The Silent Emergency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction: Regional Report

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES/ETHNIC MINORITIES AND POVERTY REDUCTION REGIONAL REPORT Roger Plant Environment and Social Safeguard Division Regional and Sustainable Development Department Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines June 2002 © Asian Development Bank 2002 All rights reserved Published June 2002 The views and interpretations in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asian Development Bank. ISBN No. 971-561-438-8 Publication Stock No. 030702 Published by the Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980, Manila, Philippines FOREWORD his publication was prepared in conjunction with an Asian Development Bank (ADB) regional technical assistance (RETA) project on Capacity Building for Indigenous Peoples/ T Ethnic Minority Issues and Poverty Reduction (RETA 5953), covering four developing member countries (DMCs) in the region, namely, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Viet Nam. The project is aimed at strengthening national capacities to combat poverty and at improving the quality of ADB’s interventions as they affect indigenous peoples. The project was coordinated and supervised by Dr. Indira Simbolon, Social Development Specialist and Focal Point for Indigenous Peoples, ADB. The project was undertaken by a team headed by the author, Mr. Roger Plant, and composed of consultants from the four participating DMCs. Provincial and national workshops, as well as extensive fieldwork and consultations with high-level government representatives, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), and indigenous peoples themselves, provided the basis for poverty assessment as well as an examination of the law and policy framework and other issues relating to indigenous peoples. Country reports containing the principal findings of the project were presented at a regional workshop held in Manila on 25–26 October 2001, which was attended by representatives from the four participating DMCs, NGOs, ADB, and other finance institutions. -

Mon-Khmer Studies Volume 41

Mon-Khmer Studies VOLUME 42 The journal of Austroasiatic languages and cultures Established 1964 Copyright for these papers vested in the authors Released under Creative Commons Attribution License Volume 42 Editors: Paul Sidwell Brian Migliazza ISSN: 0147-5207 Website: http://mksjournal.org Published in 2013 by: Mahidol University (Thailand) SIL International (USA) Contents Papers (Peer reviewed) K. S. NAGARAJA, Paul SIDWELL, Simon GREENHILL A Lexicostatistical Study of the Khasian Languages: Khasi, Pnar, Lyngngam, and War 1-11 Michelle MILLER A Description of Kmhmu’ Lao Script-Based Orthography 12-25 Elizabeth HALL A phonological description of Muak Sa-aak 26-39 YANIN Sawanakunanon Segment timing in certain Austroasiatic languages: implications for typological classification 40-53 Narinthorn Sombatnan BEHR A comparison between the vowel systems and the acoustic characteristics of vowels in Thai Mon and BurmeseMon: a tendency towards different language types 54-80 P. K. CHOUDHARY Tense, Aspect and Modals in Ho 81-88 NGUYỄN Anh-Thư T. and John C. L. INGRAM Perception of prominence patterns in Vietnamese disyllabic words 89-101 Peter NORQUEST A revised inventory of Proto Austronesian consonants: Kra-Dai and Austroasiatic Evidence 102-126 Charles Thomas TEBOW II and Sigrid LEW A phonological description of Western Bru, Sakon Nakhorn variety, Thailand 127-139 Notes, Reviews, Data-Papers Jonathan SCHMUTZ The Ta’oi Language and People i-xiii Darren C. GORDON A selective Palaungic linguistic bibliography xiv-xxxiii Nathaniel CHEESEMAN, Jennifer -

Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: Phd

Access to Electronic Thesis Author: Lonán Ó Briain Thesis title: Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: PhD This electronic thesis is protected by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No reproduction is permitted without consent of the author. It is also protected by the Creative Commons Licence allowing Attributions-Non-commercial-No derivatives. If this electronic thesis has been edited by the author it will be indicated as such on the title page and in the text. Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain May 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music University of Sheffield © 2012 Lonán Ó Briain All Rights Reserved Abstract Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain While previous studies of Hmong music in Vietnam have focused solely on traditional music, this thesis aims to counteract those limited representations through an examination of multiple forms of music used by the Vietnamese-Hmong. My research shows that in contemporary Vietnam, the lives and musical activities of the Hmong are constantly changing, and their musical traditions are thoroughly integrated with and impacted by modernity. Presentational performances and high fidelity recordings are becoming more prominent in this cultural sphere, increasing numbers are turning to predominantly foreign- produced Hmong popular music, and elements of Hmong traditional music have been appropriated and reinvented as part of Vietnam’s national musical heritage and tourism industry. Depending on the context, these musics can be used to either support the political ideologies of the Party or enable individuals to resist them. -

