The Paradox of the Angled Bracket-Arm and the Unorthodox “Speech Patterns” of Shanxi Regional Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditions and Foreign Influences: Systems of Law in China and Japan

TRADITIONS AND FOREIGN INFLUENCES: SYSTEMS OF LAW IN CHINA AND JAPAN PERCY R. LUNEY, JR.* I INTRODUCTION By training, what I know about Chinese law comes from my study of the Japanese legal system. Japan imported several early Chinese legal codes in the seventh and eighth centuries and adapted this law to existing Japanese social and economic conditions. The Chinese Confucian philosophy and system of ethics was introduced to Japan in the fourteenth century. The Japanese and Chinese legal systems adopted Western-style legal codes to foster economic growth and international trade; and, more importantly, both have an underlying foundation of Confucian philosophy. As an outsider to the study of China, my views represent those of a comparativist commenting on his perceptions of foreign influences on the Chinese legal system. These perceptions are based on my readings about Chinese law, my professional study of Japanese law, and the presentation given by Professor Whitmore Gray ("The Soviet Background") at the 1987 Duke Conference on Chinese Civil Law. Legal reforms in China are generating much debate by Western legal scholars about the future of the Chinese legal system. After the fall of the Gang of Four, the new Chinese Government has sought to strengthen and to improve the stature of the legal system. The goal is a socialist legal system with Chinese characteristics.' The post-Mao leadership views the legal system as an essential element in the economic development process. 2 Chinese expectations are that a legal system can provide the societal stability necessary for economic Copyright © 1989 by Law and Contemporary Problems * Associate Professor, North Carolina Central University School of Law; Visiting Professor, Duke University School of Law. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: from Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace

EUGENE Y. WANG Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: From Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace Why the Flight-to-the-Moon The Bard’s one-time felicitous phrasing of a shrewd observation has by now fossilized into a commonplace: that one may “hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”1 Likewise deeply rooted in Chinese discourse, the same analogy has endured since antiquity.2 As a commonplace, it is true and does not merit renewed attention. When presented with a physical mirror from the past that does register its time, however, we realize that the mirroring or showing promised by such a wisdom is not something we can take for granted. The mirror does not show its time, at least not in a straightforward way. It in fact veils, disfi gures, and ultimately sublimates the historical reality it purports to refl ect. A case in point is the scene on an eighth-century Chinese mirror (fi g. 1). It shows, at the bottom, a dragon strutting or prancing over a pond. A pair of birds, each holding a knot of ribbon in its beak, fl ies toward a small sphere at the top. Inside the circle is a tree fl anked by a hare on the left and a toad on the right. So, what is the design all about? A quick iconographic exposition seems to be in order. To begin, the small sphere refers to the moon. -

The Case of Wooden Buddhist Temples*

ETHNOLOGY DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.2.142-148 A.Y. Mainicheva1, 2, V.V. Talapov2, and Zhang Guanying3 1Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pr. Akademika Lavrentieva 17, Novosibirsk, 630090, Russia E-mail: [email protected] 2Novosibirsk State University of Architecture, Design and Arts, Krasny pr. 38, Novosibirsk, 630099, Russia E-mail: [email protected] 3AVIC Forestry CO., LTD, International Business Div. 22F, No. 28 Changjiang Rd, YEDA, Yantai, Shandong, China E-mail: [email protected] Principles of the Information Modeling of Cultural Heritage Objects: The Case of Wooden Buddhist Temples* This article describes the principles and prospects of using the BIM (building information modeling) technology, which was for the fi rst time used to reconstruct wooden Buddhist temples, to assess cultural information relating to them, and to evaluate the impact of the environment and exploitation. Preserving and restoring such temples is diffi cult because their construction includes wooden brackets—dougong. The BIM technology and our own method based on treatises of old Chinese architecture have enabled us to generate an information model of the temple (a new means of information processing) and to test it for geometric consistency. To create a library of elements, the Autodesk Revit software was used. To test the effi ciency of the library we applied the information model to the Shengmudian temple in the Shanxi province. The adaptation of the dougong library elements to wooden Buddhist temples provides the possibility for applying such technologies to generate a unifi ed system regardless of the software. Keywords: Architectural monuments, information modeling, BIM, Buddhist temples, dougong. -

