Photo by Chan Sokheng.

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction: Regional Report

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES/ETHNIC MINORITIES AND POVERTY REDUCTION REGIONAL REPORT Roger Plant Environment and Social Safeguard Division Regional and Sustainable Development Department Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines June 2002 © Asian Development Bank 2002 All rights reserved Published June 2002 The views and interpretations in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asian Development Bank. ISBN No. 971-561-438-8 Publication Stock No. 030702 Published by the Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980, Manila, Philippines FOREWORD his publication was prepared in conjunction with an Asian Development Bank (ADB) regional technical assistance (RETA) project on Capacity Building for Indigenous Peoples/ T Ethnic Minority Issues and Poverty Reduction (RETA 5953), covering four developing member countries (DMCs) in the region, namely, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Viet Nam. The project is aimed at strengthening national capacities to combat poverty and at improving the quality of ADB’s interventions as they affect indigenous peoples. The project was coordinated and supervised by Dr. Indira Simbolon, Social Development Specialist and Focal Point for Indigenous Peoples, ADB. The project was undertaken by a team headed by the author, Mr. Roger Plant, and composed of consultants from the four participating DMCs. Provincial and national workshops, as well as extensive fieldwork and consultations with high-level government representatives, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), and indigenous peoples themselves, provided the basis for poverty assessment as well as an examination of the law and policy framework and other issues relating to indigenous peoples. Country reports containing the principal findings of the project were presented at a regional workshop held in Manila on 25–26 October 2001, which was attended by representatives from the four participating DMCs, NGOs, ADB, and other finance institutions. -

The Silent Emergency

Master Thesis The silent emergency: ”You are what you eat!‘ (The perceptions of Tampuan mothers about a healthy well nourished body in relationship to their daily food patterns and food habits) Ratanakiri province Cambodia Margriet G. Muurling-Wilbrink Amsterdam Master‘s in Medical Anthropology Faculty of Social & Behavioural Sciences Universiteit van Amsterdam Supervisor: Pieter Streefland, Ph.D. Barneveld 2005 The silent emergency: ”You are what you eat!‘ 1 Preface ”I am old, my skin is dark because of the sun, my face is wrinkled and I am tired of my life. You are young, beautiful and fat, but I am old, ugly and skinny! What can I do, all the days of my life are the same and I do not have good food to eat like others, like Khmer people or Lao, or ”Barang‘ (literally French man, but used as a word for every foreigner), I am just Tampuan. I am small and our people will get smaller and smaller until we will disappear. Before we were happy to be smaller, because it was easier to climb into the tree to get the fruit from the tree, but nowadays we feel ourselves as very small people. We can not read and write and we do not have the alphabet, because it got eaten by the dog and we lost it. What should we do?‘ ”We do not have the energy and we don‘t have the power to change our lives. Other people are better than us. My husband is still alive, he is working in the field and he is a good husband, because he works hard on the field. -

Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: Phd

Access to Electronic Thesis Author: Lonán Ó Briain Thesis title: Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: PhD This electronic thesis is protected by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No reproduction is permitted without consent of the author. It is also protected by the Creative Commons Licence allowing Attributions-Non-commercial-No derivatives. If this electronic thesis has been edited by the author it will be indicated as such on the title page and in the text. Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain May 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music University of Sheffield © 2012 Lonán Ó Briain All Rights Reserved Abstract Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain While previous studies of Hmong music in Vietnam have focused solely on traditional music, this thesis aims to counteract those limited representations through an examination of multiple forms of music used by the Vietnamese-Hmong. My research shows that in contemporary Vietnam, the lives and musical activities of the Hmong are constantly changing, and their musical traditions are thoroughly integrated with and impacted by modernity. Presentational performances and high fidelity recordings are becoming more prominent in this cultural sphere, increasing numbers are turning to predominantly foreign- produced Hmong popular music, and elements of Hmong traditional music have been appropriated and reinvented as part of Vietnam’s national musical heritage and tourism industry. Depending on the context, these musics can be used to either support the political ideologies of the Party or enable individuals to resist them. -

