A Mixed-Methods Study of Okinawan Public Perceptions of the US Military

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peace in Vietnam! Beheiren: Transnational Activism and Gi Movement in Postwar Japan 1965-1974

PEACE IN VIETNAM! BEHEIREN: TRANSNATIONAL ACTIVISM AND GI MOVEMENT IN POSTWAR JAPAN 1965-1974 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE AUGUST 2018 By Noriko Shiratori Dissertation Committee: Ehito Kimura, Chairperson James Dator Manfred Steger Maya Soetoro-Ng Patricia Steinhoff Keywords: Beheiren, transnational activism, anti-Vietnam War movement, deserter, GI movement, postwar Japan DEDICATION To my late father, Yasuo Shiratori Born and raised in Nihonbashi, the heart of Tokyo, I have unforgettable scenes that are deeply branded in my heart. In every alley of Ueno station, one of the main train stations in Tokyo, there were always groups of former war prisoners held in Siberia, still wearing their tattered uniforms and playing accordion, chanting, and panhandling. Many of them had lost their limbs and eyes and made a horrifying, yet curious, spectacle. As a little child, I could not help but ask my father “Who are they?” That was the beginning of a long dialogue about war between the two of us. That image has remained deep in my heart up to this day with the sorrowful sound of accordions. My father had just started work at an electrical laboratory at the University of Tokyo when he found he had been drafted into the imperial military and would be sent to China to work on electrical communications. He was 21 years old. His most trusted professor held a secret meeting in the basement of the university with the newest crop of drafted young men and told them, “Japan is engaging in an impossible war that we will never win. -

Japan Has Still Yet to Recognize Ryukyu/Okinawan Peoples

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan Prepared for 128th Session, Geneva, 2 March - 27 March, 2020 Submitted by Cultural Survival Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 [email protected] www.culturalsurvival.org International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan I. Reporting Organization Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC since 2005. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly, and on its website: www.cs.org. II. Introduction The nation of Japan has made some significant strides in addressing historical issues of marginalization and discrimination against the Ainu Peoples. However, Japan has not made the same effort to address such issues regarding the Ryukyu Peoples. Both Peoples have been subject to historical injustices such as suppression of cultural practices and language, removal from land, and discrimination. Today, Ainu individuals continue to suffer greater rates of discrimination, poverty and lower rates of academic success compared to non-Ainu Japanese citizens. Furthermore, the dialogue between the government of Japan and the Ainu Peoples continues to be lacking. The Ryukyu Peoples continue to not be recognized as Indigenous by the Japanese government and face the nonconsensual use of their traditional lands by the United States military. -

Uhm Phd 9506222 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM! films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent UJWD the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adverselyaffect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-band comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms tnternauonat A Bell & Howell tntorrnatron Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800:521·0600 Order Number 9506222 The linguistic and psycholinguistic nature of kanji: Do kanji represent and trigger only meanings? Matsunaga, Sachiko, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 Copyright @1994 by Matsunaga, Sachiko. -

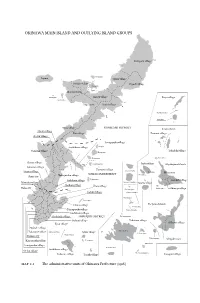

Okinawa Main Island and Outlying Island Groups

OKINAWA MAIN ISLAND AND OUTLYING ISLAND GROUPS Kunigami village Kourijima Iejima Ōgimi village Nakijin village Higashi village Yagajijima Ōjima Motobu town Minnajima Haneji village Iheya village Sesokojima Nago town Kushi village Gushikawajima Izenajima Onna village KUNIGAMI DISTRICT Kerama Islands Misato village Kin village Zamami village Goeku village Yonagusuku village Gushikawa village Ikeijima Yomitan village Miyagijima Tokashiki village Henzajima Ikemajima Chatan village Hamahigajima Irabu village Miyakojima Islands Ginowan village Katsuren village Kita Daitōjima Urasoe village Irabujima Hirara town NAKAGAMI DISTRICT Simojijima Shuri city Nakagusuku village Nishihara village Tsukenjima Gusukube village Mawashi village Minami Daitōjima Tarama village Haebaru village Ōzato village Kurimajima Naha city Oki Daitōjima Shimoji village Sashiki village Okinotorishima Uozurijima Kudakajima Chinen village Yaeyama Islands Kubajima Tamagusuku village Tono shirojima Gushikami village Kochinda village SHIMAJIRI DISTRICT Hatomamajima Mabuni village Taketomi village Kyan village Oōhama village Makabe village Iriomotejima Kumetorishima Takamine village Aguni village Kohamajima Kume Island Itoman city Taketomijima Ishigaki town Kanegusuku village Torishima Kuroshima Tomigusuku village Haterumajima Gushikawa village Oroku village Aragusukujima Nakazato village Tonaki village Yonaguni village Map 2.1 The administrative units of Okinawa Prefecture (1916) <UN> Chapter 2 The Okinawan War and the Comfort Stations: An Overview (1944–45) The sudden expansion -

Establishing Okinawan Heritage Language Education

Establishing Okinawan heritage language education ESTABLISHING OKINAWAN HERITAGE LANGUAGE EDUCATION Patrick HEINRICH (University of Duisburg-Essen) ABSTRACT In spite of Okinawan language endangerment, heritage language educa- tion for Okinawan has still to be established as a planned and purposeful endeavour. The present paper discusses the prerequisites and objectives of Okinawan Heritage Language (OHL) education.1 It examines language attitudes towards Okinawan, discusses possibilities and constraints un- derlying its curriculum design, and suggests research which is necessary for successfully establishing OHL education. The following results are presented. Language attitudes reveal broad support for establishing Ok- inawan heritage language education. A curriculum for OHL must consid- er the constraints arising from the present language situation, as well as language attitudes towards Okinawan. Research necessary for the estab- lishment of OHL can largely draw from existing approaches to foreign language education. The paper argues that establishment of OHL educa- tion should start with research and the creation of emancipative ideas on what Okinawan ought to be in the future – in particular which societal functions it ought to fulfil. A curriculum for OHL could be established by following the user profiles and levels of linguistic proficiency of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. 1 This paper specifically treats the language of Okinawa Island only. Other languages of the Ryukyuan language family such as the languages of Amami, Miyako, Yaeyama and Yonaguni are not considered here. The present paper draws on research conducted in 2005 in Okinawa. Research was supported by a Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science fellowship which is gratefully acknowledged here. -

Growing Democracy in Japan: the Parliamentary Cabinet System Since 1868

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky University of Kentucky UKnowledge Asian Studies Race, Ethnicity, and Post-Colonial Studies 5-15-2014 Growing Democracy in Japan: The Parliamentary Cabinet System since 1868 Brian Woodall Georgia Institute of Technology Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Woodall, Brian, "Growing Democracy in Japan: The Parliamentary Cabinet System since 1868" (2014). Asian Studies. 4. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_asian_studies/4 Growing Democracy in Japan Growing Democracy in Japan The Parliamentary Cabinet System since 1868 Brian Woodall Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results. Copyright © 2014 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Woodall, Brian. -

United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council Chairs: Natalia Constantine Katie Hamlin Committee Topics: Topic 1: Nuclear Weapons in North Korea Topic 2: Syria Cessation of Hostilities Topic 3: Senkaku Islands Dispute 0 Chair Biographies Hello delegates! My name is Natalia Constantine and I’m in my senior year. I have been in MUN since 8th grade and this is my second time chairing, but my first time participating in Security Council. Besides MUN, I am on the tennis team, masque, and the school’s mathletics team. I am hoping for a fun and educational conference with resolutions passed, please do not hesitate in contacting me at [email protected] if you have any questions. See you all December 10th! Good day delegates! I am Katherine Hamlin, and I am a Junior this year at New Hartford High School. I have participated in MUN since I was in 8th grade and this will be my first time serving as a chair. Outside of MUN, I am also a distance swimmer for our school’s Varsity Swim team, a member of our French and Latin clubs, and a member of our Students for Justice and Equality club. I am greatly looking forward to serving as a chair on Security Council, and I hope that it will be an interesting and productive committee. If you have any questions, please contact me at [email protected] See you in December! Special Committee Notes Our simulation of the Security Council will be run Harvard Style. This means that there will be NO pre-written resolutions allowed in committee. -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

Effects of Constructing a New Airport on Ishigaki Island

Island Sustainability II 181 Effects of constructing a new airport on Ishigaki Island Y. Maeno1, H. Gotoh1, M. Takezawa1 & T. Satoh2 1Nihon University, Japan 2Nihon Harbor Consultants Ltd., Japan Abstract Okinawa Prefecture marked the 40th anniversary of its reversion to Japanese sovereignty from US control in 2012. Such isolated islands are almost under the environment separated by the mainland and the sea, so that they have the economic differences from the mainland and some policies for being active isolated islands are taken. It is necessary to promote economical measures in order to increase the prosperity of isolated islands through initiatives involving tourism, fisheries, manufacturing, etc. In this study, Ishigaki Island was considered as an example of such an isolated island. Ishigaki Island is located to the west of the main islands of Okinawa and the second-largest island of the Yaeyama Island group. Ishigaki Island falls under the jurisdiction of Okinawa Prefecture, Japan’s southernmost prefecture, which is situated approximately half-way between Kyushu and Taiwan. Both islands belong to the Ryukyu Archipelago, which consists of more than 100 islands extending over an area of 1,000 km from Kyushu (the southwesternmost of Japan’s four main islands) to Taiwan in the south. Located between China and mainland Japan, Ishigaki Island has been culturally influenced by both countries. Much of the island and the surrounding ocean are protected as part of Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park. Ishigaki Airport, built in 1943, is the largest airport in the Yaeyama Island group. The runway and air security facilities were improved in accordance with passenger demand for larger aircraft, and the airport became a tentative jet airport in May 1979. -

Genetic Lineage of the Amami Islanders Inferred from Classical Genetic Markers

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Genetic lineage of the Amami islanders inferred from classical genetic markers Yuri Nishikawa and Takafumi Ishida Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan Correspondence: Yuri Nishikawa, Department of Biological Sciences, Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, Hongo 7-3-1, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan. E-mail address: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440379; this version posted April 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The peopling of mainland Japan and Okinawa has been gradually unveiled in the recent years, but previous anthropological studies dealing people in the Amami islands, located between mainland Japan and Okinawa, were less informative because of the lack of genetic data. In this study, we collected DNAs from 104 subjects in two of the Amami islands, Amami-Oshima island and Kikai island, and analyzed the D-loop region of mtDNA, four Y-STRs and four autosomal nonsynonymous SNPs to clarify the genetic structure of the Amami islanders comparing with peoples in Okinawa, mainland Japan and other regions in East Asia. -

Deconstructing Japan's Claim of Sovereignty Over the Diaoyu

Volume 10 | Issue 53 | Number 1 | Article ID 3877 | Dec 30, 2012 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Deconstructing Japan’s Claim of Sovereignty over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands 釣魚/尖閣に対する日本の統治権を脱構築 する Ivy Lee, Fang Ming “The near universal conviction in Japan with has shown effective control to be determinative which the islands today are declared an in a number of its rulings, a close scrutiny of ’integral part of Japan’s territory‘ is remarkable Japan’s effective possession/control reveals it to for its disingenuousness. These are islands have little resemblance to the effective unknown in Japan till the late 19th century possession/control in other adjudicated cases. (when they were identified from British naval As international law on territorial disputes, in references), not declared Japanese till 1895, theory and in practice, does not provide a not named till 1900, and that name not sound basis for its claim of sovereignty over the revealed publicly until 1950." GavanDiaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Japan will hopefully McCormack (2011)1 set aside its putative legal rights and, for the sake of peace and security in the region, start Abstract working with China toward a negotiated and mutually acceptable settlement. In this recent flare-up of the island dispute after Japan “purchased” three of theKeywords Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Japan reiterates its position that “the Senkaku Islands are an Diaoyu Dao, Diaoyutai, Senkakus, territorial inherent part of the territory of Japan, in light conflict, sovereignty, of historical facts and based upon international law.” This article evaluates Japan’s claims as I Introduction expressed in the “Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands”A cluster of five uninhabited islets and three published on the website of the Ministry of rocky outcroppings lies on the edge of the East Foreign Affairs, Japan. -

Restoration of the Native Species to Amami Oshima Island

alien species in Amami Oshima Island In addition to the Small Indian mongoose, many other alien species (e.g., feral cats, feral goats, black rats and the Lanceleaf tickseed) have become established on Amami Oshima. Please be sure never to leave behind alien species in the wild nor let them escape. Feral cat Feral goat Black rat Lanceleaf tickseed ● Alien species of Amami Islands HP http://kyushu.env.go.jp/naha/wildlife/data/130902aa.pdf We ask for your cooperation in The mongoose eradication project activity of Amami Mongoose Busters in Amami Oshima The Amami Mongoose Busters, which was formed in 2005, has continued its efforts to eradicate mongooses with the support of people in the island and researchers. We ask for your continued onservation of a precious understanding and support of the mongoose control project as C well as the Amami Mongoose Busters. ecosystem in ■ Amami Mongoose Busters Blog http://amb.amamin.jp/ ■ Amami Mongoose Busters Facebook Amami Oshima Island https://www.facebook.com/amamimongoosebusters March 2014 Amami Wildlife Conservation Center, Published by: Ministry of the Environment, Japan Naha Nature Conservation Office, 551 Koshinohata, Ongachi, Yamato-son, Oshima-gun, Ministry of the Environment, Japan Kagoshima 894-3104 TEL:+81-997-55-8620 Okinawa Tsukansha Building 4F, 5-21 Yamashita-cho, Japan Wildlife Research Center, Naha-shi, Okinawa 900-0027 Amami Ooshima Division (Amami Mongoose Busters) 1385-2 Naze, Uragami,Amami-City, Kagoshima 894-0008 TEL:+81-997-58-4013 Edited by : Japan Wildlife Research Center FOR ALL THE LIFE ON EARTH Design : artpost inc. Photos : Mamoru Tsuneda, Teruho Abe, Yoshihito Goto, Kazuki Yamamuro, Biodiversity Ryuta Yoshihara, Japan Wildlife Research Center Animals and plants Habu snake Protobothrops flavoviridis This poisonous snake is found on Amami Oshima, Tokunoshima, Okinawa in Amami Oshima Island Island, and other several neighboring small islands.