University of Montevallo TRIO Mcnair Scholars Program 2018 Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Paraphilias

List of paraphilias Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association, in its Paraphilia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM), draws a Specialty Psychiatry distinction between paraphilias (which it describes as atypical sexual interests) and paraphilic disorders (which additionally require the experience of distress or impairment in functioning).[1][2] Some paraphilias have more than one term to describe them, and some terms overlap with others. Paraphilias without DSM codes listed come under DSM 302.9, "Paraphilia NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)". In his 2008 book on sexual pathologies, Anil Aggrawal compiled a list of 547 terms describing paraphilic sexual interests. He cautioned, however, that "not all these paraphilias have necessarily been seen in clinical setups. This may not be because they do not exist, but because they are so innocuous they are never brought to the notice of clinicians or dismissed by them. Like allergies, sexual arousal may occur from anything under the sun, including the sun."[3] Most of the following names for paraphilias, constructed in the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries from Greek and Latin roots (see List of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes), are used in medical contexts only. Contents A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z Paraphilias A Paraphilia Focus of erotic interest Abasiophilia People with impaired mobility[4] Acrotomophilia -

Table of Contents Abstract

Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………. …….. 2. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….. 3-5. Theoretical approaches………………………………………………………………………. 5-12. On reading Ryan Murphy’s critical creation(s)……………………………………………… 12-14. An analysis of the symbolical power present within the composition of the American nuclear family and how it is critiqued through its representation in American Horror Story: Murder House………………………………………………………………………………………… 14-62. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………… 62-64. Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………….. 65-66. 1 Abstract This Master’s Thesis is a psychoanalytical investigation into the critical interpretation of the traditional family practice taking place within contemporary American society as it is vividly mediated out to the viewing masses of the world by Ryan Murphy in his 2011 FOX series American Horror Story: Murder House. By making an individual analysis of each relevant episode with the theoretical propositions made by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud such as that of ‘the unconscious’, ‘the perceptive aspects of the primary and secondary processes’, ‘the repetition compulsion’, as well as the ‘final model of the mind’ and the theoretical composition of ‘the abject’ by philosopher Julia Kristeva readily at hand, this Master’s Thesis functions to bring a critique of how the American nuclear family remains an unchangeable product of its past sociological definition that places the validating notion of embodying the American (nuclear family) dream on a pedestal never to be obtainable to the desire driven psychological being of the American individual, who is indeed forever expected to pursue it, even in death. The main oppositional focus of the thesis is centered on sociologist George Peter Murdoch’s 1949 definition of ‘the nuclear family’ and its compatibility with the society in which it is expected to manifest itself by viewing it in the contextual framework of yet another cornerstone that can be found at the baseline of American society, one that is commonly known as the American dream. -

Representation of Abortion in Selected Film and Television

REPRESENTATION OF ABORTION IN SELECTED FILM AND TELEVISION Claire Ann Barrington Supervisor: Michael Titlestad A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts. Johannesburg, 2016 i ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the representation of abortion provides a platform which reveals women’s societal and gendered positions, and provides a critique of the hypocritical attitudes to which societies subject women. I will be considering various representations of abortion in six films and two television shows. The films are Alexander Kluge’s Part-Time Work of a Domestic Slave (1973), Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007), Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake (2004), Fruit Chan’s Dumplings (2004), The Pang Brother’s Re-Cycle (2006) and Ridley Scott’s Prometheus (2012). The two television shows are FX’s American Horror Story (2011—) and ABC’s Grey’s Anatomy (2005—). Each text provides a unique representation of abortion, often situating the issue within particular physical, social, political and cultural locations. In presenting a close reading of each text, I will show how the representation of abortion in each chapter relates to differing social, political and cultural ideologies. I will argue that there is a developing sense of the lived realities of women, which include, but are not limited to, issues of alienation, autonomy, agency and identity. Such lived realties, I will contend, are constructed within societies that, aware or not of the fact, are dominated by patriarchal influences. ii DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. -

