Writing 'That Animal Darkness': Galway Kinnell, Gary Snyder, James Merrill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Literary Firsts & Poetry Rare Books

ALEXANDER LITERARY FIRSTS & POETRY RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE TWENTY- SEVEN 2 Alexander Rare Books [email protected]/ (802) 476‐0838 ALEXANDER RARE BOOKS – LITERARY FIRSTS & POETRY Mark Alexander 234 Camp Street Barre, VT 05641 (802) 476-0838 [email protected] Catalogue Twenty–Seven: All items are US, CN or UK Hardcover First Editions & First Printings unless otherwise stated. All items guaranteed & are refundable for any reason within 30 days. Subject to prior sale. VT residents please add 6% sales tax. Checks, Money Orders, Paypal & most credit cards accepted. Net 30 days. Libraries & institutions billed according to need. Reciprocal terms offered to the trade. SHIPPING IS FREE IN THE US (generally Priority Mail) & CANADA, elsewhere $13 per shipment. Visit AlexanderRareBooks.com for cover scans and photos of most catalogued items. I encourage you to visit my website for the latest acquisitions. The best items usually appear on my website, then appear in my catalogues, before appearing elsewhere online. I am always interested in acquiring first editions, single copies or collections, and particularly modernist & contemporary poetry. Thank you in advance for perusing this catalogue. CATALOGUE TWENTY-SEVEN 1) Adam, Helen. THE BELLS OF DIS. West Branch, Iowa: Coffee House Press, 1985. Tall sewn illustrated wraps. Morning Coffee Chapbook: 12. One of 500 copies, numbered and signed by the poet and the artist Ann Mikolowski. A lovely book hand set and hand sewn. Bottom tips bumped, else fine. (10690) $20.00 2) Armantraut, Rae. CONCENTRATE. Green River, VT: Longhouse, 2007. Small (3 x 4 1/2 in.) accordion style chapbook attached to unprinted card covers, with wrap around band. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Galway Kinnell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Galway Kinnell - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Galway Kinnell(1 February 1927) Galway Kinnell is an American poet. He was Poet Laureate of Vermont from 1989 to 1993. An admitted follower of <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/walt- whitman/">Walt Whitman</a> , Kinnell rejects the idea of seeking fulfillment by escaping into the imaginary world. His best-loved and most anthologized poems are "St. Francis and the Sow" and "After Making Love We Hear Footsteps". <b>Biography</b> Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Kinnell said that as a youth he was turned on to poetry by <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/edgar-allan-poe/">Edgar Allan Poe</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/emily- dickinson/">Emily Dickinson</a>, drawn to both the musical appeal of their poetry and the idea that they led solitary lives. The allure of the language spoke to what he describes as the homogeneous feel of his hometown, Pawtucket, Rhode Island. He has also described himself as an introvert during his childhood. Kinnell studied at Princeton University, graduating in 1948 alongside friend and fellow poet <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/william-stanley- merwin/">W.S. Merwin</a>. He received his master of arts degree from the University of Rochester. He traveled extensively in Europe and the Middle East, and went to Paris on a Fulbright Fellowship. During the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States caught his attention. Upon returning to the US, he joined CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and worked on voter registration and workplace integration in Hammond, Louisiana. -

![Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova[3]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0056/celebrating-the-best-american-poetry-2018-at-villanova-3-450056.webp)

Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova[3]

Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova February 6, 2019 5:00 Connelly Center Cinema 6:15 (St. David’s Room) Reception and Book Signing Villanova University is honored to host the regional launch of the thirtieth anniversary edition of The Best American Poetry, guest edited by Dana Gioia, David Lehman, general editor. For three decades, the Best American Poetry has served as an annual occasion to recognize new work by American authors; inclusion is one of the great honors established and emerging poets may receive. The anthology was officially launched at New York University, in September 2018, but Villanova now brings together six of the anthology’s authors, along with David Lehman, for an evening of reading, discussion, and fellowship on our campus. David Lehman will chair the event, which will feature short readings from six poets: Maryann Corbett, Ernest Hilbert, Mary Jo Salter, Adrienne Su, Ryan Wilson, and Villanova’s own James Matthew Wilson. The public is warmly invited to this special evening to celebrate the achievement of contemporary letters and to join us for food and conversation afterwards. This event is sponsored by the Honors Program, the Villanova Center for Liberal Education, the Department of English, and the Department of Humanities. For more information, contact James Matthew Wilson, at [email protected] About the poets Maryann Corbett was born in Washington, DC, and grew up in northern Virginia. She earned a BA from the College of William and Mary and an MA and PhD from the University of Minnesota. She has published three books of poetry: Breath Control (2012); Credo for the Checkout Line in Winter (2013), which was a finalist for the Able Muse Book Prize; and Mid Evil (2014), the winner of the Richard Wilbur Award. -

Modern Poetry Seminar “Shifting Poetics: from High Modernism to Eco-Poetics to Black Lives Matter”

San José State University Department of English and Comparative Literature ENGLISH 211: Modern Poetry Seminar “Shifting Poetics: From High Modernism to Eco-Poetics to Black Lives Matter” Spring 2021 Instructor: Prof. Alan Soldofsky Office Location: FO 106 Telephone: 408-924-4432 Email: [email protected] Virtual Office Hours: M, W 3:00 – 4:30 PM, and Th p.m. by appointment Class Days/Time: Synchronous Zoom Meetings M 7:00 – 8:30 PM; Asynchronous on Canvas (24/7) Classroom: Zoom Credit Units: 4 Credits Course Description This seminar is designed to engage students in an immersive study of salient themes and innovations in selected poets from the 20th and 21st centuries. The curriculum will include practice in close reading/explication of selected poems. The course will be taught in a partially synchronous distance learning mode, using SJSU’s Canvas and Zoom platforms, with weekly Monday Zoom class meetings, 7:00 – 8:15 p.m. The course may be taken two times for credit (toward an MA or MFA degree). Thematic Focus Shifting Cultural Politics and Poetics from High Modernism to Eco-Poetics to Black Lives Matter (1909 – 2021) The emphasis during the semester will be on the evolving poetics and associated cultural politics as viewed through various aesthetic movements in poetry from the high modernist period to the present. During the semester the curriculum will include reading one or more poems (online) by the following poets: W.B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Marianne Moore, Robinson Jeffers, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, H. -

Culture and Humor in Postwar American Poetry

Palacký University, Olomouc Culture and Humor in Postwar American Poetry Jiří Flajšar Olomouc 2014 Reviewers: doc. Mgr. Jakub Guziur, Ph.D. Mgr. Vladimíra Fonfárová “The research and publication of this book was in the years 2012–2014 financed by the Faculty of Arts, Palacký University, Olomouc from the Fund for the Research Advancement.” All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, now known or hereafter invented, without written permission by the copyright holder. © Jiří Flajšar, 2014 © Palacký University, Olomouc, 2014 First Edition ISBN 978-80-244-4158-0 This book is dedicated to my family. Contents Introduction 7 Crisis or Not: On the Situation of American Poetry and Its Audience 17 Humor as a Method in Postwar American Culture Poetry 33 Allen Ginsberg: Odyssey in the American Supermarket 43 Kenneth Koch: The Poet as Serious Comic 63 “Reality U.S.A.”: The Poetry of Mark Halliday 81 R.S. Gwynn: The New Formalist Shops at the Mall 107 Campbell McGrath: The Poet as a Representative Product of American Culture 127 Tony Hoagland: The Poetry of Ironic Self-Deprecation 185 Billy Collins: The Genteel Commentator 207 Culture, Identity, and Humor in Contemporary Chinese-American Poetry 215 Bibliography 227 Index 247 Introduction The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem. —Walt Whitman Something we were withholding made us weak Until we found out that it was ourselves We were withholding from our land of living —Robert Frost What counted was mythology of the self, Blotched out beyond unblotching. -

Galway Kinnell: Adamic Poet and Deep Imagist. Leo Luke Marcello Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 Galway Kinnell: Adamic Poet and Deep Imagist. Leo Luke Marcello Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Marcello, Leo Luke, "Galway Kinnell: Adamic Poet and Deep Imagist." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2930. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2930 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Reading by David Lehman

FOR IMMEDIATE PRESS RELEASE 4-5-17 EVENTS: Poets of National Stature Reading Series presents: Leading poet David Lehman o Reading by David Lehman, author of Poems in the Manner Of… at Writer’s Block o Dylan, the Nobel, & the Jewish American Songbook, lecture & discussion led by David Lehman. WHO: David Lehman is one of America’s leading poets using humor and everyday language to bring us great insight into the most powerful thoughts and feelings of life. He wrote an article recently regarding Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize for the Wall Street Journal and was quoted prominently on the topic in the Washington Post. David Lehman’s books include Yeshiva Boys, A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters American Songs, and most recently, Poems in the Manner of.... He edits the Best American Poetry series the Oxford Book ofAmerican Poetry. As series editor, he has earned high acclaim for his pivotal role in garnering contemporary American poetry a larger audience. One of the foremost editors, literary critics, and anthologists of contemporary American literature, David Lehman is also one of our most accomplished poets. WHEN: Reading by David Lehman: Saturday, May 20, 7:00-8:30 p.m., Writer’s Block 1020 Fremont St #100, Las Vegas, NV 89101. Dylan, the Nobel, & the Jewish American Songbook – Lecture & Discussion by David Lehman: Sunday, May 21, 3 - 4:30 p.m. Congregation Ner Tamid, Beit Tefillah (Room) 55 N Valle Verde Dr, Henderson, NV 89074. COST: Both events are free and open to the public. CONTACT: Bruce Isaacson, CC Poet Laureate 702-205-7100 or [email protected] Angela M. -