Conference Bulletin

CONFERENCE BULLETIN International Conference on Language Development, Language Revitalization and Multilingual Education in Ethnolinguistic Communities 1-3 July, 2008 Bangkok, Thailand -1- CONFERENCE BULLETIN International Conference on Language Development, Language Revitalization and Multilingual Education in Ethnolinguistic Communities 1-3 July 2008 Bangkok, Thailand Printed by: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development Mahidol University ISBN: 978-974-8349-47-3 Printed at: Threelada Limited Partnership, Bangkok Tel. (662)462 0303 -2- PREFACE Since the 1st International Conference on Language Development, Language Revitalization and Multilingual Education in 2003,1 increasing numbers of ethnolinguistic communities, NGOs, universities and governments in Asia and the Pacific have expressed interest in and /or begun implementing mother tongue-based multilingual education (MT-based MLE) programs for children and adults who do not speak or understand the language used in mainstream education. That trend now seems to be growing in Africa as well. Also during that time, there as been an increase in the number of efforts in many parts of the world to document, revitalize and sustain the heritage languages and cultures of non-dominant language communities through language development (LD) and language revitalization (LR) programs. In spite of these efforts, the purposes and benefits of language development, language revitalization and multilingual education are still not widely understood or accepted. Many LD, LR and MT-based MLE efforts remain quite weak and do not build on what has been learned through research and practice around the world. Clearly, more awareness-raising and advocacy are still needed. Also needed is more information about what works and what does not work in planning, implementing and sustaining strong LD, LR and MT-based MLE programs. -

Photo by Chan Sokheng.

(Photo by Chan Sokheng.) Livelihoods in the Srepok River Basin in Cambodia: A Baseline Survey Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ii Acknowledgements iii Map of the Srepok River Basin iv Map of the Major Rivers of Cambodia v Executive Summary vi 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Methodology 1 1.2 Scope and limitations 3 2. The Srepok River and Tributaries 4 3. Protected Areas 7 4. Settlement and Ethnicity 8 5. Land and the Concept of Village 12 6. Water Regime 14 7. Transport 17 8. Livelihoods 19 8.1 Lowland (wet) rice cultivation 19 8.2 Other cultivation of crops 22 8.3 Animal raising 25 8.4 Fishing 27 8.5 Wildlife collection 42 8.6 Collection of forest products 43 8.7 Mining 47 8.8 Tourism 49 8.9 Labor 49 8.10 Water supply 50 8.11 Health 51 9. Implications for Development Practitioners and Directions for Future Research 52 Annex 1. Survey Villages and Ethnicity 55 Annex 2. Data Collection Guides Used During Fieldwork 56 Annex 3. Maximum Sizes (kg) of Selected Fish Species Encountered in Past Two Years 70 References 71 i Livelihoods in the Srepok River Basin in Cambodia: A Baseline Survey List of Figures and Tables Figure 1: Map of the Srepok basin in Cambodia and target villages 2 Figure 2: Rapids on the upper Srepok 4 Figure 3: Water levels in the Srepok River 4 Figure 4: The Srepok River, main tributaries, and deep-water pools on the Srepok 17 Figure 5: Protected areas in the Srepok River basin 7 Figure 6: Ethnic groups in the Srepok River basin in Cambodia 11 Figure 7: Annual spirit ceremony in Chi Klap 12 Figure 8: Trends in flood levels 14 Figure 9: Existing and proposed hydropower dam sites within the basin 15 Figure 10: Road construction, Pu Chry Commune (Pech Roda District, Mondulkiri) 17 Figure 11: Dikes on tributaries of the Srepok 21 Figure 12. -

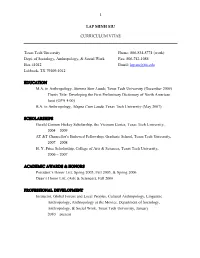

LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806

1 LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806-834-8774 (work) Dept. of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work Fax: 806-742-1088 Box 41012 Email: [email protected] Lubbock, TX 79409-1012 EDUCATION M.A. in Anthropology, Summa Sum Laude, Texas Tech University (December 2009) Thesis Title: Developing the First Preliminary Dictionary of North American Jarai (GPA 4.00) B.A. in Anthropology, Magna Cum Laude, Texas Tech University (May 2007) SCHOLARSHIPS Gerald Cannon Hickey Scholarship, the Vietnam Center, Texas Tech University, 2004 – 2009 AT &T Chancellor’s Endowed Fellowship, Graduate School, Texas Tech University, 2007 – 2008 H. Y. Price Scholarship, College of Arts & Sciences, Texas Tech University, 2006 – 2007 ACADEMIC AWARDS & HONORS President’s Honor List, Spring 2005, Fall 2005, & Spring 2006 Dean’s Honor List, (Arts & Sciences), Fall 2006 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Instructor, Global Forces and Local Peoples, Cultural Anthropology, Linguistic Anthropology, Anthropology at the Movies. Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January 2010 – present 2 Research Assistant/Language Consultant (Jarai). Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, June 2007 – December 2009 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. Jarai-Rhade Language Fonts Consultant. Linguist’s Software, Inc., July – September 2008 Assisted with the development and implementation of fonts for the Jarai and Rhade languages (www.linguistsoftware.com). Student/Language Consultant (Jarai). The Vietnam Center and Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January – May 2007 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. -

