Evidence from the Diversification of American Labor Unions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in American Labor History: Course Module, Trade Union Women's Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 134 488 SO 009 696 AUTHOR Kopelov, Connie TITLE Women in American Labor History: Course Module, Trade Union Women's Studies. INSTITUTION State Univ. of New York, Ithaca. School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell Univ. PUB DATE Mar 76 VOTE 39p. AVAILABLE FROMNew York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University, 7 East 43rdStreet, New York, N.vis York 10017 ($2.00 paper cover) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage.' DESCRIPTORS Course Content; Economic Factors; Employees; Higher Education; i3i5tory Instruction; Labor Conditions; Labor Force; *Labor Unions; *Learning Modules; Political Influences; Social History; Socioeconomic Influences; *United States History; *Womers Studies; *Working Women ABSTRACT The role of working women in American laborhistory from colonial times to the present is the topicof this learning module. Intended predominantlyas a course outline, the module can also be used to supplement courses in social,labor, or American history. Information is presentedon economic and political influences, employment of women, immigration,vomen's efforts at labor organization, percentage of female workersat different periods, women in labor strikes, feminism,sex discrimination, maternity disabilitye and equality in the workplace. The chronological narrative focuses onwomen in the United States during the colonial period, the Revolutionary War period,the period from nationhood to the Civil War, from the CivilWar to 1900, from 1900 to World War I, from World War I to World War II,from World War II to 1960, and from 1960 through 1975. Each section isintroduced by a paragraph or short essay that highlights the majorevents of the period, followed by a series of topics whichare discussed and described by quotations, historical information,case studies, and accounts of relevant laws. -

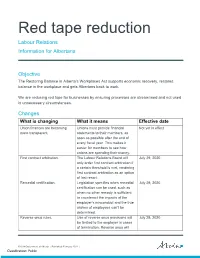

Red Tape Reduction: Labour Relations Information for Albertans-2021

Red tape reduction Labour Relations Information for Albertans Objective The Restoring Balance in Alberta’s Workplaces Act supports economic recovery, restores balance in the workplace and gets Albertans back to work. We are reducing red tape for businesses by ensuring processes are streamlined and not used in unnecessary circumstances. Changes What is changing What it means Effective date Union finances are becoming Unions must provide financial Not yet in effect more transparent. statements to their members, as soon as possible after the end of every fiscal year. This makes it easier for members to see how unions are spending their money. First contract arbitration. The Labour Relations Board will July 29, 2020 only order first contract arbitration if a certain threshold is met, rendering first contract arbitration as an option of last resort. Remedial certification. Legislation specifies when remedial July 29, 2020 certification can be used, such as when no other remedy is sufficient to counteract the impacts of the employer’s misconduct and the true wishes of employees can’t be determined. Reverse onus rules. Use of reverse onus provisions will July 29, 2020 be limited to the employer in cases of termination. Reverse onus will ©2018 Government of Alberta | Published: February 2021 | Classification: Public also apply to unions in cases where they have used coercion or intimidation in organizing campaigns. Early renewal of collective This will cut red tape for employers February 10, 2021 agreements. and unions by allowing early renewal of existing agreements, so long as employees consent. Consequences for prohibited Unions can be refused certification if July 29, 2020 practices conducted by union. -

Slu-SUP AID BEATS COMMIE DOCK GRAB Slu-SUP SEAMEN MASS Seafarers' Help Turns Tide SIU Strikes First Blow Against WSA in Longshore Raid; Rout NEW YORK

-we***) Official Organ of the Atlantic and Gulf District^ Seafarers International Union of North America Vol. VII. NEW YORK, N. Y„ FRIDAY. OCTOBER 26. 1945 No. 43 SlU-SUP AID BEATS COMMIE DOCK GRAB SlU-SUP SEAMEN MASS Seafarers' Help Turns Tide SIU Strikes First Blow Against WSA In Longshore Raid; Rout NEW YORK. Oct. 25—A mo- lion calculated to put the WSA Medical Division out of Commies With Counter-raily business was unanimously passed last night by the regti- United Action by the SIU-SUP, the ILA longshore lar fortnightly meeting of the men and the AFL Teamsters decisively defeated the attempt SIU in the Port of New York. of few communist-led "rank and file" longshoremen to The leadership was instructed swing the AFL longshoremen into the ranks of Harry to inform the necessary parties that henceforth no member of Bridges CIO outfit, and to take over control of the New York waterfront for the Com-^——— r the SIU would go to the WSA munist party. doctors for examination in this port. The communists leadership Speakers for the motion "called off the strike" when they pointed out that the WSA med were faced with the fact that the ics sought to perpetuate their Wearing their now famous white caps, members of the Sea dockworkers, had voted to go back pro-shipowner and anti-seaman farers Internationcd Union mass on New York's Broad Street to stop to work, determined to settle agency into the postwar pe communist hijacking of the AFL longshore union. They stopped it. their own affairs without com riod: agreements between the munist direction, leaving as the operators and the Union pro only "rank and filers" Joe Stack, vided for examination by the Harry Bridges, William Warren, company doctors, not the WSA; J list For The Rec ord and Salvatore Barone. -

A Program for Militant Trade Unionism

WHERE IS THE CIO GOING? By GEORGE MORRIS What happened to the c.I.O.? The question is heard on all sides. For some time it has been evident that the c.I.O. was being led away from the fighting, drive-ahead spirit that won it great sup port in earlier days. The sweeping organizing drives and pace setting economic gains that made it so attractive to the workers in the past are now giving way to internal strife, inter-union raid ing, Red-baiting, witch-hunting, stagnation and decline. The c.I.O.'s leaders were once the targets of union-haters. They were Red-baited. Today the union-haters sing hosannas to most of these very leaders beCause they themselves picked up Red-baiting and witch-hunting as weapons against progressives in the unions. The recent C.1.O. convention in Portland brought the long de veloping situation to a head. Differences carne out into the open and were fought out between the dominant Right and progressive Left. For the first time a c.I.O. convention faced two sets of resolutions. What's behind this · division in the C.1.O.? Who is responsible for it? How can the c.I.O. be brought back to the forward-looking path it followed in its earlier days? For an adequate answer to those questions we should first retrace the c.I.O.'s development both to the time of its birth-days when it was united and progressive -and further back, to the historic conditions that led to its rise. -

Seafarers Log 1962 Official Organ of the Seafarers International Union • Atlantic, Gulf, Lakes and Inland Waters District Afl-Cio

K : -_' • April SEAFARERS LOG 1962 OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE SEAFARERS INTERNATIONAL UNION • ATLANTIC, GULF, LAKES AND INLAND WATERS DISTRICT AFL-CIO Are Realistic Maritime Policies Ahead? President's House Group Message Report Raps Implies Lopsided |iV Need To Shipping Overhaul Subsidy 1936 Act Program An Infercoasfal Body. versions for intercoastal oper ation by SlU-contracted Sea-Land Service gets underway at Hoboken, -Story On Page 3 NJ, shipyard with arrival of specially-built midbody to fit between bow and stern of basic T-2 tankers cut apart for insertion of new midsection. This section is for the new SS San Juan due out by September, The other two ships will follow in December. (Story on iPage 4.) FRENCH, ITALIAN MARITIME UNIONS SIGN MTD PACTS Story On Page 3 NMU Seeks Scab Role In Robin Line -Story On Page 2 SlUNA TAXI UNION Laud SlU SirSk^ Aid Sailors and Firemen's Union New York representative iJfrffve AtfUa Johannes Nielsen presents a commemorative plaque to SIU WINS TOP GAINS president Paul Hall thanking the Union for its support during a strike last May. Looking on (left) are Thedy Nielsen, bosun on the Leader Maersk, one of the struck ships, and Michael Carlin, repre senting the Maritime Trades Department's International Division. Seafarers and members of other IN CHICAGO BEEF MTD unions assisted the Danish strikers in winning a wage beef. (Story on Page 2.) -Story On Page 5 "~.Tv"r-';is;:': T -JI ' Pace Two 6EAFJtttl^nil too April, I98t Advance Meeting Schedule Danes Laud For West Coast SIU Ports SIU headquarters has Issued an advance schedule through Sep tember for the monthly Informational meetings to be held in W^st Strike Aid Coast ports for the benefit of Seafarers shipping from Wilmington, San Francisco and Seattle or who are due to return from the Far East. -

2019 UNITE HERE Constitution

CONSTITUTION 2019 FOREWORD Organizing workers and reorganizing unions to act powerfully and effectively in the struggle to improve society must be the central task of every progressive trade union. For over a hundred years members of the unions that now comprise UNITE HERE have struggled against powerful forces and incredible odds to bring dignity and respect to the workplace. Whether our predecessors were cooks or tailors, seamstresses or room attendants, bartenders or mill hands, they had much in common. They often arrived in North America only a short time before they picked up their brooms or sat down at their sewing machines. Many of their forbearers came in the holds of slave ships. They often worked in family owned enterprises, bravely looking their employers directly in the eye as they asserted their rights and fought for their economic freedom. They labored long hours for low pay and made heroic sacrifices on the front lines of the labor movement of the twentieth century. In the twenty-first century, workers from across the globe continue to come to North America to work in our industries. Together with workers whose families have been here for generations, they confront the challenges of working for, bargaining with, and organizing global corporations. Workers today also confront a North American labor movement whose strength has been waning for decades. Our ability to achieve the gains we need--both on the job and in society more broadly--is in serious jeopardy. These realities are cause for grave concern not only for labor unions but also for all those who see unions, and the rights of workers, as an integral part of a democratic and equal society. -

Where Is the CIO Going?: a Program for Militant Trade Unionism

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1949 Where is the CIO going?: A program for militant trade unionism George Morris Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Morris, George, "Where is the CIO going?: A program for militant trade unionism" (1949). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 5. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/5 WHERE IS THE CIO GOING? By GEORGE MORRIS What happened to the c.I.O.? The question is heard on all sides. For some time it has been evident that the c.I.O. was being led away from the fighting, drive-ahead spirit that won it great sup port in earlier days. The sweeping organizing drives and pace setting economic gains that made it so attractive to the workers in the past are now giving way to internal strife, inter-union raid ing, Red-baiting, witch-hunting, stagnation and decline. The c.I.O.'s leaders were once the targets of union-haters. They were Red-baited. Today the union-haters sing hosannas to most of these very leaders beCause they themselves picked up Red-baiting and witch-hunting as weapons against progressives in the unions. The recent C.1.O. convention in Portland brought the long de veloping situation to a head. -

Legal/Legislative Developments Across Canada

FEATURED PRESENTATION— Legal/Legislative Developments Across Canada Lisa C. Chamzuk Hugh Wright Mark Zigler Partner CEO and Managing Partner Lawson Lundell LLP Partner Koskie Minsky LLP Vancouver, British McInnes Cooper Toronto, Ontario Columbia Halifax, Nova Scotia The opinions expressed in this presentation are those of the speaker. The International Foundation disclaims responsibility for views expressed and statements made by the program speakers. 400-1 Legal/Legislative Developments Across Canada Mark Zigler Partner Koskie Minsky LLP Toronto, Ontario The opinions expressed in this presentation are those of the speaker. The International Foundation disclaims responsibility for views expressed and statements made by the program speakers. 400-2 Part 1—Health and Welfare Trusts Folio—S2-F1-C1 • Updated November 28, 2015, but few changes • For the most part incorporates old Interpretation Bulletin IT-85-R2 but has specific problem areas 400-3 Problem 1—Allowing non-qualifying benefits such as—OTC medications, etc. • Resolved in part by November 2015 changes • Up to 10% of annual cost of fund benefits • Separate accounting for non eligible benefits? 400-4 Problem 2—Who is eligible for coverage? • Independent contractors? Owner-operators? • Partners and shareholders? • Non employees—beneficiaries, employed members, etc.? • Issue is still outstanding 400-5 Problem 3—“Surpluses” • What is difference between a temporary and permanent surplus • No reference to contingency reserves • May affect deductibility of employer contributions 400-6 Solutions: (1) Discussions with department of finance continue (2) Adopting new rules such as “ELHT” rules (3) Get advice on dealing with problematic issues 400-7 Possible union and trustee liability for disability fund deficit Watt v. -

Red Tape Reduction Labour Relations Information for Albertans

Red tape reduction Labour Relations Information for Albertans Objective The proposed Restoring Balance in Alberta’s Workplaces Act will support economic recovery, restore balance in the workplace and get Albertans back to work. We are reducing red tape for businesses by ensuring processes are streamlined and not used in unnecessary circumstances. Translation: The Restoring Balance in Alberta’s Workplaces Act will make it easier for bad employers to take advantage of workers who are desperate for work. We are creating more red tape for unions and making it more difficult for workers to unionize. Proposed Changes What is changing What it means What it REALLY means for workers Union finances are becoming Unions must provide financial Union members have more transparent. statements to their members, as soon always been able to get as possible after the end of every fiscal the financial statements from their unions. year. This makes it easier for members Changes like this are to see how unions are spending their often used to make it money. seem like unions are trying to hide their financials. ©2018 Government of Alberta | Published: July 2020 | First contract arbitration. Changes to the Code will ensure the This is an attempt to Board will only order first contract prevent first contractor arbitration if a certain threshold is met, arbitration which tends rendering first contract arbitration as to be successful and an option of last resort. gives workers more gains. Remedial certification. Legislation will specify when remedial This is another barrier to certification can be used, such as when prevent workers from no other remedy is sufficient to being able to unionize counteract the impacts of the when their employer employer’s misconduct and the true engages in illegal wishes of employees can’t be interference. -

Governance, Merit Pay, and Sexual Harassment. Part II Deals With

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 354 835 HE 026 255 AUTHOR Lowe, Ida B.; Johnson, Beth Hillman TITLE Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions. Bibliography No. 19. INSTITUTION City Univ. of New York, N.Y. Bernard Baruch Coll. National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions. REPORT NO ISSN-0738-1913 PUB DATE Jan 91 NOTE 91p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions, Baruch College, CUNY, 17 Lexington Ave., Box 322, New York, NY 10010 ($30). PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Collective Bargaining; College Faculty; *Employer Employee Relationship; Equal Opportunities (Jobs); *Faculty College Relationship; Governance; Higher Education; Labor Legislation; *Labor Relations; Nurses; *Professional Personnel; *Publications; Quality of Working Life; Retirement; Sexual Harassment; Teacher Salaries; Tenure ABSTRACT This bibliography, part of an annual accounting of the state-of-the-art in collective bargaining in higher education and the professions, lists research and writings published in 1990. The bibliography is divided into five parts. Part I is devoted to those publications concerned with college and university faculty; subjects include (among others) affirmative action, AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency devoted to those publications involving faculty and include the governance, merit pay, quality of worklife, retirement, salaries, tenure and promotion, and se.mal harassment. Part II deals with financial assistance that is part of the package, the procedures governance, merit pay, and sexual harassment. Part II deals with professions and professionals and includes publications covering the health care, sports, and nursing professions.