WARNING! This Book Is Intended for ADULTS ONLY

WARNING! This book is intended for ADULTS ONLY. If you are easily offended you do not want to purchase this product. If you are hard to offend you still may not want to buy this product! (I’m serious; we have plenty of other offerings for “mainstream” gamers.) This PDF is full of Hentai-inspired RPG rules, classes and setting elements; so if you would not purchase a Hentai product then this may not be your cup of tea. Consider yourself warned. Black TOKYOTOKYO ChastityChastity && DepravityDepravity Black Tokyo: Chastity & Depravity Written By: Chris A. Field Art by Anthony Cournoyer Nathan Winburn and Others Released by Otherverse Games in conjunction with Skortched Urf’ Studios For Mature Audiences Only. Black Tokyo: Chastity and Depravity Byakko Medium Humanoid (Shapechanger) Black Tokyo began as a passing whim, evolved into a complete gaming supplement, and somehow, against all The Byakko are named for the ‘tigers of the West’, a new the odds, became one of the best selling products ever species that takes its name from old Japanese myth. They released by either Skortched Urf Studios or the fledgling are a race drawn from the ranks of Black Tokyo’s young Otherverse Games. Despite the extreme subject matter, fetishists. The Byakko are Anglophile Japan, echhi Japan, adults only purchasing restrictions, Black Tokyo has yiffy Japan, furry fetishist Japan. They are living proof that sold… and sold… and sold some more. in Black Tokyo, desire can reshape human flesh and bone. This sourcebook serves as a continuation and expansion All Byakko are born human, but abandon their human forms of the Black Tokyo world, delving even deeper into this sometime before their 16th birthday. -

Involuntary Females -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

Involuntary Females by eighthdwarf2002 Part 2: Emily 1 2 Disclaimer: This is a story about body transformation into other shapes, including gender. It contains scenes of bondage and other things which are not suitable for minors. This entire series is a work of pure fiction, although inspired by a lot of other stories written by talented authors. All institutions, people and situations are fictitious, and any similarity to real institutions, people and situations is purely coincidental. So have fun reading my musings - hope you like it. eighthdwarf2002 Thanks to all who inspired and helped me to write this story. And special thanks to Ed K. You know why. "Copyleft - All rites reversed." 3 Author's Note to Part 2: Here is the second part of the story, telling the tale of Jona's aunt Emily Miller M.D., now MLE 1.1 Why does she bear that technical name now, and what else has she gone through before? - Well, read her story to find out. 4 Chapter 1: Excerpts from the Diary Chapter 1: Excerpts from the Diary Chapter 1: Excerpts from the Diary 1.1 A Brief Introduction My name is Emily Miller. Well, that's not quite true, now. That was my name before I became the android MLE 1.1. Many of my fans have asked me about my life, and I have tried to write down my memories to the best of my ability. I have not always been female, and I have not always been lesbian as I am now. I was born as the first child of the Banker, Samuel Schweitzer, and his first wife Vanessa, but not as a girl: my birth- name was Eric John Schweitzer. -

Inside the Pleasure Dome Fringe Film in Canada

Everybody loves the movies. But what of movies made about the colour blue, or an isolated mountain range, or a man grown so thin the world floats through his perfect transparency? “You know what would be really great — to make a two-hour movie about Taylor Mead’s ass.” So said Andy Warhol, the most notorious fringe filmer of them all. Welcome to the strange and wonderful microverse of fringe cinema, where the only rules left unbroken are the ones that have been forgotten. Long before MTV, these artists were bending light to make a strange, first-person possible. This new edition features never-before-heard raps from Ellie Epp, Ann Marie Fleming, Chris Gallagher, Anna Gronau, Rick Hancox, John Kneller, Deirdre Logue, David Rimmer and Kika Thorne. They join fellow fringers Mike Snow, Carl Brown, Patricia Gruben, Barbara Sternberg, Al Razutis, Penelope Buitenhuis, Fumiko Kiyooka, Peter Lipskis, Wrik Mead, Annette Mangaard, Steve Sanguedolce, Gary Popovich, Philip Hoffman, Gariné Torossian, Richard Kerr, and Mike Cartmell. Twenty-five interviews with Canada’s finest underdogs lay it all down like a road, ready to take you through the vanishing point of personality. This is cinema made one frame at a time, truth twenty-four times a second, as one wag would have it, a cinema that is earned and lived before being bigged up into the projector light. These lives have each developed an eccentric attention, a way of seeing the world that is able to transform something you walk past every day into something strange and terrifying. For any who wondered what lay beyond the McCinemas, the monotone of multiplex occupations, here are the stars of a different kind of night. -