Temple Architecture of Liao & Jin Dynasty

Recent Researches in Energy, Environment and Landscape Architecture Temple Architecture of Liao&Jin dynasty(916-1234A.D) in Datong JI JIANLE, CHENRONG College of Landscape Architecture Nanjing Forestry University 159 Longpan Road, 210037, Nanjing CHINA [email protected] http://yuanlin.njfu.edu.cn Abstract:Datong was the auxiliary capital of Liao and Jin Dynasties, it was also the Buddhist center of northern china at that time. A lot of Buddhist buildings were carefully preserved there. Most people don’t know that the architecture of the same time, such as Song, Liao and Jin Dynasties are followed Tang Dynasty but the same time they are different from each other. After doing the research about the Buddhist buildings in Datong, it was known that the architecture style of the dynasties of the same time such as Song , Liao and Jin was followed Tang Dynasty. But what is the difference from them? Through research these Buddhist buildings, we can conclude that people in Liao and Jin periods followed the architectural style of Tang Dynasty -- roof gentle gradient, eaves overhangs deeply, large Dougong, thick columns, the appearance of the building is simple, forceful and effective, unlike the building of Song , soft and beautiful. However, the building of Liao Dynasty developed their own characteristics, the appearance and use of oblique Dougong. Key Words: Datong,Liao and Jin Dynasties,Buddhism,architectural styles,Dougong,roof,decline of the columns during the end of Tang Dynasty and Wudai Dynasty 1 The Buddhist buildings during Liao until the beginning of Khitan Dynasty . Datong was in the Yanyun sixteen states, which later occupied by and Jin periods in Datong area Khitan in the times of Houjin Dynasty. -

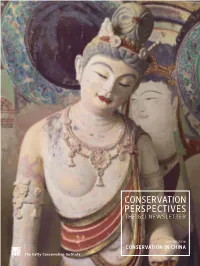

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Mothers' Ideas About Home-Based English Teaching and Learning For

Mothers’ Ideas about Home-Based English Teaching and Learning for Children Prior to School Age: A Study in Tainan, Taiwan Yi-Chen (Dora) Lan BA (National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan), MA (Central Missouri State University, USA) Institute of Early Childhood Faculty of Human Sciences Macquarie University This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2013 Table of Contents Title page Table of Contents i List of Tables v List of Appendices vi Abstract vii Statement of Candidate vii Acknowledgments ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 Aims of the Study/ Research Questions 7 Thesis Outline 8 Thesis by Publication Format 10 Chapter Two: Literature Review 13 Chinese Cultural Traditions 13 Recent Changes in the Taiwanese Political and Social Context 14 Factors Influencing Policy about English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in Early Childhood 16 The Ministry of Education (MOE) versus “English Fever” 20 Taiwanese Parents’ Attitudes towards Their Children’s Education 21 Taiwanese Parents’ Attitudes towards Early Introduction of EFL 22 Research on Appropriate Pedagogies for Young Children’s English as a Foreign Language Learning (EFLL) 23 Parents’ Beliefs, Ideas and Practices 25 The Importance of Mothers’ Educational Level and Its Relationship with Other Sociodemographic Variables 28 Summary 29 i Chapter Three: Methodology 31 Rational for Mixed Method Research Design 31 Ethical Issues 37 Recruitment of Participants 37 Profile of Participants 39 Data Collection 41 Methods of Analysis 42 Reliability, Trustworthiness and Transparency -

Can the West Learn from the Rest?' the Chinese Legal Order's Hybrid

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Other Publications Faculty Scholarship 2009 Can the West Learn from the Rest?' The hineseC Legal Order's Hybrid Modernity Nicholas C. Howson University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/other/4 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/other Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Howson, Nicholas C. "'Can the West Learn from the Rest?' The hineC se Legal Order's Hybrid Modernity." Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 32, no. 2 (2009): 815-30. This Speech is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Other Publications by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Panel IV - "Can the West Learn from the Rest?" - The Chinese Legal Order's Hybrid Modernityt By NICHOLAS CALCINA HOWSON* I am asked to present on the "shortcomings of the Western model of legality based on a professionalized, individualistic and highly formalistic approach to justice" as a way to understanding if "the West can develop today a form of legality which is relational rather than based on litigation as a zero sum game, learning from face to face social organizations in which individuals understand the law" - presumably in the context of the imperial and modem Chinese legal systems which I know best as a scholar and have lived for many years as a resident of the modem identity of the center of the "Chinese world," the People's Republic of China ("PRC"). -

Dissertation Section 1

Elegies for Empire The Poetics of Memory in the Late Work of Du Fu (712-770) Gregory M. Patterson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 ! 2013 Gregory M. Patterson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Elegies for Empire: The Poetics of Memory in the Late Work of Du Fu (712-770) Gregory M. Patterson This dissertation explores highly influential constructions of the past at a key turning point in Chinese history by mapping out what I term a poetics of memory in the more than four hundred poems written by Du Fu !" (712-770) during his two-year stay in the remote town of Kuizhou (modern Fengjie County #$%). A survivor of the catastrophic An Lushan rebellion (756-763), which transformed Tang Dynasty (618-906) politics and culture, Du Fu was among the first to write in the twilight of the Chinese medieval period. His most prescient anticipation of mid-Tang concerns was his restless preoccupation with memory and its mediations, which drove his prolific output in Kuizhou. For Du Fu, memory held the promise of salvaging and creatively reimagining personal, social, and cultural identities under conditions of displacement and sweeping social change. The poetics of his late work is characterized by an acute attentiveness to the material supports—monuments, rituals, images, and texts—that enabled and structured connections to the past. The organization of the study attempts to capture the range of Du Fu’s engagement with memory’s frameworks and media. It begins by examining commemorative poems that read Kuizhou’s historical memory in local landmarks, decoding and rhetorically emulating great deeds of classical exemplars. -

Ecaade 2021 Towards a New, Configurable Architecture, Volume 2

eCAADe 2021 Towards a New, Configurable Architecture Volume 2 Editors Vesna Stojaković, Bojan Tepavčević, University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Technical Sciences 1st Edition, September 2021 Towards a New, Configurable Architecture - Proceedings of the 39th International Hybrid Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Novi Sad, Serbia, 8-10th September 2021, Volume 2. Edited by Vesna Stojaković and Bojan Tepavčević. Brussels: Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Belgium / Novi Sad: Digital Design Center, University of Novi Sad. Legal Depot D/2021/14982/02 ISBN 978-94-91207-23-5 (volume 2), Publisher eCAADe (Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe) ISBN 978-86-6022-359-5 (volume 2), Publisher FTN (Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Serbia) ISSN 2684-1843 Cover Design Vesna Stojaković Printed by: GRID, Faculty of Technical Sciences All rights reserved. Nothing from this publication may be produced, stored in computerised system or published in any form or in any manner, including electronic, mechanical, reprographic or photographic, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authors are responsible for all pictures, contents and copyright-related issues in their own paper(s). ii | eCAADe 39 - Volume 2 eCAADe 2021 Towards a New, Configurable Architecture Volume 2 Proceedings The 39th Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe Hybrid Conference 8th-10th September -

The Spreading of Christianity and the Introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949)

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Programa de doctorado en Concervación y Restauración del Patrimonio Architectónico The Spreading of Christianity and the introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949) Christian churches and traditional Chinese architecture Author: Shan HUANG (Architect) Director: Antonio LOPERA (Doctor, Arquitecto) 2014 Tribunal nombrado por el Magfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 20 . Presidente: Vocal: Vocal: Vocal: Secretario: Suplente: Suplente: Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día de de 20 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Calificación:………………………………. El PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Index Index Abstract Resumen Introduction General Background........................................................................................... 1 A) Definition of the Concepts ................................................................ 3 B) Research Background........................................................................ 4 C) Significance and Objects of the Study .......................................... 6 D) Research Methodology ...................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Chinese traditional architecture 1.1 The concept of traditional Chinese architecture ......................... 13 1.2 Main characteristics of the traditional Chinese architecture .... 14 1.2.1 Wood was used as the main construction materials ........ 14 1.2.2 -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115