Behind the Lens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction: Regional Report

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES/ETHNIC MINORITIES AND POVERTY REDUCTION REGIONAL REPORT Roger Plant Environment and Social Safeguard Division Regional and Sustainable Development Department Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines June 2002 © Asian Development Bank 2002 All rights reserved Published June 2002 The views and interpretations in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asian Development Bank. ISBN No. 971-561-438-8 Publication Stock No. 030702 Published by the Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980, Manila, Philippines FOREWORD his publication was prepared in conjunction with an Asian Development Bank (ADB) regional technical assistance (RETA) project on Capacity Building for Indigenous Peoples/ T Ethnic Minority Issues and Poverty Reduction (RETA 5953), covering four developing member countries (DMCs) in the region, namely, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Viet Nam. The project is aimed at strengthening national capacities to combat poverty and at improving the quality of ADB’s interventions as they affect indigenous peoples. The project was coordinated and supervised by Dr. Indira Simbolon, Social Development Specialist and Focal Point for Indigenous Peoples, ADB. The project was undertaken by a team headed by the author, Mr. Roger Plant, and composed of consultants from the four participating DMCs. Provincial and national workshops, as well as extensive fieldwork and consultations with high-level government representatives, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), and indigenous peoples themselves, provided the basis for poverty assessment as well as an examination of the law and policy framework and other issues relating to indigenous peoples. Country reports containing the principal findings of the project were presented at a regional workshop held in Manila on 25–26 October 2001, which was attended by representatives from the four participating DMCs, NGOs, ADB, and other finance institutions. -

20201103 Réouverture Lieux Biens Culturels

Communiqué Plus que jamais, les biens culturels sont des biens essentiels ! Comment les magasins culturels se sont-ils retrouvés dans la catégorie des « commerces non essentiels » ? Comment expliquer à nos concitoyens que le seul rayon fermé de leur supermarché habituel est le rayon culture ? Comment peut-on les priver, alors qu’ils sont à nouveau confinés chez eux, de l’accès aux biens culturels ? Comment a-t-on pu en arriver là ? Parce qu’il est indispensable de préserver les derniers loisirs culturels possibles en période de confinement, après la fermeture des salles de spectacle, des théâtres, des cinémas et des musées. Parce que la fermeture des magasins culturels risque de fragiliser un peu plus ces acteurs courageux qui restent convaincus que l’envie de découvrir une œuvre et de la partager avec ceux que l’on aime est une expérience unique à vivre. Parce qu’il est insensé de dresser les uns contre les autres les commerces indépendants, les grandes surfaces et le commerce en ligne alors que toute l’économie est déjà soumise à de fortes pressions. Parce que la fermeture des rayons culture de la grande distribution est une aberration qu’aucun principe juridique ou économique ne peut justifier, et ce d’autant plus qu’ils étaient restés ouverts durant toute la durée du premier confinement. Parce que tous ces acteurs sont responsables et sauront mettre en place les mesures sanitaires renforcées propres à assurer la sécurité sanitaire de leurs clients, comme tous les autres commerces dits « essentiels ». Parce qu’en tout état de cause, la cohérence doit primer et qu’il n’apparaît pas plus dangereux de se rendre chez son disquaire ou son libraire que dans une boucherie-charcuterie, de même que le virus ne circule pas plus activement dans les rayons aujourd’hui fermés de la grande distribution que dans les autres. -

The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive A Change is Gonna Come: The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies And Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Laws in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kurt Dahl © Copyright Kurt Dahl, September 2009. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan 15 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ABSTRACT The purpose of my research is to examine the music industry from both the perspective of a musician and a lawyer, and draw real conclusions regarding where the music industry is heading in the 21st century. -

The Silent Emergency

Master Thesis The silent emergency: ”You are what you eat!‘ (The perceptions of Tampuan mothers about a healthy well nourished body in relationship to their daily food patterns and food habits) Ratanakiri province Cambodia Margriet G. Muurling-Wilbrink Amsterdam Master‘s in Medical Anthropology Faculty of Social & Behavioural Sciences Universiteit van Amsterdam Supervisor: Pieter Streefland, Ph.D. Barneveld 2005 The silent emergency: ”You are what you eat!‘ 1 Preface ”I am old, my skin is dark because of the sun, my face is wrinkled and I am tired of my life. You are young, beautiful and fat, but I am old, ugly and skinny! What can I do, all the days of my life are the same and I do not have good food to eat like others, like Khmer people or Lao, or ”Barang‘ (literally French man, but used as a word for every foreigner), I am just Tampuan. I am small and our people will get smaller and smaller until we will disappear. Before we were happy to be smaller, because it was easier to climb into the tree to get the fruit from the tree, but nowadays we feel ourselves as very small people. We can not read and write and we do not have the alphabet, because it got eaten by the dog and we lost it. What should we do?‘ ”We do not have the energy and we don‘t have the power to change our lives. Other people are better than us. My husband is still alive, he is working in the field and he is a good husband, because he works hard on the field. -

Yael Naim Yael Naim Mp3, Flac, Wma

Yael Naim Yael Naim mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Folk, World, & Country Album: Yael Naim Country: France Released: 2007 Style: Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1167 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1217 mb WMA version RAR size: 1339 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 240 Other Formats: VOC DTS AC3 WMA AAC MP4 TTA Tracklist Hide Credits Paris 1 Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar – Noam BurgAcoustic Guitar, Melodica, Piano – Yael 3:07 NaimDrums – Xavier TriboletProgrammed By – David Donatien Too Long 2 Acoustic Guitar, Synthesizer, Organ – Yael NaimOrgan, Bass, Drums, Percussion, 4:42 Synthesizer – David DonatienTrombone – Sebastien Llado New Soul 3 Acoustic Guitar, Piano, Synthesizer, Choir – Yael NaimBass, Electric Guitar – Laurent 3:45 DavidDrums, Percussion, Ukulele – David DonatienTrombone – Sebastien Llado Levater 4 Acoustic Guitar, Piano – Yael NaimCello – Yoed NirElectric Guitar, Organ, Drum 3:24 Programming, Udu – David DonatienViolin – Stanislas Steiner Shelcha Acoustic Guitar, Electric Piano [Rhodes], Piano, Choir – Yael NaimCello – Yoed NirDouble 5 4:38 Bass – Ilan AbouDrums – Xavier TriboletElectric Guitar, Percussion [With Water], Udu – David DonatienFeaturing – Kid With No EyesWritten-By [Additional] – Clément Verzi Lonely 6 4:06 Cello – Yoed NirPiano – Yael NaimWritten-By [Additional] – Anne Warin Far Far Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar, Piano, Electric Piano [Rhodes], Programmed By – Yael 7 4:20 NaimBass – Laurent DavidElectric Guitar – Julien FeltinKalimba, Percussion, Synthesizer – David Donatien Yashanti 8 Acoustic Guitar – Yael NaimBass – Laurent DavidCello – Yoed NirDrums – Xavier 3:53 TriboletElectric Guitar – Noam BurgGuitar – Julien Feltin 7 Babooker 9 3:33 Acoustic Guitar – Yael NaimPercussion – David Donatien Lachlom 10 Acoustic Guitar, Organ, Bells, Choir – Yael NaimCello – Jean-Philippe Audin, Yoed 4:22 NirElectric Guitar – Julien FeltinTrombone, Violin – Fanny Rome Toxic Double Bass – Ilan AbouGuitar [Weissenborn] – Alexandre KinnLyrics By – C. -

Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: Phd

Access to Electronic Thesis Author: Lonán Ó Briain Thesis title: Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: PhD This electronic thesis is protected by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No reproduction is permitted without consent of the author. It is also protected by the Creative Commons Licence allowing Attributions-Non-commercial-No derivatives. If this electronic thesis has been edited by the author it will be indicated as such on the title page and in the text. Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain May 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music University of Sheffield © 2012 Lonán Ó Briain All Rights Reserved Abstract Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain While previous studies of Hmong music in Vietnam have focused solely on traditional music, this thesis aims to counteract those limited representations through an examination of multiple forms of music used by the Vietnamese-Hmong. My research shows that in contemporary Vietnam, the lives and musical activities of the Hmong are constantly changing, and their musical traditions are thoroughly integrated with and impacted by modernity. Presentational performances and high fidelity recordings are becoming more prominent in this cultural sphere, increasing numbers are turning to predominantly foreign- produced Hmong popular music, and elements of Hmong traditional music have been appropriated and reinvented as part of Vietnam’s national musical heritage and tourism industry. Depending on the context, these musics can be used to either support the political ideologies of the Party or enable individuals to resist them. -

Tampon Mag Avril 2021

‘ ‘ L’ERE duTampon #44 FLASHEZ-MOI | Magazine d’information bimestriel de la Commune du Tampon | n° 44 | Avril 2021 | L’ère du Tampon Sommaire avril 2021 BP 449 - 97430 Le Tampon VACCINATION Tél. 0262 57 86 86 / Fax. 0262 59 24 49 04. VACCINATION CONTRE LA COVID-19 Courriel : [email protected] www.letampon.fr Aggravation de la situation sanitaire à La Réunion Accélération de la vaccination Élargissement des publics prioritaires Directeur de publication André THIEN AH KOON Le mot du Maire 06. TALENTS TAMPONNAIS Rédaction Samia OMARJEE Les finalistes du concours de chant selon les catégories Chères Tamponnaises, Chers Tamponnais, Mise en page Isabelle TÉCHER Cela fait maintenant plus d’un an que nous devons vivre avec les mesures 08. ENVIRONNEMENT sanitaires. Plus d’un an que nous subissons le confinement de notre population, Photos la saturation de nos services de santé, les inquiétudes pour nos étudiants 4 Parc des Palmiers : avis favorable pour l'enquête publique SERVICE COMMUNICATION expatriés, nos enfants, l’isolement des personnes âgées, les interdictions de se regrouper, la menace directe sur nos vies... Illustrations 10. CRISE SANITAIRE FREEPIK.COM La situation ne semble pas s'améliorer, notamment dans nos hôpitaux et pour nos personnels soignants auxquels j’apporte tout mon soutien. Mesures renforcées contre la Covid-19 Impression Nos commerçants et artisans, sont jugés “non-essentiels” alors que, bien au Ah-Sing contraire, ils ont un rôle crucial pour l’emploi, le lien social et notre vie de tous les jours. 11. AGENDA Dépôt Légal n° 24880 Les nouvelles mesures restrictives impactent à nouveau largement les ENVIRONNEMENT Programmation des mois d'avril et mai entreprises et conduiront inévitablement à une nouvelle baisse de leur activité Ville du Tampon et de leur chiffre d’affaires. -

Yael Naim & David Donatien

PRÉCÉDENTS © Zoriah LAURÉATS 2010 : Gotan Project 2009 : David Guetta et Frédéric Riesterer Guadalupe Pineda 2008 : Amancio Prada 2007 : Air 2006 : Nana Mouskouri YAEL NAIM & DAVID DONATIEN Ça débute comme un conte de fées : après 2 ans passés à peaufiner leur GRAND PRIX premier album, Yael et David voient en DU RÉPERTOIRE 2008 leur titre «New Soul» devenir le thème d’une SACEM campagne promotionnelle pour la firme Apple, et À L’eXPORT entrent dans le Top 10 des classements de vente américains, décrochant au passage la «Victoire 2008 de l’Album World de l’Année». Discographie séléctive She was a boy — Tôt ou Tard (2010) Depuis, nos héros se sont mis à «asseoir» leur succès et à en préparer d’autres, à leur Yael Naim rythme. David a présenté à Yael des collaborateurs de choix, tels Lionel et Stéphane Belmondo, — Tôt ou Tard (2007) In a man’s womb Thomas Bloch, Eric Legnini, Tété, et ainsi sont nés de nouveaux titres. — EMI (2001) Un beau challenge pour Yael qui, durant son enfance en Israël, s’est initiée au piano clas- sique, mais a aussi découvert la pop, le jazz, le folk, et créé le groupe The Anti Collision. C’est en 2000, qu’elle revient en France, pour un concert de charité, et signe chez EMI pour un premier album sorti en 2001, «In a man’s womb». Elle est aussi engagée par Elie Chouraqui pour «Les Dix Commandements» où elle chantera pendant 2 ans et demi. Elle enchaîne en 2004 avec «Spartacus le Gladiateur», de Maxime Le Forestier, mis en scène par le même Chouraqui. -

Photo by Chan Sokheng.

(Photo by Chan Sokheng.) Livelihoods in the Srepok River Basin in Cambodia: A Baseline Survey Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ii Acknowledgements iii Map of the Srepok River Basin iv Map of the Major Rivers of Cambodia v Executive Summary vi 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Methodology 1 1.2 Scope and limitations 3 2. The Srepok River and Tributaries 4 3. Protected Areas 7 4. Settlement and Ethnicity 8 5. Land and the Concept of Village 12 6. Water Regime 14 7. Transport 17 8. Livelihoods 19 8.1 Lowland (wet) rice cultivation 19 8.2 Other cultivation of crops 22 8.3 Animal raising 25 8.4 Fishing 27 8.5 Wildlife collection 42 8.6 Collection of forest products 43 8.7 Mining 47 8.8 Tourism 49 8.9 Labor 49 8.10 Water supply 50 8.11 Health 51 9. Implications for Development Practitioners and Directions for Future Research 52 Annex 1. Survey Villages and Ethnicity 55 Annex 2. Data Collection Guides Used During Fieldwork 56 Annex 3. Maximum Sizes (kg) of Selected Fish Species Encountered in Past Two Years 70 References 71 i Livelihoods in the Srepok River Basin in Cambodia: A Baseline Survey List of Figures and Tables Figure 1: Map of the Srepok basin in Cambodia and target villages 2 Figure 2: Rapids on the upper Srepok 4 Figure 3: Water levels in the Srepok River 4 Figure 4: The Srepok River, main tributaries, and deep-water pools on the Srepok 17 Figure 5: Protected areas in the Srepok River basin 7 Figure 6: Ethnic groups in the Srepok River basin in Cambodia 11 Figure 7: Annual spirit ceremony in Chi Klap 12 Figure 8: Trends in flood levels 14 Figure 9: Existing and proposed hydropower dam sites within the basin 15 Figure 10: Road construction, Pu Chry Commune (Pech Roda District, Mondulkiri) 17 Figure 11: Dikes on tributaries of the Srepok 21 Figure 12. -

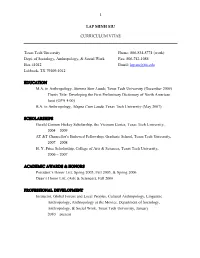

LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806

1 LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806-834-8774 (work) Dept. of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work Fax: 806-742-1088 Box 41012 Email: [email protected] Lubbock, TX 79409-1012 EDUCATION M.A. in Anthropology, Summa Sum Laude, Texas Tech University (December 2009) Thesis Title: Developing the First Preliminary Dictionary of North American Jarai (GPA 4.00) B.A. in Anthropology, Magna Cum Laude, Texas Tech University (May 2007) SCHOLARSHIPS Gerald Cannon Hickey Scholarship, the Vietnam Center, Texas Tech University, 2004 – 2009 AT &T Chancellor’s Endowed Fellowship, Graduate School, Texas Tech University, 2007 – 2008 H. Y. Price Scholarship, College of Arts & Sciences, Texas Tech University, 2006 – 2007 ACADEMIC AWARDS & HONORS President’s Honor List, Spring 2005, Fall 2005, & Spring 2006 Dean’s Honor List, (Arts & Sciences), Fall 2006 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Instructor, Global Forces and Local Peoples, Cultural Anthropology, Linguistic Anthropology, Anthropology at the Movies. Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January 2010 – present 2 Research Assistant/Language Consultant (Jarai). Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, June 2007 – December 2009 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. Jarai-Rhade Language Fonts Consultant. Linguist’s Software, Inc., July – September 2008 Assisted with the development and implementation of fonts for the Jarai and Rhade languages (www.linguistsoftware.com). Student/Language Consultant (Jarai). The Vietnam Center and Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January – May 2007 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. -

The Mosaert Philosophy

our story The creative label Mosaert - an anagram of Stromae - was founded in Brussels in 2009 by Paul Van Haver (better known as Stromae), together with his brother and artistic director Luc Junior Tam, to mark the launch of the singer’s first album, «Cheese». Since the beginning of his career, the author, composer and singer Stromae has wanted to produce his own music in order to maintain greater artistic independence. This means that his label will oversee everything, from production to artistic direction and from visuals to videos, not forgetting the staging of fashion shows and costumes. 2 The album «Cheese» was released in 2011. Aided by the concept of «Lessons from Stromae», and the various videos produced by Mosaert, such as the unforgettable «Alors on danse», it proved a great success and was a key feature of popular culture in 2009 and 2010. The single «Alors on danse» reached number 1 in 16 countries, selling more than 2 million copies; it was acclaimed by critics and the public alike for its individuality and its artistic coherence. 3 In 2014, Stromae released his second album, «Racine Carrée». The roaring success and amazing adventure represented by this second project can be summarised in a few figures: songs composed, written and performed for the most part by Stromae million copies sold worldwide videos released, with one billion Internet views live tour seen by more than 5 million people, with 209 performances in Europe, North America, South America and Africa 4 5 from music to fashion In 2012, the Mosaert team met Belgian stylist Coralie Barbier while working on the second Stromae album. -

Corkscrew Pointe

Corkscrew Pointe Artist Title Disc Number Track # 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10218 master 2 These Are The Days 10191 Master 1 Trouble Me 10191 Master 2 10Cc I'm Not In Love 10046 master 1 The Things We Do For Love 10227 Master 1 112 Dance With Me (Radio Version) 10120 master 112 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 10104 master 12 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1, 2, 3 Red Light 10124 Master 1910 2 Live Crew Me So Horny 10020 master 2 We Want Some P###Y 10136 Master 2 2 Pac Changes 10105 master 2 20 Fingers Short #### Man 10120 master 20 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 10131 master 3 Be Like That (Radio Version) 10210 master 3 Kryptonite May 06 2010 3 Loser 10118 master 3 311 All Mixed Up Mar 23 2010 311 Down 10209 Master 311 Love Song 10232 master 311 38 Special Caught Up In You 10203 38 Rockin' Into The Night 10132 Master 38 Teacher, Teacher 10130 Master 38 Wild-eyed Southern Boys 10140 Master 38 3Lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) (Radio 10127 Master 1 Version) 4 Non Blondes What's Up 10217 master 4 42Nd Street (Broadway Version) 42Nd Street 10227 Master 2 1 of 216 Corkscrew Pointe Artist Title Disc Number Track # 42Nd Street (Broadway Version) We're In The Money Mar 24 2010 14 50 Cent If I Can't 10104 master 50 In Da Club 10022 master 50 Just A Lil' Bit 10136 Master 50 P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 10092 master 50 Wanksta 10239 master 50 50 Cent and Mobb Deep Outta Control (Remix Version) 10195 master 50 50 Cent and Nate Dogg 21 Questions 10105 master 50 50 Cent and The Game How We Do (Radio Version) 10236 master 1 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 10105 master 69 98° Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 10016 master 4 I Do (Cherish You) 10128 Master 1 A Chorus Line What I Did For Love (Movie Version) 10094 master 2 A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) May 04 2010 1 A Perfect Circle Judith 10209 Master 312 The Hollow 10198 master 1 A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie 10213 master 1 A Taste Of Honey Sukiyaki 10096 master 1 A Teens Bouncing Off The Ceiling (Upside Down) 10016 master 5 A.B.