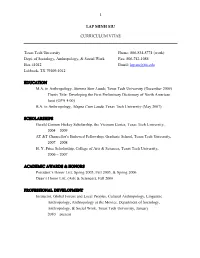

LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806

1 LAP MINH SIU CURRICULUM VITAE Texas Tech University Phone: 806-834-8774 (work) Dept. of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work Fax: 806-742-1088 Box 41012 Email: [email protected] Lubbock, TX 79409-1012 EDUCATION M.A. in Anthropology, Summa Sum Laude, Texas Tech University (December 2009) Thesis Title: Developing the First Preliminary Dictionary of North American Jarai (GPA 4.00) B.A. in Anthropology, Magna Cum Laude, Texas Tech University (May 2007) SCHOLARSHIPS Gerald Cannon Hickey Scholarship, the Vietnam Center, Texas Tech University, 2004 – 2009 AT &T Chancellor’s Endowed Fellowship, Graduate School, Texas Tech University, 2007 – 2008 H. Y. Price Scholarship, College of Arts & Sciences, Texas Tech University, 2006 – 2007 ACADEMIC AWARDS & HONORS President’s Honor List, Spring 2005, Fall 2005, & Spring 2006 Dean’s Honor List, (Arts & Sciences), Fall 2006 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Instructor, Global Forces and Local Peoples, Cultural Anthropology, Linguistic Anthropology, Anthropology at the Movies. Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January 2010 – present 2 Research Assistant/Language Consultant (Jarai). Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, June 2007 – December 2009 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. Jarai-Rhade Language Fonts Consultant. Linguist’s Software, Inc., July – September 2008 Assisted with the development and implementation of fonts for the Jarai and Rhade languages (www.linguistsoftware.com). Student/Language Consultant (Jarai). The Vietnam Center and Department of Sociology, Anthropology, & Social Work, Texas Tech University, January – May 2007 Collaborating on development of descriptive and pedagogical grammar of Jarai language – an indigenous language of Vietnam and spoken by over 3000 refugees in the United States and Canada. -

Behind the Lens

BEHIND THE LENS Synopsis On the banks of the Mekong, where access to education is a daily struggle, six children of different ages dream of a better future. Like the pieces of a puzzle, the paths taken by Prin, Myu Lat Awng, Phout, Pagna, Thookolo and Juliet fit together to tell the amazing story of WHEN I GROW UP. WHEN I GROW UP is first and foremost a story of a coming together. A coming together of a charity, Children of the Mekong, which has been helping to educate disadvantaged children since 1958; with a committed audio-visual production company, Aloest; with a film director, Jill Coulon, in love with Asia and with stories with a strong human interest; with a pair of world-famous musicians, Yaël Naïm and David Donatien. These multiple talents have collaborated to produce a wonderful piece of cinema designed to inform as many people as possible of the plight of these children and of the benefits of getting an education. Find out more at www.childrenofthemekong.org Credits: A film by Jill Coulon Produced by François-Hugues de Vaumas and Xavier de Lauzanne Director: Jill Coulon Assistant Director: Antoine Besson Editing: Daniel Darmon Audio mixing: Eric Rey Colour grading: Jean-Maxime Besset Music : Yaël Naïm and David Donatien Subtitles: Raphaële Sambardier Translation: Garvin Lambert Graphic design: Dare Pixel Executive Production Company: Aloest films Associate Production Company: Children of the Mekong INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR Jill Coulon A professional film director with a passion for all things Asia, Jill Coulon put her talent at the disposal of the six narrators of WHEN I GROW UP so they could tell their stories to an international audience. -

Vietnam: Torture, Arrests of Montagnard Christians Cambodia Slams the Door on New Asylum Seekers

Vietnam: Torture, Arrests of Montagnard Christians Cambodia Slams the Door on New Asylum Seekers A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper January 2005 I. Introduction ..........................................................................................................2 II. Recent Arrests and harassment ...........................................................................5 Arrests of Church Leaders and Suspected Dega Activists.................................. 6 Detention of Families of Refugees...................................................................... 7 Mistreatment of Returnees from Cambodia ........................................................ 8 III. Torture and abuse in Detention and police custody.........................................13 Torture of Suspected Activists .......................................................................... 13 Mistreatment of Deportees from Cambodia...................................................... 15 Arrest, Beating, and Imprisonment of Guides for Asylum Seekers.................. 16 IV. The 2004 Easter Crackdown............................................................................18 V. Religious Persecution........................................................................................21 Pressure on Church Leaders.............................................................................. 21 VI. New Refugee Flow ..........................................................................................22 VII. Recommendations ..........................................................................................24 -

The Plight of the Montagnards,” Hearing Before the Committee of Foreign Relations United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, Second Session (Washington DC: U.S

Notes 1 Introduction and Afterword 1. Senator Jesse Helms, “The Plight of the Montagnards,” Hearing Before The Committee Of Foreign Relations United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, Second Session (Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, March 10, 1988), 1, http://frwebgate. access.gpo.gov/cg...senate_hearings&docid=f:47 64.wais, 10-5-99. 2. Ibid., 3. 3. Y’Hin Nie, in ibid., 24. 4. The word “Dega” is used by the refugees in both singular and plural constructions (e.g., “A Dega family arrived from Vietnam this week,” as well as “Many Dega gathered for church.”). 5. For a recent analysis of the historical emergence of names for popula- tion groups in the highlands of Southeast Asia, including the central highlands of Vietnam, see Keyes, “The Peoples of Asia,” 1163–1203. 6. There are no published studies of the Dega refugee community, but see: Cecily Cook, “The Montagnard-Dega Community of North Carolina” (University of North Carolina: MA Thesis in Folklore Studies, 1994); Cheyney Hales and Kay Reibold, Living in Exile, Raleigh (a film pro- duced by the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1994); and David L. Driscoll, “We Are the Dega: Ethnic Identification in a Refugee Community” (Wake Forest University: MA Thesis in Anthropology, 1994). Studies of the Hmong include: Robert Downing and D. Olney, eds., The Hmong in the West (Minneapolis: Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, 1982); Shelly R. Adler, “Ethnomedical Pathogenesis and Hmong Immigrants’ Sudden Nocturnal Deaths,” Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 18 (1994): 23–59; Kathleen M. McInnis, Helen E. Petracchi, and Mel Morgenbesser, The Hmong in America: Providing Ethnic-Sensitive Health, Education, and Human Services (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1990); and Anne Fadiman, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998). -

2 Indigenous Peoples in Cambodia

UNITED NATIONS COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION (76TH SESSION 2010) Submitted by Indigenous People NGO Network (IPNN) Coordinated by NGO Forum on Cambodia In cooperation with Asian Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) February 2010 UNITED NATIONS COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION (76TH SESSION 2010) THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN CAMBODIA Submitted by Indigenous People NGO Network (IPNN) Coordinated by NGO Forum on Cambodia In cooperation with Asian Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................2 2 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN CAMBODIA ..........................................................................................2 3 OVERALL LEGAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................................................3 4 EDUCATION ...........................................................................................................................................4 5 NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT...........................................................................................4 5.1 Forest Issues ...........................................................................................................................................5ry 5.2 Protected Areas..........................................................................................................................................6 5.3 LAND...............................................................................................................................................................7 -

Repression of Montagnards

REPRESSION OF MONTAGNARDS Conflicts over Land and Religion in Vietnam’s Central Highlands Human Rights Watch New York • Washington • London • Brussels Copyright © April 2002 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-272-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2002104126 Cover photo: Copyright © 2001 Human Rights Watch Jarai women watching police and soldiers who have entered Plei Lao village, Gia Lai province on March 10, 2001 to break up an all-night prayer meeting. In the confrontation that followed, security forces killed one villager and then burned down the village church. Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500, Washington, DC 20009 Tel: (202) 612-4321, Fax: (202) 612-4333, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the Human Rights Watch news e-mail list, send a blank e-mail message to [email protected]. Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. -

Vietnam: Indigenous Minority Groups in the Central Highlands

UNHCR Centre for Documentation and Research WRITENET Paper No. 05/2001 VIETNAM: INDIGENOUS MINORITY GROUPS IN THE CENTRAL HIGHLANDS By An Independent WriteNet Researcher January 2002 WriteNet is a Network of Researchers and Writers on Human Rights, Forced Migration, Ethnic and Political Conflict WriteNet is a Subsidiary of Practical Management (UK) E-mail: [email protected] THIS PAPER WAS PREPARED MAINLY ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THE PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT PURPORT TO BE, EITHER EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THE PAPER ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF WRITENET OR UNHCR. ISSN 1020-8429 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction........................................................................................1 2 Geography, Ethnography and History of the Central Highlands.1 2.1 Geography.................................................................................................1 2.2 Ethnography and Ethnic Classification .................................................3 2.3 Colonial History .......................................................................................6 3 FULRO and the Question of “Montagnard” Autonomy ...............7 3.1 Before 1975 ...............................................................................................7 3.2 After 1975..................................................................................................8 -

Sociolinguistic Survey of Jarai in Ratanakiri, Cambodia

Sociolinguistic survey of Jarai in Ratanakiri, Cambodia Eric Pawley Mee-Sun Pawley International Cooperation Cambodia November 2010 2007-02 Jarai Survey Report v1.2.odt Printed 9. Oct. 2013 i Abstract Eric Pawley [Phnom Penh, Cambodia] This paper presents the report of a sociolinguistic survey of the Jarai variety spoken in Ratanakiri province, Cambodia. Jarai is one of the major “Montagnard” groups of the Vietnamese southern highlands. While Jarai numbers in Cambodia are much smaller, it is still one of the largest highland minority groups. This paper investigates the dialects used among the Jarai speakers in Ratanakiri province, their abilities in Khmer, and their attitudes towards language development. The data indicates that a minority of Jarai can speak some Khmer, but very few can read or write in either Khmer or Jarai. Nearly everyone interviewed expressed interest in learning to read and write Jarai. While many prefer the Roman script used by Jarai in Vietnam over the creation of a new Khmer- based script, most said that they would still be interested in learning a new script if it were made. There are only minor dialect differences between Jarai in Cambodia, but much greater differences with some varieties of Jarai spoken in Vietnam. ii Table of Contents 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Geography.................................................................................................................................1 -

Repression of Montagnards

REPRESSION OF MONTAGNARDS Conflicts over Land and Religion in Vietnam‘s Central Highlands Human Rights Watch New York • Washington • London • Brussels Copyright © April 2002 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-272-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2002104126 Cover photo: Copyright © 2001 Human Rights Watch Jarai women watching police and soldiers who have entered Plei Lao village, Gia Lai province on March 10, 2001 to break up an all-night prayer meeting. In the confrontation that followed, security forces killed one villager and then burned down the village church. Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500, Washington, DC 20009 Tel: (202) 612-4321, Fax: (202) 612-4333, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail: [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the Human Rights Watch news e-mail list, send a blank e-mail message to [email protected]. Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice.