Hazara Report 2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Disarmament and Rearmament in Afghanistan

[PEACEW RKS [ THE POLITICS OF DISARMAMENT AND REARMAMENT IN AFGHANISTAN Deedee Derksen ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines why internationally funded programs to disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate militias since 2001 have not made Afghanistan more secure and why its society has instead become more militarized. Supported by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) as part of its broader program of study on the intersection of political, economic, and conflict dynamics in Afghanistan, the report is based on some 250 interviews with Afghan and Western officials, tribal leaders, villagers, Afghan National Security Force and militia commanders, and insurgent commanders and fighters, conducted primarily between 2011 and 2014. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Deedee Derksen has conducted research into Afghan militias since 2006. A former correspondent for the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant, she has since 2011 pursued a PhD on the politics of disarmament and rearmament of militias at the War Studies Department of King’s College London. She is grateful to Patricia Gossman, Anatol Lieven, Mike Martin, Joanna Nathan, Scott Smith, and several anonymous reviewers for their comments and to everyone who agreed to be interviewed or helped in other ways. Cover photo: Former Taliban fighters line up to handover their rifles to the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan during a reintegration ceremony at the pro- vincial governor’s compound. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. j. g. Joe Painter/RELEASED). Defense video and imagery dis- tribution system. The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. -

People of Ghazni

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies [email protected] Updated: June 1, 2010 Province: Baghlan Governor: Munshi Abdul Majid Deputy Governor: Sheikh Baulat (Deceased as a result of February 2008 auto accident) Provincial Police Chief: Abdul Rahman Sayedkhali PRT Leadership: Hungary Population Estimate: 1 Urban: 146,000 Rural: 616,500 Area in Square Kilometers: 21,112 sq. km Capital: Puli Khumri Names of Districts: Kahmard, Tala Wa Barfak, Khinjan, Dushi, Dahana-i-Ghori, Puli Khumri, Andarab, Nahrin, Baghlan, Baghlani Jadid, Burka, Khost Wa Firing Composition of Ethnic Groups: Religious Tribal Groups: Population:2 Tajik: 52% Groups: Gilzhai Pashtun 20% Pashtun: 20% Sunni 85% Hazara: 15% Shi'a 15% Uzbek: 12% Tatar: 1% Income Generation Major: Minor: Agriculture Factory Work Animal Husbandry Private Business (Throughout Province) Manual Labor (In Pul-i-Khomri District) Crops/Farming/Livestock: Agriculture: Livestock: Major: Wheat, Rice Dairy and Beef Cows Secondary: Cotton, Potato, Fodder Sheep (wool production) Tertiary: Consumer Vegetables Poultry (in high elevation Household: Farm Forestry, Fruits areas) Literacy Rate Total:3 20% Number of Educational Schools: Colleges/Universities: 2 Institutions:4 Total: 330 Baghlan University-Departments of Primary: 70 Physics, Social Science and Literature Lower Secondary: 161 in Pul-e-Khumri. Departments of Higher Secondary: 77 Agriculture and Industry in Baghlan Islamic: 19 Teacher Training Center-located in Tech/Vocational: 2 Pul-e-Khumri University: 1 Number of Security January: 3 May: 0 September: 1 Incidents, 2007: 8 February: 0 June: 0 October: 0 March: 0 July: 0 November: 2 April: 2 August: 0 December: 0 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation:5 2006: 2,742 ha 2007: 671 ha NGOs Active in Province: UNHCR, FAO, WHO, IOM, UNOPS, UNICEF, ANBP, ACTED, AKF/AFDN, CONCERN, HALO TRUST, ICARDA, SCA, 1 Central Statistics Office Afghanistan, 2005-2006 Population Statistics, available from http://www.cso- af.net/cso/index.php?page=1&language=en (accessed May 7, 2008). -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Afganistanin Tilannekatsaus Toukokuussa 2017

