Where Is the CIO Going?: a Program for Militant Trade Unionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARTY WILL CEI2,BRTE SCHOOL's Hth ANNIVERSARY NINE ILR

November 4, 1949 Vol. II, No. 7 • FOR OUR INFORMATION F.O.I. appears bi-weekly from the Public Relations Office, Room 7, for the infor- mation of all faculty, staff and students of the New York State School orIndustrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University. A report of the Joint Legislative Committee on Industrial and Labor Conditions states, "The most satisfactory human relationships are the product, not of legal compulsion, but rather of voluntary determination among human beings to cooperate with one another." In the same spirit, F.O.I. is dedicated to our mutual understanding. EVERYONE INVITED TO ILR "OLD FASHIONED ELECTION PARTY" TUESDAY EVENING, NOV. 8; PARTY WILL CEI2,BRTE SCHOOLS hTH ANNIVERSARY Members of the faculty, staff and student body of the ILR School are invited to an Old Fashioned Election Night Party on Tuesday, November 8, in the Ivy Room of Willard Straight. The party is being given by the faculty, graduate students, and staff for undergraduate students of the ILR School. Husbands and wives are invited and all are urged to come and wear clothes suitable for square dancing. The fun will begin at 8:00 P.M. Refreshments, square dancing, election returns, a floor show, and other entertainment will be provided. Chairman of the Steering Committee for the party isLeane Eckert, Research Associate. NINE ILR STUDENTS ACTIVE ON GRIDIRON ILR School can be proud of its nine representatives on the football grid- iron this fall. Three ILR students are on the varsity team, three on the junior varsity, and three in the Big Red Band. -

Youngstown State University Oral History Program

YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM 1952 Youngstown Sheet & Tube Steel Strike Personal Experience O.H. 1218 RUSSELL L. THOMAS Interviewed by Andrew Russ on October 28, 1988 Russell Thomas resides in North Jackson, Ohio and was born on January 18, 1908 in East Palestine, Ohio. He attended high school in Coitsville, Ohio and eventually was employed for the United Steel Workers of America in the capacity of local union representative. Tn this capacity, he worked closely with the Youngstown's local steel workers' unions. It was from this position that he experienced the steel strike of 1952. Mr. Thomas, after relating his biography, went on to discuss the organization of the Youngstown contingent of the United Steel Workers of America. He went into depth into the union's genera- tion, it's struggle with management, and the rights it obtained for the average worker employed in the various steel mills of Youngstown. He recollected that the steel strike of 1952 was one that was different in the respect that President Truman had taken over the operation of the mills in order to prosecute the Korean War effort. He also discussed local labor politics as he had run for the posiUon of local union president. Although he was unsuccessful in this bid for office, his account of just how the local labor political game was played provided great insight into the labor movement's influence upon economic issues and public opinion. His interview was different in that it discussed not only particular issues that affected the average Youngstown worker employed in steel, but also broad political and economic ones that molded this period of American labor history. -

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O

Experiences of C.W. Editor in Steel Towns with C.I.O. Dorothy Day The Catholic Worker, August 1936, 1, 2. *Summary: Impressions from a fact-finding tour of Pennsylvania steel towns and interviews with such figures as Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; John L. Lewis, chairman of the CIO; Kathryn Lewis, his daughter; and John Brophy, Director of the CIO. For readers seeking background information on the steel/labor struggle, she recommends several books. Applauds church and government efforts to support labor in its struggle to organize and notes with satisfaction The CW ’s ability to transcend race and ethnic boundaries. Keywords: labor, unions, social teaching (DDLW #302).* A story like this is too big to compress in one column. Impressions crowded upon one over two weeks of constant observation are hard to put down on paper. There could be an interview with Bishop Boyle of Pittsburgh; with John L. Lewis, chairman of the Committee on Industrial Organization; with John Brophy, director of the committee; with Philip Murray, head of the Steel Workers’ Organization Committee (SWOC); with Pat Fagin, president of District No. 5 of the United Mine Workers; with the wives and mothers of steel workers; with Father Kazincy, who spoke from a wooden platform out in an open air mass meeting at Braddock last Sunday; with Smiley Chatak, the young organizer of the Allegheny Valley; with the Slovaks, the Croatians, the Syrians, the Italians and the Americans I have been seeing this past month–individuals among the 500,000 steel workers who have been unorganized, oppressed and enslaved for the last half century in the giant mills of the American Iron and Steel Institute. -

