1 - Modifiability and Determinability, Loss of Aspects of Lexical (Concrete, Particular) Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Expressive Interjection Translation in Terms of Meanings

perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id ANALYSIS OF EXPRESSIVE INTERJECTION TRANSLATION IN TERMS OF MEANINGS, TECHNIQUES, AND QUALITY ASSESSMENTS IN “THE VERY BEST DONALD DUCK” BILINGUAL COMICS EDITION 17 THESIS Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Sarjana Degree at English Department of Faculty of Letters and Fine Arts University of Sebelas Maret By: LIA ADHEDIA C0305042 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LETTERS AND FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY OF SEBELAS MARET SURAKARTA 2012 THESIScommit APPROVAL to user i perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user ii perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id commit to user iii perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id PRONOUNCEMENT Name : Lia Adhedia NIM : C0305042 Stated whole-heartedly that this thesis entitled Analysis of Expressive Interjection Translation in Terms of Meanings, Techniques, and Quality Assessments in “The Very Best Donald Duck” bilingual comics edition 17 is originally made by the researcher. It is neither a plagiarism, nor made by others. The things related to other people’s works are written in quotation and included within bibliography. If it is then proved that the researcher cheats, the researcher is ready to take the responsibility. Surakarta, May 2012 The researcher Lia Adhedia C0305042 commit to user iv perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id MOTTOS “Allah does not change a people’s lot unless they change what their hearts is.” (Surah ar-Ra’d: 11) “So, verily, with every difficulty, there is relief.” (Surah Al Insyirah: 5) commit to user v perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to My beloved mother and father My beloved sister and brother commit to user vi perpustakaan.uns.ac.id digilib.uns.ac.id ACKNOWLEDGMENT Alhamdulillaahirabbil’aalamiin, all praises and thanks be to Allah, and peace be upon His chosen bondsmen and women. -

Introduction, Page 1

Introduction, page 1 Introduction This book is concerned with how structure, meaning and communicative function interact in human languages. Language is a system of communicative social action in which grammatical structures are employed to express meaning in context. While all languages can achieve the same basic communicative ends, different languages use different linguistic means to achieve them, and an important aspect of these differences concerns the divergent ways syntax, semantics and pragmatics interact across languages. For example, the noun phrase referring to the entity being talked about (the ‘topic’) may be signalled by its position in the clause, by its grammatical function, by its morphological case, or by a particle in different languages, and moreover in some languages this marking may have grammatical consequences and in other languages it may not. The framework in which this investigation is to be carried out is Role and Reference Grammar [RRG].1 RRG grew out of an attempt to answer two basic questions, which were originally posed during the mid-1970’s: (i) what would linguistic theory look like if it were based on the analysis of Lakhota, Tagalog and Dyirbal, rather than on the analysis of English?, and (ii) how can the interaction of syntax, semantics and pragmatics in different grammatical systems best be captured and explained? Accordingly, RRG has developed descriptive tools and theoretical principles which are designed to expose this interaction and offer explanations for it. It posits three main representations: (1) a representation of the syntactic structure of sentences, which corresponds to the actual structural form of utterances, (2) a semantic representation representing important facets of the meaning of linguistic expressions, and (3) a representation of the information (focus) structure of the utterance, which is related to its communicative function. -

Onomatopoeia, Gestures, Actions and Words: How Do Caregivers Use Multimodal Cues in Their Communication to Children?

Onomatopoeia, gestures, actions and words: How do caregivers use multimodal cues in their communication to children? Gabriella Vigliocco ([email protected]) Yasamin Motamedi, Margherita Murgiano, Elizabeth Wonnacott, Chloe Marshall, Iris Milan Maillo, Pamela Perniss Abstract However, in addition to being arbitrary, language presents also other types of form-meaning mapping characterized by Most research on how children learn the mapping between words and world has assumed that language is arbitrary, and a more transparent and motivated link (Dingemanse et al. has investigated language learning in contexts in which objects 2015). For example, iconicity, across languages, can be found referred to are present in the environment. Here, we report in the phonology of words, e.g. in onomatopoeia such analyses of a semi-naturalistic corpus of caregivers talking to as meow or drip. This expressive richness is particularly their 2-3 year-old. We focus on caregivers’ use of non-arbitrary prominent once we look at the multimodal communicative cues across different expressive channels: both iconic context in which language is learnt: prosodic (onomatopoeia and representational gestures) and indexical (points and actions with objects). We ask if these cues are used modulations (e.g. prolonging a vowel to indicate prolonged differently when talking about objects known or unknown to extension, loooong), iconic, representational gestures (e.g., the child, and when the referred objects are present or absent. tracing an up and down movement with the index finger We hypothesize that caregivers would use these cues more while talking about a bouncing object), points and hand often with objects novel to the child. -

TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional

Traditional Grammar Review Page 1 of 15 TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional grammar recognizes eight parts of speech: Part of Definition Example Speech noun A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. John bought the book. verb A verb is a word which expresses action or state of being. Ralph hit the ball hard. Janice is pretty. adjective An adjective describes or modifies a noun. The big, red barn burned down yesterday. adverb An adverb describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or He quickly left the another adverb. room. She fell down hard. pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. She picked someone up today conjunction A conjunction connects words or groups of words. Bob and Jerry are going. Either Sam or I will win. preposition A preposition is a word that introduces a phrase showing a The dog with the relation between the noun or pronoun in the phrase and shaggy coat some other word in the sentence. He went past the gate. He gave the book to her. interjection An interjection is a word that expresses strong feeling. Wow! Gee! Whew! (and other four letter words.) Traditional Grammar Review Page 2 of 15 II. Phrases A phrase is a group of related words that does not contain a subject and a verb in combination. Generally, a phrase is used in the sentence as a single part of speech. In this section we will be concerned with prepositional phrases, gerund phrases, participial phrases, and infinitive phrases. Prepositional Phrases The preposition is a single (usually small) word or a cluster of words that show relationship between the object of the preposition and some other word in the sentence. -

Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto De Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic

Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic To cite this version: Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic. Introduction: Complex Adpo- sitions and Complex Nominal Relators. Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Dejan Stosic, Elena Smirnova. Complex Adpositions in European Languages : A Micro-Typological Approach to Com- plex Nominal Relators, 65, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-30, 2020, Empirical Approaches to Language Typology, 978-3-11-068664-7. 10.1515/9783110686647-001. halshs-03087872 HAL Id: halshs-03087872 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03087872 Submitted on 24 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova & Dejan Stosic Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard CNRS, ENS & Paris Sorbonne Nouvelle; PSL Lattice laboratory, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 1 rue Maurice Arnoux, 92120 Montrouge, France [email protected] -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortti Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/ 521-0600 Order Number 9401286 The phonetics and phonology of Korean prosody Jun, Sun-Ah, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1993 300 N. Zeeb Rd. -

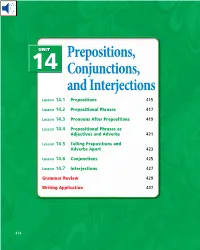

Prepositions, Conjunctions, and Interjections System of Classifying Books

UNIT Prepositions, 14 Conjunctions, and Interjections Lesson 14.1 Prepositions 415 Lesson 14.2 Prepositional Phrases 417 Lesson 14.3 Pronouns After Prepositions 419 Lesson 14.4 Prepositional Phrases as Adjectives and Adverbs 421 Lesson 14.5 Telling Prepositions and Adverbs Apart 423 Lesson 14.6 Conjunctions 425 Lesson 14.7 Interjections 427 Grammar Review 429 Writing Application 437 414 414_P2U14_888766.indd 414 3/18/08 12:21:23 PM 414-437 wc6 U14 829814 1/15/04 8:14 PM Page 415 14.114.1 Prepositions ■ A preposition is a word that relates a noun or a pronoun to some other word in a sentence. The dictionary on the desk was open. An almanac was under the dictionary. Meet me at three o’clock tomorrow. COMMONLY USED PREPOSITIONS aboard as despite near since about at down of through above before during off to across behind except on toward after below for onto under against beneath from opposite until Prepositions, Conjunctions, and Interjections along beside in out up amid between inside outside upon among beyond into over with around by like past without A preposition can consist of more than one word. I borrowed the almanac along with some other reference books. PREPOSITIONS OF MORE THAN ONE WORD according to along with because of in spite of on top of across from aside from in front of instead of out of Read each sentence below. Any word that fits in the blank is a preposition. Use the almanac that is the table. I took the atlas your room. 14.1 Prepositions 415 414-437 wc6 U14 829814 1/15/04 8:15 PM Page 416 Exercise 1 Identifying Prepositions Write each preposition from the following sentences. -