MUISTIO MIGDno-2017-381 MMaatietopalvelu MIG-177191 12.512.5.2017 Julkinen AFGANISTANIN TILANNEKATSAUS TOUKOKUUSSA 2017 Tässä katsauksessa käsitellään Afganistanin turvallisuusolosuhteita ja siihen vaikuttavia merkittä- vimpiä tapahtumia ja turvallisuusvälikohtauksia, joita Afganistanissa on sattunut 12.5.2017 men- nessä. Katsaus päivittää maatietopalvelun aiempaa vastaavaa selvitystä (Afganistanin turvalli- suustilanne vuoden 2017 alussa, 17.1.2017). Katsauksessa on käytetty eri julkisten lähteiden, kuten YK-tahojen ja toimittajien, raportointia, joka on ollut Maahanmuuttoviraston saatavissa kat- sauksen kirjoittamisajankohtana. Afganistanin turvallisuustilanne on pysynyt epävakaana ja arvaamattomana. Konflikti on levinnyt aiempaa laajemmalle alueelle, mutta suurin osa taisteluista käydään kuitenkin edelleen maan etelä- ja itäosassa. Taliban-toiminta on lisääntynyt pohjoisessa, koillisessa ja lännessä. Idässä Nangarharin maakunnan ISIS-alueella sotilaalliset operaatiot ovat keväällä 2017 olleet erityisen intensiivisiä. ISIS-mielinen liikehdintä on lisääntynyt Afganistanin luoteisosassa. Siviiliuhrien mää- rä on 2017 alkuvuodesta ollut hienoisessa laskussa edellisvuoteen nähden ja konfliktin takia maan sisäisesti siirtymään joutuneiden määrä on toistaiseksi ollut selvästi edellisvuotta alhaisem- pi. Talibanin kevään taistelukampanja on alkanut toukokuussa voimakkaalla hyökkäyksellä Kun- duziin. Taisteluiden odotetaan kiihtyvän kesän ja syksyn aikana. Sisällys 1. Yleinen tilanne keväällä 2017 ................................................................................................ -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Commanders in Control Disarmament Demobilisation and Reintegration in Afghanistan under the Karzai administration Derksen, Linde Dorien Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Commanders in Control Disarmament Demobilisation and Reintegration in Afghanistan under the Karzai administration ABSTRACT Commanders in Control examines the four internationally-funded disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programmes in Afghanistan between 2003 and 2014. -

DOWNLOAD PDF File

Quote of the Day Fear www.outlookafghanistan.net I love the man that can smile in trouble, that can gather ” facebook.com/The.Daily.Outlook.Afghanistan strength from” distress, and grow brave by reflection. ‘Tis the business of little minds to shrink, but he whose Email: [email protected] heart is firm, and whose conscience approves his conduct, Phone: 0093 (799) 005019/777-005019 will pursue his principles unto death. Add: In front of Habibia High School, Thomas Paine District 3, Kabul, Afghanistan Volume No. 4494 Tuesday December 08, 2020 Qaws 18, 1399 www.outlookafghanistan.net Price: 20/-Afs Sweden 232 New Cases Assures of COVID-19, ‘Continued and 27 Deaths Long-Term Reported Support’ to Afghanistan KABUL - The Ministry of Public Health on Monday reported 232 new positive cases of COVID-19 out of 1,350 samples tested in the KABUL, Afghanistan – Chairman last 24 hours. of the High Council for National The Public Health Ministry also Reconciliation (HCNR) Abdullah reported 27 deaths and 202 recov- Abdullah on Sunday hosted the eries from COVID-19 in the same newly appointed Swedish Ambas- period. sador to Afghanistan Torkel Stiern- The new cases were reported in Ka- löf at Sapedar Palace, discussing Taliban Expect Release of Their bul (48), Herat (22), Kandahar (15), joint cooperation for betterment of Balkh (25), Nangarhar (10), Takhar the country. (9), Paktia (21), Baghlan (12), Kun- During the meeting, Abdullah Prisoners by Mid-December: Wilson duz (7), Parwan (15), Nimruz (3), congratulated Ambassador Stiern- KABUL - -

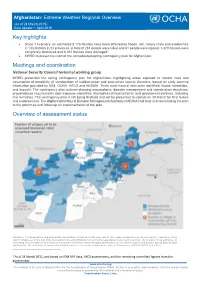

Key Highlights Meetings and Coordination Overview of Assessment Status

Afghanistan: Extreme Weather Regional Overview (as of 24 March 2015) Next update: 1 April 2015 Key highlights Since 1 February, an estimated 8,176 families have been affected by floods, rain, heavy snow and avalanches in 133 districts in 24 provinces. A total of 281 people were killed and 81 people were injured. 1,429 houses were completely destroyed and 6,357 houses were damaged1. MRRD to present to cabinet the consolidated spring contingency plan for Afghanistan. Meetings and coordination National Security Council technical working group MRRD presented the spring contingency plan for Afghanistan, highlighting areas exposed to hazard risks and assumption of possibility of combination of sudden-onset and slow-onset natural disasters, based on early warning information provided by IOM, OCHA, ARCS and ANDMA. Three main hazard risks were identified: floods; landslides, and drought. The contingency plan outlines planning assumptions, disaster management and coordination structures, preparedness requirements and response capacities (stockpiles) of humanitarian and government partners, including line ministries. The contingency plan is still being finalized and will be presented to cabinet on 30 March for final review and endorsement. The Afghanistan Natural Disaster Management Authority (ANDMA) will lead in disseminating the plan to the provinces and follow up on implementation of the plan. Overview of assessment status Number of villages yet to be assessed (based on initial unverified reports) Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map, and all other maps contained herein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

September 1, 2015

Page 4 September 1, 2015 (1) Pakistan Commisario, for his part, hailed Iran’s ernment and its international donors appreciation. People were encour- of commitments by the international equal rights. Women have the right to generous hosting of Afghan refugees to strengthen their support for the aged and their morale was uplifted community to Afghanistan, the com- submit documents for every vacancy Afghan government to come hard on for more than three decades as a shin- protection and promotion of human after you [Dostum] entered the prov- mitments by government will also through open competition. I assure Pakistan. President Ashraf Ghani ac- ing and outstanding example of as- rights in the country through contin- ince,” a tribal elder Sayed Ahmad told come under discussion. you no discrimination will be com- cused Pakistan of allowing militant sistance and support for the interna- ued emphasis on the Tokyo Mutual TOLOnews. “This meeting is very important to mitted against women, Inshah Allah,” hideouts on its soil tional community. Accountability Framework. Dostum said a few weeks back that he government which will discuss the the governor said. The government Javed Faisal, deputy spokesman for The UNHCR Executive Committee “However, there are indications the had donned his military uniform and commitments of the international blamed the lack of women employ- the CEO, told reporters efforts were head also urged Iran to actively par- Afghan government’s Realising Self- joined troops in the north in a bid to community to Afghanistan,” econom- ees in government departments on being made to defuse tension between ticipate in the Geneva meeting on Af- Reliance paper, presented by Presi- eliminate insurgents, motivate secu- ic analyst Azarakhsh Hafizi said. -

February 2012 | VOLUME - 5 ISSUE - 31

1 Monthly Risk Summary Monthly Risk Summary Afghanistan February 2012 | VOLUME - 5 ISSUE - 31 2-5 Executive Summary 53-71 Political 119 Afghanistan Map Situation SIMS Incident Health & Natural Security Advice & 6-28 Reporting 72-96 Hazards 120 Capabilities 29-36 Crime Topics 97-109 Business News Infrastructural & 37-52 Security News 110-117 Reconstruction Development February 2012 2 Monthly Risk Summary Executive Summary RISK SNAPSHOT Sims Incidents Criminial Activity Security Situation Political Situation Health & Natural Hazards Winter took its toll on the lives of Afghans as people perished in many parts of the country due to cold weather and avalanches. Heavy snowfall led to avalanch- es and blocked roads especially in Northern provinces in Afghanistan. Heavy rain- fall and floods added to the misery of Afghans. The heat of the Quran burning issue spread across the nation, making the lives of Afghan citizens even more miserable. Even though U.S authorities, including U.S President Barrack Obama, apologised on 21 February regarding the burning at a U.S military base of religious texts, which contained extremist contents, violent demonstrations marred the lives of many Afghans. That said, the NATO force pullout plan and handing over of the duties to Afghan forces was the main talking point of the month. Pullout Plans As part of the withdrawal plan, U.S Defense Secretary Leon Panetta on 1 Feb announced the intention to hand the lead combat role to Afghan Forces next year. This is a significant development for Afghanistan, considering the controversial U.S-led night raids which have caused much controversy. -