A Contemporary Rejuvenation of the Biji

Staying Alive: A Contemporary Rejuvenation of the Biji A Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy To the Department of Communications In the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at The University of Technology Sydney 2015 By Dave Drayton Primary Supervisor: Dr Sue Joseph 1 2 Certificate Of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Dave Drayton Date: 20/08/2015 3 Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the help of the following people: Sue Joseph, for guiding me through Honours and into post-graduate study, being a resounding sounding board, and a source of energy when it all seemed too much. Jo and Nicky, for encouraging and facilitating my love of learning and this gargantuan undertaking. Dr Jack George James Rudi McLean Tsonis, for his support and encouragement from within the deep height of the Atterton Academy. Justine Keating, for her patience and support. The following people and institutes were also extremely helpful in their suggestions, recommendations, clarifications, translations, and inspiration: Tim Kinsella, Dr Esther Klein, Daniel Levin Becker, Chinese Studies Association of Australia, Marcel Benabou, Dr Carrie Reed, James Mackay. -

Inhoudstafel

2 Inhoudstafel 1. Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 5 2. Voorwoord ......................................................................................................................... 6 3. Inleiding ............................................................................................................................. 7 4. Literatuurstudie ............................................................................................................... 9 4.1. Genrebenadering .......................................................................................................... 9 1.1.1. Genre en televisie ............................................................................................... 11 1.1.2. Horrorgenre: theorievorming ............................................................................. 11 1.1.3. Horror: Maatschappijkritiek ............................................................................... 14 1.1.4. Horror: Stijlkenmerken ...................................................................................... 15 4.2. TV Horror .................................................................................................................. 17 4.3. Literatuurstudie: besluit ............................................................................................. 20 5. Methodologie .................................................................................................................. -

Who's Afraid of the Rubber Man? Perversions and Subversions Of

Volume 5, Issue 2 September 2012 Who’s Afraid of the Rubber Man? Perversions and Subversions of Sex and Class in American Horror Story TOSHA TAYLOR, Loughborough University ABSTRACT This article examines representations of sexuality in the first series of American Horror Story. Though the series presents many supernatural villains and is, on the surface, a typical haunted house story, it often creates its sense of horror through deployment of sexual tropes. The haunted house story itself is traditionally linked to notions of sexuality and class (Bailey, 1999; Ellis, 1989); this paper argues that American Horror Story (2011- ) emphasizes that link and manipulates such notions to explore their place in contemporary American thought and entertainment. Analysis of Kristeva’s and Creed’s linking of Horror to sexuality demonstrates that the series builds its sense of horror on abjection. Ghosts and other supernatural creatures in the series, this article contends, are merely accoutrements to a plot that is steeped in sexual anxieties. Grounded in Foucault’s characterization of sanctioned sexual repression as ‘a sentence to disappear’ and ‘an injunction to silence’ (Foucault, 1978: 4), this discussion of American Horror Story studies the show’s explicit references to, and depictions of, sexual practices that are typically neglected on mainstream television. Finally, this article questions the show’s success in subverting popular opinions about aberrant sexualities. KEYWORDS American Horror Story, BDSM, Gothic fiction, haunted house, Horror, queer television, sexuality, Telefantasy Though programs boasting Science Fiction and Fantasy elements seem far more numerous, primetime television in the US has not avoided Horror. Shows like Twin Peaks (1990-1991) and The X-Files (1993-2002) still enjoy a niche viewership, and even Dr. -

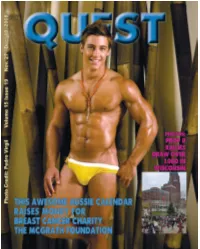

Quest Magazine Vol 15 Issue 19

PROPOSITION 8 PROTESTS IN WISCONSIN DRAW OVER 1,000 Rallies Held in Appleton, Eau Claire, Green Bay, La Crosse, Madison, Milwaukee and Superior-Duluth Statewide - Despite gray skies with wind chills in Fair Wisconsin will stepped off from the University of the teens, more than 1,000 LGBT community mem - Wisconsin library mall and proceed to the State Capi - bers and allies in seven cities including Appleton, Eau tol. Marcher Tim Schlichting counted 417 present. Claire, Green Bay, LaCrosse, Madison, Milwaukee, and Sarah Korpi, a UW-Madison graduate student who Superior-Duluth participated in the national protest had flown to California to marry her partner only against the passage of Proposition 8 in Wisconsin months ago, captured the contrast many gay people November 15. felt on election Day. “So it’s still okay to hate us,” Gay furor over the passage of California’s Proposition she told reporter Shawn Doherty of The Capital Times . 8 rescinding the right of gay and lesbian couples to “Everybody was celebrating the election of Barack marry spread beyond that state’s borders with tens of Obama and change, but we felt so left out.” thousands involved in an estimated 500 rallies and Milwaukee activists rallied in Arrow Head Park after marches organized by an ad hoc Seattle-based group marching from the Milwaukee City Hall building. The called “Join The Impact.” The “Fight The H8” events event drew about 400 people, according to Kurt Dyer occurred simultaneously across the United States. The of Center Advocates. Other estimates of the Milwau - Join The Impact website listed links to rallies in every kee rally ranged from 200-300. -

George Henry Longly the Tissue Equivalent in the Sensitive Fabric of Perceptions

Essays by ADÉLAÏDE BLANC MILOVAN FARRONATO LUCIA PIETROIUSTI Portrait by TINTIN JONSSON GEORGE HENRY LONGLY THE TISSUE EQUIVALENT IN THE SENSITIVE FABRIC OF PERCEPTIONS One of the strategies employed by the artist George Henry Longly to question pre- sentation systems, be they commercial, museographic or scenic, consists in “pro- ducing breaks in the sensitive fabric of perceptions and in the dynamics of sensa- tions.”1 As a result, in his installations, the presentation and the devices directing the gaze are manipulated and corrupted. In The Smile of a Snake (Valentin, Paris, 2016), Longly questions the very nature of the exhibition, the staging of which cre- ates a virtual image that recalls a 3D simulation in its appearance. As soon as we enter the exhibition, the physical reality of the gallery fades into an installation that is nevertheless fully perceived through sight, hearing and smell. The performance Parks Night (Serpentine, London, 2013) reproduces and distorts with irony the co- des of the fashion show. The presentation of the clothes disappears, shifting the focus onto bodies and poses, the true protagonists of a choreography positioned halfway between fashion, advertising, and the performative aspects that our lives can have. The artist continues his exploration of presentation strategies with a personal exhi- bition at the Palais de Tokyo, which he describes as a “4D exhibition experience.” Traversed by a liminal movement, the installation skirts and changes while it is being perceived. The lighting, the sound and the set up devices appear to be ani- mated by an aleatory mechanism that innervates a space undergoing movements of retraction and expansion. -

The Representations of Rape in American Horror Story

THE HORROR OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE: THE REPRESENTATIONS OF RAPE IN AMERICAN HORROR STORY by Trevor Myrick A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The University of Utah In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Degree in Bachelor of Arts In College of Fine Arts Department of Art & Art History Approved: ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Lela Graybill Brian Snapp Faculty Supervisor Chair, Dept. Art & Art History ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Paul Monty Paret Dr. Sylvia D. Torti Department Honors Advisor Dean, Honors College May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This thesis looks at the representation of rape in American Horror Story, considering its formal and narrative construction alongside critical responses, drawing attention to both innovative and stereotypical aspects of its function within the series. While the series generally revels in representing explicitly violent and abject topics through fantasy and the employment of various horror elements, it also incorporates representations of rape with remarkable frequency. In its first three seasons, the series integrated rape narratives a whopping eleven times within 38 episodes, with each new episode of American Horror Story thus having a nearly 29% chance of representing rape or sexual assault in some way. The pervasiveness of rape in American Horror Story is undeniable, yet little to no critical discourse examines its continual use and subsequent impact on conversations surrounding rape culture. While other popular and current television series’ singular inclusions of rape narratives—such as Downton Abbey, Scandal, Mad Men, etc.—have been widely discussed by critics and fans alike, the representation of rape in American Horror Story remains largely unnoted.