Inflection Rules for English to Marathi Translation

Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IJCSMC, Vol. 2, Issue. 4, April 2013, pg.7 – 18 RESEARCH ARTICLE Inflection Rules for English to Marathi Translation Charugatra Tidke 1, Shital Binayakya 2, Shivani Patil 3, Rekha Sugandhi 4 1,2,3,4 Computer Engineering Department, University Of Pune, MIT College of Engineering, Pune-38, India [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract— Machine Translation is one of the central areas of focus of Natural Language Processing where translation is done from Source Language to Target Language preserving the meaning of the sentence. Large amount of research is being done in this field. However, research in Machine Translation remains highly localized to the particular source and target languages due to the large variations in the syntactical construction of languages. Inflection is an important part to get the correct translation. Inflection is basically the adding of appropriate suffix to the word according to the sentence structure to obtain the meaningful form of the word. This paper presents the implementation of the Inflection for English to Marathi Translation. The inflection of Nouns, Pronouns, Verbs, Adjectives are done on the basis of the other words and their attributes in the sentence. This paper gives the rules for inflecting the above Parts-of-Speech. Key Terms: - Natural Language Processing; Machine Translation; Parsing; Marathi; Parts-Of-Speech; Inflection; Vibhakti; Prataya; Adpositions; Preposition; Postposition; Penn Tags I. INTRODUCTION Machine translation, an integral part of Natural Language Processing, is important for breaking the language barrier and facilitating the inter-lingual communication. -

Applying the Principle of Simplicity to the Preparation of Effective English Materials for Students in Iranian High Schools

APPLYING THE PRINCIPLE OF SIMPLICITY TO THE PREPARATION OF EFFECTIVE ENGLISH MATERIALS FOR STUDENTS IN IRANIAN HIGH SCHOOLS By MOHAMMAD ALI FARNIA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1980 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Professor Arthur J. Lewis, my advisor and chairperson of my dissertation committee, for his valuable guidance, not only in regard to this project, but during my past two years at the Uni- versity of Florida. I believe that without his help and extraordinary patience this project would never have been completed, I am also grateful to Professor Jayne C. Harder, my co-chairperson, for the invaluable guidance and assistance I received from her. I am greatly indebted to her for her keen and insightful comments, for her humane treatment, and, above all, for the confidence and motivation that she created in me in the course of writing this dissertation. I owe many thanks to the members of my doctoral committee. Pro- fessors Robert Wright, Vincent McGuire, and Eugene A. Todd, for their careful reading of this dissertation and constructive criticism. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my younger brother Aziz Farnia, whose financial support made my graduate studies in the United States possible. My personal appreciation goes to Miss Sofia Kohli ("Superfish") for typing the final version of this dissertation. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS , LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ^ ABSTRACT ^ii CHAPTER I I INTRODUCTION The Problem Statement 3 The Need for the Study 4 Problems of Iranian Students 7 Definition of Terms 11 Delimitations of the Study 17 Organization of the Dissertation 17 II REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 19 Learning Theories 19 Innateness Universal s in Language and Language Learning .. -

Syntactic Cues to the Noun and Verb Distinction in Mandarin Child

FLA0010.1177/0142723719845175First LanguageMa et al. 845175research-article2019 FIRST Article LANGUAGE First Language 1 –29 Syntactic cues to the © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: noun and verb distinction sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0142723719845175DOI: 10.1177/0142723719845175 in Mandarin child-directed journals.sagepub.com/home/fla speech Weiyi Ma University of Arkansas, USA Peng Zhou Tsinghua University, China Roberta Michnick Golinkoff University of Delaware, USA Joanne Lee Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada Kathy Hirsh-Pasek Temple University, USA Abstract The syntactic structure of sentences in which a new word appears may provide listeners with cues to that new word’s form class. In English, for example, a noun tends to follow a determiner (a/an/the), while a verb precedes the morphological inflection [ing]. The presence of these markers may assist children in identifying a word’s form class and thus glean some information about its meaning. This study examined whether Mandarin, a language that has a relatively impoverished morphosyntactic system, offers reliable morphosyntactic cues to the noun–verb distinction in child-directed speech (CDS). Using the CHILDES Beijing corpora, Study 1 found that Mandarin CDS has reliable morphosyntactic markers to the noun–verb distinction. Study 2 examined the Corresponding authors: Weiyi Ma, School of Human Environmental Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA. Email: [email protected] Peng Zhou, Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures, Tsinghua University, Beijing China. Email: [email protected] 2 First Language 00(0) relationship between mothers’ use of a set of early-acquired nouns and verbs in the Beijing corpora and the age of acquisition (AoA) of these words. -

SPELLING out P a UNIFIED SYNTAX of AFRIKAANS ADPOSITIONS and V-PARTICLES by Erin Pretorius Dissertation Presented for the Degree

SPELLING OUT P A UNIFIED SYNTAX OF AFRIKAANS ADPOSITIONS AND V-PARTICLES by Erin Pretorius Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisors Prof Theresa Biberauer (Stellenbosch University) Prof Norbert Corver (University of Utrecht) Co-supervisors Dr Johan Oosthuizen (Stellenbosch University) Dr Marjo van Koppen (University of Utrecht) December 2017 This dissertation was completed as part of a Joint Doctorate with the University of Utrecht. Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2017 Date The financial assistance of the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. The author also wishes to acknowledge the financial assistance provided by EUROSA of the European Union, and the Foundation Study Fund for South African Students of Zuid-Afrikahuis. Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za For Helgard, my best friend and unconquerable companion – all my favourite spaces have you in them; thanks for sharing them with me For Hester, who made it possible for me to do what I love For Theresa, who always takes the stairs Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Elements of language that are typically considered to have P (i.e. -

Adpositional Case

Adpositional Case S.A.M . Lestrade Adpositional Case Sander Lestrade PIONIER Project Case Cross-Linguistically Department of Linguistics Radboud University Nijmegen P.O. Box 9103 6500 HD Nijmegen The Netherlands www.ru.nl/pionier S.Lestrade@ let.ru.nl Adpositional Case M A Thesis Linguistics Department Radboud University Nijmegen May 2006 Sander Lestrade 0100854 First supervisor: Dr. Helen de Hoop Second supervisors: Dr. Ad Foolen and Dr. Joost Zwarts Acknowledgments I would like to thank Lotte Hogeweg and the members of the PIONIER project Case Cross-Linguistically for the nice cooperation and for providing a very stimulating working environment during the past year. Many thanks go to Geertje van Bergen for fruitful discussion and support during the process of writing. I would like to thank Ad Foolen and Joost Zwarts for their willingness to be my second supervisors and their useful comments on an earlier version; special thanks to Joost Zwarts for very useful and crucial discussion. Also, I gratefully acknowledge the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research (NWO) for financial support, grant 220-70-003, principal investigator Helen de Hoop (PIONIER-project “Case cross-linguistically”). Most of all, I would like to thank Helen de Hoop for her fantastic supervising without which I probably would not even have started, but certainly not have finished my thesis already. Moreover, I would like to thank her for the great opportunities she offered me to develop my skills in Linguistics. v Contents Acknowledgments v Contents vii Abbreviations