The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry Edward Himes III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Labor History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Himes, Henry Edward III, "Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3917. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3917 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bargaining for Security: The Rise of the Pension and Social Insurance Program of the United Steelworkers of America, 1941-1960 Henry E. Himes III Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Ken Fones-Wolf, PhD., Chair Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, PhD. -

The Winding Paths of Capital

giovanni arrighi THE WINDING PATHS OF CAPITAL Interview by David Harvey Could you tell us about your family background and your education? was born in Milan in 1937. On my mother’s side, my fam- ily background was bourgeois. My grandfather, the son of Swiss immigrants to Italy, had risen from the ranks of the labour aristocracy to establish his own factories in the early twentieth Icentury, manufacturing textile machinery and later, heating and air- conditioning equipment. My father was the son of a railway worker, born in Tuscany. He came to Milan and got a job in my maternal grand- father’s factory—in other words, he ended up marrying the boss’s daughter. There were tensions, which eventually resulted in my father setting up his own business, in competition with his father-in-law. Both shared anti-fascist sentiments, however, and that greatly influenced my early childhood, dominated as it was by the war: the Nazi occupation of Northern Italy after Rome’s surrender in 1943, the Resistance and the arrival of the Allied troops. My father died suddenly in a car accident, when I was 18. I decided to keep his company going, against my grandfather’s advice, and entered the Università Bocconi to study economics, hoping it would help me understand how to run the firm. The Economics Department was a neo- classical stronghold, untouched by Keynesianism of any kind, and no help at all with my father’s business. I finally realized I would have to close it down. I then spent two years on the shop-floor of one of my new left review 56 mar apr 2009 61 62 nlr 56 grandfather’s firms, collecting data on the organization of the production process. -

ABSTRACT CARVER, MARK DEAN. The

ABSTRACT CARVER, MARK DEAN. The Unionization of Erwin’s Mill: A History of TWUA Local 250, in Erwin, North Carolina: 1938-1952 (Under the direction of David Zonderman) The purpose of this study is to document the history of the Textile Workers union of America (TWUA), Local 250, in Erwin, North Carolina, from 1938-1952. Prior to unionization, Erwin’s workers suffered unfair labor practices including: heavy workloads, low wages, long hours, and the absence of grievance procedure. The unionization of Erwin’s workers provided a grievance procedure, fair workloads, higher wages, and better hours. TWUA Local 250 worked hard to represent its members and assure them a fair and just system. This thesis examines the first fifteen years of unionization and some of the problems that occurred in Erwin’s mill. These problems include anti-union sentiment, unfair company policies, an unnecessary strike, and a political power struggle within the national union. Through the examination of primary sources including company, union, government correspondences, newspaper articles, and personal interviews, it becomes evident that Erwin’s workers needed a union to ensure a fair and just system. A fair and just system would only be possible through better communication with the company, the national union, and the federal government. The company, national union, and government seemed to care very little for the desperate situations endured by Local 250 during these first fifteen years. This thesis shows the national union’s poor judgment, lack of leadership, and most of all, lack of compassion for Local 250. This study provides a view of the national union from the perspective of the local union. -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of Max Shachtman

The Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Max Shachtman Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: Max Shachtman Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Cousin John * Marty Dworkin * M.S. * Max Marsh * Max * Michaels * Pedro * S. * Max Schachtman * Sh * Maks Shakhtman * S-n * Tr * Trent * M.N. Trent Date and place of birth: September 10, 1904, Warsaw (Russia [Poland]) Date and place of death: November 4, 1972, Floral Park, NY (USA) Nationality: Russian, American Occupations, careers, etc.: Editor, writer, party leader Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - ca. 1948 Biographical sketch Max Shachtman was a renowned writer, editor, polemicist and agitator who, together with James P. Cannon and Martin Abern, in 1928/29 founded the Trotskyist movement in the United States and for some 12 years func tioned as one of its main leaders and chief theoreticians. He was a close collaborator of Leon Trotsky and translated some of his major works. Nicknamed Trotsky's commissar for foreign affairs, he held key positions in the leading bodies of Trotsky's international movement before, in 1940, he split from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), founded the Workers Party (WP) and in 1948 definitively dissociated from the Fourth International. Shachtman's name was closely webbed with the theory of bureaucratic collectivism and with what was described as Third Campism ('Neither Washington nor Moscow'). His thought had some lasting influence on a consider able number of contemporaneous intellectuals, writers, and socialist youth, both American and abroad. Once a key figure in the history and struggles of the American and international Trotskyist movement, Shachtman, from the late 1940s to his death in 1972, made a remarkable journey from the left margin of American society to the right, thus having been an inspirer of both Anti-Stalinist Marxists and of neo-conservative hard-liners. -

UCLA Ufahamu: a Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title OAU: Forces of Destabilization Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8mn839wp Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 13(1) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Okoth, P. Godfrey Publication Date 1983 DOI 10.5070/F7131017125 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California OAU: FORCES OF DESTABILIZATION* by P. Godfrey Okoth The Assembly shall be composed of the Heads of State and Government or their duly accredited representatives and it shall meet at least once a year. -Article 9 of the OAU Charter. Two-thirds of the total membership of the or ganization shall form a quorum at any meeting of the assembly. -Article 10 (iv) of the OAU Charter. This paper attempts to examine the historical role of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and the problems it is fa cing in an effort to fulfil .this role. The major contention being that the aims and objectives of the organization have changed over time, and a corresponding changes o·f pu·rpose and direction within the organization becomes thus urgent. This continental body -- the largest regional grouping in the world (in terms of constituent members), has been passing through difficult terrain. It must be said from the outset that we conceive the problems of the OAU as being imperialist and neo-colonialist forces at work to choke the progress of African unity. With their divisive and destabilizing plans for Africa, the western powers -- headed by the United States -- have for their own interests, insisted sn creating crises within the OAU. -

The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 11:01 Labour Journal of Canadian Labour Studies Le Travail Revue d’Études Ouvrières Canadiennes The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A. Zumoff Volume 85, printemps 2020 Résumé de l'article Dans les premières années de la Grande Dépression, le Parti socialiste URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070907ar américain a attiré des jeunes et des intellectuels de gauche en même temps DOI : https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2020.0006 qu’il était confronté au défi de se distinguer du Parti démocrate de Franklin D. Roosevelt. En 1936, alors que sa direction historique de droite (la «vieille Aller au sommaire du numéro garde») quittait le Parti socialiste américain et que bon nombre des membres les plus à gauche du Parti socialiste américain avaient décampé, le parti a perdu de sa vigueur. Cet article examine les luttes internes au sein du Partie Éditeur(s) socialiste américain entre la vieille garde et les groupements «militants» de gauche et analyse la réaction des groupes à gauche du Parti socialiste Canadian Committee on Labour History américain, en particulier le Parti communiste pro-Moscou et les partisans de Trotsky et Boukharine qui ont été organisés en deux petits groupes, le Parti ISSN communiste (opposition) et le Parti des travailleurs. 0700-3862 (imprimé) 1911-4842 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Zumoff, J. (2020). The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935. Labour / Le Travail, 85, 165–198. -

Krivine for President of France

Vol. 7, No. 19 0 1969 Intercontinental Press May 19, 1969 50c Krivine for President of France Grigorenko Arrested at Crimean Tartar Trial May Day in Britain Harvard Strike Report New Social Unrest in Santo Doming0 ALAIN KRIVINE: From Sante Prison to Elysee Palace? Ninth Congress of the Chinese CP -474- ALAIN KRIVINE FOR PRESIDENT OF FMCE The Ligue Communiste* CLCl an- "This candidacy ,I' Le Monde quoted nounced May 5 that it would enter Alain Bensaid as saying, "does not, therefore, Krivine as its candidate for president have an electoral objective. Its princi- of France in the June 1 elections. Kri- pal aim is to explain that nothing was vine was the main leader of the JCR and solved by the referendum, that nothing played a key role in the May-June up- will be solved following the 1st or the heaval. He was imprisoned in July for 15th of June. thirty-nine days and drafted into the army shortly after his release. At pres- "The economic and social problems ent Krivine is stationed at Verdun with remain; the financial apprehension, the the 150th Infantry Regiment. political instability, will not be healed for long by a victory for Pompidou. The The announcement of Krivine's can- solutions lie elsewhere: in a new mobili- didacy, which was featured on the front zation of the working class in the facto- page of the widely read Paris daily & ries and in the neighborhoods." Monde, came only hours after the Commu- nist party designated seventy-two-year- The army refused to allow Alain old Jacques Duclos as their standard Krivine to leave Verdun to attend the bearer. -

Women in American Labor History: Course Module, Trade Union Women's Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 134 488 SO 009 696 AUTHOR Kopelov, Connie TITLE Women in American Labor History: Course Module, Trade Union Women's Studies. INSTITUTION State Univ. of New York, Ithaca. School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell Univ. PUB DATE Mar 76 VOTE 39p. AVAILABLE FROMNew York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University, 7 East 43rdStreet, New York, N.vis York 10017 ($2.00 paper cover) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage.' DESCRIPTORS Course Content; Economic Factors; Employees; Higher Education; i3i5tory Instruction; Labor Conditions; Labor Force; *Labor Unions; *Learning Modules; Political Influences; Social History; Socioeconomic Influences; *United States History; *Womers Studies; *Working Women ABSTRACT The role of working women in American laborhistory from colonial times to the present is the topicof this learning module. Intended predominantlyas a course outline, the module can also be used to supplement courses in social,labor, or American history. Information is presentedon economic and political influences, employment of women, immigration,vomen's efforts at labor organization, percentage of female workersat different periods, women in labor strikes, feminism,sex discrimination, maternity disabilitye and equality in the workplace. The chronological narrative focuses onwomen in the United States during the colonial period, the Revolutionary War period,the period from nationhood to the Civil War, from the CivilWar to 1900, from 1900 to World War I, from World War I to World War II,from World War II to 1960, and from 1960 through 1975. Each section isintroduced by a paragraph or short essay that highlights the majorevents of the period, followed by a series of topics whichare discussed and described by quotations, historical information,case studies, and accounts of relevant laws. -

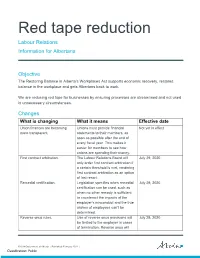

Red Tape Reduction: Labour Relations Information for Albertans-2021

Red tape reduction Labour Relations Information for Albertans Objective The Restoring Balance in Alberta’s Workplaces Act supports economic recovery, restores balance in the workplace and gets Albertans back to work. We are reducing red tape for businesses by ensuring processes are streamlined and not used in unnecessary circumstances. Changes What is changing What it means Effective date Union finances are becoming Unions must provide financial Not yet in effect more transparent. statements to their members, as soon as possible after the end of every fiscal year. This makes it easier for members to see how unions are spending their money. First contract arbitration. The Labour Relations Board will July 29, 2020 only order first contract arbitration if a certain threshold is met, rendering first contract arbitration as an option of last resort. Remedial certification. Legislation specifies when remedial July 29, 2020 certification can be used, such as when no other remedy is sufficient to counteract the impacts of the employer’s misconduct and the true wishes of employees can’t be determined. Reverse onus rules. Use of reverse onus provisions will July 29, 2020 be limited to the employer in cases of termination. Reverse onus will ©2018 Government of Alberta | Published: February 2021 | Classification: Public also apply to unions in cases where they have used coercion or intimidation in organizing campaigns. Early renewal of collective This will cut red tape for employers February 10, 2021 agreements. and unions by allowing early renewal of existing agreements, so long as employees consent. Consequences for prohibited Unions can be refused certification if July 29, 2020 practices conducted by union.