptation of E. A. Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher" Mikolčić, Monika Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:177051 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i hrvatskoga jezika i književnosti Monika Mikolčić "Američka horor priča" kao adaptacija "Pada kuće Usherovih" E. A. Poea Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i hrvatskoga jezika i književnosti Monika Mikolčić "Američka horor priča" kao adaptacija "Pada kuće Usherovih" E. A. Poea Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Croatian Language and Literature Monika Mikolčić American Horror Story as Adaptation of E. A. Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher" Bachelor's Thesis Supervisor: Ljubica Matek, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Osijek, 2019 J.J. -

Nomination Press Release

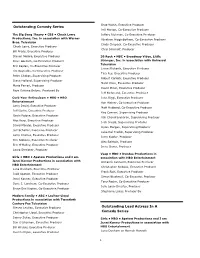

Outstanding Comedy Series 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Television The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Productions, Inc. in association with Warner Tina Fey as Liz Lemon Bros. Television Veep • HBO • Dundee Productions in Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO association with HBO Entertainment Entertainment Julia Louis-Dreyfus as Selina Meyer Girls • HBO • Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner Productions in association with HBO Entertainment Outstanding Lead Actor In A Modern Family • ABC • Levitan-Lloyd Comedy Series Productions in association with Twentieth The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Century Fox Television Productions, Inc. in association with Warner 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Bros. Television Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Jim Parsons as Sheldon Cooper Television Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO Veep • HBO • Dundee Productions in Entertainment association with HBO Entertainment Larry David as Himself House Of Lies • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Crescendo Productions, Totally Outstanding Lead Actress In A Commercial Films, Refugee Productions, Comedy Series Matthew Carnahan Circus Products Don Cheadle as Marty Kaan Girls • HBO • Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner Productions in association with Louie • FX Networks • Pig Newton, Inc. in HBO Entertainment association with FX Productions Lena Dunham as Hannah Horvath Louis C.K. as Louie Mike & Molly • CBS • Bonanza Productions, 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Inc. in association with Chuck Lorre Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Productions, Inc. and Warner Bros. Television Television Alec Baldwin as Jack Donaghy Melissa McCarthy as Molly Flynn Two And A Half Men • CBS • Chuck Lorre New Girl • FOX • Chernin Entertainment in Productions Inc., The Tannenbaum Company association with Twentieth Century Fox in association with Warner Bros. -

American Horror Story

February 14, 2011 Writer’s Draft American Horror Story written by Ryan Murphy & Brad Falchuk directed by Ryan Murphy RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2011 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. NO PORTION OF THIS SCRIPT MAY BE PERFORMED, PUBLISHED, REPRODUCED, SOLD, OR DISTRIBUTED BY ANY MEANS OR QUOTED OR PUBLISHED IN ANY MEDIUM, INCLUDING ANY WEB SITE, WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT OF TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION. DISPOSAL OF THIS SCRIPT COPY DOES NOT ALTER ANY OF THE RESTRICTIONS SET FORTH ABOVE. TITLES UP: San Francisco, 1978. The words dissolve, and we hold on blackness. Hear soft eerie wind chimes. CUT TO: EXT. HOUSE -- AFTERNOON PUSH across a leaf-strewn lawn to find a GIRL, eight, with long braids, staring at an abandoned Victorian house that has fallen into grave disrepair. Shutters missing, paint peeling...an ingenue turned dowager by the march of time. Suddenly, a rock whizzes by the girl’s head and SHATTERS an upper story window. She turns and we finally SEE her face. This is ADELAIDE, and she has Down Syndrome. TWO BOYS, TEN, bash a gate open with a baseball bat and strut into the yard. This is Troy and Bryan...the Rutger twins. TROY Hey, retard. They head into the empty derelict house, on a mission. Adelaide suddenly speaks. ADELAIDE Excuse me. They stop, turn. ADELAIDE (CONT’D) You’re going to die in there. They stare at her a beat, the moment is shocking. Then Troy runs to her, viciously pushes her to the ground. He regards her, spits on her, then heads back into the house. -

Representation of Abortion in Selected Film and Television

REPRESENTATION OF ABORTION IN SELECTED FILM AND TELEVISION Claire Ann Barrington Supervisor: Michael Titlestad A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Johannesburg, 2016 i ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the representation of abortion provides a platform which reveals women’s societal and gendered positions, and provides a critique of the hypocritical attitudes to which societies subject women. I will be considering various representations of abortion in six films and two television shows. The films are Alexander Kluge’s Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave (1973), Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007), Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake (2004), Fruit Chan’s Dumplings (2004), The Pang Brother’s Re-Cycle (2006) and Ridley Scott’s Prometheus (2012). The two television shows are FX’s American Horror Story (2011—) and ABC’s Grey’s Anatomy (2005—). Each text provides a unique representation of abortion, often situating the issue within particular physical, social, political and cultural locations. In presenting a close reading of each text, I will show how the representation of abortion in each chapter relates to differing social, political and cultural ideologies. I will argue that there is a developing sense of the lived realities of women, which include, but are not limited to, issues of alienation, autonomy, agency and identity. Such lived realties, I will contend, are constructed within societies that, aware or not of the fact, are dominated by patriarchal influences. ii DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. -

American Horror Story" As Adaptation of E

"American Horror Story" as Adaptation of E. A. Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher" Mikolčić, Monika Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2019 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:177051 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i hrvatskoga jezika i književnosti Monika Mikolčić "Američka horor priča" kao adaptacija "Pada kuće Usherovih" E. A. Poea Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i hrvatskoga jezika i književnosti Monika Mikolčić "Američka horor priča" kao adaptacija "Pada kuće Usherovih" E. A. Poea Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2019. J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Croatian Language and Literature Monika Mikolčić American Horror Story as Adaptation of E. A. Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher" Bachelor's Thesis Supervisor: Ljubica Matek, Ph.D. Assistant Professor Osijek, 2019 J.J. -

Nomination Press Release

Brad Walsh, Executive Producer Outstanding Comedy Series Jeff Morton, Co-Executive Producer The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Jeffery Richman, Co-Executive Producer Productions, Inc. in association with Warner Abraham Higginbotham, Co-Executive Producer Bros. Television Cindy Chupack, Co-Executive Producer Chuck Lorre, Executive Producer Chris Smirnoff, Producer Bill Prady, Executive Producer Steven Molaro, Executive Producer 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Dave Goetsch, Co-Executive Producer Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Television Eric Kaplan, Co-Executive Producer Lorne Michaels, Executive Producer Jim Reynolds, Co-Executive Producer Tina Fey, Executive Producer Peter Chakos, Supervising Producer Robert Carlock, Executive Producer Steve Holland, Supervising Producer Marci Klein, Executive Producer Maria Ferrari, Producer David Miner, Executive Producer Faye Oshima Belyeu, Produced By Jeff Richmond, Executive Producer Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO John Riggi, Executive Producer Entertainment Ron Weiner, Co-Executive Producer Larry David, Executive Producer Matt Hubbard, Co-Executive Producer Jeff Garlin, Executive Producer Kay Cannon, Supervising Producer Gavin Polone, Executive Producer Vali Chandrasekaran, Supervising Producer Alec Berg, Executive Producer Josh Siegal, Supervising Producer David Mandel, Executive Producer Dylan Morgan, Supervising Producer Jeff Schaffer, Executive Producer Luke Del Tredici, Supervising Producer Larry Charles, Executive Producer Jerry Kupfer, Producer Tim Gibbons, Executive -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

"Amped About Hell": Representations of the Suburban Gothic in Serial Television Simone Marjorie Perry Lake Forest College, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lake Forest College Publications Lake Forest College Lake Forest College Publications Senior Theses Student Publications 4-28-2014 "Amped About Hell": Representations of the Suburban Gothic in Serial Television Simone Marjorie Perry Lake Forest College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://publications.lakeforest.edu/seniortheses Part of the American Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Perry, Simone Marjorie, ""Amped About Hell": Representations of the Suburban Gothic in Serial Television" (2014). Senior Theses. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Amped About Hell": Representations of the Suburban Gothic in Serial Television Abstract Derived from the work of Bernice M. Murphy, "Suburban Gothic" is a subgenre in popular culture providing continuous commentary on American society. Though she writes extensively about depictions of Suburban Gothic throughout the last several decades, Murphy’s research has shown little interest in television. The advent of complex narrative in serial television, particularly over the last twenty-five years, is crucial to homing in on the format. Viewing the Suburban Gothic as a "genre television,” we can see it evolving into a higher art form. Using essays in aesthetics and film theory to enhance the understanding of Suburban Gothic, three shows are using a combination of these theories. -

Women, Theory and Horror Film

Gynaehorror: Women, theory and horror film A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Studies in the University of Canterbury by Erin Harrington University of Canterbury March 2014 ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................... v ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................ vii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................... viii INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................ 1 (RE)CONCEPTIONS: THEORISING WOMEN IN HORROR ................................................... 16 Horror and psychoanalysis .................................................................................................................. 18 Women, horror and psychoanalysis ................................................................................................. 23 Challenges to psychoanalysis .............................................................................................................. 31 Alternatives to psychoanalysis: the social, the mythic, the taboo ........................................ 36 From theories of horror to theorising with horror ................................................................... -

Mother Monster Checks Into Ter Checks Into Hotel

MOTHER MONSTER CHECKS INTO HOTEL Lady Gaga with Lennon Henry, Cannon Mosteller, and Emmory Mosteller photographed exclusively for EW by Michael Avedon on the set of American Horror Story: Hotel on Aug. 12, 2015, in Los Angeles FEEDING HER TASTE FOR THE MACABRE, LADY GAGA HEADLINES THE TWISTED NEW SEASON OF AMERICAN HORROR STORY: HOTEL. IN THIS EXCLUSIVE FIRST LOOK, WE LEARN THAT IN PLAYING A BRUTAL BUT GLAM BLOODSUCKER, THE BOUNDARY- PUSHING STAR ATTACKS THE CHALLENGE WITH ABSOLUTELY NO RESERVATIONS. 23 PHOTOGRAPHS BY MICHAEL AVEDON BY TIM STACK CLOCKWISE FROM FAR LEFT ◆ Finn Witrock; Lady Gaga and Matt Bomer; Evan Peters; Max Greenfield; Christine Estabrook, Cheyenne Jackson, and Lyric Lennon; Angela Basset (PREVIOUS SPREAD) STYLING: LOU EYRICH; ASSISTANT STYLISTS: ROBERT SPARKMAN AND AND SPARKMAN ROBERT STYLISTS: EYRICH; ASSISTANT STYLING:(PREVIOUS SPREAD) LOU IS IT A TRUE FOURSOME IF HALF THE SANDRA AMADOR; HAIR: FREDERIC ASPIRAS/THE ONLY AGENCY AND MONTE C. HAUGHT; a sock covering his junk, goes first, with co- has fueled the soundstage with a giddy, MAKEUP: SARAH TANNO/THE WALL GROUP, ERYN KRUEGER MEKASH, AND LOU EYRICH; sexual participants are dead? This question creator and director Ryan Murphy calling REVEALED! surreal energy. Case in point: Her presence for the ages is being posed on a hot Monday out commands like “Stab! Feed!” Gaga sits attracts a visit from John Travolta, who is MORE LINKS BETWEEN evening on the Los Angeles set of American behind the monitors and watches like a HORROR STORY SEASONS shooting Murphy’s miniseries American Horror Story: Hotel. Lady Gaga, making her superfan.