UC Creative Writing Newsletter

Spring 2017 DIRECTOR’S NOTE BY LEAH STEWART CREATIVE This is my last note as director, as Rebecca Lindenberg will take over that position in the fall. We’re delighted that Rebecca, who joined us two years ago as a visiting assistant WRITING professor in poetry, will also become a permanent member of the faculty. Michael Griffith will be taking a well-deserved sabbatical after his five years as Director of Graduate Studies, CONTENTS and as of the fall I'll be department head. I've enjoyed DEPARTMENT NEWS directing the program, particularly curricular development; FACULTY NEWS we've just changed our Creative Writing major to a multi- ALUMNI NEWS genre approach, after years of requiring students to select a STUDENT NEWS genre. This has allowed us to create innovative classes like INCOMING STUDENTS Creative Writing and Research, Hybrid Forms, Comic Poetry and Prose, and so on, which we're looking forward to teaching—and inviting graduate students to teach—next year and beyond. In other news, it's been a pleasure to welcome Lisa Ampleman, a poet who graduated from our program in 2013, back to the department in her new capacity as managing editor of The Cincinnati Review. Nicola Mason's new venture, Acre Books, released its first publication, A Very Angry Baby, an anthology that includes work by Brock Clarke, Andrew Hudgins, and Julianna Baggott. Back in February, Cincinnati www.artsci.uc.edu/creativewriting Magazine wrote an article about our program, which you can read here. If you haven't yet taken a look at the Elliston Project—an audio archive of more than 700 recorded readings and lectures given at UC since 1951—you can do so here. -

Two Journeys

PHILIP LEVINE TWO JOURNEYS Is. what follows a fiction by Balzac? It would seem unlikely, for there is no one standing out in the dark on a rain-swept night as a carriage pulled by six gray horses splashes down the Boulevard Raspail on the way to the apartment of that singularly beautiful woman, Madame La Pointe, although it does involve a beautiful and singularly gifted woman. Is it a fiction at all? That is a harder question to deal with. If Norman Mailer had written it and its central character were a novelist living in Brooklyn, the author of an astOnishingly successful first book called The Naked and the Dead, a man deeply immersed in an ongoing depiction of the CIA, he would describe it as a fiction, and he would most likely name the central character Norman Mailer. One of my central characters is named Philip Levine, he is a poet from Detroit, he lives mainly in Fresno, California, where he has an awful job teaching too many courses in freshman comp at the local col lege, and on this particular summer day he is traveling with two fellow poets by train to give a reading almost no one will attend. It is twenty years ago, he is in his fiftieth year, as I was then, and though I cannot call it a fiction, I will begin now to fictionalize this tale. I will say the local railway has a reputation for first-rate service, they are never more than a few minutes late even in the worst weather, and on this day the weather is a delight: blue sky with a few puffy clouds overhead as the poets head for the provincial town where their reading, though almost entirely unadvertised, will become the event of that summer's cultural history, a history that wiII never be written except for the present effort, which The Hopwood Lecture, 1997 393 394 MICHIGAN QUARTERLY REVIEW since it may be a fiction may not be a history at all. -

The Best American Poetry 2009 Series Editor David Lehman 1St Edition Download Free

THE BEST AMERICAN POETRY 2009 SERIES EDITOR DAVID LEHMAN 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE David Wagoner | 9780743299770 | | | | | The Best American Poetry 2009 : Series Editor David Lehman Views Read Edit View history. The list doesn't have to make any sense at all. All right, I'll say weird stuff about the fifty states, just meaningless stuff, and string it all togetherthinks Bibbins's clogged brain one fall morning at the New School. Please enter a valid email address. The editor groups poems of particular styles together, and they seemed to progress from more traditional to those that have a more modern flavor. Email address. Known for his marvelous narrative skill and humane wit, David Wagoner is one of the few poets of his generation to win the universal admiration of his peers. Like, what are the things I would do if I met Moses in a laundry room in a twenty-fifth century spaceship? He has been a contributing editor at The American Scholar[35] sincewhere he acts as quiz master for the weekly column Next Line, Pleasea public poetry-writing contest, in addition to writing various articles. A smile of complicity. For years, the Best American Poetry series, edited by David Lehman, has been on a downward slope using slope in the most generous sense of the word. Lehman, David December 4, And poets in America today are defining nothing as much as they are defining poetry itself. About This Item. Join HuffPost. See our disclaimer. This is gibberish pretending to be poetry. To ensure we are able to help you as best we can, please include your reference number:. -

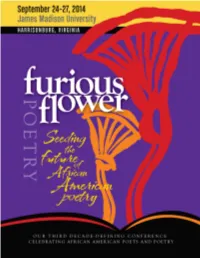

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa.