Material Culture and Cultural Memory After the English Reformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

The Latin Mass Society

Ordo 2010 Compiled by Gordon Dimon Principal Master of Ceremonies assisted by William Tomlinson for the Latin Mass Society © The Latin Mass Society The Latin Mass Society 11–13 Macklin Street, London WC2B 5NH Tel: 020 7404 7284 Fax: 020 7831 5585 Email: [email protected] www.latin-mass-society.org INTRODUCTION +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Omnia autem honeste et secundum ordinem fiant. 1 Cor. 14, 40. This liturgical calendar, together with these introductory notes, has been compiled in accordance with the Motu Proprio Rubricarum Instructum issued by Pope B John XXIII on 25th July 1960, the Roman Breviary of 1961 and the Roman Missal of 1962. For the universal calendar that to be found at the beginning of the Roman Breviary and Missal has been used. For the diocesan calendars no such straightforward procedure is possible. The decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites of 26th July 1960 at paragraph (6) required all diocesan calendars to conform with the new rubrics and be approved by that Congregation. The diocesan calendars in use on 1st January 1961 (the date set for the new rubrics to come into force) were substantially those previously in use but with varying adjustments and presumably as yet to re-approved. Indeed those calendars in use immediately prior to that date were by no means identical to those previously approved by the Congregation, since there had been various changes to the rubrics made by Pope Pius XII. Hence it is not a simple matter to ascertain in complete and exact detail the classifications and dates of all diocesan feasts as they were, or should have been, observed at 1st January 1961. -

T He Journal of Ecclesiastical History

00220469_69-2_00220469_69-2 26/03/18 3:36 PM Page 1 The Journal ofThe Journal Ecclesiastical History 69 The Journal of Ecclesiastical History Vol. No. 2 April 2018 Volume 69 Number 2 April 2018 CONTENTS i ARTICLES Who was Arnobius the Younger? Dissimulation, Deception and Disguise by a Fifth-Century Opponent of Augustine N. W. JAMES 243 The The Close Proximity of Christ to Sixth-Century Mesopotamian Monks in John of Ephesus’ Lives of Eastern Saints MATTHEW HOSKIN 262 Of Meat, Men and Property: The Troubled Career of a Convert Nun in Eighteenth-Century Kiev Journal LIUDMYLA SHARIPOVA 278 Anglicanism and Interventionism: Bishop Brent, The United States, and the British Empire in the First World War MICHAEL SNAPE 300 Vol. of Continuity and Change in the Luba Christian Movement, Katanga, Belgian Congo, c.1915–50 69 DAVID MAXWELL 326 No. 2 April 2018 NOTE AND DOCUMENT Richard Baxter, Thomas Barlow and the Advice to a Young Student in Theology, Ecclesiastical St John’s College, Cambridge, MS K.38: A Preliminary Assessment ROBERT DULGARIAN 345 REVIEW ARTICLE American Evangelical Politics before the Christian Right DANIEL K. WILLIAMS 367 History THE EUSEBIUS ESSAY PRIZE and THE WORLD CHRISTIANITIES ESSAY PRIZE 373 REVIEWS 374 BOOKS RECEIVED 468 AUTHORS’ ADDRESSES iv ® Cambridge Core MIX For further information about this journal Paper from please go to the journal website at: responsible sources cambridge.org/ech ® Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 02 Oct 2021 at 01:37:48, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use. 00220469_69-2_00220469_69-2 26/03/18 3:36 PM Page 2 The Journal of Ecclesiastical History Editors Copying James Carleton Paget, University of Cambridge This journal is registered with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Alec Ryrie, University of Durham Danvers, MA 01923, USA (www.copyright.com). -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Centre for Material Texts Annual Report 2014-15 Introduction The

centre for material texts annual report 2014-15 introduction The Cambridge Centre for Material Texts was constituted by the English Faculty Board in July 2009 to push forward critical, theoretical, editorial and bibliographical work in an increasingly lively field of humanities research. Addressing a huge range of textual phenomena and traversing disciplinary boundaries that are rarely breached by day-to-day teaching and research, the Centre fosters the development of new perspectives, practices and technologies, which will transform our understanding of the way that texts of many kinds have been embodied and circulated. This report summarizes the activities of the Centre in its sixth year. 2014-15 was a comparatively quiet year for the Centre, which meant that it was extremely rather than exceptionally busy. The History of Material Texts Seminar welcomed a lively mix of internationally renowned scholars and early-career academics; among many other things, we got a sneak preview of materials that William Zachs was preparing to use in his 2015 Rosenbach lectures in Philadelphia, and a foretaste from Leslie James of issues at stake in a conference on ‘Print Media in the Colonial World’ held at CRASSH in April 2015. The Medieval Palaeography Workshop, now in its fourth year, was joined by a series of seminars on Editing the Long Nineteenth Century. The CMT was among the sponsors of a one-day colloquium on Early Modern Visual Marginalia, and put together an exhibition in the Cambridge University Library in May 2015 which helped to publicize this and other recent research activities. A number of members of the Centre were involved in the major UL exhibition on Private Lives of Print: The Use and Abuse of Books 1450-1550, and contributed to the catalogue edited by Ed Potten and Emily Dourish. -

