Finnegans' Wake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

A Psychological Study in James Joyce's Dubliners and VS

International Conference on Shifting Paradigms in Subaltern Literature A Psychological Study in James Joyce’s Dubliners and V. S. Naipaul’s Milguel Street: A Comparative Study Dr.M.Subbiah OPEN ACCESS Director / Professor of English, BSET, Bangalore Volume : 6 James Joyce and [V]idiadhar [S] Urajprasad Naipaul are two great expatriate writers of modern times. Expatriate experience provides Special Issue : 1 creative urges to produce works of art of great power to these writers. A comparison of James Joyce and V.S. Naipaul identifies Month : September striking similarities as well as difference in perspective through the organization of narrative, the perception of individual and collective Year: 2018 Endeavour. James Joyce and V.S. Naipaul are concerned with the lives of ISSN: 2320-2645 mankind. In all their works, they write about the same thing, Joyce write great works such as Dubliners, an early part of great work, Impact Factor: 4.110 and Finnegans Wake, in which he returns to the matter of Dubliners. Similarly, Naipaul has written so many works but in his Miguel Citation: Street, he anticipated the latest autobiographical sketch Magic Seeds Subbiah, M. “A returns to the matter of Miguel Street an autobiographical fiction Psychological Study in about the life of the writer and his society. James Joyce’s Dubliners James Joyce and V.S. Naipaul are, by their own confession, and V.S.Naipaul’s committed to the people they write about. They are committed to the Milguel Street: A emergence of a new society free from external intrusion. Joyce wrote Comparative Study.” many stories defending the artistic integrity of Dubliners. -

Of Finnegans Wake

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Pedagogy And Identity In "The Night Lessons" Of Finnegans Wake Zachary Paul Smola University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Smola, Zachary Paul, "Pedagogy And Identity In "The Night Lessons" Of Finnegans Wake" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 541. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/541 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! PEDAGOGY AND IDENTITY IN “THE NIGHT LESSONS” OF FINNEGANS WAKE A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree in the Department of English The University of Mississippi ZACHARY P. SMOLA May 2013 ! ! Copyright © 2013 by Zachary P. Smola All rights reserved ! ABSTRACT This thesis explores chapter II.ii of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939)—commonly called “The Night Lessons”—and its peculiar use of the conventions of the textbook as a form. In the midst of the Wake’s abstraction, Joyce uses the textbook to undertake a rigorous exploration of epistemology and education. By looking at the specific expectations of and ambitions for textbooks in 19th century Irish national schools, this thesis aims to provide a more specific historical context for what textbooks might mean as they appear in Finnegans Wake. As instruments of cultural conditioning, Irish textbooks were fraught with tension arising from their investment in shaping religious and political identity. -

James Joyce – Through Film

U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust A LEARNING OPTION FOR THE RETIRED Series 2 2015 James Joyce – Through Film Dates: Tuesday 2 June to 7 July Time: 10:00 – 12:00 noon Venue: Salmond College, Knox Street, North East Valley Enrolments for this course will be limited to 55 Course Fee: $40.00 Tea and Coffee provided Course Organiser: Alan Jackson (473 6947) Course Assistant: Rosemary Hudson (477 1068) …………………………………………………………………………………… You may apply to enrol in more than one course. If you wish to do so, you must indicate your choice preferences on the application form, and include payment of the appropriate fee(s). All applications must be received by noon on Wednesday 13 May and you may expect to receive a response to your application on or about 25 May. Any questions about this course after 25 May should be referred to Jane Higham, telephone 476 1848 or on email [email protected] Please note, that from the beginning of 2015, there is to be no recording, photographing or videoing at any session in any of the courses. Please keep this brochure as a reminder of venue, dates, and times for the courses for which you apply. JAMES JOYCE – THROUGH FILM 2 June James Joyce’s Dublin – a literary biography (50 min) This documentary is an exploration of Joyce’s native city of Dublin, discovering the influences and settings for his life and work. Interviewees include Robert Nicholson (curator of the James Joyce museum), David Norris (Trinity College lecturer and Chair of the James Joyce Cultural Centre) and Ken Monaghan (Joyce’s nephew). -

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce's Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL a Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingh

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce’s Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English Studies School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers the imbrications created by James Joyce in his writing with the work of John Milton, through allusions, references and verbal echoes. These imbrications are analysed in light of the concept of ‘presence’, based on theories of intertextuality variously proposed by John Shawcross, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, and Eelco Runia. My analysis also deploys Gumbrecht’s concept of stimmung in order to explain how Joyce incorporates a Miltonic ‘atmosphere’ that pervades and enriches his characters and plot. By using a chronological approach, I show the subtlety of Milton’s presence in Joyce’s writing and Joyce’s strategy of weaving it into the ‘fabric’ of his works, from slight verbal echoes in Joyce’s early collection of poems, Chamber Music, to a culminating mass of Miltonic references and allusions in the multilingual Finnegans Wake. -

Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-27, January 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.1.21-27 Ulysses: The Novel, the Author and the Translators Qing Wang Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—A novel of kaleidoscopic styles, Ulysses best displays James Joyce’s creativity as a renowned modernist novelist. Joyce maneuvers freely the English language to express a deep hatred for religious hypocrisy and colonizing oppressions as well as a well-masked patriotism for his motherland. In this aspect Joyce shares some similarity with his Chinese translator Xiao Qian, also a prolific writer. Index Terms—style, translation, Ulysses, James Joyce, Xiao Qian I. INTRODUCTION James Joyce (1882-1941) is regarded as one of the most innovative novelists of the 20th century. For people who are interested in modernist novels, Ulysses is an enormous aesthetic achievement. Attridge (1990, p.1) asserts that the impact of Joyce‟s literary revolution was such that “far more people read Joyce than are aware of it”, and that few later novelists “have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures.” Gillespie and Gillespie (2000, p.1) also agree that Ulysses is “a work of art rivaled by few authors in this or any century.” Ezra Pound was one of the first to recognize the gift in Joyce. He was convinced of the greatness of Ulysses no sooner than having just read the manuscript for the first part of the novel in 1917. -

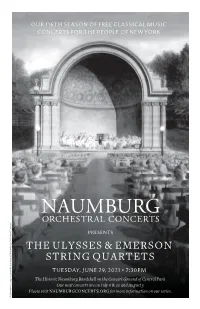

The Ulysses & Emerson String Quartets

OUR 116TH SEASON OF FREE CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM The Historic Naumburg Bandshell on the Concert Ground of Central Park Our next concerts are on July 6 & 20 and August 3 Please visit NAUMBURGCONCERTS.ORG for more information on our series. ©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing of Naumburg Orchestral of Naumburg Concert©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM In celebration of 116 years of Free Concerts for the people of New York City - The oldest continuous free outdoor concert series in the world Tonight’s concert is being hosted by classical WQXR - 105.9 FM www.wqxr.org with WQXR host Terrance McKnight NAUMBURG ORCHESTRAL CONCERTS PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS RICHARD STRAUSS, (1864-1949) Sextet from Capriccio, Op. 85, (1942) (performed by the Ulysses Quartet with Lawrence Dutton, viola and Paul Watkins, cello) ANTON BRUCKNER, (1824-1896) String Quintet in F major, WAB 112., (1878-79) Performed by the Emerson String Quartet with Colin Brookes, viola III. Adagio, G-flat major, common time -INTERMISSION- DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH, (1906-1975) Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11, (1924-25) Performed with the Ulysses Quartet playing the first parts 1. Adagio 2. Allegro molto FELIX MENDELSSOHN, (1809-1847 Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20, (1825) 1. Allegro moderato ma con fuoco (E-flat major) 2. Andante (C minor) 3. Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo (G minor) 4. Presto (E-flat major) The performance of The Ulysses and Emerson String Quartets has been made possible by a generous grant from The Arthur Loeb Foundation The summer season of 2021 honors the memory of our past President, MICHELLE R. -

A Shorter Finnegans Wake Ed. Anthony Burgess

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. A SHORTER FINNE GANS WAKE ]AMES]OYCE EDITED BY ANTHONY BURGESS NEW YORK THE VIKING PRESS "<) I \J I Foreword ASKED to name the twenty prose-works of the twentieth century most likely to survive into the twenty-first, many informed book-lovers would feel constrained to· include James Joyce's Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. I say "constrained" advisedly, because the choice of these two would rarely be as spontaneous as the choice of, say, Proust's masterpiece or a novel by D. H. Lawrence or Thomas Mann. Ulysses and Finnegans Wake are highly idiosyncratic and "difficult" books, admired more often than read, when read rarely read through to the end, when read through to the end not often fully, or even partially, under stood. This, of course, is especially t-rue of Finnegans Wake. And yet there are people who not only claim to understand a great deal of these books but affirm great love for them-love of an intensity more commonly accorded to Shakespeare or Jane Austen or Dickens. -

Finnegans Wake at 80 11–13 April 2019, Trinity College Dublin

Finnegans Wake at 80 11–13 April 2019, Trinity College Dublin Preliminary Programme (draft 2.0, 17/1/19) Wednesday 10 April 6:00: Welcome drinks (tba) Thursday 11 April 9:30–10:30: Plenary 1 (Neill Lecture Theatre, Long Room Hub) Chrissie Van Mierlo (Erewash Museum and Nottingham University, UK): Shaun at 80 (or 96): Verbivocovisualising Character in Finnegans Wake Chair: Sam Slote (Trinity College Dublin) 10.30–11.00: Coffee (Hoey Ideas Space, Long Room Hub) 11.00–12.30: Panel 1 (Neill Lecture Theatre, Long Room Hub) Talia Abu (Hebrew University of Jerusalem): The Evolution of Festy King’s Guilt Roland McHugh (independent scholar): Knickers in Finnegans Wake James Green (University of Manchester): ‘The Scholar and the Novelist’: Rehistoricizing the Middle Ages with Joyce and Joseph Bédier Wim Van Mierlo (Loughborough University): Revivals at the Wake: James Joyce’s Genealogical Art Chair: Wim Van Mierlo 12.30–1.30: Lunch 1.30–3.00: Panel 2 (Neill Lecture Theatre, Long Room Hub) Richard Barlow (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore): Introduction to a Finnegans Wake Digital Humanities Project Anne Marie D’Arcy (University of Leicester): ‘Postmantuam glasseries from the lapins and the grigs’: Biddy the Hen and the Exegetical Topos of aurum in stercore quaero Vincent Deane (independent scholar): Structure and Motif Revisited Robert Baines (University of Evansville): A Portrait of the Ondt as a Young Man Chair: Robert Baines 3.00–3.30: Coffee (Hoey Ideas Space, Long Room Hub) Waywords and Meansigns (Galbraith Seminar Room, Long Room Hub) An audio-visual installation with interactive elements, exploring Finnegans Wake as music. -

Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce's Finnegans Wake

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2020 Penman Contra Patriarch: Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce's Finnegans Wake Gabriel Beauregard Egset Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2020 Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Egset, Gabriel Beauregard, "Penman Contra Patriarch: Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce's Finnegans Wake" (2020). Senior Projects Fall 2020. 9. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2020/9 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects at Bard Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Projects Fall 2020 by an authorized administrator of Bard Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Penman Contra Patriarch Reimagining the Central Conflict of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Gabriel Egset Annandale-on-Hudson, New York December 2020 Egset 2 To my bestefar Ola Egset, we miss you dearly Egset 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 The Illustrated Penman…………………………………………………………………………………..................8 Spatial and Temporal Flesh: The Giant’s Chronotope………………………………………………….16 Cyclical Time: The Great Equalizer…………………………………………………………………………….21 The Gendered Wake Part I: Fertile Femininity…………………………………………………………...34 The Gendered Wake Part II: Sterile Masculinity…………………………………………………………39 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..54 Egset 4 Acknowledgements To my parents for their unconditional support: I love you both to the moon and back. -

A Dream Before the Dawn of the Digital Age? Finnegans Wake, Media, and Communications

A Dream Before the Dawn of the Digital Age? Finnegans Wake, Media, and Communications The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Shen, Emily. 2020. A Dream Before the Dawn of the Digital Age? Finnegans Wake, Media, and Communications. Bachelor's thesis, Harvard University Engineering and Applied Sciences. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367286 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A DREAM BEFORE THE DAWN OF THE DIGITAL AGE? FINNEGANS WAKE, MEDIA, AND COMMUNICATIONS by Emily Shen Presented to the Committee on Degrees in History and Literature and the Department of Computer Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Harvard College Cambridge, Massachusetts October 29, 2020 Word Count: 19,741 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 Writing Finnegans Wake ........................................................................................................... 4 The Emergence of Information Theory ................................................................................... 8 Finnegans Wake as Medium and Message ............................................................................ -

Music in Dubliners

Colby Quarterly Volume 28 Issue 1 March Article 4 March 1992 Music in Dubliners Robert Haas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 28, no.1, March 1992, p.19-33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Haas: Music in Dubliners Music in Dubliners by ROB ERTHAAS AM ES JOY e E was a musician before he ever became a writer. 1 He learned music as a child~ perfonned it for his family, friends~ and the public as a young Jman, and loved the arthis whole life long. The books ofHodgart and Worthington and of Bowen have traced how deeply and pervasively its role is felt throughout Joyce's fiction. 2 The great novels ofhis maturity, Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. contain more than a thousand musical episodes, incidents, and allusions. If Joyce's early fiction has less than this profusion~ it is perhaps simply because at the time he was not yet so bold an experimenter in literary style. The early works were~ nevertheless, produced by a man who was actively studying music, who was near his peak as a musical performer, and who still at times contemplated making music his life ~s career. When Joyce introduces music in his writing~ it is with the authority and significance ofan expert; and it is surely worth OUf while as readers to attend to it. In the present essay I would like to focus on the music inJoyce's early volume ofshort stories, Dubliners.