Your Ad Here Your Ad Here

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:X Issue No:99 Price: Afs.15 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes SATURDAY . NOVEMBER 07 . 2015 -Aqrab 16, 1394 HS Yo ur Yo ur ad ad he re he re AT Monitoring Desk incident is Maulvi Yusouf, who hana had been forced to marry wanted Rukhshana to marry his against her will and recently fled KABUL: The Governor of Ghor brother. However, the 19-year with another man. The couple was province, Seema Joyenda, said old girl refused to marry Maulvi caught after two days, and the that they have identified a number Yusouf s brother, thus he stoned Taliban militants stoned Rokhs- of people who were involved in her to death, she added. Accord- hana death for adultery. stoning a young woman to death. ing to Joyenda, Maulvi Yosuof This is worth mentioning that The Taliban militants under a was the main culprit in stoning so far there has been no arrests in decree by their kangaroo court Rukhshana. We have also identi- her stoning case, yet just only one stoned a teenager girl, identified fied other people involved in the name has been given out to media Rukhsana to death in western crime, but we cannot mention their as the main culprit, which in no Ghor province.Joyenda said that names, she said. way can be called a major devel- one of the people involved in the According to reports, Rukhs- opment towards justice. KABUL: Former vice president Mohammad Younus Qanuni has been appointed as the new chair- man of the High Peace Council (HPC), an official said. -

Taliban Widely Active Where Baghlan Coalminers Were Shot

2 Main News Page Taliban Suffer Heavy Casualties as 2 Major Taliban Widely Active where IED Factories Destroyed KABUL - The Taliban ties during the operations militants suffered heavy which were launched ten Baghlan Coalminers were Shot casualties during an op- days ago in Khashrud KABUL - Video footage obtained by still visible in the area. Shirzai, who also eration of the Afghan se- district. According to TOLOnews shows that Taliban mili- accompanied a military convoy into curity forces in western MoI, a compound used tants are extremely active in the Tala the district, said as the security forces Nimroz province of Af- by the shadow district Wa Barfak district in Baghlan where at moved into the area, they could see Tali- ghanistan, the Ministry of governor of the Taliban least eight coalminers were killed ear- ban strongholds getting stronger near Interior (MoI) said Thurs- was also destroyed dur- lier this month. the mountainous areas in Tala Wa Bar- day.According to a state ing the operations and The video shows how security forces fak. “We are in Anar Dara area. We con- ment by MoI, at least 80 at least 20 foreign insur- returned to Baghlan’s capital city, Pul- ducted the operation as per the order of Taliban insurgents were gents were killed. The e-Khumri, after reportedly failing to President [Ashraf Ghani]. We are here to killed and two large Im- anti-government armed arrest the perpetrators of the attack on arrest the two men who allergy gunned provised Explosive De- militant groups includ- coalminers due to the presence and ac- down the coalminers. -

1995 Comparative Survey

AFGHANISTAN DRUG CONTROL AND REHABILITATION PROGRAMME AFG/89/580 1995 COMPARATIVE SURVEY IIELMAND PROVINCE, AFGHANISTAN . Funded by United Nations International Drug Control Program1ne Implemented by United NationsACKU Office for Project Services Nove-mber 1995 Restricted circu1~tion for internal use in the UN syste1n only. " : ~ ; ,. ' AFGHANISTAl~" _ DRU~ CONTROL AND REHABILITATI()N PROGRAMME AFG/89/580 1995 COMPARATIVE SURVEY HELMAND PROVINCE, AFGHANISTAN ·, .· .. ' ' Funded by _ Unite(~ Nations International Drug Control Programnte . Implemented by '1Ji1itedACKU Nations Office for Project Services November 1995 Restricted circulation for internal use in the UN system only . .,· ( I ' Afghanistan Drug Control and Rehabilitation Programrne (ADCRP) Box 776, University Town · Peshawar · A project of the United Nations International Drug Control Programme (UNDCP) executed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) Published by the Afghanistan Drug Control and Rehabilitation Programme (ADCRP) Box 776, University Town Peshawar Available from the Afghanistan Drug Control and Rehabilitation Programme (ADCRP) Box 776, University Town Peshawar ACKU This survey and report do not necesSarily reflect the opinions, view points or policies of the United Nations International Drug Control Programme .or the United Nations office for Project Services . '\ J. TABLE OF CONTENTS . PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VI MAJOR FINDINGS IX INTRODUCTION . IntrOductory Statement · l su·rvey Objectives · Geographical ·Backgrou~d Agriculture and Irrigation 2., . Survey Area ~ METHODOLOGY 4 Background _ 4 Sources of Information 4 Data Collection Tools 4 Data Collection 5 Method of Data Analysis 6 Survey and Methodology Limitations '- 6 Training · 7 \ ' DEMOGRAPHY 9 ·Village and Family Size 9 · Repatriation . 10 Employment Opportunities 11 Influential Persons in the VillageACKU 12 AGRICULTURE AND IRRIGATION.