Indigenous Music Mediation with Urban Khmer: Tampuan Adaptation and Survival

Indigenous Music Mediation with Urban Khmer: Tampuan Adaptation and Survival Todd Saurman+ (U.S.A.) Abstract This paper describes some lowland/highland Khmer points of interconnection for indigenous Tampuan communities from the highland Northeast, Cambodia. Tam- puan community musicians respond constructively to a Siem Reap tourist cultural show that depicts their indigenous ethnolinguistic group. Tampuan musicians make trips to the urban center of Phnom Penh to represent themselves in a CD recording, a concert, and a TV program. I contend that some community members are expressing strong cultural values as they mediate with the national and urban culture in spite of a history of Khmerization efforts by lowland Khmer. A strong value of mediation reinforces highland desires to communicate with outsiders perceived as having great effect on highland everyday life. Meanwhile some urban Khmer who may mourn the loss of Khmer traditional culture and support its revival have demonstrated interest in the traditional cultures of Khmer highland communities as they possibly empathize with others perceived to be experiencing levels of alienation and marginalization similar to their own. Keywords: Cambodia, Indigenous, Music, Revitalization, Cultural Change, Mediation + Dr. Todd Saurman, Asia Area Coordinator for Ethnomusicology, SIL International. email: [email protected]. Indigenous Music Mediation with Urban Khmer – Tampuan Adaptation and Survival | 27 Introduction The Cambodian highland indigenous people are quite possibly the least likely group to come to mind when considering urban issues. Even though migration to Cambodia’s largest city, Phnom Penh, is rare, they do connect in some surprising ways. As Anna Tsing demonstrates in “In the Realm of the Diamond Queen”, so called marginalized indigenous groups, their marginalized subgroups (women in Tsing’s study), and apparent marginalized individuals (a “crazy” woman/ shaman) can be keenly aware of issues related to the national and international worlds of urbanites (Tsing, 1993). -

Behind the Lens

BEHIND THE LENS Synopsis On the banks of the Mekong, where access to education is a daily struggle, six children of different ages dream of a better future. Like the pieces of a puzzle, the paths taken by Prin, Myu Lat Awng, Phout, Pagna, Thookolo and Juliet fit together to tell the amazing story of WHEN I GROW UP. WHEN I GROW UP is first and foremost a story of a coming together. A coming together of a charity, Children of the Mekong, which has been helping to educate disadvantaged children since 1958; with a committed audio-visual production company, Aloest; with a film director, Jill Coulon, in love with Asia and with stories with a strong human interest; with a pair of world-famous musicians, Yaël Naïm and David Donatien. These multiple talents have collaborated to produce a wonderful piece of cinema designed to inform as many people as possible of the plight of these children and of the benefits of getting an education. Find out more at www.childrenofthemekong.org Credits: A film by Jill Coulon Produced by François-Hugues de Vaumas and Xavier de Lauzanne Director: Jill Coulon Assistant Director: Antoine Besson Editing: Daniel Darmon Audio mixing: Eric Rey Colour grading: Jean-Maxime Besset Music : Yaël Naïm and David Donatien Subtitles: Raphaële Sambardier Translation: Garvin Lambert Graphic design: Dare Pixel Executive Production Company: Aloest films Associate Production Company: Children of the Mekong INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR Jill Coulon A professional film director with a passion for all things Asia, Jill Coulon put her talent at the disposal of the six narrators of WHEN I GROW UP so they could tell their stories to an international audience. -

Providing Quality Education for Children with Disabilities in Developing Countries: Possibilities and Limitations of Inclusive Education in Cambodia

Providing Quality Education for Children with Disabilities in Developing Countries: Possibilities and Limitations of Inclusive Education in Cambodia 発展途上国における障害児教育の提供 -カンボジアにおけるインクルーシブ教育の可能性と限界― DIANA KARTIKA Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Studies Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies Waseda University © 2017 Diana Kartika All Rights Reserved SUMMARY Located within the two fields of disability studies and education development, this empirical study sheds light on the forces facilitating and hindering the education and development of children with disabilities (CwDs) in a developing country context and seeks to provide a universal framework for examining the complexities of inclusive education. Based on Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological systems theory, this study analyses the influence of actors and processes in Cambodia at the bio-, micro-, meso-, exo-, and chrono-levels, on access and quality of education for CwDs. It then identifies ecological niches of possibilities that capitalise on the strengths of local communities, for effective and sustainable intervention in Cambodia. This study was conducted in Battambang, Kampot, Kandal, Phnom Penh, and Ratanakiri in February and July 2015. A total of 88 interviews were conducted with 119 respondents: 50 individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with parents at their homes, 19 focus group interviews were conducted with 50 teachers, and 19 individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with school directors in schools. Participatory observations were also carried out at 50 homes, 6 classes, and 19 schools. Secondary empirical quantitative data and findings from Kuroda, Kartika, and Kitamura (2017) were also used to lend greater validity to this study. Findings revealed that CwDs can act as active social agents influencing their own education; developmental dispositions have a direct relationship on this influence. -

Vietnam: Torture, Arrests of Montagnard Christians Cambodia Slams the Door on New Asylum Seekers

Vietnam: Torture, Arrests of Montagnard Christians Cambodia Slams the Door on New Asylum Seekers A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper January 2005 I. Introduction ..........................................................................................................2 II. Recent Arrests and harassment ...........................................................................5 Arrests of Church Leaders and Suspected Dega Activists.................................. 6 Detention of Families of Refugees...................................................................... 7 Mistreatment of Returnees from Cambodia ........................................................ 8 III. Torture and abuse in Detention and police custody.........................................13 Torture of Suspected Activists .......................................................................... 13 Mistreatment of Deportees from Cambodia...................................................... 15 Arrest, Beating, and Imprisonment of Guides for Asylum Seekers.................. 16 IV. The 2004 Easter Crackdown............................................................................18 V. Religious Persecution........................................................................................21 Pressure on Church Leaders.............................................................................. 21 VI. New Refugee Flow ..........................................................................................22 VII. Recommendations ..........................................................................................24 -

The Plight of the Montagnards,” Hearing Before the Committee of Foreign Relations United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, Second Session (Washington DC: U.S

Notes 1 Introduction and Afterword 1. Senator Jesse Helms, “The Plight of the Montagnards,” Hearing Before The Committee Of Foreign Relations United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, Second Session (Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, March 10, 1988), 1, http://frwebgate. access.gpo.gov/cg...senate_hearings&docid=f:47 64.wais, 10-5-99. 2. Ibid., 3. 3. Y’Hin Nie, in ibid., 24. 4. The word “Dega” is used by the refugees in both singular and plural constructions (e.g., “A Dega family arrived from Vietnam this week,” as well as “Many Dega gathered for church.”). 5. For a recent analysis of the historical emergence of names for popula- tion groups in the highlands of Southeast Asia, including the central highlands of Vietnam, see Keyes, “The Peoples of Asia,” 1163–1203. 6. There are no published studies of the Dega refugee community, but see: Cecily Cook, “The Montagnard-Dega Community of North Carolina” (University of North Carolina: MA Thesis in Folklore Studies, 1994); Cheyney Hales and Kay Reibold, Living in Exile, Raleigh (a film pro- duced by the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1994); and David L. Driscoll, “We Are the Dega: Ethnic Identification in a Refugee Community” (Wake Forest University: MA Thesis in Anthropology, 1994). Studies of the Hmong include: Robert Downing and D. Olney, eds., The Hmong in the West (Minneapolis: Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, 1982); Shelly R. Adler, “Ethnomedical Pathogenesis and Hmong Immigrants’ Sudden Nocturnal Deaths,” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 18 (1994): 23–59; Kathleen M. McInnis, Helen E. Petracchi, and Mel Morgenbesser, The Hmong in America: Providing Ethnic-Sensitive Health, Education, and Human Services (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1990); and Anne Fadiman, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998). -

2 Indigenous Peoples in Cambodia

UNITED NATIONS COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION (76TH SESSION 2010) Submitted by Indigenous People NGO Network (IPNN) Coordinated by NGO Forum on Cambodia In cooperation with Asian Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) February 2010 UNITED NATIONS COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION (76TH SESSION 2010) THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN CAMBODIA Submitted by Indigenous People NGO Network (IPNN) Coordinated by NGO Forum on Cambodia In cooperation with Asian Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................2 2 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN CAMBODIA ..........................................................................................2 3 OVERALL LEGAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................................................3 4 EDUCATION ...........................................................................................................................................4 5 NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT...........................................................................................4 5.1 Forest Issues ...........................................................................................................................................5ry 5.2 Protected Areas..........................................................................................................................................6 5.3 LAND...............................................................................................................................................................7