Textbook of Gregorian Chant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDELINES for CONCERTS in CHURCH DIOCESE of HARRISBURG Office of Worship

GUIDELINES FOR CONCERTS IN CHURCH DIOCESE OF HARRISBURG Office of Worship BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION The Church holds a vast and wonderful treasure of sacred and religious music that continually lifts the mind and heart to God. Sacred music, whether vocal or instrumental, has an integral place in our history and worship. The recent documents of Vatican II, namely, the Constitution on the Liturgy Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Instruction Musicam Sacram, the Instruction Liturgicae Instauratione, as well as the prescriptions of the Code of Canon Law, Canons 1210, 1213 and 1222 treat of the integrity and importance of music in the life of the Church. Some types of sacred music do not always have a proper place within the liturgical celebration. Gounod’s “Sanctus” from the Mass of Saint Cecilia is certainly a beautiful and spiritually moving piece, but no longer has a place during the Sunday Mass. It is not only lengthy but does not allow for the active participation of the faithful during the prominent acclamation. The “Gloria” by John Rutter, a contemporary composer and conductor, another marvelous piece of sacred music, would not have an appropriate place in the liturgy because of its length (more than seventeen minutes). Yet such magnificent music deserves to be fostered and preserved. This is done not only in recordings, but also in concerts held in public places. The increase in the number of concerts in general has given rise to a more frequent use of churches for such events. Churches are considered to be in many ways apt places for holding a concert especially because of their size, acoustics, aesthetics and even practicality (e.g., as facilities for organ recitals). -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

Why We Sing What We Sing and Do What We Do at Mass Looking for Ways to ENGAGE Your Assembly?

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION of PASTORAL MUSICIANS PASTORAL May 2010 Music Why We Sing What We Sing and Do What We Do at Mass Looking for ways to ENGAGE your assembly? ENGAGE UNITE OCP missals give you music known and loved by Catholics around the world, helping you connect with your parishioners and inspire your community. Discover how the right missal program can enhance INSPIRE your worship experience—Call us today! WORSHIP 1-866-728-2209 | ocp.org NPM-May2010:Layout 1 3/17/10 2:56 PM Page 1 Peter’s Way Tours Inc. Specializing in Custom Performance Tours and Pilgrimages Travel with the leader, as choirs have done for 25 years! Preview a Choir Tour! This could be ROME, FLORENCE, ASSISI, VATICAN CITY your choir in Rome! Roman Polyphony FEBRUARY 17 - 24, 2011 • $795 (plus tax) HOLY LAND - Songs of Scriptures FEBRUARY 24 - MARCH 5, 2011 • $1,095 (plus tax) IRELAND - Land of Saints and Scholars MARCH 1 - 7, 2011 • $995/$550* (plus tax) Continuing Education Programs for Music Directors Enjoy these specially designed programs at substantially reduced rates. Fully Refundable from New York when you return with your own choir! *Special Price by invitation to directors bringing their choir within 2 years. Visit us at Booth #100 at the NPM Convention in Detroit 500 North Broadway • Suite 221 • Jericho, NY 11753 New York Office: 1-800-225-7662 Special dinner with our American and Peter’s Way Tours Inc. EuropeanRequest Pueria brochure: Cantores [email protected] groups allowing for www.petersway.com or call Midwest Office: 1-800-443-6018 From the President Dear Members, fourth and fifth centuries, such as Ambrose, Augustine, Cyril of Jerusalem, and John Chrysostom. -

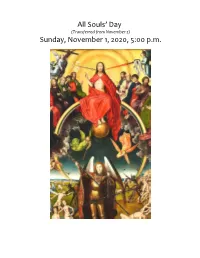

2020-11-01 Gregorian Chant, Preliminary

All Souls’ Day (Transferred from November 2) Sunday, November 1, 2020, 5:00 p.m. ALL SOULS’ DAY/ALL SOULS’ REQUIEM The tradition of observing November 2 as a day of commemoration began in the tenth century as a complement to All Saints’ Day, November 1. The traditional service of remembering the dead — whether on this day or during an actual funeral — is called a Requiem, the first word of the Latin text, meaning “rest.” The solemnity of the liturgy and the beauty of the music help us to mourn with hope. Thus we are encouraged to trust ever more in God’s gift of eternal life through the death and resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. THE GREGORIAN CHANT REQUIEM The oldest musical setting of the Requiem is the version in Gregorian Chant (plainsong, melody only, no harmony). Created sometime in the first millennium A.D., it does have one “new” movement, the Dies irae, dating from no later than the 1200s. The Dies irae melody has been quoted in non-Requiem music by Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Camille Saint-Saëns, among others. Some composers of Requiem settings have omitted the Dies irae text, either because of its length or because of its expression of fear, guilt, and judgment. Regarding the latter issue, Jesus, his apostles, and his Hebrew prophets do indeed declare a day of reckoning, and fear is a legitimate human feeling, expressed in the Psalms and in the Prophets. However, God’s grace can ease our fear, and — through the Holy Spirit’s ministry — can offset it by giving us confidence in Christ’s merit rather than our own. -

Introitus: the Entrance Chant of the Mass in the Roman Rite

Introitus: The Entrance Chant of the mass in the Roman Rite The Introit (introitus in Latin) is the proper chant which begins the Roman rite Mass. There is a unique introit with its own proper text for each Sunday and feast day of the Roman liturgy. The introit is essentially an antiphon or refrain sung by a choir, with psalm verses sung by one or more cantors or by the entire choir. Like all Gregorian chant, the introit is in Latin, sung in unison, and with texts from the Bible, predominantly from the Psalter. The introits are found in the chant book with all the Mass propers, the Graduale Romanum, which was published in 1974 for the liturgy as reformed by the Second Vatican Council. (Nearly all the introit chants are in the same place as before the reform.) Some other chant genres (e.g. the gradual) are formulaic, but the introits are not. Rather, each introit antiphon is a very unique composition with its own character. Tradition has claimed that Pope St. Gregory the Great (d.604) ordered and arranged all the chant propers, and Gregorian chant takes its very name from the great pope. But it seems likely that the proper antiphons including the introit were selected and set a bit later in the seventh century under one of Gregory’s successors. They were sung for papal liturgies by the pope’s choir, which consisted of deacons and choirboys. The melodies then spread from Rome northward throughout Europe by musical missionaries who knew all the melodies for the entire church year by heart. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Psalms to Plainchant: Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1989 Psalms to Plainchant: Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France Caroline Beth Kunkel College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Recommended Citation Kunkel, Caroline Beth, "Psalms to Plainchant: Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France" (1989). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625537. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-874z-r767 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PSALMS TO PLAINCHANT Seventeenth-Century Sacred Music in New England and New France A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Caroline B. Kunkel 1989 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Caroline B. Kunkel Approved, May 1990 < 3 /(yCeJU______________ James Axtell A )ds Dale Cockrell Department of Music (IlliM .d (jdb&r Michael McGiffertA / I All the various affections of our soul have modes of their own in music and song by which they are stirred up as by an indescribable and secret sympathy. - St. Augustine Sermo To my parents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........ -

Diocesan Commissions for Liturgy, Music, and Art: Knowing the Past to Prepare for the Future

Diocesan Commissions for Liturgy, Music, and Art: Knowing the Past to Prepare for the Future by the Reverend Monsignor John J. M. Foster, J.C.D. Vicar General and Moderator of the Curia for the Archdiocese for the Military Services, USA In the fifth chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, the evangelist tells us that, after seeing the crowds, Jesus went up the mountain. His disciples came to him, and he began teaching them (Mt 5:1–2). After the Beatitudes, Jesus presented the sayings on salt and light, which Daniel Harrington tells us, “serve to define the identity of those who follow Jesus faithfully.”1 You are the salt of the earth. But if salt loses its taste, with what can it be seasoned? It is no longer good for anything but to be thrown out and trampled underfoot. You are the light of the world. A city set on a mountain cannot be hidden. Nor do they light a lamp and then put it under a bushel basket; it is set on a lampstand, where it gives light to all in the house” (Mt 5:13–15, RNAB). As followers of the Lord Jesus who have been baptized into his passion, death, and resurrection, we are the salt of the earth and light of the world. To be salt and light, especially in today’s world, is a challenge for any Christian, but for us who have taken on diocesan and parochial responsibilities for promoting the liturgical life in our particular churches, Jesus’ teaching provides additional challenges. Given the seemingly endless number of liturgies to prepare, the constant barrage of phone calls and emails from the Christian faithful yearning to have their questions answered, and growing piles of articles and books to read to keep up-to-date on sacramental and liturgical issues, members of diocesan commissions for liturgy, music, and art and worship office staff members might understandably feel like salt that has lost its taste. -

Liturgical Music in Anglican Benedictine Monasticism

LITURGICAL YUSIC , Tn Anglican CZ3enedictine;, Monasticism DOM DAVID NICHOLSON, O.S.B. Monk of Mount Angel Abbey, Oregon U.S.A. Contents Introduction 5 Elmore Abbey (Formerly Nashdom Abbey), Berks, England 7 Alton Abbey, Hants, England 9 St. Gregory's Abbey, Three Rivers, Michigan, U.S A 10 St. Mark's Priory, Camperdown, Victoria, Australia 12 Edgware Abbey, Middlesex, England 15 St. Mary's Abbey,Kent, England 16 Burford Priory, Oxon, England 18 Holy Cross Convent, Rempstone, England 20 St. Hilda's Priory, Sneaton Castle, Whitby, N. Yorkshire, England 24 Community of St. Peter the Apostle, Glos. England 26 St. Peter's Convent, Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England 27 Order of the Holy Cross, Berkeley, California, U.S A 29 Ewell Monastery, West Mailing, Kent, England (Cistercian) 31 For Burnham (House of Prayer) Slough, England (Cistercian) 32 Russell Savage, Assistant Organist, St. James (Anglican) Church, Vancouver, British Columbia. Assistant Organist, Westminster Abbey, Mission, British Columbia, Canada. ©1990 Mount Angel Abbey, St. Benedict Oregon 97373 Introduction This volume follows, in natural sequence, the series: Liturgical Music in andBenedictine women in Monasticism. the Canterbury Although Communion there are which not a great base numbertheir life of on monasteries the Rule of St. of men Benedict, they are a witness to the monastic calling. in severalEach cases,Monastery where was I was asked not ableto explain to compile its historical sufficient and information liturgical modus I gathered vivendi, this from but GordonThe Benedictine Beattie, O.S.B., and CistercianR.A.F., monk Monastic of Ampleforth Yearbook (1990) Abbey. edited by Rev. Dom I wish to thank all who contributed to this work. -

Gregorian Chant, a Textbook for Seminaries, Novitiates And

^» «»»» * » » » 3 » Please handle this volume with care. The University of Connecticut Libraries, Storrs Music MT K6 C-7 MUSIC LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT §TQRRS, CONNECTICUT MUSIC LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT 8T0RRS, CONNECTICUT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/gregorianchantteOOklar GREGORIAN CHANT GREGORIAN CHANT A TEXTBOOK FOR SEMINARIES, NOVITIATES AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS MUSIC LIBRARY CUI ONWER^OFCON CONHECTICUIS STORRS. by REV. ANDREW F. KLARMANN Teacher of Music Cathedral College, Brooklyn, N. Y. Published by GREGORIAN INSTITUTE OF AMERICA TOLEDO, OHIO Imprimatur *MOST REV. THOMAS E. MOLLOY, S.T.D. ~* Bishop of Brooklyn * i Nihil Obstat REV. JOHN F. DONOVAN^ Censor Ltbrorum JANUARY 27, 1945 Desclee and Company of Tournai, Belgium, has granted permission to the author to use the rhythmic marks in this textbook. Copyright, 1945, by Gregorian Institute printed in u.s.a. all rights reserved Dedicated to MOST REVEREND THOMAS E. MOLLOY Bishop of Brooklyn FOREWORD In the following pages Father Klarmann presents a clear, orderly, systematic treatment of liturgical chant. At the very beginning of his treatise he provides an explanation of certain fundamental terms, such as notation, signs, rhythm, chant structure, etc., which is very serviceable in preparing the reader for the fuller development of the general theme in the sub- sequent chapters of this book. With the same thought and purpose the author more particu- larly gives an early definition of the chief subject of discussion, namely, chant, which he defines, in the usually accepted sense, as liturgical music in the form of plain song, which is monophonic, unaccompanied and free in rhythm. -

The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music After the Revolution

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2013-8 The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, D. (2013) The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D76S34 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly, BA, MA, HDip.Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr David Mooney Conservatory of Music and Drama August 2013 i I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate study by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for another award in any other third level institution. -

Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theology Papers and Journal Articles School of Theology 2007 Classified timelines of ernacularv liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy Russell Hardiman University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article Part of the Religion Commons This article was originally published as: Hardiman, R. (2007). Classified timelines of vernacular liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy. Pastoral Liturgy, 38 (1). This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article/9. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classified Timelines of Vernacular Liturgy: Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy Russell Hardiman Subject area: 220402 Comparative Religious Studies Keywords: Vernacular Liturgy; Pastoral vision of the Second Vatican Council; Roman Policy of a single translation for each language; International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL); Translations of Latin Texts Abstract These timelines focus attention on the use of the vernacular in the Roman Rite, especially developed in the Renewal and Reform of the Second Vatican Council. The extensive timelines have been broken into ten stages, drawing attention to a number of periods and reasons in the history of those eras for the unique experience of vernacular liturgy and the issues connected with it in the Western Catholic Church of our time. The role and function of International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL) over its forty year existence still has a major impact on the way we worship in English. This article deals with the restructuring of ICEL which had been the centre of much controversy in recent years and now operates under different protocols.