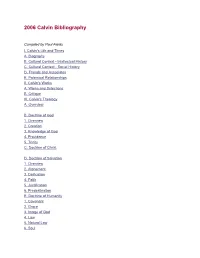

2006 Calvin Bibliography

2006 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul Fields I. Calvin's Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural Context Intellectual History C. Cultural Context Social History D. Friends and Associates E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin's Works A. Works and Selections B. Critique III. Calvin's Theology A. Overview B. Doctrine of God 1. Overview 2. Creation 3. Knowledge of God 4. Providence 5. Trinity C. Doctrine of Christ D. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Overview 2. Atonement 3. Deification 4. Faith 5. Justification 6. Predestination E. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Covenant 2. Grace 3. Image of God 4. Law 5. Natural Law 6. Soul 7. Free Will F. Doctrine of Christian Life 1. Angels 2. Piety 3. Prayer 4. Sanctification 5. Vows G. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline 3. Polity H. Worship 1. Overview 2. Buildings 3. Images 4. Liturgy 5. Mariology 6. Music 7. Preaching and Sacraments IV. Calvin and SocialEthical Issues V. Calvin and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Christian Life 2. Ecclesiology 3. Eschatology 4. Lord's Supper 5. Natural Law 6. Preaching 7. Predestination 8. Salvation 9. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Arts 2. Education 3. Literature 4. Printing C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. Croatia 2. England 3. Europe 4. France 5. Germany 6. Hungary 7. Korea 8. Latin America 9. Netherlands 10. Poland 11. Scotland 12. United States E. Critique F. Book Reviews G. Bibliographies I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography Cottret, Bernard. “Noms de lieux: Ignace de Loyola, Jean Calvin, John Wesley.” Études Théologiques et Religieuses 80, no. -

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents

Founded 1866 The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Monday: Miraculous Medal Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Therese Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) 8:00 a.m. (Tridentine Latin only during Lent) 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Devotions and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Vespers and Benediction: Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Saturday at 12:35 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. 10:30 a.m. -

Requiem Eucharist for the Commemoration of the Faithful Departed for All Souls’ Sunday 1 November 2020 3.00 Pm Welcome to St Edmundsbury Cathedral

Requiem Eucharist for the Commemoration of the Faithful Departed for All Souls’ Sunday 1 November 2020 3.00 pm Welcome to St Edmundsbury Cathedral In this afternoon’s All Souls’ Service we remember with thanksgiving the people we love who have died. The Commemoration of the departed on All Souls’ Day celebrates the saints in a more intimate way than All Saints’ Day. It allows us to remember with thanksgiving before God those whom we have known directly: those who gave us life, or who supported and encouraged us on life’s journey or who nurtured us in faith. In our worship, we sense that it is a fearful thing to come before the unutterable goodness and holiness of God, even for those who are redeemed in Christ; that it is searing as well as life-giving to experience God’s mercy. This instinct is expressed in the liturgy of All Souls’ Day. During this service, everyone is invited to bring the names of loved ones departed, written on the small white card crosses, to the cross before the altar, and to light a prayer candle there. Names will not be read aloud so that the total focus of this part of the liturgy may be on silent prayer and our individual commendation to God of those whom we remember but see no more. Music at today’s service The Cathedral Choir sings the Requiem, Op. 48 by Gabriel Fauré, 1845–1924. Service order extracts from Common Worship Services, © The Central Board of Finance of The Church of England. Music reproduced with permission - CCL Licence No 317297 ¶ The Order of Service As the choir and clergy gather at the west end of the Nave, the President welcomes the congregation from the Pavement, and then leads The Greeting President We meet in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. -

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700 Folger Shakespeare Library Spring Semester Seminar 2016 Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge): [email protected] The origins, impact and repercussions of the English Reformation have been the subject of lively debate. Although it is now widely recognised as a protracted process that extended over many decades and generations, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the links between the life cycle and religious change. Did age and ancestry matter during the English Reformation? To what extent did bonds of blood and kinship catalyse and complicate its path? And how did remembrance of these events evolve with the passage of the time and the succession of the generations? This seminar will investigate the connections between the histories of the family, the perception of the past, and England’s plural and fractious Reformations. It invites participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to explore how the religious revolutions and movements of the period shaped, and were shaped by, the horizontal relationships that early modern people formed with their sibilings, relatives and peers, as well as the vertical ones that tied them to their dead ancestors and future heirs. It will also consider the role of the Reformation in reconfiguring conceptions of memory, history and time itself. Schedule: The seminar will convene on Fridays 1-4.30pm, for 10 weeks from 5 February to 29 April 2016, excluding 18 March, 1 April and 15 April. In keeping with Folger tradition, there will be a tea break from 3.00 to 3.30pm. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Rene Matthew Kollar. Permanent Address: Saint Vincent Archabbey, 300 Fraser Purchase Road, Latrobe, PA 15650. E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 724-805-2343. Fax: 724-805-2812. Date of Birth: June 21, 1947. Place of Birth: Hastings, PA. Secondary Education: Saint Vincent Prep School, Latrobe, PA 15650, 1965. Collegiate Institutions Attended Dates Degree Date of Degree Saint Vincent College 1965-70 B. A. 1970 Saint Vincent Seminary 1970-73 M. Div. 1973 Institute of Historical Research, University of London 1978-80 University of Maryland, College Park 1972-81 M. A. 1975 Ph. D. 1981 Major: English History, Ecclesiastical History, Modern Ireland. Minor: Modern European History. Rene M. Kollar Page 2 Professional Experience: Teaching Assistant, University of Maryland, 1974-75. Lecturer, History Department Saint Vincent College, 1976. Instructor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1981. Assistant Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1982. Adjunct Professor, Church History, Saint Vincent Seminary, 1982. Member, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1981-86. Campus Ministry, Saint Vincent College, 1982-86. Director, Liberal Arts Program, Saint Vincent College, 1983-84. Associate Professor, History Department, Saint Vincent College, 1985. Honorary Research Fellow King’s College University of London, 1987-88. Graduate Research Seminar (With Dr. J. Champ) “Christianity, Politics, and Modern Society, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1987-88. Rene M. Kollar Page 3 Guest Lecturer in Modern Church History, Department of Christian Doctrine and History, King’s College, University of London, 1988. Tutor in Ecclesiastical History, Ealing Abbey, London, 1989-90. Associate Editor, The American Benedictine Review, 1990-94. -

Statutes and Ordinances of the University

CHAPTER IX FACULTIES, DEPARTMENTS, AND OTHER INSTITUTIONS UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF THE GENERAL BOARD The provisions contained in this Chapter are Regulations of the General Board GENERAL REGULATIONS FOR FACULTIES 1. There shall be a Faculty in respect of each of the subjects enumerated in the Schedule appended to these regulations. Preliminary 2. In October of every year, not later than the first day of Full Term, the Registrary shall publish a lists. preliminary list of the members of each Faculty. Objections. 3. Objections to the inclusion or omission of any name may be addressed to the Secretary of the Board of the Faculty concerned, and shall be decided by that Board subject to an appeal to the General Board. Any such decision of a Faculty Board or the General Board shall be communicated to the objector and to the Registrary forthwith. Corrected lists. 4. As early as possible in the Michaelmas Term each year, and in any case not later than 28 October, the Secretary of the Board of each Faculty shall send to the Registrary the names of persons who are members of the Faculty under Regulation 1(c) of the Regulations for Faculty Membership. Promulgation 5. On the fifth weekday of November the Registrary shall promulgate the lists of the Faculties, and of lists. the lists so promulgated shall constitute the several Faculties for the purpose of the annual meetings of Annual meetings. the Faculties. Those meetings shall be held after the sixth day and before the twenty-fifth day of November. Between the promulgation of the lists and the end of the academical year the Registrary shall not be required to ascertain or to notify any change that may occur in the membership of a Faculty. -

HO-35 Christ Church (Queen Caroline Parish Church)

HO-35 Christ Church (Queen Caroline Parish Church) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 02-07-2013 HO-35 Christ Episcopal Church "Old Brick," 6800 Oakland Mills Road Columbia vicinity Howard County, Maryland Private 1809 Description: Christ Episcopal Church, known as "Old Brick," is located on the west side of Oakland Mills Road in Columbia. The church is a one-story, two-bay by three-bay brick structure of 5 to 1 common bond with a rubble stone foundation that is now mostly below grade, and a gable roof with wood shingles and an east-west ridge. The brick has been sandblasted and was re-pointed in Portland cement with flush joints.